Corso Di Laurea Magistrale (Ordinamento Ex DM 270/2004)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MAY 2020 NEW TITLES FICTION WOLF HALL BRING up the BODIES Beautiful Hilary Mantel New Hilary Mantel

MAY 2020 NEW TITLES FICTION WOLF HALL BRING UP THE BODIES Beautiful Hilary Mantel New Hilary Mantel Winner of the Man Booker Prize Jackets! Winner of the Man Booker Prize 2012 Shortlisted for the Orange Prize Winner of the 2012 Costa Book of the Year Shortlisted for the Costa Novel Award Shortlisted for the 2013 Women’s Prize for Fiction `Dizzyingly, dazzlingly good' Daily Mail ‘Simply exceptional…I envy anyone who hasn’t yet read it’ Daily Mail ‘Our most brilliant English writer’ Guardian ‘A gripping story of tumbling fury and terror’ Independent England, the 1520s. Henry VIII is on the throne, but has no on Sunday heir. Cardinal Wolsey is his chief advisor, charged with securing the divorce the pope refuses to grant. Into this With this historic win for Bring Up the Bodies, Hilary Mantel atmosphere of distrust and need comes Thomas Cromwell, becomes the first British author and the first woman to be first as Wolsey's clerk, and later his successor. awarded two Man Booker Prizes. Cromwell is a wholly original man: the son of a brutal By 1535 Thomas Cromwell is Chief Minister to Henry VIII, his blacksmith, a political genius, a briber, a charmer, a bully, a fortunes having risen with those of Anne Boleyn, the king’s man with a delicate and deadly expertise in manipulating new wife. But Anne has failed to give the king an heir, and people and events. Ruthless in pursuit of his own interests, he Cromwell watches as Henry falls for plain Jane Seymour. is as ambitious in his wider politics as he is for himself. -

Mary Stuart and Elizabeth 1 Notes for a CE Source Question Introduction

Mary Stuart and Elizabeth 1 Notes for a CE Source Question Introduction Mary Queen of Scots (1542-1587) Mary was the daughter of James V of Scotland and Mary of Guise. She became Queen of Scotland when she was six days old after her father died at the Battle of Solway Moss. A marriage was arranged between Mary and Edward, only son of Henry VIII but was broken when the Scots decided they preferred an alliance with France. Mary spent a happy childhood in France and in 1558 married Francis, heir to the French throne. They became king and queen of France in 1559. Francis died in 1560 of an ear infection and Mary returned to Scotland a widow in 1561. During Mary's absence, Scotland had become a Protestant country. The Protestants did not want Mary, a Catholic and their official queen, to have any influence. In 1565 Mary married her cousin and heir to the English throne, Henry Stuart, Lord Darnley. The marriage was not a happy one. Darnley was jealous of Mary's close friendship with her secretary, David Rizzio and in March 1566 had him murdered in front of Mary who was six months pregnant with the future James VI and I. Darnley made many enemies among the Scottish nobles and in 1567 his house was blown up. Darnley's body was found outside in the garden, he had been strangled. Three months later Mary married the chief suspect in Darnley’s murder, the Earl of Bothwell. The people of Scotland were outraged and turned against her. -

An Ideal Husband

PRODUCTION CO-SPONSOR: SUPPORT FOR THE 2018 SEASON OF THE AVON THEATRE IS GENEROUSLY PROVIDED BY THE BIRMINGHAM FAMILY PRODUCTION SUPPORT IS GENEROUSLY PROVIDED BY NONA MACDONALD HEASLIP AND BY DR. ROBERT & ROBERTA SOKOL 2 CLASSICLASSIC FILMS OscarWildeCinema.com TM CINEPLEX EVENTS OPERA | DANCE | STAGE | GALLERY | CLASSIC FILMS For more information, visit Cineplex.com/Events @CineplexEvents EVENTS ™/® Cineplex Entertainment LP or used under license. CE_0226_EVCN_CPX_Events_Print_AD_5.375x8.375_v4.indd 1 2018-03-08 7:41 AM THE WILL TO BE FREE We all want to be free. But finding true freedom within our communities, within our families and within ourselves is no easy task. Nor is it easy to reconcile our own freedom with the political, religious and cultural freedoms of others. Happily, the conflict created by our search for freedom makes for great theatre... Shakespeare’s The Tempest, in which I’m delighted to direct Martha Henry, is a play about the yearning to be released from CLASSICCLASSI FILMS imprisonment, as revenge and forgiveness vie OscarWildeCinema.com TM for the upper hand in Prospero’s heart. Erin Shields’s exciting new interpretation of Milton’s Paradise Lost takes an ultra- contemporary look at humanity’s age-old desire for free will – and the consequences of acting on it. I’m very proud that we have the internationally renowned Robert Lepage with us directing Shakespeare’s Coriolanus, a play about early Roman democracy. It is as important to understanding the current state of our democratic institutions as is Shakespeare’s play about the end of the Roman Republic, Julius Caesar. Recent events have underlined the need for the iconic story To Kill a Mockingbird to be told, as a powerful reminder that there can be no freedom without justice. -

Introduction

NOTES INTRODUCTION 1. Nathanael West, The Day of the Locust (New York: Bantam, 1959), 131. 2. West, Locust, 130. 3. For recent scholarship on fandom, see Henry Jenkins, Textual Poachers: Television Fans and Participatory Culture (New York: Routledge, 1992); John Fiske, Understanding Popular Culture (New York: Routledge, 1995); Jackie Stacey, Star Gazing (New York: Routledge, 1994); Janice Radway, Reading the Romance (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina, 1991); Joshua Gam- son, Claims to Fame: Celebrity in Contemporary America (Berkeley: Univer- sity of California Press, 1994); Georganne Scheiner, “The Deanna Durbin Devotees,” in Generations of Youth, ed. Joe Austin and Michael Nevin Willard (New York: New York University Press, 1998); Lisa Lewis, ed. The Adoring Audience: Fan Culture and Popular Media (New York: Routledge, 1993); Cheryl Harris and Alison Alexander, eds., Theorizing Fandom: Fans, Subculture, Identity (Creekskill, N.J.: Hampton Press, 1998). 4. According to historian Daniel Boorstin, we demand the mass media’s simulated realities because they fulfill our insatiable desire for glamour and excitement. To cultural commentator Richard Schickel, they create an “illusion of intimacy,” a sense of security and connection in a society of strangers. Ian Mitroff and Warren Bennis have gone as far as to claim that Americans are living in a self-induced state of unreality. “We are now so close to creating electronic images of any existing or imaginary person, place, or thing . so that a viewer cannot tell whether ...theimagesare real or not,” they wrote in 1989. At the root of this passion for images, they claim, is a desire for stability and control: “If men cannot control the realities with which they are faced, then they will invent unrealities over which they can maintain control.” In other words, according to these authors, we seek and create aural and visual illusions—television, movies, recorded music, computers—because they compensate for the inadequacies of contemporary society. -

A Dangerous Method

A David Cronenberg Film A DANGEROUS METHOD Starring Keira Knightley Viggo Mortensen Michael Fassbender Sarah Gadon and Vincent Cassel Directed by David Cronenberg Screenplay by Christopher Hampton Based on the stage play “The Talking Cure” by Christopher Hampton Based on the book “A Most Dangerous Method” by John Kerr Official Selection 2011 Venice Film Festival 2011 Toronto International Film Festival, Gala Presentation 2011 New York Film Festival, Gala Presentation www.adangerousmethodfilm.com 99min | Rated R | Release Date (NY & LA): 11/23/11 East Coast Publicity West Coast Publicity Distributor Donna Daniels PR Block Korenbrot Sony Pictures Classics Donna Daniels Ziggy Kozlowski Carmelo Pirrone 77 Park Ave, #12A Jennifer Malone Lindsay Macik New York, NY 10016 Rebecca Fisher 550 Madison Ave 347-254-7054, ext 101 110 S. Fairfax Ave, #310 New York, NY 10022 Los Angeles, CA 90036 212-833-8833 tel 323-634-7001 tel 212-833-8844 fax 323-634-7030 fax A DANGEROUS METHOD Directed by David Cronenberg Produced by Jeremy Thomas Co-Produced by Marco Mehlitz Martin Katz Screenplay by Christopher Hampton Based on the stage play “The Talking Cure” by Christopher Hampton Based on the book “A Most Dangerous Method” by John Kerr Executive Producers Thomas Sterchi Matthias Zimmermann Karl Spoerri Stephan Mallmann Peter Watson Associate Producer Richard Mansell Tiana Alexandra-Silliphant Director of Photography Peter Suschitzky, ASC Edited by Ronald Sanders, CCE, ACE Production Designer James McAteer Costume Designer Denise Cronenberg Music Composed and Adapted by Howard Shore Supervising Sound Editors Wayne Griffin Michael O’Farrell Casting by Deirdre Bowen 2 CAST Sabina Spielrein Keira Knightley Sigmund Freud Viggo Mortensen Carl Jung Michael Fassbender Otto Gross Vincent Cassel Emma Jung Sarah Gadon Professor Eugen Bleuler André M. -

Shakespeare, Middleton, Marlowe

UNTIMELY DEATHS IN RENAISSANCE DRAMA UNTIMELY DEATHS IN RENAISSANCE DRAMA: SHAKESPEARE, MIDDLETON, MARLOWE By ANDREW GRIFFIN, M.A. A Thesis Submitted to the School of Graduate Studies in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy McMaster University ©Copyright by Andrew Griffin, July 2008 DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY (2008) McMaster University (English) Hamilton, Ontario TITLE: Untimely Deaths in Renaissance Drama: Shakespeare, Middleton, Marlowe AUTHOR: Andrew Griffin, M.A. (McMaster University), B.A. (Queen's University) SUPERVISOR: Professor Helen Ostovich NUMBER OF PAGES: vi+ 242 ii Abstract In this dissertation, I read several early modem plays - Shakespeare's Richard II, Middleton's A Chaste Maid in Cheapside, and Marlowe's Dido, Queene ofCarthage alongside a variety of early modem historiographical works. I pair drama and historiography in order to negotiate the question of early modem untimely deaths. Rather than determining once and for all what it meant to die an untimely death in early modem England, I argue here that one answer to this question requires an understanding of the imagined relationship between individuals and the broader unfolding of history by which they were imagined to be shaped, which they were imagined to shape, or from which they imagined to be alienated. I assume here that drama-particularly historically-minded drama - is an ideal object to consider when approaching such vexed questions, and I also assume that the problematic of untimely deaths provides a framework in which to ask about the historico-culturally specific relationships that were imagined to obtain between subjects and history. While it is critically commonplace to assert that early modem drama often stages the so-called "modem" subject, I argue here that early modem visions of the subject are often closely linked to visions of that subject's place in the world, particularly in the world that is recorded by historiographers as a world within and of history. -

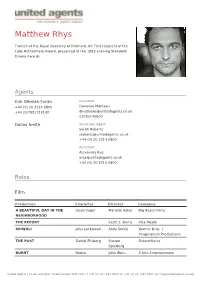

Matthew Rhys

Matthew Rhys Trained at the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art First recipient of the Lady Rothermere Award, presented at the 1993 Evening Standard Drama Awards Agents Kirk Whelan-Foran Assistant +44 (0) 20 3214 0800 Donovan Mathews +44 (0)7920713142 [email protected] 02032140800 Dallas Smith Associate Agent Sarah Roberts [email protected] +44 (0) 20 3214 0800 Assistant Alexandra Rae [email protected] +44 (0) 20 3214 0800 Roles Film Production Character Director Company A BEAUTIFUL DAY IN THE Lloyd Vogel Marielle Heller Big Beach Films NEIGHBORHOOD THE REPORT Scott Z. Burns Vice Media MOWGLI John Lockwood Andy Serkis Warner Bros. | Imaginarium Productions THE POST Daniel Ellsberg Steven DreamWorks Spielberg BURNT Reece John Wells 3 Arts Entertainment United Agents | 12-26 Lexington Street London W1F OLE | T +44 (0) 20 3214 0800 | F +44 (0) 20 3214 0801 | E [email protected] Production Character Director Company THE SCAPEGOAT John Charles Island Pictures Sturridge LUSTER Joseph Miller ADAM MASON Azurelight Pictures PATAGONIA Mateo Marc Evans Rainy Day Films ABDUCTION CLUB Strang Steven Schwartz Pathe DEATHWATCH Doc M.J. Bassett Pathe FAKERS Nick Blake Richard Janes Faking It Productions COME WHAT MAY Percy Christian Carion Nord-Ouest Productions GUILTY PLEASURES Count David Leland Boccaccio Productions Dzerzhinsky HEART Sean Charles Granada McDougal HOUSE OF AMERICA Boyo Marc Evans September Films LOVE AND OTHER DISASTERS Peter Simon Alek Keshishian Skyline Ltd PAVAROTTI IN DAD'S ROOM Nob Sara Sugarman Dragon -

American Auteur Cinema: the Last – Or First – Great Picture Show 37 Thomas Elsaesser

For many lovers of film, American cinema of the late 1960s and early 1970s – dubbed the New Hollywood – has remained a Golden Age. AND KING HORWATH PICTURE SHOW ELSAESSER, AMERICAN GREAT THE LAST As the old studio system gave way to a new gen- FILMFILM FFILMILM eration of American auteurs, directors such as Monte Hellman, Peter Bogdanovich, Bob Rafel- CULTURE CULTURE son, Martin Scorsese, but also Robert Altman, IN TRANSITION IN TRANSITION James Toback, Terrence Malick and Barbara Loden helped create an independent cinema that gave America a different voice in the world and a dif- ferent vision to itself. The protests against the Vietnam War, the Civil Rights movement and feminism saw the emergence of an entirely dif- ferent political culture, reflected in movies that may not always have been successful with the mass public, but were soon recognized as audacious, creative and off-beat by the critics. Many of the films TheThe have subsequently become classics. The Last Great Picture Show brings together essays by scholars and writers who chart the changing evaluations of this American cinema of the 1970s, some- LaLastst Great Great times referred to as the decade of the lost generation, but now more and more also recognised as the first of several ‘New Hollywoods’, without which the cin- American ema of Francis Coppola, Steven Spiel- American berg, Robert Zemeckis, Tim Burton or Quentin Tarantino could not have come into being. PPictureicture NEWNEW HOLLYWOODHOLLYWOOD ISBN 90-5356-631-7 CINEMACINEMA ININ ShowShow EDITEDEDITED BY BY THETHE -

Early Elizabethan England Revision Booklet NAME:______

Early Elizabethan England Revision Booklet NAME:____________ Contents Tick when complete Topic 1 • How did Elizabeth’s Early Life affect her later decisions? p 2-3 What were the • What were the threats to Elizabeth’s succession? P 3-5 early threats to • How did Elizabeth govern? P6 Elizabeth’s reign? • What was the Religious Settlement? 7-10 • How serious was the Puritan Challenge? P 11-12 • Why was Mary Queen of Scots a Threat 1858-1868? p 12-13 • Knowledge and Exam Question Checklist p 14 Topic 2 • What were the causes of the Revolt of the Northern Earls p15-16 What were the Catholic • Which Plot was the greatest threat to Elizabeth? P 17-19 Plots that threatened • Why was Mary Queen of Scots executed in 1587? P20-21 Elizabeth? Why did England go to War with • Why did England go to war with Spain in 1585? p22-24 Spain in 1585? Why was • Why was the Spanish Armada defeated in 1588? p24-26 the Armada defeated in • Knowledge and Exam Question Checklist p 27 1588? Topic 3 • Why did poverty increase in Elizabethan England? p28-29 Elizabethan Society in • Why were Elizabethans so scared of Vagabonds? p30-33 the Age of exploration • Why did Drake and Raleigh go on voyages around the world and what did they discover? p33-36 • Why did the Virginia colonies fail? p37-40 • Was there a Golden Age for all Elizabethans? P41-43 • Knowledge and Exam Question Checklist p 44 Quizzes • Topic 1 p 45-46 • Topic 2 p 47-48 • Topic 3 p 49-50 Learning Ladder • 16 mark p 51 • 12 mark p 52 • 4 mark p 53 1 Topic 1 pages 2-14 How did Elizabeth’s Early Life affect her later decisions? 1. -

RFC's Library's Book Guide

RFC’s Library’s Book Guide 2017 Since the beginning of our journey at the Royal Film Commission – Jordan (RFC), we have been keen to provide everything that promotes cinema culture in Jordan; hence, the Film Library was established at the RFC’s Film House in Jabal Amman. The Film Library offers access to a wide and valuable variety of Jordanian, Arab and International movies: the “must see” movies for any cinephile. There are some 2000 titles available from 59 countries. In addition, the Film Library has 2500 books related to various aspects of the audiovisual field. These books tackle artistic, technical, theoretical and historical aspects of cinema and filmmaking. The collec- tion of books is bilingual (English and Arabic). Visitors can watch movies using the private viewing stations available and read books or consult periodi- cals in a calm and relaxed atmosphere. Library members are, in addition, allowed to borrow films and/or books. Membership fees: 20 JOD per year; 10 JOD for students. Working hours: The Film Library is open on weekdays from 9:00 AM until 8:00 PM. From 3:00 PM until 8:00 PM on Saturdays. It is closed on Fridays. RFC’s Library’s Book Guide 2 About People In Cinema 1 A Double Life: George Cukor Patrick McGilligan 2 A Hitchcock Reader Marshall Dentelbaum & Leland Poague 3 A life Elia Kazan 4 A Man With a Camera Nestor Almenros 5 Abbas Kiarostami Saeed-Vafa & Rosenbaum 6 About John Ford Lindsay Anderson 7 Adventures with D.W. Griffith Karl Brown 8 Alexander Dovzhenko Marco Carynnk 9 All About Almodovar Epps And Kakoudeki -

The Examination of Mary Queen of Scots

Some matters appertaining to the accusation, trial, and execution of Mary Queen of Scots Being letters and records of that perilous time with Clarification and Notes by ye humble Editrix Maggie Pierce Secara Selected, Edited, Mapped, and Adapted for Modern Readers from History of the Life of Mary Queen of Scots, 1681 The Contents The Examination of Mary Queen of Scots .......................................................................................... 4 Wednesday, 12 October ............................................................................................................................................. 4 Thursday, 13 October ................................................................................................................................................. 4 Friday, 14 October ...................................................................................................................................................... 4 Queen Elizabeth’s Letter directed to Sir Amyas Paulet, Knight, keeper of the Queen of Scots, at the castle of Fotheringay ........................................................................................................................ 14 The Scottish Queen’s Letter to Anthony Babington ............................................................................ 15 Anthony Babington a Letter written by him to the Scottish Queen ...................................................... 16 The answer of the Scottish Queen to a Letter written by Anthony Babington, the Traitor, as followeth -

Findley, Timothy (1930-2002) by Linda Rapp

Findley, Timothy (1930-2002) by Linda Rapp Encyclopedia Copyright © 2015, glbtq, Inc. Entry Copyright © 2005, glbtq, inc. Reprinted from http://www.glbtq.com Award-winning Canadian writer Timothy Findley produced works in a number of genres, including plays, novels, and short stories. While his works are impossible to pigeon-hole, they often examine the nature of power in society and the struggle of people to understand and achieve what is right. Timothy Irving Frederick Findley--"Tiff" to his friends--was born into a prosperous Toronto family on October 30, 1930 and grew up in the fashionable Rosedale section of the city. His father was the first person outside of the founding families to head the Massey-Ferguson company. His mother's family had a piano factory. Although Findley grew up in a privileged environment, his childhood was far from happy. Under the influence of alcohol his father frequently terrorized Findley's mother and older brother. Findley himself generally escaped his wrath, but, in the words of journalist Alec Scott, "vicarious scar tissue developed nonetheless" in the sensitive young boy. Findley suffered from poor health as a child. He nearly died of pneumonia in his second year, and shortly thereafter he was confined to an oxygen tent due to complications of an ear infection. Findley was a bookish youth who loved creating his own worlds of make-believe. He was not, however, a particularly avid student. He dropped out of high school at the age of sixteen in order to study ballet. A fused disc put an end to Findley's hopes of a career in dance, and he turned to acting.