Urban Voting and Party Choices in Delhi Matching Electoral Data with Property Category

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Life-Members

Life Members SUPREME COURT BAR ASSOCIATION Name & Address Name & Address 1 Abdul Mashkoor Khan 4 Adhimoolam,Venkataraman Membership no: A-00248 Membership no: A-00456 Res: Apartment No.202, Tower No.4,, SCBA Noida Res: "Prashanth", D-17, G.K. Enclave-I, New Delhi Project Complex, Sector - 99,, Noida 201303 110048 Tel: 09810857589 Tel: 011-26241780,41630065 Res: 328,Khan Medical Complex,Khair Nagar Fax: 41630065 Gate,Meerut,250002 Off: D-17, G.K. Enclave-I, New Delhi 110048 Tel: 0120-2423711 Tel: 011-26241780,41630065 Off: Apartment No.202, Tower No.4,, SCBA Noida Ch: 104,Lawyers Chamber, A.K.Sen Block, Supreme Project Complex, Sector - 99,, Noida 201303 Court of India, New Delhi 110001 Tel: 09810857589 Mobile: 9958922622 Mobile: 09412831926 Email: [email protected] 2 Abhay Kumar 5 Aditya Kumar Membership no: A-00530 Membership no: A-00412 Res: H.No.1/12, III Floor,, Roop Nagar,, Delhi Res: C-180,, Defence Colony, New Delhi 110024 110007 Off: C-13, LGF, Jungpura, New Delhi 110014 Tel: 24330307,24330308 41552772,65056036 Tel: 011-24372882 Tel: 095,Lawyers Chamber, Supreme Court of India, Ch: 104, Lawyers Chamber, Supreme Court of India, Ch: New Delhi 110001 New Delhi 110001 23782257 Mobile: 09810254016,09310254016 Tel: Mobile: 9911260001 Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] 3 Abhigya 6 Aganpal,Pooja (Mrs.) Membership no: A-00448 Membership no: A-00422 Res: D-228, Nirman Vihar, Vikas Marg, Delhi 110092 Res: 4/401, Aganpal Chowk, Mehrauli, New Delhi Tel: 22432839 110030 Off: 704,Lawyers Chamber, Western Wing, Tis Hazari -

Government Cvcs for Covid Vaccination for 18 Years+ Population

S.No. District Name CVC Name 1 Central Delhi Anglo Arabic SeniorAjmeri Gate 2 Central Delhi Aruna Asaf Ali Hospital DH 3 Central Delhi Balak Ram Hospital 4 Central Delhi Burari Hospital 5 Central Delhi CGHS CG Road PHC 6 Central Delhi CGHS Dev Nagar PHC 7 Central Delhi CGHS Dispensary Minto Road PHC 8 Central Delhi CGHS Dispensary Subzi Mandi 9 Central Delhi CGHS Paharganj PHC 10 Central Delhi CGHS Pusa Road PHC 11 Central Delhi Dr. N.C. Joshi Hospital 12 Central Delhi ESI Chuna Mandi Paharganj PHC 13 Central Delhi ESI Dispensary Shastri Nagar 14 Central Delhi G.B.Pant Hospital DH 15 Central Delhi GBSSS KAMLA MARKET 16 Central Delhi GBSSS Ramjas Lane Karol Bagh 17 Central Delhi GBSSS SHAKTI NAGAR 18 Central Delhi GGSS DEPUTY GANJ 19 Central Delhi Girdhari Lal 20 Central Delhi GSBV BURARI 21 Central Delhi Hindu Rao Hosl DH 22 Central Delhi Kasturba Hospital DH 23 Central Delhi Lady Reading Health School PHC 24 Central Delhi Lala Duli Chand Polyclinic 25 Central Delhi LNJP Hospital DH 26 Central Delhi MAIDS 27 Central Delhi MAMC 28 Central Delhi MCD PRI. SCHOOl TRUKMAAN GATE 29 Central Delhi MCD SCHOOL ARUNA NAGAR 30 Central Delhi MCW Bagh Kare Khan PHC 31 Central Delhi MCW Burari PHC 32 Central Delhi MCW Ghanta Ghar PHC 33 Central Delhi MCW Kanchan Puri PHC 34 Central Delhi MCW Nabi Karim PHC 35 Central Delhi MCW Old Rajinder Nagar PHC 36 Central Delhi MH Kamla Nehru CHC 37 Central Delhi MH Shakti Nagar CHC 38 Central Delhi NIGAM PRATIBHA V KAMLA NAGAR 39 Central Delhi Polyclinic Timarpur PHC 40 Central Delhi S.S Jain KP Chandani Chowk 41 Central Delhi S.S.V Burari Polyclinic 42 Central Delhi SalwanSr Sec Sch. -

Dr.B.C.Rathore Cause List

011-28031838 011-28032406 Fax no. 28032381 Patents/Designs/Trademark GEOGRAPHICAL INDICATIONS GOVERNMENT OF INDIA MINISTRY OF COMMERCE & INDUSTRY Plot No.32, Sector – 14, Dwarka NEW DELHI - 110078. Name of Hearing Officer: DR.B.C.RATHORE (JOINT REGISTRAR) Date: 01/08/2019 Time: 11:00 AM. CAUSE LIST S.No OPPOSITION APPLICATION NAME OF PARTIES NAME OF REPRESENTATIVE. NO. NO. 1 174531 1091937 M/S EASTERN MEDIKIT LIMITED M/S MADAMSER & CO N - 22, GREATER KAILASH, PART - 1, FLATNO.E(G.F) SAGAR APARTMENTS, NEW DELHI - 48. 6, TILAK MARG, V/S NEW DELHI-110001. M/S ROMSONS SCIENTIFIC & SURGICAL V/S IND. PVT. LTD. M/S P.K.ARORA 63, INDL. ESTATE,NUNHAI, 110, ANAND VRINDAVAN AGRA SANJAY PALACE AGRA-02 (U.P.) TM-5 TIME BARRED 2 191277 1122329 M/S FILEX SYSTEMS PRIVATE LIMITED, M/S MANGLA REGISTRATION SERVICE, 3/27, ROOP NAGAR, DELHI - 110 007. 1961, KATRA SHAHN-SHAHI, V/S CHANDNI CHOWK, DELHI-110006. M/S WM. WRIGLEY JR. CO. V/S 410 NORTH MICHIGAN AVENUE, CHICAGO, M/S ANAND AND ANAND, 1L 60611, USA. B-41, NIZAMUDDIN EAST, NEW DELHI-11013. 3 170889 1086061 M/S BLAZE VELVET & COSMETICS (INDIA). SHRI AMIT SACHDEVA WZ - 19, NEAR M. C. D. SCHOOL, VILLAGE SHOP NO.2904/04, RUI MANDI, DASGHARA, NEW DELHI - 110 012. HANUMAN MARKET, SADAR BAZAR V/S DELHI-110006 M/S J.R.PRODUCTS V/S 55, VITHALJINA PATEL CHAWL, OPP PARK M/S M.P. MIRCHANDANI SIDE HOTEL, M.G.ROAD, SUKHERWADI, RAM MANSION, IST FLOOR, ROOM NO.4, BORIVALI (E) MUMBAI-400066. -

LIST of ORDINARY MEMBERS S.No

LIST OF ORDINARY MEMBERS S.No. MemNo MName Address City_Location State PIN PhoneMob F - 42 , PREET VIHAR 1 A000010 VISHWA NATH AGGARWAL VIKAS MARG DELHI 110092 98100117950 2 A000032 AKASH LAL 1196, Sector-A, Pocket-B, VASANT KUNJ NEW DELHI 110070 9350872150 3 A000063 SATYA PARKASH ARORA 43, SIDDHARTA ENCLAVE MAHARANI BAGH NEW DELHI 110014 9810805137 4 A000066 AKHTIARI LAL S-435 FIRST FLOOR G K-II NEW DELHI 110048 9811046862 5 A000082 P.N. ARORA W-71 GREATER KAILASH-II NEW DELHI 110048 9810045651 6 A000088 RAMESH C. ANAND ANAND BHAWAN 5/20 WEST PATEL NAGAR NEW DELHI 110008 9811031076 7 A000098 PRAMOD ARORA A-12/2, 2ND FLOOR, RANA PRATAP BAGH DELHI 110007 9810015876 8 A000101 AMRIK SINGH A-99, BEHIND LAXMI BAI COLLEGE ASHOK VIHAR-III NEW DELHI 110052 9811066073 9 A000102 DHAN RAJ ARORA M/S D.R. ARORA & C0, 19-A ANSARI ROAD NEW DELHI 110002 9313592494 10 A000108 TARLOK SINGH ANAND C-21, SOUTH EXTENSION, PART II NEW DELHI 110049 9811093380 11 A000112 NARINDERJIT SINGH ANAND WZ-111 A, IInd FLOOR,GALI NO. 5 SHIV NAGAR NEW DELHI 110058 9899829719 12 A000118 VIJAY KUMAR AGGARWAL 2, CHURCH ROAD DELHI CANTONMENT NEW DELHI 110010 9818331115 13 A000122 ARUN KUMAR C-49, SECTOR-41 GAUTAM BUDH NAGAR NOIDA 201301 9873097311 14 A000123 RAMESH CHAND AGGARWAL B-306, NEW FRIENDS COLONY NEW DELHI 110025 989178293 15 A000126 ARVIND KISHORE 86 GOLF LINKS NEW DELHI 110003 9810418755 16 A000127 BHARAT KUMR AHLUWALIA B-136 SWASTHYA VIHAR, VIKAS MARG DELHI 110092 9818830138 17 A000132 MONA AGGARWAL 2 - CHURCH ROAD, DELHI CANTONMENT NEW DELHI 110010 9818331115 18 A000133 SUSHIL KUMAR AJMANI F-76 KIRTI NAGAR NEW DELHI 110015 9810128527 19 A000140 PRADIP KUMAR AGGARWAL DISCO COMPOUND, G.T. -

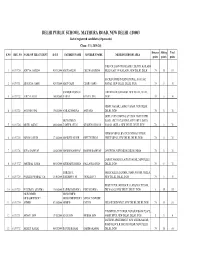

DELHI PUBLIC SCHOOL, MATHURA ROAD, NEW DELHI -110003 List of Registered Candidates (Open Seats) Class - VI ( 2019-20) Distance Sibling Total S.NO REG

DELHI PUBLIC SCHOOL, MATHURA ROAD, NEW DELHI -110003 List of registered candidates (Open seats) Class - VI ( 2019-20) Distance Sibling Total S.NO REG. NO NAME OF THE STUDENT D.O.B FATHER'S NAME MOTHER'S NAME NEIGHBOURHOOD AREA points points points C BLOCK EAST OF KAILASH, C BLOCK, KAILASH 1 6/19/3720 ADITYA SAXENA 03/09/2008 AMIT SAXENA CHETNA SAXENA HILLS, EAST OF KAILASH, NEW DELHI, DELHI 70 15 85 SACRED HOME INTERNATIONAL, GAUTAM 2 6/19/3721 SHAURYA GARG 02/07/2008 AMIT GARG CHARU GARG NAGAR, NEW DELHI, DELHI, INDIA 70 0 70 SHAMSHER SINGH LODHI ROAD, JOR BAGH, NEW DELHI, DELHI, 3 6/19/3722 ADITYA RAO 16/03/2009 YADAV KAVITA DEVI INDIA 70 0 70 NEHRU NAGAR, LAJPAT NAGAR, NEW DELHI, 4 6/19/3723 AAYUSHI RAI 19/05/2008 ANIL KUMAR RAI ANITA RAI DELHI, INDIA 70 0 70 OKHLA VIHAR METRO STATION, HARI KOTHI MOHAMMAD ROAD, ABUL FAZAL ENCLAVE PART 1, JAMIA 5 6/19/3724 MOHD ASHAZ 20/08/2008 ZAMEER AFZAL SHABRINA HASAN NAGAR, OKHLA, NEW DELHI, DELHI, INDIA 70 0 70 NIRMAN VIHAR, BLOCK D, NIRMAN VIHAR, 6 6/19/3725 ISHMAN SINGH 27/12/2008 MANDEEP SINGH PREETY REHAL PREET VIHAR, NEW DELHI, DELHI, INDIA 70 0 70 7 6/19/3726 DIVA KASHYAP 26/08/2008 MANISH KASHYAP RASHMI KASHYAP JANGPURA, NEW DELHI, DELHI, INDIA 70 0 70 LAJPAT NAGAR II, LAJPAT NAGAR, NEW DELHI, 8 6/19/ 3727 SARTHAK SINHA 06/08/2008 SIDDHARTH SINHA PALLAVEE SINHA DELHI, INDIA 70 0 70 HABEEBUL JAMIA MILLIA ISLAMIA, JAMIA NAGAR, OKHLA, 9 6/19/3728 NASEEM SWABAH V M 15/10/2008 RAHIMAN V M SWALIHA C A NEW DELHI, DELHI, INDIA 70 0 70 KESHAV PURAM, BLOCK C8, KESHAV PURAM, 10 6/19/3729 NAVDISHA -

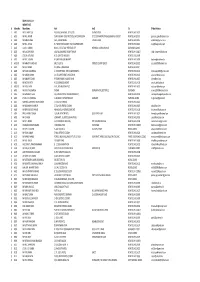

DELHI GOLF CLUB MEMBER LIST Sr Mem.No Mem.Name Add1 Add2 City E-Mail Address 1 A009 MR K

DELHI GOLF CLUB MEMBER LIST Sr Mem.No Mem.Name Add1 Add2 City E-Mail Address 1 A009 MR K. AMRIT LAL 90E, MALCHA MARG, IST FLOOR, CHANKYAPURI NEW DELHI 110021 2 A016 MR N.S. ATWAL GURU MEHAR CONSTRUCTION,S.M.COMPLEX,K-4 G.F.2,OLD RANGPURI ROAD,MAHIPAL PUR EXT. NEW DELHI-110037 [email protected] 3 A018 MR AMAR SINGH 16-A, PALAM MARG VASANT VIHAR, NEW DELHI 110057 [email protected] 4 A021 MR N.S. AHUJA B-7,WEST END COLONY, RAO TULARAM MARG NEW DELHI 110021 [email protected] 5 A022 COL K.C. ANAND BLOCK - 9,FLAT 302 HERITAGE CITY MEHRAULI GURGOAN ROAD GURGOAN 122002 6 A026 MR. ANOOP SINGH 16A, PALAM MARG VASANT VIHAR NEW DELHI- 110057 [email protected] 7 A028 LT GEN. AJIT SINGH R-51, GREATER KAILASH-I, NEW DELHI 110048 8 A032 MR M.T. ADVANI 6-SUNDER NAGAR MARKET, NEW DELHI 110003 [email protected] 9 A035 D1 MR AMARJIT SINGH (II) 680, C-BLOCK, FRIENDS COLONY (EAST) NEW DELHI-110025 [email protected] 10 A042 MR S.S. ANAND N-3,NDSE-1,RING ROAD, NEW DELHI-110049 11 A046 MR VIJAY AGGARWAL 2, CHURCH ROAD, DELHI CANTONMENT, NEW DELHI 110010 [email protected] 12 A051 MR ARJUN ASRANI 12, SFS APARTMENTS HAUZ KHAS NEW DELHI 110016 [email protected] 13 A056 MR AMARJIT SAHAY 9 POORVI MARG VASANT VIHAR NEW DELHI 110057 [email protected] 14 A058 MR ACHAL NATH A 51,NIZAMUDDIN EAST, NEW DELHI 110013 [email protected] 15 A059 D1 MR ATUL NATH A-51, NIZAMUDDIN EAST, NEW DELHI 110013 [email protected] 16 A060 MR. -

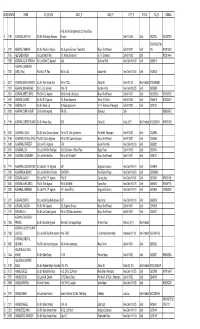

Main Voter List 08.01.2018.Pdf

Sl.NO ADM.NO NAME SO_DO_WO ADD1_R ADD2_R CITY_R STATE TEL_R MOBILE 61-B, Abul Fazal Apartments 22, Vasundhara 1 1150 ACHARJEE,AMITAVA S/o Shri Sudhamay Acharjee Enclave Delhi-110 096 Delhi 22620723 9312282751 22752142,22794 2 0181 ADHYARU,YASHANK S/o Shri Pravin K. Adhyaru 295, Supreme Enclave, Tower No.3, Mayur Vihar Phase-I Delhi-110 091 Delhi 745 9810813583 3 0155 AELTEMESH REIN S/o Late Shri M. Rein 107, Natraj Apartments 67, I.P. Extension Delhi-110 092 Delhi 9810214464 4 1298 AGARWAL,ALOK KRISHNA S/o Late Shri K.C. Agarwal A-56, Gulmohar Park New Delhi-110 049 Delhi 26851313 AGARWAL,DARSHANA 5 1337 (MRS.) (Faizi) W/o Shri O.P. Faizi Flat No. 258, Kailash Hills New Delhi-110 065 Delhi 51621300 6 0317 AGARWAL,MAM CHANDRA S/o Shri Ram Sharan Das Flat No.1133, Sector-29, Noida-201 301 Uttar Pradesh 0120-2453952 7 1427 AGARWAL,MOHAN BABU S/o Dr. C.B. Agarwal H.No. 78, Sukhdev Vihar New Delhi-110 025 Delhi 26919586 8 1021 AGARWAL,NEETA (MRS.) W/o Shri K.C. Agarwal B-608, Anand Lok Society Mayur Vihar Phase-I Delhi-110 091 Delhi 9312059240 9810139122 9 0687 AGARWAL,RAJEEV S/o Shri R.C. Agarwal 244, Bharat Apartment Sector-13, Rohini Delhi-110 085 Delhi 27554674 9810028877 11 1400 AGARWAL,S.K. S/o Shri Kishan Lal 78, Kirpal Apartments 44, I.P. Extension, Patparganj Delhi-110 092 Delhi 22721132 12 0933 AGARWAL,SUNIL KUMAR S/o Murlidhar Agarwal WB-106, Shakarpur, Delhi 9868036752 13 1199 AGARWAL,SURESH KUMAR S/o Shri Narain Dass B-28, Sector-53 Noida, (UP) Uttar Pradesh0120-2583477 9818791243 15 0242 AGGARWAL,ARUN S/o Shri Uma Shankar Agarwal Flat No.26, Trilok Apartments Plot No.85, Patparganj Delhi-110 092 Delhi 22433988 16 0194 AGGARWAL,MRIDUL (MRS.) W/o Shri Rajesh Aggarwal Flat No.214, Supreme Enclave Mayur Vihar Phase-I, Delhi-110 091 Delhi 22795565 17 0484 AGGARWAL,PRADEEP S/o Late R.P. -

41 S-II+Jangpura.Pdf

Election Commission of India Electoral Rolls for NCT of Delhi Back AC NAME LOCALITY LOCALITY DETAILS 41-JANGPURA 1-SARAI KALE KHAN 1 TO 447/2 2- A-BLOCK SARAI KALE KHAN 7 TO T86D 3-B - BLOCK SARAI KALE KHAN 34 TO T-86 4-T - BLOCK SARAI KALE KHAN 1 TO T-145 5-E - BLOCK ( BHOOT BANGLA ) SARAI KALE KHAN 76 TO 116 <> 1-HAZRAT NIZAMUDDIN NIZAMUDDIN (WEST) 3 TO T-B-36 2-DILDAR NAGAR BASTI HAZRAT NIZAMUDDIN 10/11 TO US 5/127 <> 1-NIZAM NAGAR HAZRAT NIZAMUDDIN NIZAMUDDIN (WEST) 1 TO VSA/5/86 2-KATRA NIZAMUDDIN (WEST) 23-T TO K- 556/104A 3-BASTI HZT NIZAMUDDIN 2 TO T-283 4- MUSHANWALI GALI, IMAMBRA NIZAMUDDIN WEST 18 TO A/47 5- IMAMBARA NIZAMUDDIN WEST 7-T TO 385-T <> 1-DILDAR ROAD NIZAMUDDIN WEST 2 TO T-561 2- KHUSRO NAGAR HAZRAT NIZAMUDDIN NIZAMUDDIN (WEST) 1 TO T-565 4- NALA PUSHTA, AMIR KHUSHRO NAGAR BASTI 3 TO T-423 <> 1-ITI ARAB KI SARAI, NIZAMUDEEN EAST, OPP POLICE STATION MATHURA ROAD 1 TO SHOP NO 1 <> 1-BUNGLOW NO 1- 35 NIZAMUDDIN EAST 1 TO 35 2-D- BLOCK 1-36 NIZAMUDDIN (EAST) 1 TO D-23 3- DAV SCHOOL POST OFFICE BLD NIZAMUDDIN EAST D A V TO PO BLDG 4-YMCA STAFF QTR NIZAMUDIN EAST 1 TO 4 <> 1-B-BLOCK MARKET NIZAMUDIN EAST 1 TO B-40 SF 2-B- BLOCK NIZAMUDIN EAST 1 TO B-28 3-C- BLOCK NIZAMUDDIN EAST 1 TO SNO-20 4- JAIPUR ESTATE NIZAMUDIN EAST 1 TO C-54 <> 1-MATHURA ROAD, JANGPURA B, BEHIND PRATAP MARKET NIZAMUDDIN EAST 5 TO R-24 2- MATHURA ROAD, JANGPURA B, B- BLOCK NIZAMUDDIN EAST 2 TO D-15 3- MATHURA ROAD, JANGPURA B, C- BLOCK NIZAMUDDIN EAST 7 TO C-63 4- MATHRA ROAD, JUNGPURA B, D- BLOCK NIZAMUDDIN EA ST 1 TO D-28 5- JUNGPURA B, PRATAP -

Conservation & Heritage Management

Chapter – 7 : Conservation & Heritage Management IL&FS ECOSMART Chapter – 7 Conservation & Heritage Management CHAPTER - 7 CONSERVATION & HERITAGE MANAGEMENT 7.1 INTRODUCTION Heritage Resource Conservation and Management imperatives for Delhi The distinctive historical pattern of development of Delhi, with sixteen identified capital cities1 located in different parts of the triangular area between the Aravalli ridge and the Yamuna river, has resulted in the distribution of a large number of highly significant heritage resources, mainly dating from the 13th century onwards, as an integral component within the contemporary city environment. (Map-1) In addition, as many of these heritage resources (Ashokan rock edict, two World Heritage Sites, most ASI protected monuments) are closely associated with the ridge, existing water systems, forests and open space networks, they exemplify the traditional link between natural and cultural resources which needs to be enhanced and strengthened in order to improve Delhi’s environment. (Map -2) 7.1.1 Heritage Typologies – Location and Significance These heritage resources continue to be of great significance and relevance to any sustainable development planning vision for Delhi, encompassing a vast range of heritage typologies2, including: 1. Archaeological sites, 2. Fortifications, citadels, different types of palace buildings and administrative complexes, 3. Religious structures and complexes, including Dargah complexes 4. Memorials, funerary structures, tombs 5. Historic gardens, 6. Traditional networks associated with systems of water harvesting and management 1 Indraprastha ( c. 1st millennium BCE), Dilli, Surajpal’s Surajkund, Anangpal’s Lal Kot, Prithviraj Chauhan’s Qila Rai Pithora, Kaiquabad’s Khilokhri, Alauddin Khilji’s Siri, Ghiyasuddin Tughlaq’s Tughlaqabad, Muhammad Bin Tughlaq’s Jahanpanah, Firoz Shah Tughlaq’s Firozabad, Khizr Khan’s Khizrabad, Mubarak Shah’s Mubarakabad, Humayun’s Dinpanah, Sher Shah Suri’s Dilli Sher Shahi, Shah Jehan’s Shahjehanabad, and Lutyen’s New Delhi. -

Contact Numbers +91-44-45605941 / +91-44-45605904 +91-11

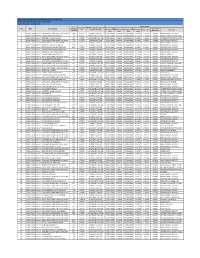

LIST OF UNCLAIMED DEPOSITS / INOPERATIVE ACCOUNTS (As of 31st-March-2019) Reserve Bank of India on February 7, 2012 has issued a circular on "Unclaimed Deposits/Inoperative Accounts in Banks-Display list of Inoperative Accounts". The list of Unclaimed Deposits/inoperative accounts which are inactive /inoperative for ten years or more have been displayed below. Branch Name Contact Person Contact Numbers Chennai Branch Ms Radha T / Mr S Balasubramanian +91-44-45605941 / +91-44-45605904 New Delhi Branch Mr P R Vishwanathan / Ms Amita Dhingra +91-11-43641239 / +91-11-43641275 Mumbai Branch Mr Mangesh Katagi / Mr Arun Khera +91-22-66693053 / +91-22-66693026 Name of the authorized signatory/ies in case S.No Name Address of non-individual a/c 1 A.K.KHANNA SHIMIZU CONST. LTD. PO BOX NO 776 , BAGHDAD , IRAQ 2 A.K.KHANNA SHIMIZU CONST. LTD. PO BOX NO 776 , BAGHDAD , IRAQ 3 A.K.VERMA (U.K.) 15, CEFN-COED ROAD, CYNCOED, CARDIFF,U.K AEVT VAN NESLAAN 70 , 2341 , HX OEGSTGEEST, THE 4 A.T.NATRAJAN (NETHERLANDS) NETHERLANDS 5 A.VIJAY KUMAR NO.4, SAN MARTIN MARG, CHANAKYAURI, NEW DELHI-110021 C/O ROYAL EMBASSY OF SAUDI ARABIA D-12, NDSE-II, NEW 6 ABDULLAH A. AL-SHOMRANI DELHI 110 049 10 OLD POST OFFICE STREET, ROOM NO -30 , CALCUTTA 7 ABHIJIT KUMAR MITTER 700001 C/O NIGERIA HIGH COMMISSION EP-4,CHANDRAGUPTA MARG, 8 ABRAHAM TORITSEJU POKO CHANAKYAPURI, NEW DELHI-110021 9 ACHALA SHARMA C-283 DDA FLATS, SAKET,NEW DELHI110017 10 ACHMAND D.JAMIRININ INDONESIA EMBASSY, CHANAKYA PURI, NEW DELHI 110021 11 ACME DECALS PVT LTD 1/1A,PADDAPUKUR LANE,CALCUTTA 700020 -

1 01/01/2018 Part of : OKHLA INDUSTRIAL AREA PH I BLOCK

Name of Distribution Licensee: BRPL Rajdhani Power Limited Period of Outage: Nov,Dec 2017 and Jan 2018 Name of Division: ALAKNANDA No. of Outage Detail Capacity of Wether Planned Outage or Sr. No. Date Area Effected consumer From To Unserved DT Unplanned Outage Duraction Remarks affected Date Time Date Time (MU) due to outage 1 01/01/2018 Part of : OKHLA INDUSTRIAL AREA PH I BLOCK 108 OTHER PLANNED OUTAGE 01/01/2018 11:00:00 01/01/2018 14:10:06 3:10:06 0.0264 MAINTENANCE ACTIVITY 2 02/01/2018 Part of : GOVIND PURI,GOVINDPURI, 12 OTHER UNPLANNED OUTAGE 02/01/2018 19:54:20 02/01/2018 21:17:52 1:23:32 0.0028 PROTECTION MALFUNCTION, 3 02/01/2018 Part of : GREATER KAILASH II BLOCK 28 OTHER UNPLANNED OUTAGE 02/01/2018 17:38:55 02/01/2018 18:23:21 0:44:26 0.0012 INTERRUPTION DUE TO FAULT 4 02/01/2018 Part of : OKHLA INDUSTRIAL AREA PH I BLOCK 773 OTHER PLANNED OUTAGE 02/01/2018 12:01:00 02/01/2018 16:34:51 4:33:51 0.0068 MAINTENANCE ACTIVITY 5 02/01/2018 Part of : RAJIV GANDHI COLONY,GOVIND 987 OTHER PLANNED OUTAGE 02/01/2018 11:50:00 02/01/2018 15:22:52 3:32:52 0.0118 MAINTENANCE ACTIVITY 6 03/01/2018 Part of : INDIRA KALYAN VIHAR,OKHLA 2112 OTHER PLANNED OUTAGE 03/01/2018 14:00:00 03/01/2018 16:58:35 2:58:35 0.0012 MAINTENANCE ACTIVITY 7 03/01/2018 Part of : GOVINDPURI,KALKAJI EXTENSION, 445 OTHER PLANNED OUTAGE 03/01/2018 11:01:00 03/01/2018 14:22:21 3:21:21 0.0012 MAINTENANCE ACTIVITY 8 03/01/2018 Part of : GOVINDPURI,KALKAJI EXTENSION, 1 OTHER PLANNED OUTAGE 03/01/2018 11:00:00 03/01/2018 14:15:43 3:15:43 0.0081 MAINTENANCE ACTIVITY 9 03/01/2018 -

Ministry of Urban Development Public

78 FUNCTIONING OF LAND AND DEVELOPMENT OFFICE [Action Taken by the Government on the Observations/Recommendations of the Committee contained in their Fifty-ninth Report (15th Lok Sabha)] MINISTRY OF URBAN DEVELOPMENT PUBLIC ACCOUNTS COMMITTEE 2012-2013 SEVENTY-EIGHTH REPORT FIFTEENTH LOK SABHA LOK SABHA SECRETARIAT NEW DELHI SEVENTY-EIGHTH REPORT PUBLIC ACCOUNTS COMMITTEE (2012-13) (FIFTEENTH LOK SABHA) FUNCTIONING OF LAND AND DEVELOPMENT OFFICE [Action Taken by the Government on the Observations/Recommendations of the Committee contained in their Fifty-ninth Report (15th Lok Sabha)] MINISTRY OF URBAN DEVELOPMENT Presented to Lok Sabha on 21 March, 2013 Laid in Rajya Sabha on 21 March, 2013 LOK SABHA SECRETARIAT NEW DELHI March, 2013 / Phalguna, 1934 (Saka) PAC No. 2005 Price : ` 155.00 © 2013 BY LOK SABHA SECRETARIAT Published under Rule 382 of the Rules of Procedure and Conduct of Business in Lok Sabha (Fourteenth Edition) and Printed by the General Manager, Government of India Press, Minto Road, New Delhi-110 002. CONTENTS PAGE COMPOSITION OF THE PUBLIC A CCOUNTS COMMITTEE (2012-13) ....................... (iii) INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................ (v) CHAPTER I Report ................................................................................. 1 CHAPTER II Observations/Recommendations which have been accepted by the Government . 11 CHAPTER III Observations/Recommendations which the Committee do not desire to pursue in view of the replies received from the Government. 103 CHAPTER IV Observations/Recommendations in respect of which replies of the Government have not been accepted by the Committee and which require reiteration . 104 CHAPTER V Observations/Recommendations in respect of which the Government have furnished interim replies . 138 APPENDICES I. Minutes of the Twenty-seventh sitting of the Public Accounts Committee (2012-13) held on 19th March, 2013 .