Working Paper Series

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 2001-2003 CATALOG UPDATE Changes Effective 2002-2003

2001-2003 CATALOG UPDATE Changes effective 2002-2003 ASIAN STUDIES MINOR Students choosing this interdisciplinary minor have three options. Those whose primary interest is in East Asia must satisfy Option I. Those interested primarily in south or Pan-Asian topics must choose Option II. Those interested mainly in Asian American issues will choose Option III. Students may double-count two courses toward their major or toward a second minor. With the approval of the committee, courses taken in International Studies Exchange or Study Abroad Programs in Asian regions can be substituted for courses below. OPTION I East Asian Worksheet The East Asian Option requires successful completion of 18 hours of courses listed below: Intermediate proficiency in either Chinese or Japanese is mandatory. CHIN 212 Intermediate Chinese I CHIN 213 Intermediate Chinese II JAPN 201 Intermediate Japanese I JAPN 202 Intermediate Japanese II (total of 6 hours) Select the remaining 12 hours from the three areas listed below. Students must have at least one course from each of the three areas listed below. At least two courses should be at or above the 300-level. Area I LLFL 429 Studies in Chinese: 3rd Year I LLFL 429 Studies in Chinese: 3rd Year II JAPN 301 Advanced Japanese I JAPN 302 Advanced Japanese II ENG 225 World Literatures: Chronology—Anytime, Asia ENG 307 Twentieth Century World Literature—Asia ENG 320 Asian Literature ENG 322 Studies in World Cinema—Asia FREN 401 Francophone Indochinese Literature Area II HIST 141 East Asian Civilization I HIST 142 East Asian Civilization II HIST 434 History of Japan I HIST 435 History of Japan II HIST 448 History of China I HIST 449 History of China II GEOG 322 Geography of Asia Area III PHRE 347 Studies in Religion II—the Hindu, Buddhist, Japanese, Taoist, Yoga, or Chinese Traditions PHRE 362 Women in Buddhism PHRE 363 Women in Chinese Religion CHIN 311 Chinese Culture 1 OPTION II South or Pan-Asian Worksheet The South or Pan-Asian Option requires successful completion of at least 15 hours taken from the courses listed below. -

Interdisciplinary Minors

03-05 GEN ID Minors 253-257 9/30/03 1:51 PM Page 253 (Black plate) 2 0 3 - 5 Students should consult the General/Graduate Catalog INTERDISCIPLINARY and advisors concerning course credits available through MINORS Study Abroad, in Africa and possibly elsewhere. Students are encouraged to pursue study in an academic Additions or substitutions must be approved by the minor to provide contrasting and parallel study to the African/African-American Studies Committee and the Vice major. Serving to complement the major and help students President for Academic Affairs. further expand and integrate knowledge, academic minors are offered in a variety of disciplinary and interdisciplinary ASIAN STUDIES subjects. Students who choose to pursue minors should Home Division: Social Science seek advice from faculty members in their minor disciplines Students choosing this interdisciplinary minor have three as well as from their advisors in their major program. options. Those whose primary interest is in East Asia must satisfy Option I. Those interested primarily in South or Minimum requirements for all Academic Minor Pan-Asian topics must choose Option II. Those interested Programs: mainly in Asian American issues will choose Option III. 1. A minimum GPA of 2.0 for all coursework within the Students may double-count two courses toward their major or toward a second minor. With the approval of the Academic Minor Program. Interdisciplinary 2. A minimum of nine credit hours of the coursework for committee, courses taken in International Studies Academic Minor Programs must be taken through Exchange or Study Abroad Programs in Asian regions can Minors Truman State University, unless the discipline specifies a be substituted for courses below. -

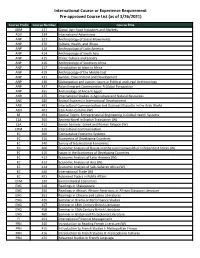

International Course Or Experience Requirement Pre-Approved Course List (As of 3/26/2021)

International Course or Experience Requirement Pre-approved Course List (as of 3/26/2021) Course Prefix Course Number Course Title ABM 427 Global Agri-Food Industries and Markets ADV 334 International Advertising ANP 321 Anthropology of Social Movements ANP 370 Culture, Health, and Illness ANP 410 Anthropology of Latin America ANP 414 Anthropology of South Asia ANP 415 China: Culture and Society ANP 416 Anthropology of Southern Africa ANP 417 Introduction to Islam in Africa ANP 419 Anthropology of the Middle East ANP 431 Gender, Environment and Development ANP 436 Globalization and Justice: Issues in Political and Legal Anthropology ANP 437 Asian Emigrant Communities: A Global Perspective ANP 455 Archaeology of Ancient Egypt ANR 475 International Studies in Agriculture and Natural Resources ANS 480 Animal Systems in International Development ARB 491 Intercultural Communication and Business Etiquette in the Arab World ASN 401 East Asian Cultures (W) BE 491 Special Topics: Entrepreneurial Engineering in Global Health Systems CLA 360 Ancient Novel in English Translation (W) CLA 412 Senior Seminar: Greek and Roman Religion (W) COM 310 Intercultural Communication EC 306 Comparative Economic Systems EC 310 Economics of Developing Countries EC 340 Survey of International Economics EC 406 Economic Analysis of Russia and the Commonwealth of Independent States (W) EC 410 Issues in the Economics of Developing Countries EC 412 Economic Analysis of Latin America (W) EC 413 Economic Analysis of Asia (W) EC 414 Economic Analysis of Sub–Saharan Africa -

Class of 2024 Department Catalog And

Class of 2024 Department Catalog and Guide to Academic Programs Department of Geography and - 0 – Environmental Engineering - 2 - DEPARTMENT CATALOG GUIDE TO THE ACADEMIC PROGRAMS CLASS OF 2024 TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS .............................................................................. 1 MESSAGE TO CADETS ............................................................................... 3 AFTER GRADUATION ................................................................................ 6 ACADEMIC AWARDS - PREVIOUS AWARDEES ................................... 10 CENTERS FOR ACADEMIC EXCELLENCE ........................................... 11 PROGRAMS FOR THE CLASS OF 2024 .................................................... 14 ACADEMIC MAJOR DESCRIPTIONS ..................................................... 15 GEOGRAPHY ............................................................................................. 17 GEOGRAPHY MINOR ............................................................................... 21 HUMAN GEOGRAPHY COMPLEMENTARY SUPPORT COURSES ... 22 HUMAN GEOGRAPHY COMPLEMENTARY SUPPORT COURSES ... 26 PHYSICAL GEOGRAPHY COMPLEMENTARY SUPPORT COURSES 27 ENVIRONMENTAL SCIENCE ................................................................ 28 ENVIRONMENTAL ENGINEERING..................................................... 32 GEOSPATIAL INFORMATION SCIENCE .............................................. 35 ACADEMIC COUNSELORS FOR AY 20-21 .............................................. 38 COURSE DIRECTORS FOR AY -

Jumping Scale in Southeast Asia

Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 2002, volume 20, pages 647 ^ 668 DOI:10.1068/d16s Geographies of knowing, geographies of ignorance: jumping scale in Southeast Asia Willem van Schendelô Asia Studies in Amsterdam, University of Amsterdam, Oudezijds Achterburgwal 237, 1012 DL Amsterdam, The Netherlands; e-mail: [email protected] Received 6 February 2002; in revised form 27 March 2002 Abstract. `Area studies' use a geographical metaphor to visualise and naturalise particular social spaces as well as a particular scale of analysis. They produce specific geographies of knowing but also create geographies of ignorance. Taking Southeast Asia as an example, in this paper I explore how areas are imagined and how area knowledge is structured to construct area `heartlands' as well as area `border- lands'. This is illustrated by considering a large region of Asia (here named Zomia) that did not make it as a world area in the area dispensation after World War 2 because it lacked strong centres of state formation, was politically ambiguous, and did not command sufficient scholarly clout. As Zomia was quartered and rendered peripheral by the emergence of strong communities of area specialists of East, Southeast, South, and Central Asia, the production of knowledge about it slowed down. I suggest that we need to examine more closely the academic politics of scale that create and sustain area studies, at a time when the spatialisation of social theory enters a new, uncharted terrain. The heuristic impulse behind imagining areas, and the high-quality, contextualised knowledge that area studies produce, may be harnessed to imagine other spatial configurations, such as `crosscutting' areas, the worldwide honeycomb of borderlands, or the process geographies of transnational flows. -

Geography of Asia Syllabus, Spring 2014

Geography 322: Geography of Asia Syllabus, Spring 2014 Dr. Wolfgang Hoeschele Professor of Geography Office: Barnett 2205 Office phone: 785-4032 E-mail: [email protected] Office hours: Monday through Thursday 10:30-12; Friday 10:30-11 (please note that it is best to make appointments in advance, because I often make international Skype calls during this time) or by appointment (TuTh 1:30-3, MW 3-4 are usually good options) Purpose This course is designed as an introduction to the human geography of Asia, considering such topics as political/economic geography, urban geography, agricultural geography, environmental geography, and the geography of ethnicity. Asia, an entity which might better be referred to in the plural as “the Asias,” includes such diverse cultural regions as East Asia, Southeast Asia, South Asia, Southwest Asia (the “Middle East”) and Central Asia. More than 50% of all humans live in Asia. Since complete coverage of all these regions and peoples is simply not possible in a single course, my aim is to examine various topics of contemporary relevance, with consideration of cases in South, Southeast and East Asia (a region some people refer to as “monsoon Asia”). A particular concern is to study the contestation of place, i.e. human conflicts over how places are to develop into the future, and the outcomes of these conflicts. Class sessions will be devoted to a combination of lecture and discussion. Lecture content is designed to provide broad introductions to major topics, and to provide context for specific readings. The discussions will be based on readings, mostly consisting of journal articles and book chapters. -

Class of 2022

Department Catalog and Guide to Academic Programs Class of 2022 Department of Geography and Environmental Engineering - 0 – DEPARTMENT CATALOG GUIDE TO THE ACADEMIC PROGRAMS CLASS OF 2022 TABLE OF CONTENTS Message to Cadets ............................................................................................................... 2 After Graduation ................................................................................................................. 5 Department Opportunities .............................................................................................. 7 Center for Academic Excellence ................................................................................... 10 Programs for Class of 2022 ............................................................................................. 11 Academic Major Descriptions ........................................................................................ 12 Academic Major Details.................................................................................................... 14 Faculty Counselors ........................................................................................................... 30 Course Offerings and Descriptions ................................................................................ 32 Complementary Support Courses ................................................................................... 45 Department Faculty .......................................................................................................... -

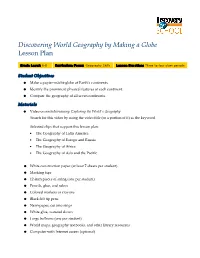

Discovering World Geography by Making a Globe Lesson Plan

Discovering World Geography by Making a Globe Lesson Plan Grade Level: 6-8 Curriculum Focus: Geography Skills Lesson Duration: Three to four class periods Student Objectives Make a papier-mâché globe of Earth’s continents. Identify the prominent physical features of each continent. Compare the geography of all seven continents. Materials Video on unitedstreaming: Exploring the World's Geography Search for this video by using the video title (or a portion of it) as the keyword. Selected clips that support this lesson plan: The Geography of Latin America The Geography of Europe and Russia The Geography of Africa The Geography of Asia and the Pacific White construction paper (at least 7 sheets per student) Masking tape 12-inch pieces of string (one per student) Pencils, glue, and rulers Colored markers or crayons Black felt tip pens Newspaper, cut into strips White glue, watered down Large balloons (one per student) World maps, geography textbooks, and other library resources Computer with Internet access (optional) Discovering World Geography by Making a Globe 2 Lesson Plan: Procedures 1. Begin the lesson by discussing the diverse geography of Earth’s seven continents. A good way to introduce this topic is to show segments of the program World Geography. After watching, ask students these questions: How is Europe different from Asia? Where is South America located? Where are the Andes? Is North America the largest continent? Also, have them describe the pampas, taiga, or other geographic features. 2. Using a globe, point out the equator and the prime meridian. Ask students which continents are below the equator and which continents are above it. -

Russia / (South and East Asia) Southeast Asia Essential Questions

World Cultures Humble ISD Bundle Two-At-A-Glance Timeframe: 8 weeks Unit Name: Russia / (South and East Asia) Southeast Asia Essential Questions: How did communism develop and how does it continue to influence different world societies? How are various countries’ economies developed and how do they compare and contrast to one another? How did the actions of the czars lead to the acceptance of communism? How have geographic factors such as location, physical features, transportation corridors and barriers, and distribution of natural resources influenced societies in the region? What has been the influence of colonization, colonialism, and communism on the societies in the region? What influence has religion had on culture and life in Asia? What accounts for the wide differences between government and economic systems in Asia? How has the location and physical geography of Asia impacted how the people in this region live? Learning Outcomes: The student is expected to: Compare life expectancy, literacy rate, and GDP of Russia to Great Britain. Identify the Ural Mountains as the dividing line between Europe and Asia. Describe the differences in Russia’s climate and economy of each side of the Ural Mountains. Define and evaluate the characteristics of czars in the development of Russia. Identify Mikail Gorbachev as the last communist leader of the USSR who introduced his policies of glastnost and perestroika, and Boris Yeltsin as the first leader of the Republic of Russia after the fall of the communist Soviet Union. Identify Russia today as a federal republic like the United States. Discuss how the transition from communism to a free enterprise system has affected the economic and political issues of Russia today. -

Journey Into Asia

ASIA JOURNEY INTO ASIA RECOMMENDED GRADES: K-4 TIME NEEDED: 15-20 MINUTES Description Students explore the map of Asia and learn about colors featured on the map. Learning Objectives Materials Students will: • Classroom globe, inflatable globe, or a flat • learn about the size and diversity of the world map Asian continent • Colored cones (3) (optional) • be introduced to physical features on • Rope (long enough for all students in the the map class to hold) Preparation 2 minutes • Read over the activity and choose the items you want to emphasize. Add items of your own that relate to your students’ prior knowledge. • Place colored cones on the North Pole, Mount Everest, and the Dead Sea. Rules Have students remove shoes before walking on the map. DIRECTIONS 1. Begin by directing students to stand along the left border of the map so they are closest to Africa, looking inward toward the Asian continent. Introduce students to the giant map. Suggested introduction by teacher: PAGE 1 • NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC GIANT MAPS JOURNEY INTO ASIA Welcome to Asia! Today you are going to explore this amazing place. You will stand on the highest point in the world! You will stand on the lowest point in the world. You will walk thousands of miles. You are going to be warm and sweaty in the tropics and freezing cold in the Arctic. You will play games, have fun, and learn a whole lot about Asia! Give students two minutes to explore the continent on their own. This is an independent exploration, giving them the opportunity to walk around on the map before the structured activity that follows. -

Archaeology of the Silk Roads 2019-2020 MA MODULE HANDBOOK: 15 Credits Deadlines for Coursework for This Module: 6 March 2020 & 1 May 2020

UCL INSTITUTE OF ARCHAEOLOGY UCL INSTITUTE OF ARCHAEOLOGY ARCL0210: Archaeology of the Silk Roads 2019-2020 MA MODULE HANDBOOK: 15 credits Deadlines for coursework for this module: 6 March 2020 & 1 May 2020 Co-ordinator: Tim Williams [email protected] Room 602 Tel: 020 7679 4722 CONTENTS 1 Overview ......................................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Short description ....................................................................................................... 1 1.2 Timetable: Week-by-week summary ........................................................................ 1 1.2.1 Film night (optional) ......................................................................................... 2 1.2.2 Other events of interest ..................................................................................... 2 1.3 Basic introductory texts ............................................................................................ 2 1.4 Methods of assessment ............................................................................................. 2 1.5 Teaching methods ..................................................................................................... 2 1.6 Workload .................................................................................................................. 3 1.7 Prerequisites ............................................................................................................. 3 2 Aims, objectives and -

Download, but It Is Well Worth the Wait for Middle School Teachers Who Would Like a Photo/Graphics Presentation of the Geography of Japan for Their Students

RESOURCES WEB GLEANINGS By Judith S. Ames Teaching the Geographies of Asia Asia Japan Teaching Module URL: http://continents.pppst.com/asia.html URL: http://www.utc.edu/Research/AsiaProgram/teaching/ This site is excellent in many ways: the content, the concepts, the organization, and the photography. The geography portions consist of two main sections: Japanese Cultural Landscapes and Centripetal Forces in Japan; each section has five parts. The main page for each of the two sections shows the five parts’ first lines plus a photograph. Students will learn a lot here. The Geography of Japan URL: http://www.fcceastudytours.org/pdfs/GeographyJapan&Korea.pdf This 11.54 MB file (in PDF) takes a while to download, but it is well worth the wait for middle school teachers who would like a photo/graphics presentation of the geography of Japan for their students. One can keep busy for days simply exploring the links on this site. For the most Teaching about Japan: Geography part, these are links to PowerPoint presentations by teachers. Some presenta- URL: http://www.international.ucla.edu/eas/japan/geography/geo1.htm tions are more detailed than others. The links are grouped by geographic region This is an overview of the geography of Japan. The presentation is very attrac- in Asia: Southeast Asia, South Asia, East Asia, etc., and by Asian country. tive and easy to use. There are many helpful graphics and photographs. None of the sections provides deep insights, but there is enough basic information for HowStuffWorks: Geography of Asia a student new to the study of Japan.