Chase Barrett

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Travelin' Grampa

The Travelin’ Grampa Touring the U.S.A. without an automobile Focus on safe, fast, convenient, comfortable, cheap travel, via public transit. Music Festivals Supplement Vol. 10, No. 7, July 2017 Photo credit: Red Frog Events, Firefly Music Festival. Firefly Music Festival 2017 in Dover, Delaware, reached by DART #301 bus, is said to have attracted 90,000 fans. It’s time again to ride a bus, or train, to a music festival Dozens of multi-day music festivals beckon during summer 2017. Ranging from psychedelically spotlighted rock music events, where performers and audience both jump around and wave their hands into the air, to those where the audience sits quietly as a full-fledged symphony orchestra plays classical music, many, if not most, of them are readily reachable by public transportation. The following pages of this special Music Festival Supplement focus on popular jazz, rock and classical music festivals and how to get to them via public transportation. Getting particular attention is the Firefly Music Festival, a four-day rock music fest in Dover, Delaware, attended by Grampa, who rode there by SEPTA train and DART First State bus. Photo credit: Town of Vail, Colorado. Telluride Chamber Music Festival symphony orchestra performance at Sheridan Opera House, Telluride, Colo. 1 . The Travelin’ Grampa Music Festivals Supplement . Here are a few Summer 17 classical music festivals: Telluride Chamber Music Festival, Sheridan Opera House Telluride, Colo., Aug. 10-13, has since 1973 specialized in presenting high quality small-ensemble performances of classical music of such composers as Brahms, Dvořák and Mozart. Galloping Goose Transit, a free bus system, services riders in the Town of Telluride and adjoining San Miguel County communities. -

Psychedelia, the Summer of Love, & Monterey-The Rock Culture of 1967

Trinity College Trinity College Digital Repository Senior Theses and Projects Student Scholarship Spring 2012 Psychedelia, the Summer of Love, & Monterey-The Rock Culture of 1967 James M. Maynard Trinity College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.trincoll.edu/theses Part of the American Film Studies Commons, American Literature Commons, and the American Popular Culture Commons Recommended Citation Maynard, James M., "Psychedelia, the Summer of Love, & Monterey-The Rock Culture of 1967". Senior Theses, Trinity College, Hartford, CT 2012. Trinity College Digital Repository, https://digitalrepository.trincoll.edu/theses/170 Psychedelia, the Summer of Love, & Monterey-The Rock Culture of 1967 Jamie Maynard American Studies Program Senior Thesis Advisor: Louis P. Masur Spring 2012 1 Table of Contents Introduction..…………………………………………………………………………………4 Chapter One: Developing the niche for rock culture & Monterey as a “savior” of Avant- Garde ideals…………………………………………………………………………………...7 Chapter Two: Building the rock “umbrella” & the “Hippie Aesthetic”……………………24 Chapter Three: The Yin & Yang of early hippie rock & culture—developing the San Francisco rock scene…………………………………………………………………………53 Chapter Four: The British sound, acid rock “unpacked” & the countercultural Mecca of Haight-Ashbury………………………………………………………………………………71 Chapter Five: From whisperings of a revolution to a revolution of 100,000 strong— Monterey Pop………………………………………………………………………………...97 Conclusion: The legacy of rock-culture in 1967 and onward……………………………...123 Bibliography……………………………………………………………………………….128 Acknowledgements………………………………………………………………………..131 2 For Louis P. Masur and Scott Gac- The best music is essentially there to provide you something to face the world with -The Boss 3 Introduction: “Music is prophetic. It has always been in its essence a herald of times to come. Music is more than an object of study: it is a way of perceiving the world. -

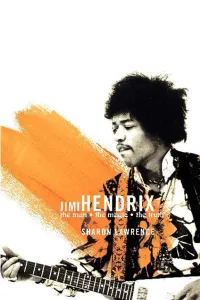

Sharon20lawrence20-20Jimi20hendrix20the20man2c20the20magic2c20the20truth

Jimi Hendrix THE MAGIC, THE MAN, THE TRUTH SHARON LAWRENCE Technically, I’m not a guitar player.AllIplayistruthandemotion. —JIMI H ENDRIX Contents Prologue.....v PART ONE: A BOY-CHILD COMIN’ ONE......Johnny/Jimmy.....3 TWO.....Don’tLookBack.....9 THREE.....FlyingHigh.....21 FOUR.....TheStruggle.....27 PART TWO: LONDON, PARIS, THE WORLD! FIVE.....ThrillingTimes.....47 SIX.....“TheBestYearofMyLife”.....69 SEVEN.....Experienced.....91 EIGHT.....AllAlongtheWatchtower.....119 NINE.....TheTrial.....159 TEN.....Drifting.....175 ELEVEN.....PurpleHaze.....189 TWELVE.....InsidetheDangerZone.....207 Coda.....217 Contents PART THREE: THE REINVENTION OF JIMI HENDRIX INTRODUCTION.....229 THIRTEEN.....1971–1989:TheNewRegime.....231 FOURTEEN.....1990–1999:ASeriesofShowdowns.....247 FIFTEEN.....2000–2004:Wealth,Power,and ReflectedGlory.....271 PART FOUR: THE TRUE LEGACY.....319 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS.....337 ABOUT THE AUTHOR CREDITS COVER COPYRIGHT ABOUT THE PUBLISHER IV PROLOGUE F EBRUARY 9,1968 Iobservedtheextravagantaureoleofcarefullyteasedblackhair.The face,withitsluminousbrowneyeslookingdirectlyatme,wasgentle. His handshake was firm. He smiled warmly, respectfully even, and saidinalow,whisperyvoice,“Thanksforcomingouttonight.” SothiswasJimiHendrix.TheexoticphotographsI’dseeninthe English music papers offered a somewhat terrifying image. On this night,though,Imetashy,politehumanbeing. “Sharon,”LesliePerrin hadsaidon thetelephone,“I’vejustar- rivedfromLondon,andI’dliketointroduceyoutoJimiHendrix.He’s veryspecial.Andhe’splayingnearDisneylandtonight!” ForyearsLesliePerrinhadbeenafigureinLondonpressandmu- -

Book Review with TTU Libraries Cover Page (746.4Kb)

BOOK REVIEW OF "THE GRATEFUL DEAD" The Texas Tech community has made this publication openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters to us. Citation Weiner, R.G. (1997). [Review of the book The Grateful Dead by Goldberg, Christine]. Journal of Popular Culture, 31(1), 215-217. Citable Link http://hdl.handle.net/2346/1542 Terms of Use CC-BY Title page template design credit to Harvard DASH. Book Reviews . 215 lack sufficient empirical corroboration; however, the essay format of his expose offers him more freedom in this regard. Maase also has a ten dency to argue in a quasi-teleological way, suggesting that all develop ments within European popular culture were ultimately targeted at the basic cultural shift that he recognizes. This reader would have welcomed a more elaborate annotation, although this is partially compensated by the selected bibliography at the end. Also disappointing is the lack of an index in a work with such scholarly pretensions. Nevertheless, the book makes a valuable contribution to our understanding of European popular culture. The publisher should seriously consider an English translation, in order to reach a much broader, international audience. Tilburg University, The Netherlands Mel van Elteren Chelsea House Publisher's newest addition to their Pop Culture Legends Series (which includes books on Marilyn Monroe, Madonna, Stephen King, and Bruce Springsteen, among others) is a short history of the leg endary Grateful Dead (GO). These books, designed for young adult readers and the general public, provide a unique perspective on popular culture icons. Scholars of Popular Culture can study and analyze books like these in order to have a greater understanding of how such figures fit into the popular milieu and mindset of our culture. -

The Grateful Dead

You should be able to answer these questions about the counterculture: 1. How did the countercultural movement come about? 2. Who were some people/bands associated with this movement? 3. How was the album St. Pepper important to psychedlic music? 4. What is the significance of LSD and the Acid Tests? 5. What were the criticisms against the counterculture? Especially focus on the comments made in the “Hippie Temptation.” 6. Why is California significant at this time? The Counterculture, Psychedelic Rock, and Subculture Counterculture What shaped the counterculture? 1. mixing of Christian brotherhood (“love thy neighbor”) and Eastern philosophy/religion and music 2. mass availability to birth control (the pill) 3. escalation of the Vietnam War 4. music= acid/psychedelic rock all was tied together with the use of mind-altering drugs The countercultural movement was a move away !om conventional society and an adoption of the idea of !ee-living and !ee-loving. Not everyone was into “ee-love$ esp. parents and the government. Counterculture primarily developed in San Francisco One band associated with the movement was the Grateful Dead: • lived in Haight-Ashbury • started out as a jug band • played for Acid Tests (as Warlocks) • synaesthesia-- mixed senses= hearing colors, tasting sounds sometimes a side effect of LSD • the music they played at the acid tests consisted of long improvised blues, they continue to play this type of music, known as a jam band Grateful Dead, cont. -- their performances, which were very communal, exemplified the countercultural ideology of free love -- they continued to foster this since of community long after the countercultural movement died down -- this is exemplified in their fostering a strong subculture through: -- free taping and sharing of live concerts -- the development of specific symbols: skull and lightening, the dancing bears, tie-dye shirts -- they established a fan club and gave them a name, “Dead Heads” -- always playing different songs at shows The Beatle’s St. -

Starr-Waterman American Popular Music Chapter 10: “Blowin' in The

Starr-Waterman American Popular Music Chapter 10: “Blowin’ in the Wind”: Country, Soul, Urban Folk, and the Rise of Rock, 1960s Filmography The Doors (1991): Val Kilmer stars in this Oliver Stone–directed biopic about Jim Morrison, the lead singer for the influential rock band the Doors. Fiddler on the Roof (1971): Movie version of the long-running Broadway musical with a bestselling Broadway cast album and bestselling soundtrack. Fly Jefferson Airplane (2004): Focusing on the bands activities during the late 1960s and early 1970s, this film features interviews with band members and live concert footage. Gimmie Shelter (1970): Documented a free concert at the Altamont Speedway in California at which members of the Hell’s Angels motorcycle gang, who had been hired to provide security for the event, killed a young black man named Meredith Hunter. The Grateful Dead Movie (1977): This film (directed by Jerry Garcia) includes a performance at the Winterland Ballroom in San Francisco and captures the “Deadhead” atmosphere and community. Monterey Pop (1968): This documentary is about the 1967 Monterey Pop Festival featuring Janis Joplin, the Who, Otis Redding, Ravi Shankar, and others, including Jimi Hendrix, who famously lit his guitar on fire. The Night James Brown Saved Boston (2008): Alternating among concert clips, media commentary, and eyewitness interviews, this film explores James Brown’s role in saving Boston from the kind of upheaval other major cities faced in the aftermath of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination. Respect Yourself: The Stax Records Story (2007): Told from the part of the musicians (including the house band led by Booker T. -

Open-Air-Festival-Kultur

Open-Air-Festival-Kultur «Open-Air-Festivals» sind heute in der Schweiz die grössten kulturellen Veranstaltungen überhaupt. Kein anderes Land weist eine ähnliche Dichte an «Open-Air- Festivals» mit europaweitem Ruf auf. Jeden Sommer pilgern tausende meist Jugendliche und junge Erwach- sene, je nach Musikangebot aber auch ganze Familien, zu den ein- oder mehrtägigen Konzertveranstaltungen im Freien. Für die Zeit des Aufenthaltes verlässt man das Festivalgelände in der Regel nicht. Die Besucherin- nen und Besucher bringen alles Nötige mit. Sie über- nachten in Zelten, doch geschlafen wird dabei nur we- nig. Die «Open-Air-Festivals» sind riesige mehrtätige «Partys» und für viele junge Menschen prägende Erleb- Paléo Nyon (© Paléo Nyon / Marc Amiguet) nisse. Verbreitung Schweiz Bereiche Darstellende Künste Gesellschaftliche Praktiken Version Juni 2018 Autoren Johannes Rühl, Peter Hummel, Ariane Devanthéry, Regula Steiner Die Liste der lebendigen Traditionen in der Schweiz sensibilisiert für kulturelle Praktiken und deren Vermittlung. Ihre Grundlage ist das UNESCO-Übereinkommen zur Bewahrung des immateriellen Kulturerbes. Die Liste wird in Zusammenarbeit und mit Unterstützung der kantonalen Kulturstellen erstellt und geführt. Ein Projekt von: Unüberschaubar gross erscheint heute die Zahl der das zweite «British Rock Meeting» in Germersheim jährlich stattfindenden «Open-Air-Festivals», von denen (1972). Mit den Jahren hat sich das Angebot der Festi- einige zu den grössten kulturellen Veranstaltungen in vals immer wieder verändert und fortwährend dem wan- der Schweiz gehören. Kein anderes Land weist eine delnden Musikgeschmack angepasst. Auch in der ähnliche Dichte an «Open-Air-Festivals» mit europawei- Schweiz überwog nach den Anfängen mit Folk und tem Ruf auf. Jeden Sommer pilgern tausende Jugendli- Rock zunehmend Punk, Hardrock und immer mehr der che und junge Erwachsene, je nach Angebot auch Mainstream-Pop. -

TAKE YOU? W Oodstock Are Usually Snapped up Festival , Within Minutes of Them 1969, Is Seen As the Going on Sale Each Benchmark for Music Year

Culture Music festivals around the world 1 Work with a partner. Look at the infographic The US Brazil The US and answer the questions. Coachella Rock in Rio Summerfest 1 What are the things that attract people to festivals? 675,000 700,000 800,000-1m 2 Do you find any of the numbers surprising? Why/Why not? 2a Read about the history of festivals and some Morocco Austria different festivals held today. Which countries are Mawazine Donauinselfest the different festivals mentioned held in? 2.5 million 3.3 million Where will the music TAKE YOU? W oodstock are usually snapped up Festival , within minutes of them 1969, is seen as the going on sale each benchmark for music year. festivals, but over a decade Moving across earlier Newport Jazz Festival the Atlantic, is the was evolving into what would Bahidorá festival become a major event. in Mexico. A much The Monterey Pop Festival, in younger festival than 1967, was where names like the likes of Glastonbury, Janis Joplin and Jimi it has attracted good line- ups of local and international Hendrix became big and helped performers and a good crowd to start shaping of around 6,000, mostly Mexicans, music history. And for the few years it’s been running. It’s also then there was one a shorter festival. It starts on a Saturday awarded Best Major European Festival at of the biggest events morning and sadly, by the Sunday evening, the European Festival Awards in 2014, a in music history with its it’s all over. surprising accomplishment after starting out as a student-initiated project. -

Musicians with Complex Racial Identifications in Mid-Twentieth Century American Society

“CASTLES MADE OF SAND”: MUSICIANS WITH COMPLEX RACIAL IDENTIFICATIONS IN MID-TWENTIETH CENTURY AMERICAN SOCIETY by Samuel F.H. Schaefer A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in Public History Middle Tennessee State University December 2018 Thesis Committee: Dr. Kristine McCusker, Chair Dr. Brenden Martin To my grandparents and parents, for the values of love and empathy they passed on, the rich cultures and history to which they introduced me, for modeling the beauty of storytelling, and for the encouragement always to question. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS For serving on my committee, encouraging me to follow my interests in the historical record, great patience, and for invaluable insights and guidance, I would like to thank Dr. Brenden Martin and especially Dr. Kristine McCusker, my advisor. I would also like to thank Dr. Thomas Bynum and Dr. Louis Woods for valuable feedback on early drafts of work that became part of this thesis and for facilitating wonderful classes with enlightening discussions. In addition, my sincere thanks are owed to Kelle Knight and Tracie Ingram for their assistance navigating the administrative requirements of graduate school and this thesis. For helpful feedback and encouragement of early ideas for this work, I thank Dr. Walter Johnson and Dr. Charles Shindo for their commentary at conferences put on by the Louisiana State University History Graduate Student Association, whom I also owe my gratitude for granting me a platform to exchange ideas with peers. In addition, I am grateful for the opportunities extended to me at the National Museum of African American Music, the Musicians Hall of Fame and Museum, and the Center for Popular Music, which all greatly assisted in this work’s development. -

![Sadler's Wells Theatre, London, England (FM)[MP3-320];124 514 KB](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9839/sadlers-wells-theatre-london-england-fm-mp3-320-124-514-kb-3039839.webp)

Sadler's Wells Theatre, London, England (FM)[MP3-320];124 514 KB

10,000 Maniacs;1988-07-31;Sadler's Wells Theatre, London, England (FM)[MP3-320];124 514 KB 10,000 Maniacs;Eden's Children, The Greek Theatre, Los Angeles, California, USA (SBD)[MP3-224];150 577 KB 10.000 Maniacs;1993-02-17;Berkeley Community Theater, Berkeley, CA (SBD)[FLAC];550 167 KB 10cc;1983-09-30;Ahoy Rotterdam, The Netherlands [FLAC];398 014 KB 10cc;2015-01-24;Billboard Live Tokyo, Tokyo, Japan [MP3-320];173 461 KB 10cc;2015-02-17;Cardiff, Wales (AUD)[FLAC];666 150 KB 16 Horsepower;1998-10-17;Congresgebow, The Hague, Netherlands (AUD)[FLAC];371 885 KB 16 Horsepower;2000-03-23;Eindhoven, Netherlands (Songhunter)[FLAC];514 685 KB 16 Horsepower;2000-07-31;Exzellenzhaus, Sommerbühne, Germany (AUD)[FLAC];477 506 KB 16 Horsepower;2000-08-02;Centralstation, Darmstadt, Germany (SBD)[FLAC];435 646 KB 1975, The;2013-09-08;iTunes Festival, London, England (SBD)[MP3-320];96 369 KB 1975, The;2014-04-13;Coachella Valley Music & Arts Festival (SBD)[MP3-320];104 245 KB 1984;(Brian May)[MP3-320];80 253 KB 2 Live Crew;1990-11-17;The Vertigo, Los Angeles, CA (AUD)[MP3-192];79 191 KB 21ST CENTURY SCHIZOID BAND;21st Century Schizoid Band;2002-10-01;Queen Elizabeth Hall, London, England [FLAC];619 21ST CENTURY SCHIZOID BAND;21st Century Schizoid Band;2004-04-29;The Key Club, Hollywood, CA [MP3-192];174 650 KB 2wo;1998-05-23;Float Right Park, Sommerset, WI;Live Piggyride (SBD)(DVD Audio Rip)[MP3-320];80 795 KB 3 Days Grace;2010-05-22;Crew Stadium , Rock On The Range, Columbus, Ohio, USA [MP3-192];87 645 KB 311;1996-05-26;Millenium Center, Winston-Salem, -

The Acid King Without the Little-Known Éminence Grise of LSD, Owsley Stanley III, ‘The Sixties’ Might Never Have Happened

LSD THE ACID KING Without the little-known éminence grise of LSD, Owsley Stanley III, ‘the sixties’ might never have happened. By Andy Roberts On March 12, 2011, a 76-year old man Ginsberg took the drug as part of a that LSD chemistry was nearer to acid drove his car into a ditch, in a remote federally funded volunteer programme. alchemy. part of Queensland, Australia, killing But it was never clear what drug they Owsley’s fame spread and he met himself and injuring his wife. In the were being given or at what dosages. up with author and Merry Prankster years leading up to his death, Owsley Ken Kesey and began supplying Kesey’s Stanley had become a reclusive, i wound up doing notorious Acid Tests, LSD consumed in semi-mythical figure, refusing to give orange juice, famously chronicled by Tom interviews and rarely photographed. time for something Wolfe. But while Kesey and his cohorts Why the media interest? Because i should have been wanted to be as stoned as possible on Owsley Stanley was the world’s first high dose LSD, Owsley knew they were underground chemist, the first person rewarded for. playing a dangerous game. Equating to produce LSD outside the laboratory what i did was a the acid trip with the altered states of and the man who dosed the psychedelic consciousness associated with magical revolution. community service, rituals, he said to Kesey, “you guys are Despite a prestigious background the way i look at it fucking around with something people – his grandfather was Kentucky State have known about forever…All the Governor and a Democratic senator, occult literature about ceremonial magic his father a lawyer – Owsley’s family Owsley decided the only way to ensure warns about being very careful when you life was troubled. -

1967: a Year in the Life of the Beatles

1967: A Year In The Life Of The Beatles History, Subjectivity, Music Linda Engebråten Masteroppgave ved Institutt for Musikkvitenskap UNIVERSITETET I OSLO November 2010 Acknowledgements First, I would like to express my gratitude towards my supervisor Stan Hawkins for all his knowledge, support, enthusiasm, and his constructive feedback for my project. We have had many rewarding discussions but we have also shared a few laughs about that special music and time I have been working on. I would also like to thank my fellow master students for both useful academically discussions as much as the more silly music jokes and casual conversations. Many thanks also to Joel F. Glazier and Nancy Cameron for helping me with my English. I thank John, Paul, George, and Ringo for all their great music and for perhaps being the main reason I begun having such a big interest and passion for music, and without whom I may not have pursued a career in a musical direction at all. Many thanks and all my loving to Joakim Krane Bech for all the support and for being so patient with me during the course of this process. Finally, I would like to thank my closest ones: my wonderful and supportive family who have never stopped believing in me. This thesis is dedicated to my grandparents. There are places I'll remember All my life though some have changed. Some forever not for better Some have gone and some remain. All these places have their moments With lovers and friends I still can recall. Some are dead and some are living, In my life I've loved them all.