Decision-Making in the Immediate Aftermath of 9/11

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ex Post Facto

EX POST FACTO JOURNAL OF THE HISTORY STUDENTS SPRING AT SAN FRANCISCO STATE UNIVERSITY 2020 EX POST FACTO Journal of the History Students at San Francisco State University Volume XXIV 2020 Ex Post Facto is published annually by the students of the Department of History at San Francisco State University and members of the Kappa Phi Chapter of Phi Alpha Theta, the national History honors society. All views of fact or opinion are the sole responsibility of the authors and may not re- flect the views of the editorial staff. Questions or comments may be directed to Ex Post Facto, Department of History, San Francisco State University, 1600 Holloway Avenue, San Fran- cisco, CA 94132. Contact us via email at [email protected]. The Journal is pub- lished online at http:/history.sfsu.edu/content/ex-post- facto-history-journal. The Ex Post Facto editorial board gratefully acknowledges the funding pro- vided by the Instructionally Related Activities Committee at San Francisco State University. The board also wishes to thank Dr. Eva Sheppard Wolf for her continued confidence and support, as well as all of the Department of History’s professors who have both trained and encouraged students in their pursuit of the historian’s craft. These professors have empowered their students to write the inspiring scholarship included in this publication. In addition to support from within our own department, we have also been fortunate to receive outstanding contributions from the SFSU School of De- sign. Therein we are particularly grateful for the assistance of Dr. Joshua Singer and Aitalina Indeeva. -

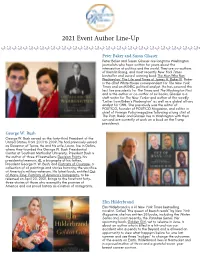

2021 Event Author Line-Up

2021 Event Author Line-Up Peter Baker and Susan Glasser Peter Baker and Susan Glasser are longtime Washington journalists who have written for years about the intersection of politics and the world. They are co-authors of Kremlin Rising, and most recently New York Times bestseller and award-winning book The Man Who Ran Washington: The Life and Times of James A. Baker III. Baker is the chief White House correspondent for The New York Times and an MSNBC political analyst. He has covered the last five presidents for The Times and The Washington Post and is the author or co-author of six books. Glasser is a staff writer for The New Yorker and author of the weekly “Letter from Biden’s Washington” as well as a global affairs analyst for CNN. She previously was the editor of POLITICO, founder of POLITICO Magazine, and editor-in- chief of Foreign Policy magazine following a long stint at The Post. Baker and Glasser live in Washington with their son and are currently at work on a book on the Trump presidency. George W. Bush George W. Bush served as the forty-third President of the United States, from 2001 to 2009. He had previously served as Governor of Texas. He and his wife, Laura, live in Dallas, where they founded the George W. Bush Presidential Center at Southern Methodist University. President Bush is the author of three #1 bestsellers: Decision Points, his presidential memoir; 41, a biography of his father, President George H. W. Bush; and Portraits of Courage, a collection of oil paintings and stories honoring the sacrifice of America’s military veterans. -

Proquest Dissertations

NOTE TO USERS This reproduction is the best copy available. ® UMI u Ottawa I,'I nivrrsilc canadirrmi' (.'iiiiiiilij's university nm FACULTE DES ETUDES SUPERIEURES FACULTY OF GRADUATE AND ET POSTOCTORALES U Ottawa POSDOCTORAL STUDIES [,'University eanadienne Canada's university Vajmeh Tabibi AUTEUR DE LA THESE / AUTHOR OF THESIS M.A. (Criminology) GRADE/DEGREE Department of Criminology FACULTE, ECOLE, DEPARTEMENT / FACULTY, SCHOOL, DEPARTMENT Experiences and Perceptions of Afghan-Canadian men in the Post-September 11th Context TITRE DE LA THESE / TITLE OF THESIS Christine Bruckert ___„„„„„___„_ _.„.____„_____^ EXAMINATEURS (EXAMINATRICES) DE LA THESE/THESIS EXAMINERS Kathryn Campbell Bastien Quirion .Gar.Y_ W. Slater Le Doyen de la Faculte des etudes superieures et postdoctorales / Dean of the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies Experiences and Perceptions of Afghan-Canadian men in the Post-September 11th Context Vajmeh Tabibi Thesis submitted to the faculty of Graduate and Postgraduate Studies In partial Fulfillment of the requirement for the MA Degree in Criminology Department of Criminology Faculty of Social Sciences University of Ottawa Vajmeh Tabibi, Ottawa, 2008 Library and Bibliotheque et 1*1 Archives Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-46500-4 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-46500-4 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur -

Lipstick on the Pig Lipstick on The

ELECTION 2008 Lipstick on the Pig Robert David STEELE Vivas Public Intelligence Minuteman Prefaces from Senator Bernie Sanders (I‐VT), Tom Atlee, Thom Hartmann, & Sterling Seagraves Take a Good Look Our Political System Today Let’s Lose the Lipstick, Eat the Pig, and Move On! ELECTION 2008 Lipstick on the Pig Robert David STEELE Vivas Co‐Founder, Earth Intelligence Network Copyright © 2008, Earth Intelligence Network (EIN) This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial 3.0 Unported License For details go to http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/us/ EIN retains commercial and revenue rights. Authors retain other rights offered under copyright. Entire book and individual chapters free online at www.oss.net/PIG. WHAT THIS REALLY MEANS: 1. You can copy, print, share, and translate this work as long as you don’t make money on it. 2. If you want to make money on it, by all means, 20% to our non-profit and we are happy. 3. What really matters is to get this into the hands of as many citizens as possible. 4. Our web site in Sweden is robust, but you do us all a favor if you host a copy for your circle. Books available by the box of 20 at 50% off retail ($35.00). $20 is possible at any printer if you negotiate, we have to pay $35 with our retail discount, but actual cost to printer is $10. Published by Earth Intelligence Network October 2008 Post Office Box 369, Oakton, Virginia 22124 www.earth-intelligence.net Cover graphic is a composition created by Robert Steele using open art available on the Internet. -

George W Bush Childhood Home Reconnaissance Survey.Pdf

Intermountain Region National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior August 2015 GEORGE W. BUSH CHILDHOOD HOME Reconnaissance Survey Midland, Texas Front cover: President George W. Bush and First Lady Laura Bush speak to the media after touring the President’s childhood home at 1421 West Ohio Avenue, Midland, Texas, on October 4, 2008. President Bush traveled to attend a Republican fundraiser in the town where he grew up. Photo: SAUL LOEB/AFP/Getty Images CONTENTS BACKGROUND AND PURPOSE — i SUMMARY OF FINDINGS — iii RECONNAISSANCE SURVEY PROCESS — v NPS CRITERIA FOR EVALUATION OF NATIONAL SIGNIFICANCE — vii National Historic Landmark Criterion 2 – viii NPS Theme Studies on Presidential Sites – ix GEORGE W. BUSH: A CHILDHOOD IN MIDLAND — 1 SUITABILITY — 17 Childhood Homes of George W. Bush – 18 Adult Homes of George W. Bush – 24 Preliminary Determination of Suitability – 27 HISTORY AND DESCRIPTION OF THE GEORGE W. BUSH CHILDHOOD HOME, MIDLAND TEXAS — 29 Architectural Description – 29 Building History – 33 FEASABILITY AND NEED FOR NPS MANAGEMENT — 35 Preliminary Determination of Feasability – 37 Preliminary Determination of Need for NPS Management – 37 CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS — 39 APPENDIX: THE 41ST AND 43RD PRESIDENTS AND FIRST LADIES OF THE UNITED STATES — 43 George H.W. Bush – 43 Barbara Pierce Bush – 44 George W. Bush – 45 Laura Welch Bush – 47 BIBLIOGRAPHY — 49 SURVEY TEAM MEMBERS — 51 George W. Bush Childhood Home Reconnaissance Survey George W. Bush’s childhood bedroom at the George W. Bush Childhood Home museum at 1421 West Ohio Avenue, Midland, Texas, 2012. The knotty-pine-paneled bedroom has been restored to appear as it did during the time that the Bush family lived in the home, from 1951 to 1955. -

Shia-Sunni Sectarianism: Iran’S Role in the Tribal Regions of Pakistan

SHIA-SUNNI SECTARIANISM: IRAN’S ROLE IN THE TRIBAL REGIONS OF PAKISTAN A Thesis submitted to the Faculty of The School of Continuing Studies and of The Graduate School of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Liberal Studies By Shazia Kamal Farook, B.A. Georgetown University Washington, D.C. April 1, 2015 Copyright © Shazia Kamal Farook 2015 All Rights Reserved ii ABSTRACT SHIA-SUNNI SECTARIANISM: IRAN’S ROLE IN THE TRIBAL REGIONS OF PAKISTAN SHAZIA KAMAL FAROOK, B.A. MALS Mentor: Dr. John Esposito This thesis analyzes Shia-Sunni sectarianism in the northern tribal areas of Pakistan, and the role of Iran in exacerbating such violence in recent years. The northern tribal regions have been experiencing an unprecedented level of violence between Sunnis and Shias since the rise of the Tehreek-e-Taliban militant party in the area. Most research and analysis of sectarian violence has marked the rise as an exacerbation of theologically- driven hatred between Sunnis and Shias. Moreover, recent scholarship designates Pakistan as a self- deprecating “failed” state because of its mismanagement and bad governance with regard to the “war on terror.” However, the literature ignores the role of external factors, such as Iranian’s foreign policy towards Pakistan playing out in the tribal areas of Pakistan in the period since the Soviet-Afghan War. Some of the greatest threats to the Shia population in Pakistan arise from the Islamization policies of General Zia-ul-Haq in the 1980s. Policies in favor of Sunni Islam have since pervaded the nation and have created hostile zones all over the nation. -

"Our Grief and Anger": George W. Bush's Rhetoric in the Aftermath of 9

ISSN: 2392-3113 Rhetoric of crisis Retoryka kryzysu 7 (1) 2020 EDITORS: AGNIESZKA KAMPKA, MARTA RZEPECKA RAFAŁ KUŚ JAGIELLONIAN UNIVERSITY https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2930-6447 [email protected] “Our Grief and Anger”: George W. Bush’s Rhetoric in the Aftermath of 9/11 as Presidential Crisis Communication „Nasz ból i gniew”: retoryka George’a W. Busha po zamachach z 11 września 2001 r. jako prezydencka komunikacja kryzysowa Abstract This paper offers a review and analysis of speeches delivered by President George W. Bush in the aftermath of the terrorist attacks of September 11th, 2001. Bush’s motivations, goals, and persuasive strategies are discussed in detail in the following study, with consideration for the cultural and political contexts of American oratory and the idiosyncratic features of the Republican as a public speaker. The characteristics of Bush's 9/11 communication acts are then compared with Franklin D. Roosevelt's Pearl Harbor speech in order to analyze the differences between the two politicians' rhetorical modi operandi as well as the changing political environment of the U.S. Artykuł obejmuje przegląd i analizę przemówień wygłoszonych przez Prezydenta George’a W. Busha w okresie po zamachach terrorystycznych z 11 września 2001 r. Motywy, cele i strategie perswazyjne Busha zostały w nim szczegółowo omówione, z uwzględnieniem kulturowych i politycznych kontekstów krasomówstwa amerykańskiego oraz wyróżniających cech republikanina jako mówcy publicznego. Charakterystyka aktów komunikacyjnych Busha z 9/11 została następnie porównana z przemówieniem Franklina D. Roosevelta w sprawie ataku na Pearl Harbor w celu przeanalizowania różnic pomiędzy retorycznymi modi operandi obydwu polityków, jak również zmian zachodzących w środowisku politycznym USA. -

GEORGE W. BUSH Recent Titles in Greenwood Biographies Halle Berry: a Biography Melissa Ewey Johnson Osama Bin Laden: a Biography Thomas R

GEORGE W. BUSH Recent Titles in Greenwood Biographies Halle Berry: A Biography Melissa Ewey Johnson Osama bin Laden: A Biography Thomas R. Mockaitis Tyra Banks: A Biography Carole Jacobs Jean-Michel Basquiat: A Biography Eric Fretz Howard Stern: A Biography Rich Mintzer Tiger Woods: A Biography, Second Edition Lawrence J. Londino Justin Timberlake: A Biography Kimberly Dillon Summers Walt Disney: A Biography Louise Krasniewicz Chief Joseph: A Biography Vanessa Gunther John Lennon: A Biography Jacqueline Edmondson Carrie Underwood: A Biography Vernell Hackett Christina Aguilera: A Biography Mary Anne Donovan Paul Newman: A Biography Marian Edelman Borden GEORGE W. BUSH A Biography Clarke Rountree GREENWOOD BIOGRAPHIES Copyright 2011 by ABC-CLIO, LLC All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, except for the inclusion of brief quotations in a review, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Rountree, Clarke, 1958– George W. Bush : a biography / Clarke Rountree. p. cm. — (Greenwood biographies) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-313-38500-1 (hard copy : alk. paper) — ISBN 978-0-313-38501-8 (ebook) 1. Bush, George W. (George Walker), 1946– 2. United States— Politics and government—2001–2009. 3. Presidents—United States— Biography. I. Title. E903.R68 2010 973.931092—dc22 [B] 2010032025 ISBN: 978-0-313-38500-1 EISBN: 978-0-313-38501-8 15 14 13 12 11 1 2 3 4 5 This book is also available on the World Wide Web as an eBook. -

Why Did Bush Bypass the Un in 2003? Unilateralism, Multilateralism and Presidential Leadership

White House Studies (2011) ISSN: 1535-4738 Volume 11, Number 3, pp. © 2012 Nova Science Publishers, Inc. WHY DID BUSH BYPASS THE UN IN 2003? UNILATERALISM, MULTILATERALISM AND PRESIDENTIAL LEADERSHIP Alexander Thompson Department of Political Science Ohio State University, USA ABSTRACT Why did President George W. Bush bypass the UN and adopt a largely unilateral approach when he invaded Iraq in 2003? Given the political and material benefits of multilateralism, this is a puzzling case on both theoretical and cost-benefit grounds, especially because Iraq did not pose an urgent national security threat to the United States. Three overlapping factors help to explain this outcome: the influence of the September 11, 2001, attacks; the predispositions of Bush’s key advisers; and the dysfunctional decision-making process prior to the war, which served to enhance the perceived costs of multilateralism and the perceived benefits of unilateral action. With the lessons of Iraq in mind, U.S. presidents should use constructive leadership at the UN to capture the long-term benefits of working through multilateral institutions. INTRODUCTION In security affairs, as in other realms of foreign policy, states sometimes choose to operate multilaterally and other times work alone. The choice between unilateralism and multilateralism has always occupied foreign policy leaders but has become especially salient since the Second World War, with the rise of international security organizations and the growth of international law governing the use of force. There are simply more options in the modern era for pursuing policies more or less multilaterally, and multilateralism has indeed taken hold as never before. -

4 the 9 11 Commission Report David Ray Griffin.Pdf

The 9 11 Commission Report Omissions And Distortions By: David Ray Griffin ISBN: 1566565847 See detail of this book on Amazon.com Book served by AMAZON NOIR (www.amazon-noir.com) project by: PAOLO CIRIO paolocirio.net UBERMORGEN.COM ubermorgen.com ALESSANDRO LUDOVICO neural.it Page 1 Page 2 Page 3 Page 4 Page 5 Page 6 Page 7 Page 8 Page 9 Page 10 Page 11 Page 12 Page 13 Page 14 Page 15 Page 16 Page 17 Page 18 Page 19 CHAPTER ONE The Alleged Hijackers As I explained in the Introduction, the 9/11 Commission for the A most part simply omits evidence that would cast doubt on the official account of 9/11. When it does refer to evidence of this type, it typically mentions only part of it accurately, omitting or distorting the remainder. The present chapter illustrates this criticism in relation to the Commission's response to problems that have emerged with respect to the alleged hijackers. Six ALLEGED HIJACKERS STILL ALIVE One problem is that at least six of the nineteen men officially identified as the suicide hijackers reportedly showed up alive after 9/11. For example, Waleed al-Shehri-said to have been on American Airlines Flight 11, which hit the North Tower of the World Trade Center-was interviewed after 9/11 by a London-based newspaper.' He also, the Associated Press reported, spoke on September 22 to the US embassy in Morocco, explaining that he lives in Casablanca, working as a pilot for Royal Air Maroc. Likewise, Ahmed al-Nami and Saeed al-Ghamdi-both said to have been on United Airlines Flight 93, which crashed in Pennsylvania-were shocked, they told Telegraph reporter David Harrison, to hear that they had died in this crash. -

Learning in a Double Loop: the Strategic Transformation of Al-Qaeda by Michael Fürstenberg and Carolin Görzig

PERSPECTIVES ON TERRORISM Volume 14, Issue 1 Research Notes Learning in a Double Loop: The Strategic Transformation of Al-Qaeda by Michael Fürstenberg and Carolin Görzig Abstract Like any type of organization, terrorist groups learn from their own experiences as well as those of others. These processes of organizational learning have, however, been poorly understood so far, especially regarding deep strategic changes. In this Research Note, we apply a concept developed to understand learning of business organizations to recent transformations of jihadist groups. The question we want to shed light on using this approach is whether, and in which ways, terrorist groups are able to question not only their immediate modus operandi, but also the fundamental assumptions their struggle is built on. More specifically, we focus the inquiry on the development of the Al-Qaeda network. Despite its acknowledged penchant for learning, the ability of the jihadists to transform on a deeper level has often been denied. We seek to reassess these claims from the perspective of a double-loop learning approach by tracing the strategic evolution of Al-Qaeda and its eventual breakaway faction, Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham (HTS). Keywords: Organizational learning, terrorist transformation, strategic change, jihadism, Al-Qaeda, Hayat Tahrir al-Sham Introduction Departing from earlier assertions that terrorist organizations are generally conservative and averse to experimentation and change,[1] there is a growing literature dealing with the capacity of militant actors for flexibility, learning and innovative behavior.[2] However, a large part of this research focuses narrowly on tactical advances, or what Singh has termed “bomb and bullet” innovations.[3] We argue that it is equally, if not even more, important to study learning processes that are directed at more profound transformations of the fundamental approaches of groups. -

Annotated Bibliography

ELECTION 2008: Lipstick on the Pig, Annotated Bibliography Annotated Bibliography1 Anti‐Americanism, Blowback, Why the Rest Hates the West .......................................................... 92 Betrayal of the Public Trust .............................................................................................................. 93 Biomimicry, Green Chemistry, Ecological Economics, Natural Capitalism ....................................... 98 Blessed Unrest, Dignity, Dissent, & the Tao of Democracy .............................................................. 99 Capitalism, Globalization, Peak Oil, & “Free” Trade Run Amok ..................................................... 100 Collective Intelligence, Power of Us, We Are One, & Wealth of We .............................................. 102 Culture of Catastrophe, Cheating, Conflict, & Conspiracy .............................................................. 104 Deception, Facts, Fog, History (Lost), Knowledge, Learning, & Lies ............................................... 104 Democracy in Decline ..................................................................................................................... 107 Emerging and Evolving Threats & Challenges ................................................................................ 110 Failed States, Poverty, Wrongful Leadership, and the Sorrows of Empire .................................... 114 Future of Life, State of the Future, Plan B 3.0 ...............................................................................