The Origin of Plastids By: Cheong Xin Chan, Ph.D

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pinpointing the Origin of Mitochondria Zhang Wang Hanchuan, Hubei

Pinpointing the origin of mitochondria Zhang Wang Hanchuan, Hubei, China B.S., Wuhan University, 2009 A Dissertation presented to the Graduate Faculty of the University of Virginia in Candidacy for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Biology University of Virginia August, 2014 ii Abstract The explosive growth of genomic data presents both opportunities and challenges for the study of evolutionary biology, ecology and diversity. Genome-scale phylogenetic analysis (known as phylogenomics) has demonstrated its power in resolving the evolutionary tree of life and deciphering various fascinating questions regarding the origin and evolution of earth’s contemporary organisms. One of the most fundamental events in the earth’s history of life regards the origin of mitochondria. Overwhelming evidence supports the endosymbiotic theory that mitochondria originated once from a free-living α-proteobacterium that was engulfed by its host probably 2 billion years ago. However, its exact position in the tree of life remains highly debated. In particular, systematic errors including sparse taxonomic sampling, high evolutionary rate and sequence composition bias have long plagued the mitochondrial phylogenetics. This dissertation employs an integrated phylogenomic approach toward pinpointing the origin of mitochondria. By strategically sequencing 18 phylogenetically novel α-proteobacterial genomes, using a set of “well-behaved” phylogenetic markers with lower evolutionary rates and less composition bias, and applying more realistic phylogenetic models that better account for the systematic errors, the presented phylogenomic study for the first time placed the mitochondria unequivocally within the Rickettsiales order of α- proteobacteria, as a sister clade to the Rickettsiaceae and Anaplasmataceae families, all subtended by the Holosporaceae family. -

Plastid Variegation and Concurrent Anthocyanin Variegation in Salpiglossis1

PLASTID VARIEGATION AND CONCURRENT ANTHOCYANIN VARIEGATION IN SALPIGLOSSIS1 E. E. DALE AND OLIVE L. REES-LEONARD Union College, Schmectady, N. Y. Received December 30, 1938 VARIEGATED strain of Salpiglossis has now been carried in the A senior author's cultures for eight years. This strain is unique in that the variegation affects both the leaves and the flowers as reported in a preliminary note (DALEand REES-LEONARD1935). The variegation pat- tern, typical of many chlorophyll variegations, is shown in the leaves of an adult plant (figure I). The leaves are marked by sharply defined spots of diverse sizes and shapes which vary in color from light green to white. It should be noted that white branches have not been found on the varie- gated plants. In seedlings (figure 2), the variegation shows some rather striking differences from the adult type. The pattern is coarser with rela- tively greater amounts of white or pale tissue. This increase in chlorophyll deficient tissue often results in crumpling or asymmetry of the leaves. In variegated seedlings, also, the bases of the leaf blades frequently exhibit white or pale borders. For the sake of comparison, a normal seedling (figure 4) is illustrated. The seedlings were of the same age, growth being retarded in variegated plants. The flower color in anthocyanin types of Salpiglossis is due to a combina- tion of anthocyanin with yellow plastids, Absence of anthocyanin gives yellow flowers. Both the yellow and anthocyanin colors show variegation. Naturally, the color of the pale areas in variegated flowers depends upon the ground color of the flower, yellow flowers having very light yellow spots and anthocyanin colors showing an apparent modification of the anthocyanin, the nature of which is discussed later. -

Origin and Evolution of Plastids and Mitochondria : the Phylogenetic Diversity of Algae

Cah. Biol. Mar. (2001) 42 : 11-24 Origin and evolution of plastids and mitochondria : the phylogenetic diversity of algae Catherine BOYEN*, Marie-Pierre OUDOT and Susan LOISEAUX-DE GOER UMR 1931 CNRS-Goëmar, Station Biologique CNRS-INSU-Université Paris 6, Place Georges-Teissier, BP 74, F29682 Roscoff Cedex, France. *corresponding author Fax: 33 2 98 29 23 24 ; E-mail: [email protected] Abstract: This review presents an account of the current knowledge concerning the endosymbiotic origin of plastids and mitochondria. The importance of algae as providing a large reservoir of diversified evolutionary models is emphasized. Several reviews describing the plastidial and mitochondrial genome organization and gene content have been published recently. Therefore we provide a survey of the different approaches that are used to investigate the evolution of organellar genomes since the endosymbiotic events. The importance of integrating population genetics concepts to understand better the global evolution of the cytoplasmically inherited organelles is especially emphasized. Résumé : Cette revue fait le point des connaissances actuelles concernant l’origine endosymbiotique des plastes et des mito- chondries en insistant plus particulièrement sur les données portant sur les algues. Ces organismes représentent en effet des lignées eucaryotiques indépendantes très diverses, et constituent ainsi un abondant réservoir de modèles évolutifs. L’organisation et le contenu en gènes des génomes plastidiaux et mitochondriaux chez les eucaryotes ont été détaillés exhaustivement dans plusieurs revues récentes. Nous présentons donc une synthèse des différentes approches utilisées pour comprendre l’évolution de ces génomes organitiques depuis l’événement endosymbiotique. En particulier nous soulignons l’importance des concepts de la génétique des populations pour mieux comprendre l’évolution des génomes à transmission cytoplasmique dans la cellule eucaryote. -

Origin and Evolution of Eukaryotic Compartmentalization

TESI DOCTORAL UPF 2016 Origin and evolution of eukaryotic compartmentalization Alexandros Pittis Director Dr. Toni Gabaldon´ Comparative Genomics Group Bioinformatics and Genomics Department Centre for Genomic Regulation (CRG) To my father Stavros for the PhD he never did Acknowledgments Looking back at the years of my PhD in the Comparative Genomics group at CRG, I feel it was equally a process of scientific, as well as personal development. All this time I was very privileged to be surrounded by people that offered me their generous support in both fronts. And they were available in the very moments that I was fighting more myself than the unsolvable (anyway) comparative genomics puzzles. I hope that in the future I will have many times the chance to express them my appreciation, way beyond these few words. First, to Toni, my supervisor, for all his support, and patience, and confidence, and respect, especially at the moments that things did not seem that promising. He offered me freedom, to try, to think, to fail, to learn, to achieve that few enjoy during their PhD, and I am very thankful to him. Then, to my good friends and colleagues, those that I found in the group already, and others that joined after me. A very special thanks to Marinita and Jaime, for all their valuable time, and guidance and paradigm, which nevertheless I never managed to follow. They have both marked my phylogenomics path so far and I cannot escape. To Les and Salvi, my fellow students and pals at the time for all that we shared; to Gab and Fran and Dam, for -

Virus World As an Evolutionary Network of Viruses and Capsidless Selfish Elements

Virus World as an Evolutionary Network of Viruses and Capsidless Selfish Elements Koonin, E. V., & Dolja, V. V. (2014). Virus World as an Evolutionary Network of Viruses and Capsidless Selfish Elements. Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews, 78(2), 278-303. doi:10.1128/MMBR.00049-13 10.1128/MMBR.00049-13 American Society for Microbiology Version of Record http://cdss.library.oregonstate.edu/sa-termsofuse Virus World as an Evolutionary Network of Viruses and Capsidless Selfish Elements Eugene V. Koonin,a Valerian V. Doljab National Center for Biotechnology Information, National Library of Medicine, Bethesda, Maryland, USAa; Department of Botany and Plant Pathology and Center for Genome Research and Biocomputing, Oregon State University, Corvallis, Oregon, USAb Downloaded from SUMMARY ..................................................................................................................................................278 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................................278 PREVALENCE OF REPLICATION SYSTEM COMPONENTS COMPARED TO CAPSID PROTEINS AMONG VIRUS HALLMARK GENES.......................279 CLASSIFICATION OF VIRUSES BY REPLICATION-EXPRESSION STRATEGY: TYPICAL VIRUSES AND CAPSIDLESS FORMS ................................279 EVOLUTIONARY RELATIONSHIPS BETWEEN VIRUSES AND CAPSIDLESS VIRUS-LIKE GENETIC ELEMENTS ..............................................280 Capsidless Derivatives of Positive-Strand RNA Viruses....................................................................................................280 -

Evidence Supporting an Antimicrobial Origin of Targeting Peptides to Endosymbiotic Organelles

cells Article Evidence Supporting an Antimicrobial Origin of Targeting Peptides to Endosymbiotic Organelles Clotilde Garrido y, Oliver D. Caspari y , Yves Choquet , Francis-André Wollman and Ingrid Lafontaine * UMR7141, Institut de Biologie Physico-Chimique (CNRS/Sorbonne Université), 13 Rue Pierre et Marie Curie, 75005 Paris, France; [email protected] (C.G.); [email protected] (O.D.C.); [email protected] (Y.C.); [email protected] (F.-A.W.) * Correspondence: [email protected] These authors contributed equally to this work. y Received: 19 June 2020; Accepted: 24 July 2020; Published: 28 July 2020 Abstract: Mitochondria and chloroplasts emerged from primary endosymbiosis. Most proteins of the endosymbiont were subsequently expressed in the nucleo-cytosol of the host and organelle-targeted via the acquisition of N-terminal presequences, whose evolutionary origin remains enigmatic. Using a quantitative assessment of their physico-chemical properties, we show that organelle targeting peptides, which are distinct from signal peptides targeting other subcellular compartments, group with a subset of antimicrobial peptides. We demonstrate that extant antimicrobial peptides target a fluorescent reporter to either the mitochondria or the chloroplast in the green alga Chlamydomonas reinhardtii and, conversely, that extant targeting peptides still display antimicrobial activity. Thus, we provide strong computational and functional evidence for an evolutionary link between organelle-targeting and antimicrobial peptides. Our results support the view that resistance of bacterial progenitors of organelles to the attack of host antimicrobial peptides has been instrumental in eukaryogenesis and in the emergence of photosynthetic eukaryotes. Keywords: Chlamydomonas; targeting peptides; antimicrobial peptides; primary endosymbiosis; import into organelles; chloroplast; mitochondrion 1. -

The Photosynthetic Endosymbiont in Cryptomonad Cells Produces Both Chloroplast and Cytoplasmic-Type Ribosomes

Journal of Cell Science 107, 649-657 (1994) 649 Printed in Great Britain © The Company of Biologists Limited 1994 JCS6601 The photosynthetic endosymbiont in cryptomonad cells produces both chloroplast and cytoplasmic-type ribosomes Geoffrey I. McFadden1,*, Paul R. Gilson1 and Susan E. Douglas2 1Plant Cell Biology Research Centre, School of Botany, University of Melbourne, Parkville, Victoria, 3052, Australia 2Institute of Marine Biosciences, National Research Council of Canada, 1411 Oxford St, Halifax, Nova Scotia B3H 3Z1, Canada *Author for correspondence SUMMARY Cryptomonad algae contain a photosynthetic, eukaryotic tion machinery. We also localized transcripts of the host endosymbiont. The endosymbiont is much reduced but nucleus rRNA gene. These transcripts were found in the retains a small nucleus. DNA from this endosymbiont nucleolus of the host nucleus, and throughout the host nucleus encodes rRNAs, and it is presumed that these cytoplasm, but never in the endosymbiont compartment. rRNAs are incorporated into ribosomes. Surrounding the Our rRNA localizations indicate that the cryptomonad cell endosymbiont nucleus is a small volume of cytoplasm produces two different of sets of cytoplasmic-type proposed to be the vestigial cytoplasm of the endosymbiont. ribosomes in two separate subcellular compartments. The If this compartment is indeed the endosymbiont’s results suggest that there is no exchange of rRNAs between cytoplasm, it would be expected to contain ribosomes with these compartments. We also used the probe specific for the components encoded by the endosymbiont nucleus. In this endosymbiont rRNA gene to identify chromosomes from paper, we used in situ hybridization to localize rRNAs the endosymbiont nucleus in pulsed field gel electrophore- encoded by the endosymbiont nucleus of the cryptomonad sis. -

GUN1 and Plastid RNA Metabolism: Learning from Genetics

cells Opinion GUN1 and Plastid RNA Metabolism: Learning from Genetics Luca Tadini y , Nicolaj Jeran y and Paolo Pesaresi * Department of Biosciences, University of Milan, 20133 Milan, Italy; [email protected] (L.T.); [email protected] (N.J.) * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +39-02503-15057 These authors contributed equally to the manuscript. y Received: 29 September 2020; Accepted: 14 October 2020; Published: 16 October 2020 Abstract: GUN1 (genomes uncoupled 1), a chloroplast-localized pentatricopeptide repeat (PPR) protein with a C-terminal small mutS-related (SMR) domain, plays a central role in the retrograde communication of chloroplasts with the nucleus. This flow of information is required for the coordinated expression of plastid and nuclear genes, and it is essential for the correct development and functioning of chloroplasts. Multiple genetic and biochemical findings indicate that GUN1 is important for protein homeostasis in the chloroplast; however, a clear and unified view of GUN10s role in the chloroplast is still missing. Recently, GUN1 has been reported to modulate the activity of the nucleus-encoded plastid RNA polymerase (NEP) and modulate editing of plastid RNAs upon activation of retrograde communication, revealing a major role of GUN1 in plastid RNA metabolism. In this opinion article, we discuss the recently identified links between plastid RNA metabolism and retrograde signaling by providing a new and extended concept of GUN1 activity, which integrates the multitude of functional genetic interactions reported over the last decade with its primary role in plastid transcription and transcript editing. Keywords: GUN1; RNA polymerase; transcript accumulation; transcript editing; retrograde signaling 1. -

Plastid in Human Parasites

SCIENTIFIC CORRESPONDENCE being otherwise homo Plastid in human geneous. The 35-kb genome-containing organ parasites elle identified here did not escape the attention of early Sm - The discovery in malarial and toxo electron microscopists who plasmodial parasites of genes normally - not expecting the pres occurring in the photosynthetic organelle ence of a plastid in a proto of plants and algae has prompted specula zoan parasite like tion that these protozoans might harbour Toxoplasma - ascribed to it a vestigial plastid1• The plastid-like para various names, including site genes occur on an extrachromosomal, 'Hohlzylinder' (hollow cylin maternally inherited2, 35-kilobase DNA der), 'Golgi adjunct' and circle with an architecture reminiscent of 'grof3e Tilkuole mit kriiftiger that of plastid genomes3•4• Although the Wandung' (large vacuole 35-kb genome is distinct from the 6-7-kb with stout surrounds) ( see linear mitochondrial genome3-6, it is not refs cited in ref. 9). Our pre known where in the parasite cells the plas liminary experiments with tid-like genome resides. Plasmodium falciparum, the To determine whether a plastid is pre causative agent of the most sent, we used high-resolution in situ lethal form of malaria, hybridization7 to localize transcripts of a identify an organelle (not plastid-like 16S ribosomal RNA gene shown) which appears sim from Toxoplasma gondii8, the causative ilar to the T. gondii plastid. agent of toxoplasmosis. Transcripts accu The number of surrounding mulate in a small, ovoid organelle located membranes in the P. anterior to the nucleus in the mid-region falciparum plastid, and its of the cell (a, b in the figure). -

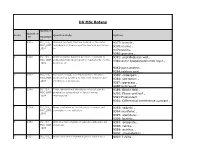

DU Msc Botany

DU MSc Botany Question Question Sr.No Question Body Options Id Descripti on 1 2345 DU_J19_ Channel proteins that are located in the outer 9377: barrels , MSC_BOT membrane of Gram-negative bacteria are known 9378:murins , _Q01 as 9379:porins, 9380:granules , 2 2346 DU_J19_ Gram-negative bacteria are more resistant to 9381: peptidoglycan wall., MSC_BOT antibiotics than Gram-positive bacteria due to the 9382:outer lipopolysaccharide layer., _Q02 presence of 9383:porin protein., 9384:teichoic acid. , 3 2347 DU_J19_ Dormant, tough, non-reproductive structure, 9385: endospore , MSC_BOT produced by bacteria to tide over unfavourable 9386: sclerotium , _Q03 conditions is known as: 9387:sporocarp , 9388:heterocyst , 4 2348 DU_J19_ Three-dimensional structures of a cell can be 9389: Bright field , MSC_BOT studied by using which of the following 9390: Phase contrast , _Q04 microscopes? 9391:Fluorescent , 9392: Differential interference contrast , 5 2349 DU_J19_ Algae that grow at the interface of water and 9393: epipelic , MSC_BOT atmosphere are called as 9394:neustonic , _Q05 9395: planktonic , 9396: benthic, 6 2350 DU_J19_ Orthorhombic crystals of calcium carbonate are 9397: aragonite., MSC_BOT known as 9398: calcite. , _Q06 9399: detritus. , 9400: stromatolites. , 7 2351 DU_J19_ Which one of the following amino acids has a 9401: Lysine , MSC_BOT nonpolar, aliphatic R group? _Q07 7 2351 DU_J19_ Which one of the following amino acids has a MSC_BOT nonpolar, aliphatic R group? 9402: Histidine , _Q07 9403: Arginine , 9404: Glycine, 8 2352 DU_J19_ -

Identification and Characterisation of Endogenous Avian Leukosis Virus Subgroup E (ALVE) Insertions in Chicken Whole Genome Sequencing Data Andrew S

Mason et al. Mobile DNA (2020) 11:22 https://doi.org/10.1186/s13100-020-00216-w RESEARCH Open Access Identification and characterisation of endogenous Avian Leukosis Virus subgroup E (ALVE) insertions in chicken whole genome sequencing data Andrew S. Mason1,2* , Ashlee R. Lund3, Paul M. Hocking1ˆ, Janet E. Fulton3† and David W. Burt1,4† Abstract Background: Endogenous retroviruses (ERVs) are the remnants of retroviral infections which can elicit prolonged genomic and immunological stress on their host organism. In chickens, endogenous Avian Leukosis Virus subgroup E (ALVE) expression has been associated with reductions in muscle growth rate and egg production, as well as providing the potential for novel recombinant viruses. However, ALVEs can remain in commercial stock due to their incomplete identification and association with desirable traits, such as ALVE21 and slow feathering. The availability of whole genome sequencing (WGS) data facilitates high-throughput identification and characterisation of these retroviral remnants. Results: We have developed obsERVer, a new bioinformatic ERV identification pipeline which can identify ALVEs in WGS data without further sequencing. With this pipeline, 20 ALVEs were identified across eight elite layer lines from Hy-Line International, including four novel integrations and characterisation of a fast feathered phenotypic revertant that still contained ALVE21. These bioinformatically detected sites were subsequently validated using new high- throughput KASP assays, which showed that obsERVer was highly precise and exhibited a 0% false discovery rate. A further fifty-seven diverse chicken WGS datasets were analysed for their ALVE content, identifying a total of 322 integration sites, over 80% of which were novel. Like exogenous ALV, ALVEs show site preference for proximity to protein-coding genes, but also exhibit signs of selection against deleterious integrations within genes. -

Can We Understand Evolution Without Symbiogenesis?

Can We Understand Evolution Without Symbiogenesis? Francisco Carrapiço …symbiosis is more than a mere casual and isolated biological phenomenon: it is in reality the most fundamental and universal order or law of life. Hermann Reinheimer (1915) Abstract This work is a contribution to the literature and knowledge on evolu- tion that takes into account the biological data obtained on symbiosis and sym- biogenesis. Evolution is traditionally considered a gradual process essentially consisting of natural selection, conducted on minimal phenotypical variations that are the result of mutations and genetic recombinations to form new spe- cies. However, the biological world presents and involves symbiotic associations between different organisms to form consortia, a new structural life dimension and a symbiont-induced speciation. The acknowledgment of this reality implies a new understanding of the natural world, in which symbiogenesis plays an important role as an evolutive mechanism. Within this understanding, symbiosis is the key to the acquisition of new genomes and new metabolic capacities, driving living forms’ evolution and the establishment of biodiversity and complexity on Earth. This chapter provides information on some of the key figures and their major works on symbiosis and symbiogenesis and reinforces the importance of these concepts in our understanding of the natural world and the role they play in the establishing of the evolutionary complexity of living systems. In this context, the concept of the symbiogenic superorganism is also discussed. Keywords Evolution · Symbiogenesis · Symbiosis · Symbiogenic superorgan- ism · New paradigm F. Carrapiço (*) Centre for Ecology Evolution and Environmental Change (CE3C); Centre for Philosophy of Science, Department of Plant Biology, Faculty of science, University of Lisbon, Lisbon, Portugal e-mail: [email protected] © Springer International Publishing Switzerland 2015 81 N.