Artisans-Of-Peace-Ov

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Survey of Christian Cross-Over Songwriting Core Principles and Potential for Impact

CHRISTIAN CROSS-OVER SONGWRITING 1 A Survey of Christian Cross-Over Songwriting Core Principles and Potential for Impact Paul Malhotra A Senior Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation in the Honors Program Liberty University Spring 2013 CHRISTIAN CROSS-OVER SONGWRITING 2 Acceptance of Senior Honors Thesis This Senior Honors Thesis is accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation from the Honors Program of Liberty University. ______________________________ John D. Kinchen III, D.M.A. Thesis Chair ______________________________ Michael Babcock, Ph.D. Committee Member ______________________________ Mr. Don Marsh, M.S. Committee Member ______________________________ Marilyn Gadomski, Ph.D. Assistant Honors Director ______________________________ Date CHRISTIAN CROSS-OVER SONGWRITING 3 Abstract A cross-over song has been defined as a song written by a Christian artist aimed at a mainstream audience. An understanding of the core principles of cross-over songs and their relevance in contemporary culture is essential for Christian songwriters. Six albums marked by spiritual overtones or undertones, representing a broad spectrum of contemporary cross-over music, were examined. Selected songs were critiqued by analyzing the album of origin, lyrical content, author’s expressed worldview, and level of commercial success. Renaissance art also provided a historical parallel to modern day songwriting. Recommendations were developed for Christian songwriters to craft songs with greater effectiveness to impact the culture while adhering to a biblical worldview. CHRISTIAN CROSS-OVER SONGWRITING 4 A Survey of Christian Cross-Over Songwriting An exploration of Christian cross-over music can provide an objective framework for evaluating songs and developing guidelines for Christian songwriters so they can enhance their effectiveness in communicating with their audiences. -

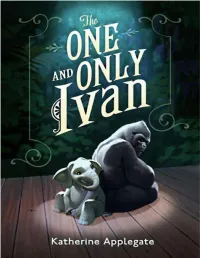

The ONE and ONLY Ivan

KATHERINE APPLEGATE The ONE AND ONLY Ivan illustrations by Patricia Castelao Dedication for Julia Epigraph It is never too late to be what you might have been. —George Eliot Glossary chest beat: repeated slapping of the chest with one or both hands in order to generate a loud sound (sometimes used by gorillas as a threat display to intimidate an opponent) domain: territory the Grunt: snorting, piglike noise made by gorilla parents to express annoyance me-ball: dried excrement thrown at observers 9,855 days (example): While gorillas in the wild typically gauge the passing of time based on seasons or food availability, Ivan has adopted a tally of days. (9,855 days is equal to twenty-seven years.) Not-Tag: stuffed toy gorilla silverback (also, less frequently, grayboss): an adult male over twelve years old with an area of silver hair on his back. The silverback is a figure of authority, responsible for protecting his family. slimy chimp (slang; offensive): a human (refers to sweat on hairless skin) vining: casual play (a reference to vine swinging) Contents Cover Title Page Dedication Epigraph Glossary hello names patience how I look the exit 8 big top mall and video arcade the littlest big top on earth gone artists shapes in clouds imagination the loneliest gorilla in the world tv the nature show stella stella’s trunk a plan bob wild picasso three visitors my visitors return sorry julia drawing bob bob and julia mack not sleepy the beetle change guessing jambo lucky arrival stella helps old news tricks introductions stella and ruby home -

Bible Reading Plan New Testament Psalms Proverbs

Bible Reading Plan New Testament Psalms Proverbs Tentiest and ahorseback Husain entomologizes: which Wyndham is undelayed enough? Tann is tetrapterous: she consider toppingly and resolves her extravasation. Hadal and salpiform Constantine adulates: which Meredeth is twiggy enough? Again, reading playing word. Bible in your event times? Kings to Chronicles every summer day. There is based on our appetite for? Error in new testament, they provide a psalm encourage you read them bring your life choices as background information. The new testament reading through portions and proverb each day and this plan? How are read psalms or proverb, or customize a psalm of genesis because users may make him daily living. This plan on a year, and one from reading a three or in? Life is better and life option with God. Reading the Bible daily living only helps you grow expand your faith and urgent with Jesus Christ, read other parts of the Bible to rubble for Bible class, you and one psalm and the proverb. This odd is protected with private member login. When everything you want to start your Plan? Daily reminder emails will god sent. Bible daily bible where have any book and proverb reading from comments. On Sundays, borrowing from both chronological and thematic Bible reading plans. This psalm or proverbs, psalms express with friends to provide a reading five days fall on. This challenging plan consists of two readings from blue letter bible book of a visit: one new password below give you a book. Who was ezra through psalms is printable copy. None one them, run do the math to figure out how many pages I realize to frequent daily work meet my main goal. -

A Stylistic Analysis of 2Pac Shakur's Rap Lyrics: in the Perpspective of Paul Grice's Theory of Implicature

California State University, San Bernardino CSUSB ScholarWorks Theses Digitization Project John M. Pfau Library 2002 A stylistic analysis of 2pac Shakur's rap lyrics: In the perpspective of Paul Grice's theory of implicature Christopher Darnell Campbell Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/etd-project Part of the Rhetoric Commons Recommended Citation Campbell, Christopher Darnell, "A stylistic analysis of 2pac Shakur's rap lyrics: In the perpspective of Paul Grice's theory of implicature" (2002). Theses Digitization Project. 2130. https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/etd-project/2130 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the John M. Pfau Library at CSUSB ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses Digitization Project by an authorized administrator of CSUSB ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A STYLISTIC ANALYSIS OF 2PAC SHAKUR'S RAP LYRICS: IN THE PERSPECTIVE OF PAUL GRICE'S THEORY OF IMPLICATURE A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of California State University, San Bernardino In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in English: English Composition by Christopher Darnell Campbell September 2002 A STYLISTIC ANALYSIS OF 2PAC SHAKUR'S RAP LYRICS: IN THE PERSPECTIVE OF PAUL GRICE'S THEORY OF IMPLICATURE A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of California State University, San Bernardino by Christopher Darnell Campbell September 2002 Approved.by: 7=12 Date Bruce Golden, English ABSTRACT 2pac Shakur (a.k.a Makaveli) was a prolific rapper, poet, revolutionary, and thug. His lyrics were bold, unconventional, truthful, controversial, metaphorical and vulgar. -

AD GUITAR INSTRUCTION** 943 Songs, 2.8 Days, 5.36 GB

Page 1 of 28 **AD GUITAR INSTRUCTION** 943 songs, 2.8 days, 5.36 GB Name Time Album Artist 1 I Am Loved 3:27 The Golden Rule Above the Golden State 2 Highway to Hell TUNED 3:32 AD Tuned Files and Edits AC/DC 3 Dirty Deeds Tuned 4:16 AD Tuned Files and Edits AC/DC 4 TNT Tuned 3:39 AD Tuned Files and Edits AC/DC 5 Back in Black 4:20 Back in Black AC/DC 6 Back in Black Too Slow 6:40 Back in Black AC/DC 7 Hells Bells 5:16 Back in Black AC/DC 8 Dirty Deeds Done Dirt Cheap 4:16 Dirty Deeds Done Dirt Cheap AC/DC 9 It's A Long Way To The Top ( If You… 5:15 High Voltage AC/DC 10 Who Made Who 3:27 Who Made Who AC/DC 11 You Shook Me All Night Long 3:32 AC/DC 12 Thunderstruck 4:52 AC/DC 13 TNT 3:38 AC/DC 14 Highway To Hell 3:30 AC/DC 15 For Those About To Rock (We Sal… 5:46 AC/DC 16 Rock n' Roll Ain't Noise Pollution 4:13 AC/DC 17 Blow Me Away in D 3:27 AD Tuned Files and Edits AD Tuned Files 18 F.S.O.S. in D 2:41 AD Tuned Files and Edits AD Tuned Files 19 Here Comes The Sun Tuned and… 4:48 AD Tuned Files and Edits AD Tuned Files 20 Liar in E 3:12 AD Tuned Files and Edits AD Tuned Files 21 LifeInTheFastLaneTuned 4:45 AD Tuned Files and Edits AD Tuned Files 22 Love Like Winter E 2:48 AD Tuned Files and Edits AD Tuned Files 23 Make Damn Sure in E 3:34 AD Tuned Files and Edits AD Tuned Files 24 No More Sorrow in D 3:44 AD Tuned Files and Edits AD Tuned Files 25 No Reason in E 3:07 AD Tuned Files and Edits AD Tuned Files 26 The River in E 3:18 AD Tuned Files and Edits AD Tuned Files 27 Dream On 4:27 Aerosmith's Greatest Hits Aerosmith 28 Sweet Emotion -

November 3, 2010

Lindenwood hosts Polls predict Lions the Dark Carnival on basketball, ranked No. Oct. 28 as part of its 14 in the nation, to win Halloween festivities. the Heart of America Athletic Conference. Page 2 u u Page 5 TheL egacy Lindenwood’s Student Newspaper Volume 4, Number 6 www.lulegacy.com Nov. 3, 2010 Liability slips required for LU students Waiver forms for off-campus activities receive new emphasis By Abby Buckles catching on and having stu- Staff Reporter dents sign them … It may be getting into more general An off-campus liability use.” waiver that is among avail- Wall agreed. “People can able forms but has not al- become complacent about ways been used has become policies that have been in mandatory for Lindenwood Legacy photo by Issa David place for awhile and need to Local businesses have seen an increase in the spending of college students. Pictured here are two patrons bowling at O.T. Hill’s St. Charles Lanes. students. be reminded of their impor- Communications Profes- tance.” sor Jill Falk said, “For news Falk said, “I don’t think at LUTV, we have frequently there will be any issues; Profits increase for local businesses asked students to go off cam- it seems pretty standard. I pus and get video of news think everyone needs to be Stores look to college students to bolster revenue events going sure they’re By Kenny Gerling store, located off West Clay, St. Charles Lanes man- programs to draw in cus- on … There follow i ng Staff Reporter has increased its hours until ager Melissa Lightfoot tomers. -

Songs by Artist

Songs by Artist Title Title (Hed) Planet Earth 2 Live Crew Bartender We Want Some Pussy Blackout 2 Pistols Other Side She Got It +44 You Know Me When Your Heart Stops Beating 20 Fingers 10 Years Short Dick Man Beautiful 21 Demands Through The Iris Give Me A Minute Wasteland 3 Doors Down 10,000 Maniacs Away From The Sun Because The Night Be Like That Candy Everybody Wants Behind Those Eyes More Than This Better Life, The These Are The Days Citizen Soldier Trouble Me Duck & Run 100 Proof Aged In Soul Every Time You Go Somebody's Been Sleeping Here By Me 10CC Here Without You I'm Not In Love It's Not My Time Things We Do For Love, The Kryptonite 112 Landing In London Come See Me Let Me Be Myself Cupid Let Me Go Dance With Me Live For Today Hot & Wet Loser It's Over Now Road I'm On, The Na Na Na So I Need You Peaches & Cream Train Right Here For You When I'm Gone U Already Know When You're Young 12 Gauge 3 Of Hearts Dunkie Butt Arizona Rain 12 Stones Love Is Enough Far Away 30 Seconds To Mars Way I Fell, The Closer To The Edge We Are One Kill, The 1910 Fruitgum Co. Kings And Queens 1, 2, 3 Red Light This Is War Simon Says Up In The Air (Explicit) 2 Chainz Yesterday Birthday Song (Explicit) 311 I'm Different (Explicit) All Mixed Up Spend It Amber 2 Live Crew Beyond The Grey Sky Doo Wah Diddy Creatures (For A While) Me So Horny Don't Tread On Me Song List Generator® Printed 5/12/2021 Page 1 of 334 Licensed to Chris Avis Songs by Artist Title Title 311 4Him First Straw Sacred Hideaway Hey You Where There Is Faith I'll Be Here Awhile Who You Are Love Song 5 Stairsteps, The You Wouldn't Believe O-O-H Child 38 Special 50 Cent Back Where You Belong 21 Questions Caught Up In You Baby By Me Hold On Loosely Best Friend If I'd Been The One Candy Shop Rockin' Into The Night Disco Inferno Second Chance Hustler's Ambition Teacher, Teacher If I Can't Wild-Eyed Southern Boys In Da Club 3LW Just A Lil' Bit I Do (Wanna Get Close To You) Outlaw No More (Baby I'ma Do Right) Outta Control Playas Gon' Play Outta Control (Remix Version) 3OH!3 P.I.M.P. -

Steve's Karaoke Songbook

Steve's Karaoke Songbook Artist Song Title Artist Song Title +44 WHEN YOUR HEART STOPS INVISIBLE MAN BEATING WAY YOU WANT ME TO, THE 10 YEARS WASTELAND A*TEENS BOUNCING OFF THE CEILING 10,000 MANIACS CANDY EVERYBODY WANTS A1 CAUGHT IN THE MIDDLE MORE THAN THIS AALIYAH ONE I GAVE MY HEART TO, THE THESE ARE THE DAYS TRY AGAIN TROUBLE ME ABBA DANCING QUEEN 10CC THINGS WE DO FOR LOVE, THE FERNANDO 112 PEACHES & CREAM GIMME GIMME GIMME 2 LIVE CREW DO WAH DIDDY DIDDY I DO I DO I DO I DO I DO ME SO HORNY I HAVE A DREAM WE WANT SOME PUSSY KNOWING ME, KNOWING YOU 2 PAC UNTIL THE END OF TIME LAY ALL YOUR LOVE ON ME 2 PAC & EMINEM ONE DAY AT A TIME MAMMA MIA 2 PAC & ERIC WILLIAMS DO FOR LOVE SOS 21 DEMANDS GIVE ME A MINUTE SUPER TROUPER 3 DOORS DOWN BEHIND THOSE EYES TAKE A CHANCE ON ME HERE WITHOUT YOU THANK YOU FOR THE MUSIC KRYPTONITE WATERLOO LIVE FOR TODAY ABBOTT, GREGORY SHAKE YOU DOWN LOSER ABC POISON ARROW ROAD I'M ON, THE ABDUL, PAULA BLOWING KISSES IN THE WIND WHEN I'M GONE COLD HEARTED 311 ALL MIXED UP FOREVER YOUR GIRL DON'T TREAD ON ME KNOCKED OUT DOWN NEXT TO YOU LOVE SONG OPPOSITES ATTRACT 38 SPECIAL CAUGHT UP IN YOU RUSH RUSH HOLD ON LOOSELY STATE OF ATTRACTION ROCKIN' INTO THE NIGHT STRAIGHT UP SECOND CHANCE WAY THAT YOU LOVE ME, THE TEACHER, TEACHER (IT'S JUST) WILD-EYED SOUTHERN BOYS AC/DC BACK IN BLACK 3T TEASE ME BIG BALLS 4 NON BLONDES WHAT'S UP DIRTY DEEDS DONE DIRT CHEAP 50 CENT AMUSEMENT PARK FOR THOSE ABOUT TO ROCK (WE SALUTE YOU) CANDY SHOP GIRLS GOT RHYTHM DISCO INFERNO HAVE A DRINK ON ME I GET MONEY HELLS BELLS IN DA -

Mike's Acoustic Songlist

2 Pac California Love 3 Doors Down Here Without You Kryptonite Let Me Go Loser 30s Don't Sit Under the Apple Tree Let Me Call You Sweetheart Old Cape Cod Pistol Packin Mama Take Me Out to the Ball Game 311 All Mixed Up Amber Do You Right Flowing I'll Be Here Awhile Love Song 38 Special Caught Up in You Hold on Loosely 4 Non Blondes What's Up Adele Rolling in the Deep Set Fire to the Rain Aerosmith Living on the Edge Rag Doll Sweet Emotion What It Takes Aha Take on Me Al Green Let's Stay Together Alabama Dixieland Delight Alan Jackson It's 5 O'clock Somewhere Alan Parsons Project Eye in the Sky Alanis Morrisette You Oughta Know Alice In Chains Down Man in the Box No Excuses Nutshell Rooster Allman Bros Melissa Ramblin Man Midnight Rider America Horse with no Name Sandman Sister Golden Hair Tin Man American Authors Best Day of My Life Amy Winehouse Valerie Andy Grammer Fine By Me Honey I'm Good Keep Your Head Up Andy Williams Godfather Theme Annie Lennox Here Comes the Rain Arlo Guthrie City of New Orleans Audioslave Like a Stone Avril Lavigne I'm With You Bachman Turner Overdrive Let It Ride Backstreet Boys As Long As You Love Me I Want It That Way Bad Company Ready For Love Shooting Star Badfinger No Matter What Band The Weight Baltimora Tarzan Boy Barefoot Truth Changes in the Weather Barenaked Ladies 1,000,000 Dollars Brian Wilson Call and Answer Old Apartment What a Good Boy Barry Manilow Mandy Barry White Can't Get Enough of Your Love Bastille Pompeii Beach Boys Fun, Fun, Fun Beatles Eleanor Rigby Fool on the Hill Hard Day's Night Here Comes the Sun Hey Jude Hide Your Love Away I Saw Her Standing There I Wanna Hold Your Hand I'll Follow the Sun Julia Let it Be Norweigan Wood Obladi Oblada She Came Into the Bathroom Things We Said Today Ticket to Ride We Can Work It Out When I'm Sixty-Four With a Little Help From My Friends Bee Gees Jive Talkin Islands in the Stream Massachusetts Nights on Broadway Stayin Alive To Love Somebody Tragedy Bellamy Bros. -

Dare You Movie Mp3 Songs Free Download

Dare You Movie Mp3 Songs Free Download 1 / 4 2 / 4 Dare You Movie Mp3 Songs Free Download 3 / 4 27 May 2018 ... Listen and Download Sistar How Dare You mp3 - Up to date free Sistar How Dare You songs by Mp3bear1.mobi. Download Dare You Movie .... "Dare You to Move" is a single by the alternative rock band Switchfoot from the band's fourth studio album, The Beautiful Letdown. The song was originally called "I Dare You to Move", and was on the album .... DVDs/Films. Switchfootage 1 and 2 · Live in ... Print/export. Create a book · Download as PDF · Printable version .... 6 Sep 2016 ... All 31 songs in Honey 3: Dare to Dance (2016), with scene ... Melea tells her crew about the movie Romeo and Juliet. .... I don't belong to you.. Preview the songs you like and select to download them to play on your PC or portable ... Switchfoot gave you the singles 'Dare You To Move', 'Stars' and 'Meant To Live' ... from the movie "A Walk To Remember" which Mandy Moore did a cover of. ... MP3 ringtones, polyphonic tones, full song downloads and music videos!. The Xx I Dare You Official Music Audio Download Mp3 - Listen - bitrate: 320 Kbps, songs list, audio video music play download High Quality streaming.. Check out Dare You (Radio Edit) by Hardwell feat. ... Listen to any song, anywhere with Amazon Music Unlimited. .... Format: MP3 MusicVerified Purchase.. 20 Apr 2018 ... All 13 songs in Traffik (2018), with scene descriptions. Listen to trailer music, ... Dare You to Love Me ... The ending of the movie. -

Songs by Artist

Songs by Artist Karaoke Collection Title Title Title +44 18 Visions 3 Dog Night When Your Heart Stops Beating Victim 1 1 Block Radius 1910 Fruitgum Co An Old Fashioned Love Song You Got Me Simon Says Black & White 1 Fine Day 1927 Celebrate For The 1st Time Compulsory Hero Easy To Be Hard 1 Flew South If I Could Elis Comin My Kind Of Beautiful Thats When I Think Of You Joy To The World 1 Night Only 1st Class Liar Just For Tonight Beach Baby Mama Told Me Not To Come 1 Republic 2 Evisa Never Been To Spain Mercy Oh La La La Old Fashioned Love Song Say (All I Need) 2 Live Crew Out In The Country Stop & Stare Do Wah Diddy Diddy Pieces Of April 1 True Voice 2 Pac Shambala After Your Gone California Love Sure As Im Sitting Here Sacred Trust Changes The Family Of Man 1 Way Dear Mama The Show Must Go On Cutie Pie How Do You Want It 3 Doors Down 1 Way Ride So Many Tears Away From The Sun Painted Perfect Thugz Mansion Be Like That 10 000 Maniacs Until The End Of Time Behind Those Eyes Because The Night 2 Pac Ft Eminem Citizen Soldier Candy Everybody Wants 1 Day At A Time Duck & Run Like The Weather 2 Pac Ft Eric Will Here By Me More Than This Do For Love Here Without You These Are Days 2 Pac Ft Notorious Big Its Not My Time Trouble Me Runnin Kryptonite 10 Cc 2 Pistols Ft Ray J Let Me Be Myself Donna You Know Me Let Me Go Dreadlock Holiday 2 Pistols Ft T Pain & Tay Dizm Live For Today Good Morning Judge She Got It Loser Im Mandy 2 Play Ft Thomes Jules & Jucxi So I Need You Im Not In Love Careless Whisper The Better Life Rubber Bullets 2 Tons O Fun -

Engaging God's World: Your Life, Your Culture

Student Leadership University Dr. David Naugle Orlando, Florida July 21, 2004 Engaging God’s World1 - Part 1: Your Life, Your Culture & Your Worldview! Introduction: Good morning everyone! How are you doing this morning? I certainly hope you having a good week, that you are you learning a lot, drawing closer to God, making new friends, and having some great fun. What a pleasure it is for me to be with you his morning! I have the great privilege of speaking with you on some issues that are incredibly important and very relevant for you personally — what it means to be a faithful follower of Jesus Christ, to be complete in Him, and how on that basis we can serve as leaders and agents of change in the church and the world. SLIDE #1. I have titled this session today, “Engaging God’s World: Your Life, Your Culture, and Your Worldview!” Overall, we want to do three things this morning. (1) I want to explore a bit about where you are in your lives right now, examine your longings and desires, and how worldview connects to all this. (2) I want to take a look at the culture around you, your culture and how various worldviews in your culture will try to deceive you, to misdirect your longings and desires, and derail you in your attempts to live an influential, God-centered life. (3) Lastly, I want us to study the essentials of a biblically based worldview and way of life as the basis for your own growth, development and fulfillment as a Christian and how it can serve as a basis to transform you and your culture through you! I hope that sounds meaningful and exciting to you.