Travellers in Archives, Or the Possibilities of a Post-Post-Archival Historiography

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Focaal Forums - Virtual Issue

FOCAAL FORUMS - VIRTUAL ISSUE Managing Editor: Luisa Steur, University of Copenhagen Editors: Don Kalb, Central European University and Utrecht University Christopher Krupa, University of Toronto Mathijs Pelkmans, London School of Economics Oscar Salemink, University of Copenhagen Gavin Smith, University of Toronto Oane Visser, Institute of Social Studies, The Hague A regular feature of Focaal is its Forum section. The Forum features assertive, provocative, and idiosyncratic forms of writing and publishing that do not fit the usual format or style of a research-based article in a regular anthropology journal. Forum contributions can be stand-alone pieces or come in the form of theme-focused collection or discussion. Introducing: www.FocaalBlog.com, which aims to accelerate and intensify anthropological conversations beyond what a regular academic journal can do, and to make them more widely, globally, and swiftly available. _________________________________________________________________________ TABLE OF CONTENTS I. Number 69: Mavericks Mavericks: Harvey, Graeber, and the reunification of anarchism and Marxism in world anthropology by Don Kalb II. Number 66: Forging the Urban Commons Transformative cities: A response to Narotzky, Collins, and Bertho by Ida Susser and Stéphane Tonnelat What kind of commons are the urban commons? by Susana Narotzky The urban public sector as commons: Response to Susser and Tonnelat by Jane Collins Urban commons and urban struggles by Alain Bertho Transformative cities: The three urban commons by Ida Susser and Stéphane Tonnelat III. Number 62: What makes our projects anthropological? Civilizational analysis for beginners by Chris Hann IV. Number 61: Wal-Mart, American consumer citizenship, and the 2008 recession Wal-Mart, American consumer citizenship, and the 2008 recession by Jane Collins V. -

Visit of the President to Andhra Pradesh (Rashtrapati Nilayam, Bolarum, Secunderabad & Tirupati) from 26 Dec 2012 to 01 Jan 2013

‘Public’ visit of the President to Andhra Pradesh (Rashtrapati Nilayam, Bolarum, Secunderabad & Tirupati) from 26 Dec 2012 to 01 Jan 2013 COMPOSITION OF DELEGATION (I) President and Family 1. The President 2. The First Lady (II) President’s Secretariat Delegation 1. Lt Gen AK Bakshi, SM, VSM Military Secretary to the President 2. Dr Thomas Mathew Joint Secretary to the President 3. Dr Mohsin Wali Physician to the President 4. Dr NK Kashyap Dy Physician to the President No. of auxiliary staff: 24 (III) Security Staff Total : 07 (IV) Media Delegation - Nil ‘Official’ visit of the President to Tamil Nadu (Chennai) (ex-Hyderabad) on 28 Dec 2012 COMPOSITION OF DELEGATION (I) President and Family 1. The President (II) President’s Secretariat Delegation 1. Lt Gen AK Bakshi, SM, VSM Military Secretary to the President 2. Dr Mohsin Wali Physician to the President No. of auxiliary staff: 15 (III) Security Staff Total : 03 (IV) Media Delegation - Nil ‘Official’ visit of the President to Maharashtra (Solapur, Pandharpur, Pune & Mumbai) (ex-Hyderabad) from 29 to 30 Dec 2012 COMPOSITION OF DELEGATION (I) President and Family 1. The President 2. Son of the President (II) President’s Secretariat Delegation 1. Lt Gen AK Bakshi, SM, VSM Military Secretary to the President 2. Dr Thomas Mathew Joint Secretary to the President 3. Dr Mohsin Wali Physician to the President No. of auxiliary staff: 16 (III) Security Staff Total : 06 (IV) Media Delegation - Nil ‘Official’ visit of the President to West Bengal (Kolkata) from 02 to 03 Jan 2013 COMPOSITION OF DELEGATION (I) President and Family 1. -

Electoral Roll

ELECTORAL ROLL - 2017 STATE - (S28) UTTARAKHAND No., Name and Reservation Status of Assembly Constituency: 53-Jageshwar(GEN) Last Part No., Name and Reservation Status of Parliamentary Service Constituency in which the Assembly Constituency is located: 3-Almora(SC) Electors 1. DETAILS OF REVISION Year of Revision : 2017 Type of Revision : De-novo preparation Qualifying Date : 01.01.2017 Date of Draft Publication: 04.10.2017 2. SUMMARY OF SERVICE ELECTORS A) NUMBER OF ELECTORS 1. Classified by Type of Service Name of Service No. of Electors Members Wives Total A) Defence Services 939 2 941 B) Armed Police Force 0 0 0 C) Foreign Service 0 0 0 Total in Part (A+B+C) 939 2 941 2. Classified by Type of Roll Roll Type Roll Identification No. of Electors Members Wives Total I Original Preliminary Preliminary De-novo 939 2 941 Roll, 2017 preparation of last part of Electoral Roll Net Electors in the Roll 939 2 941 Elector Type: M = Member, W = Wife Page 1 Draft Electoral Roll, 2017 of Assembly Constituency 53-Jageshwar (GEN), (S28)UTTARAKHAND A . Defence Services Sl.No Name of Elector Elector Rank Husband's Regimental Address for House Address Type Sl.No. despatch of Ballot Paper (1) (2) (3) (4) (5) (6) (7) Assam Rifles 1 HARISH RAM M Havildar Headquarters Directorate General BADAYAR (DASHOLA) Assam Rifles, Record Branch, BADAYAR 000000 Laitumkhrah,Shillong-793011 ALMORA 2 KAILASH CHANDRA M Rifleman Headquarters Directorate General NAYA SAMGROLY JOSHI Assam Rifles, Record Branch, JAINTI JAINTI JAINTI Laitumkhrah,Shillong-793011 000000 ALMORA 3 -

1 Revolutionary Pasts

Cambridge University Press 978-1-108-48184-7 — Revolutionary Pasts Ali Raza Excerpt More Information 1 Revolutionary Pasts To articulate what is past does not mean to recognize ‘how it really was’. It means to take control of a memory, as it flashes in a moment of danger.1 Walter Benjamin, On the Concept of History Working on a maize farm deep in the Argentinian heartland in the year 1929, Naina Singh Dhoot was taken aback by an unexpected visit from Rattan Singh, a communist, roving revolutionary, and leader of the Ghadar Party. Prior to his visit, Rattan Singh had already toured Europe, the United States, Canada, and Panama for the party, which had initially been founded by Indian immigrants in North America in 1913 with the single-minded purpose of freeing India from British rule. In the 1920s, the party established links with the Communist International, which enabled it to send its cadres and recruits to Moscow for political and military training. As part of its mission of recruiting new cadres, the party sent its emissaries to Indian diasporas across the world, from North and South America to East Africa and South East Asia. This was how Naina Singh met Rattan Singh, the party’s emissary extraordinaire. Born and raised in the village of Dhoot Kalan, Punjab, Naina Singh had migrated to Singapore in 1927 in search of work. It was in Singapore that he first learnt the poetry of revolution. There, he heard of a collec- tion of poems by Punjabi labourers and farmworkers in North America. The Ghadar di Gunj (Reverberations of Rebellion) lamented the chains of imperialist slavery that bound India and Indians. -

Leqislative Assembly Debates

21st March 1929 THE LEQISLATIVE ASSEMBLY DEBATES (Official Report) Voiuttie III {21st March to 12th April, 1929) FOURTH SESSION OF THE THIRD LEQISLATIVE ASSEMBLY, 1929 DELHI OOVSBNMENT OF INDIA PRESS Legislative Assembly. President: Honoubablb Mb. V. J. P a tk l. Deputy President: Maw lv i Muhammad Yakub, M ,L.A, Panel o f Chairmen: Pandit Madan Mohan Malaviya, M.L.A. Sir Darcv Lindsay, Kt., C.B.E., M.L,A, Sir Pubshotamdas Thakurdas, K t., C,I,E., M .I^ A, Mb. Jamnadas M. Mehta, MJu A, Secretary: Mb, s. C. Gupta, Bab.-at-Law. Assistant o f the Secretary B a i S a h ib D. D u t t . Marshal: C a p t a in S u b a j S in g h B a h a d u b , I .O .M . Committee o Public Petitions: M aulvi Muhammad Yakub, M.L.A., Chairman. Mb. Dwarka Pbasad Misra, M.L.A. Sir Purshotamdas Thakurdas, Kt., CJ.E,, M.B.E.^ M.L.A. Mr. Dhibendra Kanta Lahiri Chaudhury, M.L.A. Kawab Sib Sahibzada A bdul Qajyum, K.C.I.E., M.L.A. COHTENTS. Volum e 111 March to lith April, 1929. PaobS. Thursday^ 21st March, 1921H- Member Sworn 2265 Short >Totice Question and Answer 2265-71 Motion for Adjournment—Raids and Arrests in Several Parts of India—l^ave granted by the Honourable the President but disallowed by H. E. the Viceroy and Governor General. 2271-77, The Indian Finance Bill—Motion to consider adopted and dis cussion on the consideration of clauses adjourned 2277-2322 Friday, 22nd M ardi, 1029— Questions and Answers .. -

Date of Birth Rollno Relax Ground Category Division Degree Age Pref

Name Date of Birth Degree Category RollNo Ref No Address Pref.City Age Father's Name Division Relax Ground Stream 1 SUDHANSHU MIG 14 HOUSING BOARD DELHI 01/03/1978 OTG 2,006 COLONY BARARI, BHAGALPUR, BIHAR 812003 ENGLISH 38Y 10M 26D KUMAR SHIV SHANKAR SINGH 2 AMOL SHREE VIHAR, SECT. NO. B, DELHI 04/11/1985 SC 826 BUILDING NO. G, FLAT NO. 5, NEAR APPU GHAR, NIGDI, PUNE HARISHCHANDRA 411044 ENGLISH 31Y 2M 23D DHAMDHERE HARISHCHANDRA G DHAMDHERE 3 RAHUL DHAMMADEED NAGAR, BINKI DELHI 26/08/1987 SC 1,125 MANGALWARI LAY OUT, NAGPUR SHANKAR 440017 ENGLISH 29Y 5M 1D MATE SHANKAR GOPALA MATE 4 GUNJAN H.NO. 919/27, GANDHI DELHI 15/06/1993 GEN 2,531 NAGAR, ROHTAK HARYANA 124001 ENGLISH 23Y 7M 12D GULSHAN KUMAR 5 SUNEEL VIJAY PURAM COLONY, DELHI 12/02/1995 GEN 1,975 BEHIND MEHAL, SHIVPURI, DISTRICT SHIVPURI, M.P. 1 Name Date of Birth Degree Category RollNo Ref No Address Pref.City Age Father's Name Division Relax Ground Stream 473551 ENGLISH 22Y 0M 15D DUBEY LAXMAN PRASAD DUBEY 6 VIPUL 25-B, JANYUG APARTMENTS, DELHI 24/01/1989 SC 1,058 BEHIND ROHINI COURTS, SECTOR-14, ROHINI, DELHI 110085 ENGLISH 28Y 1M 3D SAROHA HARI KISHAN SAROHA 7 ASHOK 62/7, ASHOK NAGAR, POST DELHI 07/08/1976 GEN 1,356 OFFICE TILAK NAGAR, NEW DELHI KUMAR 110018 ENGLISH GOVT.SERVICE 40Y 5M 20D SALUJA S.P. SALUJA 8 aa 2,923 26Y 4M 16D aa aa 9 a 1,312 29Y 6M 25D 2 Name Date of Birth Degree Category RollNo Ref No Address Pref.City Age Father's Name Division Relax Ground Stream 10 a 300 22Y 10M 25D 11 SUDHIR 6-A, MC COLONY, NEAR DELHI 01/04/1990 GEN 778 BHARAT MATA MANDIR, HISAR 125001 ENGLISH 26Y 9M 26D VIRENDER SINGH 12 RIZWAN F1/15 JOGA BAI EXTN. -

4. Leftist Politics in British India, Himayatullah

Leftist Politics in British India: A Case Study of the Muslim Majority Provinces Himayatullah Yaqubi ∗ Abstract The paper is related with the history and political developments of the various organizations and movements that espoused a Marxist, leftist and socialist approach in their policy formulation. The approach is to study the left’s political landscape within the framework of the Muslim majority provinces which comprised Pakistan after 1947. The paper would deal those political groups, parties, organizations and personalities that played significant role in the development of progressive, socialist and non-communal politics during the British rule. Majority of these parties and groups merged together in the post-1947 period to form the National Awami Party (NAP) in July 1957. It is essentially an endeavour to understand the direction of their political orientation in the pre-partition period to better comprehend their position in the post-partition Pakistan. The ranges of the study are much wide in the sense that it covers all the provinces of the present day Pakistan, including former East Pakistan. It would also take up those political figures that were influenced by socialist ideas but, at the same time, worked for the Muslim League to broaden its mass organization. In a nutshell the purpose of the article is to ∗ Research Fellow, National Institute of Historical and Cultural Research, Centre of Excellence, Quaid-i-Azam University, Islamabad 64 Pakistan Journal of History and Culture, Vol.XXXIV, No.I, 2013 study the pre-partition political strategies, line of thinking and ideological orientation of the components which in the post- partition period merged into the NAP in 1957. -

Salt Satyagraha the Watershed

I VOLUME VI Salt Satyagraha The Watershed SUSHILA NAYAR NAVAJIVAN PUBLISHING HOUSE AHMEDABAD-380014 MAHATMA GANDHI Volume VI SALT SATYAGRAHA THE WATERSHED By SUSHILA NAYAR First Edition: October 1995 NAVAJIVAN PUBLISHING HOUSE AHMEDABAD 380014 MAHATMA GANDHI– Vol. VI | www.mkgandhi.org The Salt Satyagraha in the north and the south, in the east and the west of India was truly a watershed of India's history. The British rulers scoffed at the very idea of the Salt March. A favourite saying in the barracks was: "Let them make all the salt they want and eat it too. The Empire will not move an inch." But as the Salt Satyagraha movement reached every town and village and millions of people rose in open rebellion, the Empire began to shake. Gandhi stood like a giant in command of the political storm. It was not however only a political storm. It was a moral and cultural storm that rose from the inmost depths of the soul of India. The power of non-violence came like a great sunrise of history. ... It was clear as crystal that British rule must give way before the rising tide of the will of the people. For me and perhaps for innumerable others also this was at the same time the discovery of Gandhi and our determination to follow him whatever the cost. (Continued on back flap) MAHATMA GANDHI– Vol. VI | www.mkgandhi.org By Pyarelal The Epic Fast Status of Indian Princes A Pilgrimage for Peace A Nation-Builder at Work Gandhian Techniques in the Modern World Mahatma Gandhi -The Last Phase (Vol. -

Notice for Writtten EXAM (List of Provisonlly Eligible Candidates)

Notice of Written Examination The Written Exam for the following Posts will be conducted on 02.11.2008 (Sunday) in two shifts. The details are as under:- S.No. Name of the Post Shift Timings 1 Manager (Electrical /Cargo/ Commercial Morning Shift 10.00 AM Jr.Executive (P&A/ Arch.) 2 Manager (Airport Operation/Fire Service) Evening Shift 02.30 PM Jr.Executive (IT/Eqpt.) Admit cards have been dispatched to the provisionally eligible candidates individually. In case of non-receipt of Admit Card, duplicate Admit Card can be had in person from this office from 22nd October,08 except Saturday/Sunday and Gagetted holiday. Candidates who did not come here in person are advised to go directly to the examination centre (As per Centre for written exam adopted in the application form) and request to Nodal Officer, AAI at the Venue on the Schedule date of exam. It may be noted that duplicate Admit Card will be issued only those candidates whose name are exist in our master list of provisionally eligible candidates. Candidates are also advised to bring one passport size photo, identical to the photo pasted on their application forms for further enquires, candidates can contact over telephone No. 011-24632950 Extn.2431/2449/2467 from 9.30 AM to 5.30PM.on all working days. The names of the examination centre are as under:- S.No. Centre Venue for Morning Shift- Venue for Evening Shift- For Manager (Electrical For Manager (Airport /Cargo /Commercial) and Operation/Fire Service) JE (P&A/Arch) and JE (IT/Equpt) Kendriya Vidalaya No.1, 1. -

Visit of the Presiden

‘Official’ visit of the President to West Bengal (Kolkata, Chanchal, Malda District) & ‘Public’visit of the President to Andaman & Nicobar Island (Port Blair, Havelock Island & Car Nicobar) from 09-13 Jan 2014 COMPOSITION OF DELEGATION (I) President and Family 1. The President (II) President’s Secretariat Delegation 1. Shri Venu Rajamony Press Secretary to the President 2. Maj Gen Anil Khosla, SM, VSM Military Secretary to the President 3. Dr Mohsin Wali Physician to the President No. of auxiliary staff : 19 (III) Security Staff Total : 08 (iv) Media Delegation 1. Shri Gautam Lahiri Chief of Bureau, Sangbad Pratideen 2. Shri Arunagshu Chakravarty Editor, Andaman Observer 3. Shri Shankhadip Das Special Correspondent, Ananda Bazar Patrika 4. Shri Amandeep Shukla Principal Correspondent, PTI 5. Shri Manjit Thakur Correspondent, Doordarshan 6. Shri Jagpal Singh Cameraman, Doordarshan 7. Shri Yogesh Goel Cameraperson, ANI ‘Official’ visit of the President to Maharashtra (Baramati, Distt Pune) on 19 Jan 2014 COMPOSITION OF DELEGATION (I) President and Family 1. The President (II) President’s Secretariat Delegation 1. Maj Gen Anil Khosla, SM, VSM Military Secretary to the President 2. Dr NK Kashyap Dy Physician to the President 3. Smt Shamima Siddiqui Dy Press Secretary to the President No. of auxiliary staff : 12 (III) Security Staff Total : 03 (iv) Media Delegation 1. Shri Anil Padmanabhan Dy Managing Editor, Mint 2. Ms Mamuni Das Senior Assistant Editor, Hindu Business Line 3. Shri Samiran Sarangi Principal Correspondent, PTI 4. Shri Sudhir Kumar Yadav Corresondent, Doordarshan 5. Shri AMG Surender Cameraperson, Doordarshan 6. Shri Shiv Shankar Cameraman, ANI ‘Official’ visit of the President to Maharashtra (Mumbai, Nagpur & Gondia) From 08-09 Feb 2014 COMPOSITION OF DELEGATION (I) President and Family 1. -

Decolonizing Anarchism

Praise for Dec%nilingAnarchism Maia Ramnath offers a refreshingly different perspec tive on anticolonial movements in India, not only by fo cusing on little-remembered anarchist exiles such as Har Dayal, Mukerji and Acharya but more important, high lighting the persistent trend that sought to strengthen au tonomous local communities against the modern nation state. While Gandhi, the self-proclaimed philosophical anarchist, becomes a key figure in this antiauthoritarian history, there are other more surprising cases that Ramnath brings to light. A superbly original book. -Partha Chatterj ee, author ofLin ellgesPolitical of Society: Studiesin Postcolonial Democracy "This is a stunningly impactful and densely researched book. Maia Ramnath has offereda vital contribution to our understanding of the long historical entanglement between liberation struggles, anticolonialism, and the radical move ment of oppressed peoples against the modern nation-state. She audaciously reframes the dominant narrative ofIndian radicalism by detailing its explosive and ongoing symbiosis with decolonial anarchism." -Dylan Rodriguez, author of SuspendedApocalypse: WhiteSupremacy, Genocide, and the Filipino Condition Anarchist Interventions: An I AS/ AK Press Book Series Radical ideas can open up spaces fo r radical actions, by illuminating hierarchical power relations and drawing out possibilities fo r liberatory social transformations. The Anarchist Intervention series-a collaborative project between the Institute fo r Anarchist Studies (lAS) and AK Press-strives to contribute to the development of relevant, vital anarchist theory and analysis by intervening in contemporary discussions. Wo rks in this series will look at twenty-first-century social conditions-including social structures and oppression, their historical trajectories, and new forms of domination, to name a fe w-as well as reveal opportunities fo r different tomorrows premised on hori zontal, egalitarian fo rms of self-organization. -

RSETI Directory

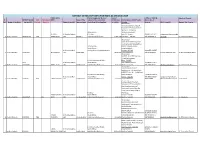

CONTACT DETAILS OF RSETIs PAN INDIA AS ON 30.06.2019 NAME of the Name, Designation & email Date of Tel/Fax of RSETI & Details of Director Sl. DISTRICT NAME LWE Aspirational RSETI Name of the address of the immediate Establishme Postal Address of RSETI with Mobile No. of No. Name of the State (as per MIS) Districts Districts Name of the SDR Sponsor Bank Controlling Office Head(e.g. nt of RSETI Pincode Director RSETI E-mail ID Name of the Director The Director Rural Development and Self Employment Training Institute Beside S.K. University M.Janardhan Stadium Itukulapalli, RUDSETI- B Chandra Sekhar - ED, Ujire Post: S.V. Puram, (O) 08554-255925 rudsetiananthapuramu@g 1 Andhra Pradesh ANANTAPUR YES ANANTAPUR 166 RUDSETI [email protected] 8-Mar-98 Anantapur – 515 003 (M) 9440905479 mail.com Sri P Venkataramana The Director Indian Bank Self Employment Training Institute 2-1264/6,1st S Dushyantan Floor, B.V.Reddy Colony, Nodal Officer kongareddypalli, B Chandra Sekhar - [email protected] Chittoor- 517 001 (O) 08572-232757 2 Andhra Pradesh CHITTOOR IB-CHITTOOR 166 Indian Bank 19-Sep-09 (Andhra Pradesh) (M) 9440758676 [email protected] Sri M.R.Janardhana Naidu The Director AB RSETI, Near TTDC (Velugu Office), Satrampadu R. Vishnu Vardhan Reddy Eluru - 534 007 WEST B Chandra Sekhar - Nodal Officer West Godavari District (O) 08812-253975 3 Andhra Pradesh GODAVARI ABIRD- ELUR 166 Andhra Bank [email protected] 8-Oct-05 (Andhra Pradesh) (M) 9866094383 [email protected] Sri J Shanmukha Rao The Director Andhra Bank Rural Self Employment Training Institute (ABRDT),D.No.