NOTES on JEREMIAH 20:7-13 Richard D. Weis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jeremiah Commentary

YOU CAN UNDERSTAND THE BIBLE JEREMIAH BOB UTLEY PROFESSOR OF HERMENEUTICS (BIBLE INTERPRETATION) STUDY GUIDE COMMENTARY SERIES OLD TESTAMENT, VOL. 13A BIBLE LESSONS INTERNATIONAL MARSHALL, TEXAS 2012 www.BibleLessonsIntl.com www.freebiblecommentary.org Copyright ©2001 by Bible Lessons International, Marshall, Texas (Revised 2006, 2012) All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any way or by any means without the written permission of the publisher. Bible Lessons International P. O. Box 1289 Marshall, TX 75671-1289 1-800-785-1005 ISBN 978-1-892691-45-3 The primary biblical text used in this commentary is: New American Standard Bible (Update, 1995) Copyright ©1960, 1962, 1963, 1968, 1971, 1972, 1973, 1975, 1977, 1995 by The Lockman Foundation P. O. Box 2279 La Habra, CA 90632-2279 The paragraph divisions and summary captions as well as selected phrases are from: 1. The New King James Version, Copyright ©1979, 1980, 1982 by Thomas Nelson, Inc. Used by permission. All rights reserved. 2. The New Revised Standard Version of the Bible, Copyright ©1989 by the Division of Christian Education of National Council of the Churches of Christ in the U. S. A. Used by permission. All rights reserved. 3. Today’s English Version is used by permission of the copyright owner, The American Bible Society, ©1966, 1971. Used by permission. All rights reserved. 4. The New Jerusalem Bible, copyright ©1990 by Darton, Longman & Todd, Ltd. and Doubleday, a division of Bantam Doubleday Dell Publishing Group, Inc. Used by permission. All rights reserved. www.freebiblecommentary.org The New American Standard Bible Update — 1995 Easier to read: } Passages with Old English “thee’s” and “thou’s” etc. -

The Suffering of the Prophet Jeremiah

MINISTRY The Suffering of the Prophet Jeremiah Drs. H. Lalleman-de Winkel graduated from Utrecht State University, taking Old Testament as her main subject. She wrote a thesis on Medical Metaphors in the Book of Jeremiah, and ·continues research on that book. We live in a remarkable time. In our western world with its Biographical Sections. material prosperity we can get almost everything we want. Even In those parts of the book which tell of Jeremiah' s life, what we if not all are rich, generally speaking we have more than we really read in the story of his call is developed: his message ofjudgment need. Yet even in our modern world money cannot buy freedom is not accepted with enthusiasm; indeed the story has been called from sorrow and suffering. So many books are written on this a 'passion narrative'. Let us consider some of these reports which theme nowadays, (for instance the book by Harold S. Kushner relate to Jeremiah's suffering. When bad things happen to good people•), along with books about: how to be healthy, successful in business, etc. Suffering Jeremiah 20: 1-2 describes how Jeremiah is captured by the chief does not agree with our success, and so it hardly figures in our officer in the temple, Pashhur; he is considered a disturber of the thinking. The book of Jeremiah offers one model of suffering. peace (cf. 29:26, apparently this happened more often). People Even if the suffering of Jeremiah has certain specific meanings take offence at his message of judgment, he is beaten and put in which do not apply to suffering in general, some analogies with a kind of straitjacket. -

The Imprisonment of Jeremiah in Its Historical Context

The Imprisonment of Jeremiah in Its Historical Context kevin l. tolley Kevin L. Tolley ([email protected]) is the coordinator of Seminaries and Institutes of Religion in Fullerton, California. he book of Jeremiah describes the turbulent times in Jerusalem prior to Tthe Babylonian conquest of the city. Warring political factions bickered within the city while a looming enemy rapidly approached. Amid this com- . (wikicommons). plex political arena, Jeremiah arose as a divine spokesman. His preaching became extremely polarizing. These political factions could be categorized along a spectrum of support and hatred toward the prophet. Jeremiah’s imprisonment (Jeremiah 38) illustrates some of the various attitudes toward God’s emissary. This scene also demonstrates the political climate and spiritual atmosphere of Jerusalem at the verge of its collapse into the Babylonian exile and also gives insights into the beginning narrative of the Book of Mormon. Jeremiah Lamenting the Destruction of Jerusalem Jeremiah Setting the Stage: Political Background for Jeremiah’s Imprisonment In the decades before the Babylonian exile in 587/586 BC, Jerusalem was the center of political and spiritual turmoil. True freedom and independence had Rembrandt Harmensz, Rembrandt not been enjoyed there for centuries.1 Subtle political factions maneuvered The narrative of the imprisonment of Jeremiah gives us helpful insights within the capital city and manipulated the king. Because these political into the world of the Book of Mormon and the world of Lehi and his sons. RE · VOL. 20 NO. 3 · 2019 · 97–11397 98 Religious Educator ·VOL.20NO.3·2019 The Imprisonment of Jeremiah in Its Historical Context 99 groups had a dramatic influence on the throne, they were instrumental in and closed all local shrines, centralizing the worship of Jehovah to the temple setting the political and spiritual stage of Jerusalem. -

For Reference Only

HisHisHis WorldWorldWorld FOR REFERENCE ONLY 20222022 LUTHERAN CALENDAR nd he said, The LORD is my rock, and my fortress, and my deliverer; A - II Samuel 22:2 FOR REFERENCE ONLY January 2022 SUNDAY MONDAY TUESDAY WEDNESDAY THURSDAY FRIDAY SATURDAY DECEMBER FEBRUARY S M T W T F S S M T W T F S 1 1 2 3 4 1 2 3 4 5 New Moon 2 NEW YEAR’S DAY 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 First Quarter 9 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 Full Moon 17 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 Last Quarter 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 27 28 HOLY NAME OF JESUS Numbers 6:22-27 The Aaronic blessing 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 2nd SUNDAY AFTER CHRISTMAS Jeremiah 31:7-14 EPIPHANY OF THE LORD Daniel 2:24-49 Joy as God’s scattered Job 42:10-17 Isaiah 6:1-5 John 1:[1-9] 10-18 Isaiah 60:1-6 Daniel 2:1-19 Daniel reveals the flock gathers Job’s family The Lord high and lofty God with us Nations come to the light The king searches for wisdom dream’s meaning 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 BAPTISM OF THE LORD Isaiah 43:1-7 Judges 4:1-16 Judges 5:12-21 Psalm 106:1-12 Jeremiah 3:1-5 Jeremiah 3:19-25 Jeremiah 4:1-4 PassingFOR through the waters Israel’s enemies drownREFERENCEThe song of Deborah God saves through water Unfaithful Israel IsraelONLY is a faithless spouse A call to repentance 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 MARTIN LUTHER KING JR. -

Jeremiah 20:7-9 You Can't Quit by Rev. Jeremiah Parks Intro

Parks 1 Jeremiah 20:7-9 You Can’t Quit By Rev. Jeremiah Parks Intro: There is a story told about a champion greyhound racinG doG that ran across the tracks of Europe at break neck speed. This champion developed a followinG because it had never lost a race. In and around the tracks of Europe and ultimately in the United States , one particular fan ran to the paper reGularly to see the speed that this greyhound racinG doG would run. This fan finally saw in the paper that the DoG’s owner was bringing this doG from Europe to the U.S. to race. The race was 4 states over therefore this fan saved his money, packed up his car and decided to drive 4 states over to witness in person this champion greyhound racinG doG. He got to the track that day, walked up to the betting booth put his money on the counter and told the betting booth operator “I will like to place my bet on that European racinG doG that is cominG to race today. That operator looked at him © 2018 Rev. Jeremiah Parks This sermon was delivered at Baylor University’s Truett Theological Seminary on November 28, 2018. Published with permission for "Baptists Preaching" column on www.BaptistStandard.com. Parks 2 and said I am sorry sir, but the doG isn’t racinG. Quite upset, the man told the operator sir you don’t understand. I been followinG this doG’s career for quite some time, I looked at this doGs career in the newspaper, I know that he is racinG today in fact I saved my money, packed up my car and have driven 4 states over. -

THRU the BIBLE EXPOSITION Jeremiah

THRU THE BIBLE EXPOSITION Jeremiah: Prophet Of Judgment Followed By Blessing Part XLI: The Great Value Of Jeremiah's Personal Struggle With His Persecutions (Jeremiah 20:7-18) I. Introduction A. Though Jeremiah rightly handled being persecuted by the chief officer of the temple, Pashhur, at the time the persecution occurred, later in private, the incident bothered him, creating a struggle of faith in Jeremiah. B. We view that struggle in Jeremiah 20:7-18 in light of its context in the rest of Scripture for edifying insight: II. The Great Value Of Jeremiah's Personal Struggle With His Persecutions, Jeremiah 20:7-18. A. Jeremiah initially privately complained to the Lord about the persecutions he had faced, Jeremiah 20:7-10: 1. After interacting with Pashhur, Jeremiah privately complained to the Lord that God had deceived him in letting him be ridiculed by Pashhur and the people for his message, Jer. 20:7a; Bible Know. Com., O. T., p. 1154. Jeremiah had known from the beginning that all his hearers would oppose him (Jer. 1:18-19a), but he was not aware that they would ridicule him, what was especially horrible for Jeremiah to face! 2. Jeremiah added that whenever he spoke, he cried out, proclaiming violence and destruction, but speaking this message of the Lord had only brought him insult and reproach all day long, Jeremiah 20:7b-8. 3. Discouraged by it all, Jeremiah considered not mentioning the Lord or speaking of His name again. However, trying to do that only created an intolerable tension as the Word of God within was like a fire shut up in Jeremiah's bones to where he would be weary of holding it in, so he would speak it, Jer. -

Jeremiad Lamentations

JEREMIAD LAMENTATIONS >, OJ oo QJ co .c .;;:u co .S! :0ro C') m m Assyrian soldiers with battering ram attacking Lachish (2 Kings 18:13-14) The career of the prophet Jeremiah prophet as well as the book that bears his spanned the most turbulent years in the his name, let's sketch briefly the main historical tory of Jerusalem and Judah. Called to be a events of Jeremiah's day. prophet in 626 B.C., his last activity of The time of Jeremiah's call coincided which we have knowledge occuned in the with the beginning of the demise of the late 580's. For almost forty years he carried hated Assyrian Empire. For over one hun the burdens of Judah's life. But he could dred years the Assyrians had ruled most of not tum the tide that eventually led to the the Near East, including Judah. They had destruction of the state, the holy city of governed with an iron hand and a heal1 of Jerusalem, the sacred Temple, and the cho stone. War scenes dominated Assyrian art sen dynasty of the Davidic family. towns being captured, exiles being led In order to understand the career of this away, prisoners being impaled on sharp BOOKS OF TIlE BIBLE 86 people's obedience to God and to God's qUESTIONS FOR transformation of the world. Read the DISCUSSION words about the future in Isaiah 65:17-18. 1. Scholars hold the opinion that our pres Read Isaiah 55:6-11 and answer the ques ent book is actually made up of the work of tions below. -

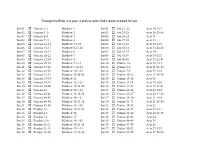

Through the Bible in a Year: a Plan to Learn God's Word Revealed for You Jan-01 Genesis 1,2 Matthew 1 Jul-01 Job 21, 22

Through the Bible in a year: a plan to learn God's word revealed for you Jan-01 o Genesis 1,2 Matthew 1 Jul-01 o Job 21, 22 Acts 10:1-23 Jan-02 o Genesis 3, 5 Matthew 2 Jul-02 o Job 23-25 Acts 10:24-48 Jan-03 o Genesis 6-8 Matthew 3 Jul-03 o Job 26-28 Acts 11 Jan-04 o Genesis 9-11 Matthew 4 Jul-04 o Job 29,30 Acts 12 Jan-05 o Genesis 12-14 Matthew 5:1-26 Jul-05 o Job 31,32 Acts 13:1-23 Jan-06 o Genesis 15-17 Matthew 5:27-48 Jul-06 o Job 33,34 Acts 13:24-52 Jan-07 o Genesis 18,19 Matthew 6 Jul-07 o Job 35-37 Acts 14 Jan-08 o Genesis 20-22 Matthew 7 Jul-08 o Job 38,39 Acts 15:1-21 Jan-09 o Genesis 23,24 Matthew 8 Jul-09 o Job 40-42 Acts 15:22-41 Jan-10 o Genesis 25,26 Matthew 9:1-17 Jul-10 o Psalms 1-3 Acts 16:1-15 Jan-11 o Genesis 27,28 Matthew 9:18-38 Jul-11 o Psalms 4-6 Acts 16:16-40 Jan-12 o Genesis 29,30 Matthew 10:1-23 Jul-12 o Psalms 7-9 Acts 17:1-15 Jan-13 o Genesis 31,32 Matthew 10:24-42 Jul-13 o Psalms 10-12 Acts 17:16-34 Jan-14 o Genesis 33-35 Matthew 11 Jul-14 o Psalms 13-16 Acts 18 Jan-15 o Genesis 36,37 Matthew 12:1-21 Jul-15 o Psalms 17,18 Acts 19:1-20 Jan-16 o Genesis 38-40 Matthew 12:22-50 Jul-16 o Psalms 19-21 Acts 19:21-41 Jan-17 o Genesis 41 Matthew 13:1-32 Jul-17 o Psalms 22-24 Acts 20:1-16 Jan-18 o Genesis 42,43 Matthew 13:33-58 Jul-18 o Psalms 25-27 Acts 20:17-38 Jan-19 o Genesis 44,45 Matthew 14:1-21 Jul-19 o Psalms 28-30 Acts 21:1-14 Jan-20 o Genesis 46-48 Matthew 14:22-36 Jul-20 o Psalms 31-33 Acts 21:15-40 Jan-21 o Genesis 49,50 Matthew 15:1-20 Jul-21 o Psalms 34,35 Acts 22 Jan-22 o Exodus 1-3 Matthew 15:21-39 -

Jeremiah “A Dying Nation”

Jeremiah “A Dying Nation” I. Introduction to Jeremiah the Book Jeremiah is the 24th book of the Old Testament and the second of the Major Prophets. .Jeremiah has 52 chapters, and by word count is the longest of the prophetic books. It chronologically follows the book of Isaiah. Isaiah watched the fall of Israel to Assyria and prophesied of a better day when Messiah would suffer for the sins of man, and ultimately reign supreme. Jeremiah watched as Judah fell to Babylon and prophesied of a remnant returning to Israel after seventy years of captivity. This captivity was both punitive and corrective. During the captivity, Israel would be cured of its idolatry and the way would be paved for the coming Messiah. Jeremiah’s prophesies follow approximately sixty to eighty years after Isaiah and during the reigns of Josiah, Jehoiakim and Zedediah. Jeremiah is best understood when seen in light of 2 Kings 22-25 and 2 Chronicles 34-36. At sixteen years of age, young King Josiah began to seek the Lord and by age twenty, he purged Judah and Jerusalem of altars, images and high places. At twenty-six he began a Temple restoration project to restore worship of YHWH and insight revival in the people. It was during this time Hilkiah found a copy of the law of God. When it was read to King Josiah, he repented of personal sin and called the nation to turn to the Lord. Thousands, in Israel devoted themselves to the Lord. This would be the final revival in Israel’s history. -

From Karen Meikle Defining Moments Sojourner

From Karen Meikle Defining Moments Sojourner It would seem that names are important to God! Today we generally name our children a name we simply like, or perhaps after a particularly beloved family member. However, in the Bible people are often named because of something distinct about their character, identity, or mission. Not only that, but God seems to find it important in certain instances to change the person's name to reflect an event that has happened and how that event will shape their future. Abram (exalted father) becomes Abraham because this new name reflects God's covenant with him, as it means “father of many nations.” Even people who would seem insignificant in the Biblical story have their names changed by God. In Jeremiah 20 we met Pashur, a priest who did not like the message of disaster that Jeremiah (meaning, “Yahweh will raise”) was bringing to the people. His response was to beat up Jeremiah and place him in the stocks. Upon his release, Jeremiah said to him: “The LORD's name for you is not Pashur, but Terror on Every Side” (Jeremiah 20:3). Not a name that rolls off the tongue, but perhaps appropriate for a couple of kids that I know! If names are important to God, then how does God refer to himself? There are two main ways that our translations refer to God: God and LORD. God is a translation of the word Elohim. And LORD is the way that the English translators chose to translate the word, Yahweh, originally YHWH in the Hebrew. -

Jerome's Reading of Jeremiah 20:7-18

Este artigo é parte integrante da revista.batistapioneira.edu.br ONLINE ISSN 2316-686X - IMPRESSO ISSN 2316-462X Vol. 6 n. 2 Dezembro | 2017 JEROME’S READING OF JEREMIAH 20:7-18 A leitura de Jerônimo de Jeremias 20:7-18 Me. Igor Pohl Baumann1 ABSTRACT This essay is a study of how Jerome reads Jeremiah (Jer) 20:7-18. It presents the exegetical practice of Jerome within his Christian theological frame of reference and examines how he approaches a difficult text of the Old Testament (OT) as Christian Scripture. This essay is in five parts. The first briefly introduces the reader to Jer 20:7-18, sets the context for the importance of hearing premodern interpreters in contemporary biblical and theological scholarship, and presents a caveat to the reader with methodological issues. The second part focuses briefly on situating Jerome as a reader of Scripture within the general patristic exegesis, its interfaces between literal and allegorical modes of reading Scripture and how Jerome receives and modifies 1 Igor Pohl Baumann é doutorando em Teologia e Religião pela Universidade de Durham no Reino Unido (bolsista da CAPES). Mestre em Ciências da Religião pela Universidade Metodista de São Paulo e Bacharel em Teologia pela Faculdade Batista do Paraná. Este artigo constitui a versão parcial e revisada de um trabalho apresentado ao Departamento de Teologia e Religião da Universidade de Durham em 2016. Eu sou profundamente grato ao Professor Walter Moberly que cuidadosamente leu os rascunhos do material e fez valiosas sugestões para as primeiras versões. Também sou grato aos meus amigos Christopher Cho, Willibaldo Ruppenthal Neto e Caron Johnson pelos seus valorosos comentários, especialmente em relação à clarificação da expressão de meus pensamentos. -

Commentary on Jeremiah and Lamentations - Volume 3

Commentary on Jeremiah and Lamentations - Volume 3 Author(s): Calvin, John (1509-1564) (Alternative) (Translator) Publisher: Grand Rapids, MI: Christian Classics Ethereal Library Description: In this volume, John Calvin provides an engaging comment- ary on the book of Jeremiah and Lamentations. Originally given as a series of lectures, Calvin©s commentary is useful both for intellectual study and spiritual growth. Throughout, Calvin incorporates his keen pastoral insight. Utilizing other theologians and passages, Calvin attempts to provide new and fresh insights for readers. A commentary which has truly lasted the test of time, Calvin©s Commentary on Jeremiah and Lamentations is insightful, interesting, and profitable for study. Tim Perrine CCEL Staff Writer This volume contains Calvin©s commentary on Jeremiah, chapters 20 through 29. Subjects: The Bible Works about the Bible i Contents Commentary on Jeremiah 20-29 1 Translator's Preface 2 Chapter 20 9 Lecture seventy fifth 9 Jeremiah 20:1-2 10 Jeremiah 20:3 13 Jeremiah 20:4 16 Jeremiah 20:5 17 Prayer Lecture 75 18 Lecture seventy sixth 19 Jeremiah 20:6 20 Jeremiah 20:7 23 Jeremiah 20:8-9 27 Prayer Lecture 76 31 Lecture seventy seventh 32 Jeremiah 20:10 33 Jeremiah 20:11 35 Jeremiah 20:12 37 Jeremiah 20:13 40 Jeremiah 20:14-16 41 Prayer Lecture 77 44 Lecture seventy eighth 45 Jeremiah 20:17-18 47 Chapter 21 50 Jeremiah 21:1-4 51 Jeremiah 21:5 55 ii Prayer Lecture 78 57 Lecture seventy ninth 58 Jeremiah 21:6-7 59 Jeremiah 21:8-9 62 Jeremiah 21:10 65 Jeremiah 21:11-12 66 Prayer Lecture 79