In the Social Studies Are Also Included. Appendixes Present a List

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 2001-2003 CATALOG UPDATE Changes Effective 2002-2003

2001-2003 CATALOG UPDATE Changes effective 2002-2003 ASIAN STUDIES MINOR Students choosing this interdisciplinary minor have three options. Those whose primary interest is in East Asia must satisfy Option I. Those interested primarily in south or Pan-Asian topics must choose Option II. Those interested mainly in Asian American issues will choose Option III. Students may double-count two courses toward their major or toward a second minor. With the approval of the committee, courses taken in International Studies Exchange or Study Abroad Programs in Asian regions can be substituted for courses below. OPTION I East Asian Worksheet The East Asian Option requires successful completion of 18 hours of courses listed below: Intermediate proficiency in either Chinese or Japanese is mandatory. CHIN 212 Intermediate Chinese I CHIN 213 Intermediate Chinese II JAPN 201 Intermediate Japanese I JAPN 202 Intermediate Japanese II (total of 6 hours) Select the remaining 12 hours from the three areas listed below. Students must have at least one course from each of the three areas listed below. At least two courses should be at or above the 300-level. Area I LLFL 429 Studies in Chinese: 3rd Year I LLFL 429 Studies in Chinese: 3rd Year II JAPN 301 Advanced Japanese I JAPN 302 Advanced Japanese II ENG 225 World Literatures: Chronology—Anytime, Asia ENG 307 Twentieth Century World Literature—Asia ENG 320 Asian Literature ENG 322 Studies in World Cinema—Asia FREN 401 Francophone Indochinese Literature Area II HIST 141 East Asian Civilization I HIST 142 East Asian Civilization II HIST 434 History of Japan I HIST 435 History of Japan II HIST 448 History of China I HIST 449 History of China II GEOG 322 Geography of Asia Area III PHRE 347 Studies in Religion II—the Hindu, Buddhist, Japanese, Taoist, Yoga, or Chinese Traditions PHRE 362 Women in Buddhism PHRE 363 Women in Chinese Religion CHIN 311 Chinese Culture 1 OPTION II South or Pan-Asian Worksheet The South or Pan-Asian Option requires successful completion of at least 15 hours taken from the courses listed below. -

2005 CALIFORNIA MEN's WATER POLO FACTS and FIGURES TABLE of CONTENTS Location: Berkeley, CA Facts and Figures, Schedule

2005 CALIFORNIA MEN'S WATER POLO FACTS AND FIGURES TABLE OF CONTENTS Location: Berkeley, CA Facts and Figures, Schedule ................................................................... 1 Enrollment: 32,000 2005 Season Outlook .......................................................................... 2-3 Founded: 1868 2005 Roster ............................................................................................ 3 Nickname: Golden Bears The Coaching Staff ................................................................................. 4 Colors: Blue and Gold Golden Bear Profiles ......................................................................... 5-11 Conference: Mountain Pacific Sports Federation 2004 Season In Review ........................................................................ 12 Pool: Spieker Aquatics Complex (2,000) 2004 Final Stats, Results ..................................................................... 13 Pool Dimensions: 50-meters by 25 yards 2004 Final MPSF Results & Honors .................................................. 14 Chancellor: Robert J. Birgeneau Year-by-Year Results ........................................................................... 15 Athletic Director: Sandy Barbour California All-Americans/Team Awards ............................................. 16 Head Coach: Kirk Everist Cal Water Polo History ....................................................................... 17 Years at Cal: Fourth season NCAA History ................................................................................... -

Working Paper Series

東南亞研究中心 Southeast Asia Research Centre Frances Antoinette CRUZ Assistant Professor of German Department of European Languages University of the Philippines, Diliman Halfway between Emporia and Westphalia: Exploring Networks and Middle Powers in Asia Working Paper Series No. 179 July 2016 Halfway between Emporia and Westphalia: Exploring Networks and Middle Powers in Asia Abstract The significance of middle powers has been theorized since the Cold War in an effort to ascertain the function of states that did not satisfy the military component of great powers, yet possessed significant economic capability and regional influence to exert power in global affairs. In this essay, the role of middle powers in Asia will be discussed in the context of three concepts in international relations: firstly, the concept of middlepowermanship as seen from a network theory (Latour, 1996; Hafner-Burton, Kahler, & Montgomery, 2009); secondly, in the context of Acharya’s (2014) multiplex in Global IR; which expands the potentials of ‘middlepowermanship’ from a network perspective by incorporating various actants, and thirdly as a conduit for soft power flows, particularly in terms of a socializer (Thies, 2013) or norm diffuser. The second part of the essay will then explore various historical of networks within Asia and to what degree these models ‘fit’ modern interactions between nation states and other actors, and what roles middle powers and middlepowermanship could potentially play in these networks, in order to provide an impetus for further studies on middle powers in Asia. Frances Antoinette C. Cruz University of the Philippines Diliman 1. Middle Powers: Beyond capability? From a question of physical properties or geographical location, the definition of middle powers has been contested due to conceptual ambiguity and their relevance in the exercise of global affairs vis-à-vis great powers. -

Interdisciplinary Minors

03-05 GEN ID Minors 253-257 9/30/03 1:51 PM Page 253 (Black plate) 2 0 3 - 5 Students should consult the General/Graduate Catalog INTERDISCIPLINARY and advisors concerning course credits available through MINORS Study Abroad, in Africa and possibly elsewhere. Students are encouraged to pursue study in an academic Additions or substitutions must be approved by the minor to provide contrasting and parallel study to the African/African-American Studies Committee and the Vice major. Serving to complement the major and help students President for Academic Affairs. further expand and integrate knowledge, academic minors are offered in a variety of disciplinary and interdisciplinary ASIAN STUDIES subjects. Students who choose to pursue minors should Home Division: Social Science seek advice from faculty members in their minor disciplines Students choosing this interdisciplinary minor have three as well as from their advisors in their major program. options. Those whose primary interest is in East Asia must satisfy Option I. Those interested primarily in South or Minimum requirements for all Academic Minor Pan-Asian topics must choose Option II. Those interested Programs: mainly in Asian American issues will choose Option III. 1. A minimum GPA of 2.0 for all coursework within the Students may double-count two courses toward their major or toward a second minor. With the approval of the Academic Minor Program. Interdisciplinary 2. A minimum of nine credit hours of the coursework for committee, courses taken in International Studies Academic Minor Programs must be taken through Exchange or Study Abroad Programs in Asian regions can Minors Truman State University, unless the discipline specifies a be substituted for courses below. -

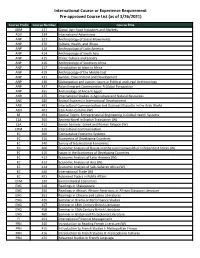

International Course Or Experience Requirement Pre-Approved Course List (As of 3/26/2021)

International Course or Experience Requirement Pre-approved Course List (as of 3/26/2021) Course Prefix Course Number Course Title ABM 427 Global Agri-Food Industries and Markets ADV 334 International Advertising ANP 321 Anthropology of Social Movements ANP 370 Culture, Health, and Illness ANP 410 Anthropology of Latin America ANP 414 Anthropology of South Asia ANP 415 China: Culture and Society ANP 416 Anthropology of Southern Africa ANP 417 Introduction to Islam in Africa ANP 419 Anthropology of the Middle East ANP 431 Gender, Environment and Development ANP 436 Globalization and Justice: Issues in Political and Legal Anthropology ANP 437 Asian Emigrant Communities: A Global Perspective ANP 455 Archaeology of Ancient Egypt ANR 475 International Studies in Agriculture and Natural Resources ANS 480 Animal Systems in International Development ARB 491 Intercultural Communication and Business Etiquette in the Arab World ASN 401 East Asian Cultures (W) BE 491 Special Topics: Entrepreneurial Engineering in Global Health Systems CLA 360 Ancient Novel in English Translation (W) CLA 412 Senior Seminar: Greek and Roman Religion (W) COM 310 Intercultural Communication EC 306 Comparative Economic Systems EC 310 Economics of Developing Countries EC 340 Survey of International Economics EC 406 Economic Analysis of Russia and the Commonwealth of Independent States (W) EC 410 Issues in the Economics of Developing Countries EC 412 Economic Analysis of Latin America (W) EC 413 Economic Analysis of Asia (W) EC 414 Economic Analysis of Sub–Saharan Africa -

Class of 2024 Department Catalog And

Class of 2024 Department Catalog and Guide to Academic Programs Department of Geography and - 0 – Environmental Engineering - 2 - DEPARTMENT CATALOG GUIDE TO THE ACADEMIC PROGRAMS CLASS OF 2024 TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS .............................................................................. 1 MESSAGE TO CADETS ............................................................................... 3 AFTER GRADUATION ................................................................................ 6 ACADEMIC AWARDS - PREVIOUS AWARDEES ................................... 10 CENTERS FOR ACADEMIC EXCELLENCE ........................................... 11 PROGRAMS FOR THE CLASS OF 2024 .................................................... 14 ACADEMIC MAJOR DESCRIPTIONS ..................................................... 15 GEOGRAPHY ............................................................................................. 17 GEOGRAPHY MINOR ............................................................................... 21 HUMAN GEOGRAPHY COMPLEMENTARY SUPPORT COURSES ... 22 HUMAN GEOGRAPHY COMPLEMENTARY SUPPORT COURSES ... 26 PHYSICAL GEOGRAPHY COMPLEMENTARY SUPPORT COURSES 27 ENVIRONMENTAL SCIENCE ................................................................ 28 ENVIRONMENTAL ENGINEERING..................................................... 32 GEOSPATIAL INFORMATION SCIENCE .............................................. 35 ACADEMIC COUNSELORS FOR AY 20-21 .............................................. 38 COURSE DIRECTORS FOR AY -

Adam Krikorian– Head Coach • 9Th Year • UCLA ('97)

Adam Krikorian – Head Coach • 9th Year • UCLA (‘97) There may not be another head coach in any a third-place finish in the MPSF Tournament and sport throughout the country who has accomplished a No. 3 final national ranking. For the first time in more than Adam Krikorian in such a short span. In program history, the Bruins won four games against his 16 years with UCLA’s water polo program as conference-rival Stanford. In the spring of 2007, both a player and a coach, Krikorian has won an Krikorian guided the women’s team to its third unprecedented 13 national titles – nine as a head consecutive NCAA title and UCLA’s 100th NCAA coach, three as an assistant coach and one as a team championship. The 2007 women’s water polo student-athlete. title marked Krikorian’s fourth national championship This fall, Adam Krikorian enters his ninth season since the start of the 2004-05 school year. as head coach of the UCLA men’s water polo team That season, Krikorian led both water polo teams and his seventh season alone at the helm. In 1999 to national-champion status for the third time in and 2000, he shared head coaching duties with his head coaching career. Krikorian previously led Guy Baker, who now serves as head coach of the both squads to national championships in the same U.S. Women’s National Team. season in 1999-2000 and 2000-01. The 2004 men’s As the men’s water polo head coach, Krikorian water polo team finished with the best winning per- has guided UCLA to three NCAA Championships centage of any UCLA water polo team since 1972, and boasts a .767 winning percentage (155-47 and the 2005 women’s team completed the second record). -

WEEK 11 — TRIP to the DESERT Match 26 • Arizona State • Friday, Nov

Oregon State Athletic Communications • Volleyball Contact: Melody Stockwell [email protected] • 541-737-3720 — Office • 541-737-3072 — Fax 2010 VOLLEYBALL SCHEDULE WEEK 11 — TRIP TO THE DESERT Match 26 • Arizona State • Friday, Nov. 5 • 7:00 p.m. • Wells Fargo Arena DATE OPPONENT TIME/RESULT 08.21 Orange & Black Scrimmage 11:30 a.m. All-Time Series: 16-34 Radio: None 08.27 Portland! L, 1-3 Current Streak: Arizona State W2 TV: None 08.28 Sacramento State! L, 2-3 Last Meeting: October 9, 2010 Gametracker: thesundevils.com 08.28 Illinois State! L, 1-3 Current Ranking: N/A Live Video: None 08.31 Portland State W, 3-2 09.03 Florida Gulf Coast@ W, 3-0 Match 27 • Arizona • Saturday, Nov. 6 • 7:00 p.m. • McKale Center 09.04 UNLV@ W, 3-1 All-Time Series: 13-37 Radio: None 09.04 No. 19 Michigan@ L, 1-3 Current Streak: Arizona W1 TV: None 09.10 Auburn# L, 0-3 Last Meeting: October 8, 2010 Gametracker: arizonaathletics.com 09.11 Cincinnati# W, 3-1 Current Ranking: 23rd Live Video: arizonaathletics.com 09.11 College of Charleston# W, 3-2 09.15 Seattle W, 3-2 LOOKING AHEAD — Oregon State (8-17, 1-10 MATCH 27: NO. 23 ARIZONA — Saturday, 09.17 Cal Poly$ L, 2-3 Pac-10) heads to the desert to face the Arizona Nov. 6 (7:00 p.m.): Oregon State is 13-37 all-time 09.17 UC Davis$ L, 1-3 schools. The Beavers take on Arizona State (10- against the Wildcats. -

Jumping Scale in Southeast Asia

Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 2002, volume 20, pages 647 ^ 668 DOI:10.1068/d16s Geographies of knowing, geographies of ignorance: jumping scale in Southeast Asia Willem van Schendelô Asia Studies in Amsterdam, University of Amsterdam, Oudezijds Achterburgwal 237, 1012 DL Amsterdam, The Netherlands; e-mail: [email protected] Received 6 February 2002; in revised form 27 March 2002 Abstract. `Area studies' use a geographical metaphor to visualise and naturalise particular social spaces as well as a particular scale of analysis. They produce specific geographies of knowing but also create geographies of ignorance. Taking Southeast Asia as an example, in this paper I explore how areas are imagined and how area knowledge is structured to construct area `heartlands' as well as area `border- lands'. This is illustrated by considering a large region of Asia (here named Zomia) that did not make it as a world area in the area dispensation after World War 2 because it lacked strong centres of state formation, was politically ambiguous, and did not command sufficient scholarly clout. As Zomia was quartered and rendered peripheral by the emergence of strong communities of area specialists of East, Southeast, South, and Central Asia, the production of knowledge about it slowed down. I suggest that we need to examine more closely the academic politics of scale that create and sustain area studies, at a time when the spatialisation of social theory enters a new, uncharted terrain. The heuristic impulse behind imagining areas, and the high-quality, contextualised knowledge that area studies produce, may be harnessed to imagine other spatial configurations, such as `crosscutting' areas, the worldwide honeycomb of borderlands, or the process geographies of transnational flows. -

Soquel High School 2020-2021

SOQUEL HIGH SCHOOL 2020-2021 New Parent/Guardian Night Noche para Nuevos Padres Welcome Bienvenida Principal/Director ● Greg O’Meara ● 831.429-3909 x 123 ● [email protected] Kelly Moker, Assistant to Principal ([email protected]) 831.429.3909 x124 Asst. Principal of Student Services/Subdirector de Servicios Estudiantiles ● Jose Quevedo ● 831.429-3918 x 126 ● [email protected] Asst Principal of Counseling/Subdirector de Asesoramiento ● Derek Kendall ● 831.429-3909 x 125 ● [email protected] Webinar Format Only “Panelists are seen/heard Please do not use “raise hand” feature Please use Q/A Function and we will do our best to answer in this forum. Video recording, along with Q/A record will be available on School Website Soquel High School - Home of the Knights MISSION Educate - Engage - Empower VISION Soquel High is a diverse, creative, and professional learning community that encourages and supports all Knights to achieve intellectual and personal excellence, and to be prepared for college, career, and society. VALUES ● Kindness ● Responsibility ● Safety ● Collaboration ● Equity ● Diversity ● Integrity Athletics Atletismo Athletic Director/Director de Atletismo ● Stu Walters ● [email protected] Season 1 (Dec/Jan) Season 2 Cross Country (Men/Women) Tennis (Men/Women) (2/22) (Men/Women) Baseball/Softball (3/15) Football Soccer (Men/Women)(2/22) Water Polo (Men/Women) Wrestling(3/15) Volleyball (Men/Women) Basketball (Men/Women) (3/15) Cheer Swimming (Men/Women) (3/8) Track and Field (3/15) Lacrosse (3/15) Cheer (3/15) Requirement for Athletic Participation ● Current Physical Exam on File ● Paperwork available on school website ● Must maintain at least a 2.0 gpa (monitored every 6 weeks) Accessing Student Schedules, Email, and Chromebooks Access the Soquel High website Soquel High School: Home Upper Right Corner locate Parent Portal and Student Email For Parent Portal enter login credentials you used when registering your child ◻ Schedules ◻ Attendance/Asistencia ◻ Grades/Calificaciones ◻ Homework, participation, tests & quizzes, etc. -

Geography of Asia Syllabus, Spring 2014

Geography 322: Geography of Asia Syllabus, Spring 2014 Dr. Wolfgang Hoeschele Professor of Geography Office: Barnett 2205 Office phone: 785-4032 E-mail: [email protected] Office hours: Monday through Thursday 10:30-12; Friday 10:30-11 (please note that it is best to make appointments in advance, because I often make international Skype calls during this time) or by appointment (TuTh 1:30-3, MW 3-4 are usually good options) Purpose This course is designed as an introduction to the human geography of Asia, considering such topics as political/economic geography, urban geography, agricultural geography, environmental geography, and the geography of ethnicity. Asia, an entity which might better be referred to in the plural as “the Asias,” includes such diverse cultural regions as East Asia, Southeast Asia, South Asia, Southwest Asia (the “Middle East”) and Central Asia. More than 50% of all humans live in Asia. Since complete coverage of all these regions and peoples is simply not possible in a single course, my aim is to examine various topics of contemporary relevance, with consideration of cases in South, Southeast and East Asia (a region some people refer to as “monsoon Asia”). A particular concern is to study the contestation of place, i.e. human conflicts over how places are to develop into the future, and the outcomes of these conflicts. Class sessions will be devoted to a combination of lecture and discussion. Lecture content is designed to provide broad introductions to major topics, and to provide context for specific readings. The discussions will be based on readings, mostly consisting of journal articles and book chapters. -

2007 Panther Football Media Guide

University of Northern Iowa UNI ScholarWorks Athletics Media Guides Athletics 2007 2007 Panther Football Media Guide University of Northern Iowa Let us know how access to this document benefits ouy Copyright ©2007 Athletics, University of Northern Iowa Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uni.edu/amg Part of the Higher Education Commons Recommended Citation University of Northern Iowa, "2007 Panther Football Media Guide" (2007). Athletics Media Guides. 260. https://scholarworks.uni.edu/amg/260 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Athletics at UNI ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Athletics Media Guides by an authorized administrator of UNI ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. UNI in the FARLEY ERA The BEST of the BEST • Three Top-5 FCS national rankings, five Top 25 rankings overall • UNI has competed in three playoffs, advancing to national title game in 2005 • Steady climb in home attendance, culminating in 2005 with the 12th highest average in FCS • The Panthers have had one Gateway Football Conference Defensive Player of the Year, two GFC Newcomers of the Year, one GFC Freshman of the Year, and head coach Mark Farley has received one league Coach of the Year honor • UNI has had 23 first team all-conference honorees since 2001 • Thirty Panthers have been named to conference All-Academic teams since Coach Farley’s arrival, nine to various academic all-star teams • Forty-nine players have received league Player of the Week honors since 2001