Chew Magna Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lake View Chew Stoke, BS40 8XJ

Lake View Chew Stoke, BS40 8XJ Lake View DESCRIPTION The first floor is equally as good! Lake View comprises four Boasting spacious and flexible accommodation, stunning double bedrooms of very good sizes, which all enjoy their Stoke Hill gardens and beautiful views, swimming pool, paddock and own unique outlooks over the property’ s grounds and further orchard... Lake View really is a must see for any buyer countryside beyond. Two of the double rooms benefit from Chew Stoke looking to engross themselves within the Chew Valley their own ensuite shower room and the other two rooms are community. The property occu pies a large level plot that sits currently furnished by a modern four piece family bathroom. BS40 8XJ on the fringe of Chew Stoke village , perfect for any The current master bedroom is of a very good size and homeowner who is looking for links back to the nearby cities already has t he plumbing in place for a new owner to put in of Bristol, Bath and Wells. an ensuite facility if they desire. • Stunning detached residence The property itself is entered at the front into a beautiful The gardens and grounds at Lake View are truly stunning. The • Exceptional grounds open plan sitting room and large dining room. The sitting gardens wrap around the property to both the front and rear room features a stone fireplace with inset log burner and the and are predominantly laid to lawn but also featur e various • Spacious and flexible accommodation dining area at the back of the room enjoys a pleasant view seating areas which are perfect for alfresco dining. -

Records of Bristol Cathedral

BRISTOL RECORD SOCIETY’S PUBLICATIONS General Editors: MADGE DRESSER PETER FLEMING ROGER LEECH VOL. 59 RECORDS OF BRISTOL CATHEDRAL 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 RECORDS OF BRISTOL CATHEDRAL EDITED BY JOSEPH BETTEY Published by BRISTOL RECORD SOCIETY 2007 1 ISBN 978 0 901538 29 1 2 © Copyright Joseph Bettey 3 4 No part of this volume may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, 5 electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any other information 6 storage or retrieval system. 7 8 The Bristol Record Society acknowledges with thanks the continued support of Bristol 9 City Council, the University of the West of England, the University of Bristol, the Bristol 10 Record Office, the Bristol and West Building Society and the Society of Merchant 11 Venturers. 12 13 BRISTOL RECORD SOCIETY 14 President: The Lord Mayor of Bristol 15 General Editors: Madge Dresser, M.Sc., P.G.Dip RFT, FRHS 16 Peter Fleming, Ph.D. 17 Roger Leech, M.A., Ph.D., FSA, MIFA 18 Secretaries: Madge Dresser and Peter Fleming 19 Treasurer: Mr William Evans 20 21 The Society exists to encourage the preservation, study and publication of documents 22 relating to the history of Bristol, and since its foundation in 1929 has published fifty-nine 23 major volumes of historic documents concerning the city. -

Spring Farm Spring Lane, East Dundry, Bristol, BS41 8NT

SPRING FARM SPRING LANE, EAST DUNDRY, BRISTOL, BS41 8NT SPRING FARM Gross internal area (approx.) 283 sq m / 3046 sq ft Utility = 7 sq m / 75 sq ft Store = 14 sq m / 151 sq ft Total = 304 sq m / 3272 sq ft Outbuilding Lower Ground Floor Ground Floor Savills Clifton Second Floor 20 The Mall First Floor Clifton Village Bristol BS8 4DR For identification purposes only - not to scale [email protected] 0117 933 5800 Important Notice Savills, their clients and any joint agents give notice that: 1. They are not authorised to make or give any representations or warranties in relation to the property either here or elsewhere, either on their own behalf or on behalf of their client or otherwise. They assume no responsibility for any statement that may be made in these particulars. These particulars do not form part of any offer or contract and must not be relied upon as statements or representations of fact. 2. Any areas, measurements or distances are approximate. The text, photographs and plans are for guidance only and are not necessarily comprehensive. It should not be assumed that the property has all necessary planning, building regulation or other consents and Savills have not tested any services, equipment or facilities. Purchasers must satisfy themselves by inspection or otherwise. SPRING FARM SPRING LANE, EAST DUNDRY, BRISTOL, BS41 8NT A beautiful restored farmhouse with exquisite country views • Detached period farmhouse • Three reception rooms • Kitchen and separate utility • Five bedrooms • Two bathrooms • Private hillside location -

Sol\!ERSET I [KELLY'8 T

• • • SOl\!ERSET I [KELLY'8 t . • Mellor .Alfred Somerville Arthur Fownes LL.B. (deputy chairman of Middleton Charles Marmaduke quarter sessions), Dinder house, Wells *Mildmay Capt. Charles Beague St. John- R.A. Hollam, Southcombe Sidney Lincoln, Highlands, .A.sh, Martock Dulverton Sparkes SI. Harford, Wardleworth, Tonedale, Wellingtn Mildmay Capt. Wyndham Paulet St. John . *Speke Col. Waiter Hanning, Jordans, Ilminster Miller John Reynolds, Haworth, High street, WellinO'ton Spencer Huntly Gordon l\Iinifie Mark, 27 Montpelier, Weston-super-Mare "' Staley Alfd. Evelyn, Combe Hill,Barton St.David,Tauntn l\Ioore Col. Henry, Higher W oodcomhe, Minehead Stanley Edward Arthur Vesey, Quantock lodge, Over Morland John, Wyrral, Glastonbury Stowey, Bridgwater 1\forland John Coleby, Ynyswytryn, Glastonbury Stanley James Talbot Mountst•even Col. Francis Render C.M.G. Odgest, Ston Staunton-Wing George Stauntoll, Fitzhead court,Tauntn Easton, Bath Stead Maurice Henry, St. Dunstan's, Magdalene street, Murray-Anderdon Henry Edward, Henlade ho. Taunton Glastonbury *Napier Lieut.-Col. Gerard Berkeley, Pennard house, Stenhouse Col. Vivian Denman, Netherleigh, Blenheim Shepton Mallet ' road, :M:inehead Napier Henry Burroughes, Hobwell,Long Ashton,Bristol Stothert Sir Percy Kendall K.B.E. Woolley grange, Nathan Lieut.-Col. Right Hon. Sir Matthew G.C.M.G., Bradford-on-Avon, Wilts R.E., K 2 & 4 Albany, London W I Strachey Capt. Hon. Edward, Sutton court, Pensford, Naylor James Richard C.S.I. Hallatrow court, Bristol Bristol Neville Adm.Sir George K.C.B., C.V.O. Babington house, Strachey Richard Sholto, .Ashwick grove, Oakhill, Bath near Bath ' *Strachie Lord, Sutton court, Pensford, Bristol; & 27 *~e~ille Grenville Robert, Bntleigh court, Glastonbury Cadogan gardens, London SW 3 . -

Flood Risk Reduction

Introduction to Payments for Ecosystem Services Dr. Bruce Howard (Co-ordinator EKN) & Dr. Chris Sherrington (Principal Consultant, Eunomia) What Are Ecosystem Services? • Benefits we derive from the natural environment • Provision of: • Food, water, timber What Are Ecosystem Services? • Benefits we derive from the natural environment • Regulation of: • Air quality, climate, flood risk What Are Ecosystem Services? • Benefits we derive from the natural environment • Cultural Services: • Recreation, tourism, education What Are Ecosystem Services? • Benefits we derive from the natural environment • Supporting Services: • Soil formation, nutrient cycling Payments for Ecosystem Services PES Principles • Voluntary • Stakeholders enter into PES agreements on a voluntary basis • Additionality • Payments are made for actions over and above those which land managers would generally be expected to undertake Bundling and Layering • Bundling • A single buyer pays for the full package of ecosystem services • E.g. agri-environment scheme delivering landscape, water quality etc. on behalf of public • Layering • Multiple buyers pay separately for different ecosystem services from same parcel of land • E.g. peatland benefits of carbon sequestration, water quality and flood risk management may be purchased by different buyers Payments for Ecosystem Services UK interest in PES PES timeline 1990 New York Long-term Watershed Protection Vittel, NE France Costa Rica forest protection 2000 UK - Visitor Payback schemes UK - United Utilities SCaMP1 2010 UK - Exploratory -

Chew Magna and Stanton Drew

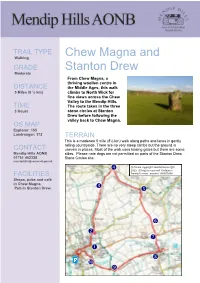

TRAIL TYPE Chew Magna and Walking GRADE Stanton Drew Moderate From Chew Magna, a thriving woollen centre in DISTANCE the Middle Ages, this walk 5 Miles (8 ½ km) climbs to North Wick for fine views across the Chew Valley to the Mendip Hills. TIME The route takes in the three 3 Hours stone circles at Stanton Drew before following the valley back to Chew Magna. OS MAP Explorer: 155 Landranger: 172 TERRAIN This is a moderate 5 mile (8½ km) walk along paths and lanes in gently rolling countryside. There are no very steep climbs but the ground is CONTACT uneven in places. Most of the walk uses kissing gates but there are some Mendip Hills AONB stiles. Please note dogs are not permitted on parts of the Stanton Drew 01761 462338 Stone Circles site. [email protected] © Crown copyright and database right 2015. All rights reserved. Ordnance Survey License number 100052600 FACILITIES Shops, pubs and café in Chew Magna. Pub in Stanton Drew. DIRECTIONS AND INFORMATION START/END Free car park in the Turn left out of the car park then turn right by the co-op. Take the centre of Chew Magna first right and walk along Silver Street. Grid ref: ST576631 (1) At a T-junction turn left and follow the road uphill, stay on the HOW TO road as it bends to the right passing a footpath sign on the left. GET THERE (2) At the next right bend take a signed footpath on the left, going up some steps to a metal kissing gate, then go uphill across a BY BIKE field to another metal kissing gate. -

Pigeonhouse Stream and the Malago (2010)

Wildlife Survey of PIGEONHOUSE STREAM AND THE MALAGO May / August 2010 For South Bristol Riverscapes Partnership Phil Quinn (Ecology and land use) MIEEM Flat 4, 15 Osborne Road, Clifton, Bristol, BS8 2HB. Tel. 0117 9747012; mob. 0796 2062917; email: [email protected] Wildlife Survey of Pigeonhouse Stream and the Malago (2010) CONTENTS Page 1. Summary 3-4 2. Remit 5 3. Site description 5-6 4. Methodology 7-8 5. Caveat 8 6. Results 8-40 6.1 The Malago 8-25 6.1.1 Dundry Slopes 9-13 M1 East of Strawberry Lane 9 M2 West of Strawberry Lane 10 M3 Ditch in a hedge 10 M4: A Malago is Born 10-11 M5: Teenage Malago 11-12 M6: Pretender to the Throne 12 M7: Claypiece Road isolate 12 6.1.2 Hengrove Plain and Bedminster 14-25 M8: The Stream Invisible 14 M9: Suburban Streamside 14-15 M10: Malago Valley SNCI 15-16 M10a Small tributary ditch 17 M11: A Whimper of a Watercourse 17-18 M12: Up the Junction 18 M13: Fire, Fire, Pour on Water 18-19 M14: Malago Incognito 20 M15: Parson Street to Marksbury Road 20-21 M16: Malago Vale 21-22 M17: The Bedminster Triangle 22-23 M18: Cotswold Road Canyon 23-24 M19: Water Rail 24 M20: Clarke Street dog-leg 24-25 1 Wildlife Survey of Pigeonhouse Stream and the Malago (2010) 6.2 Pigeonhouse Stream 25-40 6.2.1 Dundry Slopes 26-33 P1: Lower slopes tributary stream 26-27 P2a: Pigeonhouse Stream (headwaters) 27 P2b: Pigeonhouse Stream (tufa stream) 28 P2c: Pigeonhouse Stream (ancient woodland) 28-29 P2d: Pigeonhouse Stream (middle slopes) 29 P2e: Pigeonhouse Stream (south of pipeline crossing) 30 P2f: Pigeonhouse Stream (pipeline crossing) 30 P2g: Pigeonhouse Stream (pipeline crossing to culvert) 31 P3: Main tributary 32 P3a: Minor stream 32 P4: Upper tributary stream 33 6.2.2 Hengrove Plain 34-40 P5: Resurgence 34 P6: Hareclive Road to Fulford Road 34-35 P7: Whitchurch Lane or Bust 35-36 P8: The Hengrove Lake District 37 P9: Crox Bottom 37-38 P10: Hartcliffe Way / Pigeonhouse Stream 39-40 7. -

Stowey Sutton Parish Character Assessment

Stowey Sutton Parish Council Placemaking Plan Parish Character Assessment November 2013 Stowey Sutton Parish Council i Stowey Sutton Parish Council Contents Table of Figures ......................................................................................................................... iv Table of Maps........................................................................................................................... vii Introduction ............................................................................................................................... 1 Community volunteers .............................................................................................................. 1 Summary .................................................................................................................................... 3 Woodcroft Estate ....................................................................................................................... 5 Church Lane ............................................................................................................................. 13 Sutton Hill Rd & Top Sutton ..................................................................................................... 19 Bonhill Lane & Bonhill Road ..................................................................................................... 27 Cappards Estate ....................................................................................................................... 33 Ham Lane & Stitchings -

Bristol, Avon Valleys and Ridges (NCA 118)

NELMS target statement for Bristol, Avon Valleys and Ridges (NCA 118) Your application is scored and a decision made on the points awarded. Both top priorities and lower priorities score points but you should select at least one top priority. Scoring is carried out by... Choosing priorities To apply you should choose at least one of the top priorities, and you can choose lower priorities - this may help with your application. Top priorities Priority group Priority type Biodiversity Priority habitats Priority species Water Water quality Flood and coastal risk management Historic environment Designated historic and archaeological features Undesignated historic and archaeological features of high significance Woodland priorities Woodland management Woodland planting Landscape Climate Change Multiple environmental benefits Lower priorities Priority group Priority type Lower priorities Water quality Archaeological and historic features Woodland Biodiversity - top priorities Priority habitats You should carry out land management practices and capital works that maintains, restores and creates priority habitats. Maintain priority habitat such as: • Coastal and floodplain grazing marsh • Lowland meadows • Lowland calcareous grassland Reedbeds Traditional orchard • Lowland dry acid grassland Wood Pasture and Parkland Restore priority habitats (especially proposals which make existing sites bigger or help join up habitat networks) such as: ● Coastal and floodplain grazing marsh • Lowland meadows • Lowland calcareous grassland Reedbeds Traditional -

Bus Timetables

Bus Timetables To Bristol, 672 service, Monday to Saturday Time leaving Bishop Sutton, Post Office 0720 0957 Time arriving at Bristol, Union Street 0826 1059 From Bristol, 672 service, Monday to Saturday Time leaving Bristol, Union Street 1405 1715 Time arriving at Bishop Sutton 1510 1824 To & From Tesco & Midsomer Norton, 754 service, Mondays only Time leaving Bishop Sutton 0915 Time leaving Midsomer Norton 1236 Time arriving at & leaving Tesco 1024 Time arriving at & leaving at Tesco 1244 Time arriving at Midsomer Norton 1030 Time arriving at Bishop Sutton 1350 To & From Weston-Super-Mare & Wells*, 134 service, Tuesdays only Time leaving Bishop Sutton, Time leaving Weston-s-Mare, 0933 1300 opposite Post Office Regent Street Time Arriving at Weston-s-Mare 1039 Time Arriving at Bishop Sutton 1359 *Change at Blagdon for Wells on the 683 service, which leaves Wells at 1310 & reaches Blagdon at 1345 to change back to the 134 service to Bishop Sutton. Through fares are available. To & From Bath, 7521 service, Wednesdays only Time leaving Bishop Sutton, Woodcroft 0924 Time leaving Bath, Grand Parade 1345 Time arriving at Bath, Grand Parade 1015 Time arriving at Bishop Sutton 1431 To & From Congresbury & Nailsea, 128 service, Thursdays only Time leaving Bishop Sutton, Opp PO 0909 Time leaving Nailsea, Link Road 1210 Time arriving at & leaving Congresbury 0944 Time arriving at & leaving Congresbury 1245 Time arriving at Nailsea 1015 Time arriving at Bishop Sutton 1319 To & From Keynsham, 640 service, Fridays only Time leaving Bishop Sutton, Post Office 0920 Time leaving Keynsham, Ashton Way 1240 Time arriving at Keynsham, Ashton Way 1015 Time arriving at Bishop Sutton 1333 All buses pickup & drop-off from the bus stop outside the village shop / post office, except for the 7521 which is timetabled to pick up from the Woodcroft stop, which is roughly 100 metres after The Old Pit garage and on that side of the road, at the end of the village, however they often stop outside the shop as well. -

5 Chew Valley Circular

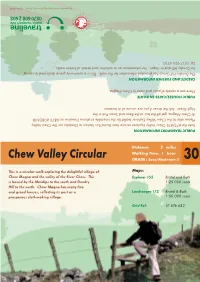

WalkA4•16-30 2/15/05 2:21 PM Page 15 Designed by Visual Technology. Bristol City Council. 0205/490 BR 0205/490 Council. City Bristol Technology. Visual by Designed Tel. 0117 935 9710. 935 0117 Tel. for Dundry Hill and its slopes. For information on its activities and details of further walks further of details and activities its on information For slopes. its and Hill Dundry for The Dundry Hill Group has provided information for this walk. This is a community group dedicated to caring caring to dedicated group community a is This walk. this for information provided has Group Hill Dundry The CREDITS AND FURTHER INFORMATION FURTHER AND CREDITS There are a variety of pubs and cafes in Chew Magna. Chew in cafes and pubs of variety a are There PUBLIC HOUSES/CAFES EN ROUTE EN HOUSES/CAFES PUBLIC High Street. Ask the driver if you are unsure of its location. location. its of unsure are you if driver the Ask Street. High At Chew Magna, get off the bus at the Bear and Swan Pub in the the in Pub Swan and Bear the at bus the off get Magna, Chew At Please refer to the Chew Valley Explorer leaflet for the timetable or phone Traveline on 0870 6082608. 0870 on Traveline phone or timetable the for leaflet Explorer Valley Chew the to refer Please Take the 672/674 Chew Valley Explorer service from Bristol Bus Station to Cheddar via The Chew Valley. Chew The via Cheddar to Station Bus Bristol from service Explorer Valley Chew 672/674 the Take PUBLIC TRANSPORT INFORMATION TRANSPORT PUBLIC Distance: 2 miles Walking Time: 1 hour 30 Chew Valley Circular GRADE : Easy/Moderate 3 This is a circular walk exploring the delightful village of Maps: Chew Magna and the valley of the River Chew. -

Pensford September Mag 09

Industrial, Commercial and September 09 Domestic Scaffolding ● Quality Scaffolding ● Competitive Rates ● Safety Our Priority ● Very Reliable Service ● 7 Days / 24 Hours ● 20 Years Experience ● C.I.T.B Qualified Team of Erectors Bristol: 01179 649 000 Bath: 01225 334 222 Mendip: 01761 490 505 Head Office: Unit 3, Bakers Park, Cater Rd. Bristol. BS13 7TT United Benefice of Publow with Pensford, Compton Dando and Chelwood 20p UNITED BENEFICE OF PUBLOW WITH PENSFORD, COMPTON DANDO AND CHELWOOD Directory of Local Organisations Bath & North East Somerset Chelwood Mr R. Nicholl 01275 332122 Council ComptonDando Miss S. Davis 472356 Publow Mr P. Edwards 01275 892128 Assistant Priest: Revd Sue Stevens 490898 Bristol Airport (Noise Concerns) 01275 473799 Woollard Place, Woollard Chelwood Parish Council Chairman Mr P. Sherborne 490586 Chelwood Bridge Rotary Club Tony Quinn 490080 Compton Dando Parish Chairman Ms T. Mitchell 01179 860791 Reader: Mrs Noreen Busby 452939 Council Clerk Mrs D. Drury 01179 860552 Compton Dando CA Nan Young 490660 Churchwardens: Publow Parish Council Chairman Mr A.J Heaford 490271 Publow with Pensford: Miss Janet Ogilvie 490020 Clerk Mrs J. Bragg 01275 333549 Pensford School Headteacher Ms L. MAcIsaac 490470 Mrs Janet Smith 490584 Chair of Governors Mr B. Watson 490506 Compton Dando: Mr Clive Howarth 490644 Chelwood Village Hall Bookings Mr Pat Harrison 490218 Jenny Davis 490727 Compton Dando Parish Hall Bookings Mrs Fox 490955 Chelwood: Mrs Marge Godfrey 490949 Pensford Memorial Hall Chairman Terry Phillips 490426 Bookings