I. Loot* Read 24 November 2017

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mountstuart Elphinstone: an Anthropologist Before Anthropology

Mountstuart Elphinstone Mountstuart Elphinstone in South Asia: Pioneer of British Colonial Rule Shah Mahmoud Hanifi Print publication date: 2019 Print ISBN-13: 9780190914400 Published to Oxford Scholarship Online: September 2019 DOI: 10.1093/oso/9780190914400.001.0001 Mountstuart Elphinstone An Anthropologist Before Anthropology M. Jamil Hanifi DOI:10.1093/oso/9780190914400.003.0003 Abstract and Keywords During 1809, Mountstuart Elphinstone and his team of researchers visited the Persianate "Kingdom of Caubul" in Peshawar in order to sign a defense treaty with the ruler of the kingdom, Shah Shuja, and to collect information for use by the British colonial government of India. During his four-month stay in Peshawar, and subsequent two years research in Poona, India, Elphinstone collected a vast amount of ethnographic information from his Persian-speaking informants, as well as historical texts about the ethnology of Afghanistan. Some of this information provided the material for his 1815 (1819, 1839, 1842) encyclopaedic "An Account of the Kingdom of Caubul" (AKC), which became the ethnographic bible for Euro-American writings about Afghanistan. Elphinstone's competence in Farsi, his subscription to the ideology of Scottish Enlightenment, the collaborative methodology of his ethnographic research, and the integrity of the ethnographic texts in his AKC, qualify him as a pioneer anthropologist—a century prior to the birth of the discipline of anthropology in Europe. Virtually all Euro-American academic and political writings about Afghanistan during the last two-hundred years are informed and influenced by Elphinstone's AKC. This essay engages several aspects of the ethnological legacy of AKC. Keywords: Afghanistan, Collaborative Research, Ethnography, Ethnology, National Character For centuries the space marked ‘Afghanistan’ in academic, political, and popular discourse existed as a buffer between and in the periphery of the Persian and Persianate Moghol empires. -

Sources of Maratha History: Indian Sources

1 SOURCES OF MARATHA HISTORY: INDIAN SOURCES Unit Structure : 1.0 Objectives 1.1 Introduction 1.2 Maratha Sources 1.3 Sanskrit Sources 1.4 Hindi Sources 1.5 Persian Sources 1.6 Summary 1.7 Additional Readings 1.8 Questions 1.0 OBJECTIVES After the completion of study of this unit the student will be able to:- 1. Understand the Marathi sources of the history of Marathas. 2. Explain the matter written in all Bakhars ranging from Sabhasad Bakhar to Tanjore Bakhar. 3. Know Shakavalies as a source of Maratha history. 4. Comprehend official files and diaries as source of Maratha history. 5. Understand the Sanskrit sources of the Maratha history. 6. Explain the Hindi sources of Maratha history. 7. Know the Persian sources of Maratha history. 1.1 INTRODUCTION The history of Marathas can be best studied with the help of first hand source material like Bakhars, State papers, court Histories, Chronicles and accounts of contemporary travelers, who came to India and made observations of Maharashtra during the period of Marathas. The Maratha scholars and historians had worked hard to construct the history of the land and people of Maharashtra. Among such scholars people like Kashinath Sane, Rajwade, Khare and Parasnis were well known luminaries in this field of history writing of Maratha. Kashinath Sane published a mass of original material like Bakhars, Sanads, letters and other state papers in his journal Kavyetihas Samgraha for more eleven years during the nineteenth century. There is much more them contribution of the Bharat Itihas Sanshodhan Mandal, Pune to this regard. -

Reg. No Name in Full Residential Address Gender Contact No

Reg. No Name in Full Residential Address Gender Contact No. Email id Remarks 20001 MUDKONDWAR SHRUTIKA HOSPITAL, TAHSIL Male 9420020369 [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 PRASHANT NAMDEORAO OFFICE ROAD, AT/P/TAL- GEORAI, 431127 BEED Maharashtra 20002 RADHIKA BABURAJ FLAT NO.10-E, ABAD MAINE Female 9886745848 / [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 PLAZA OPP.CMFRI, MARINE 8281300696 DRIVE, KOCHI, KERALA 682018 Kerela 20003 KULKARNI VAISHALI HARISH CHANDRA RESEARCH Female 0532 2274022 / [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 MADHUKAR INSTITUTE, CHHATNAG ROAD, 8874709114 JHUSI, ALLAHABAD 211019 ALLAHABAD Uttar Pradesh 20004 BICHU VAISHALI 6, KOLABA HOUSE, BPT OFFICENT Female 022 22182011 / NOT RENEW SHRIRANG QUARTERS, DUMYANE RD., 9819791683 COLABA 400005 MUMBAI Maharashtra 20005 DOSHI DOLLY MAHENDRA 7-A, PUTLIBAI BHAVAN, ZAVER Female 9892399719 [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 ROAD, MULUND (W) 400080 MUMBAI Maharashtra 20006 PRABHU SAYALI GAJANAN F1,CHINTAMANI PLAZA, KUDAL Female 02362 223223 / [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 OPP POLICE STATION,MAIN ROAD 9422434365 KUDAL 416520 SINDHUDURG Maharashtra 20007 RUKADIKAR WAHEEDA 385/B, ALISHAN BUILDING, Female 9890346988 DR.NAUSHAD.INAMDAR@GMA RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 BABASAHEB MHAISAL VES, PANCHIL NAGAR, IL.COM MEHDHE PLOT- 13, MIRAJ 416410 SANGLI Maharashtra 20008 GHORPADE TEJAL A-7 / A-8, SHIVSHAKTI APT., Male 02312650525 / NOT RENEW CHANDRAHAS GIANT HOUSE, SARLAKSHAN 9226377667 PARK KOLHAPUR Maharashtra 20009 JAIN MAMTA -

Assessment of Agro-Tourism Potential in Junnar Tehsil, Maharashtra, India

Scholarly Research Journal for Interdisciplinary Studies, Online ISSN 2278-8808, SJIF 2016 = 6.17, www.srjis.com UGC Approved Sr. No.45269, SEPT-OCT 2017, VOL- 4/36 ASSESSMENT OF AGRO-TOURISM POTENTIAL IN JUNNAR TEHSIL, MAHARASHTRA, INDIA Thorat S. D.1 & Suryawanshi R.S.2 1PhD Research Student, Savitribai Phule Pune University, Pune-411007. E-mail - [email protected] 2Professor, Department of Geography, Abasaheb Garware College, Pune-411004, S.P.P.U. E-mail –[email protected] The present research paper is an attempt to analyse the level of development and potential of Agro- tourism in Junnar Tehsil in Pune District Maharashtra. Agro-tourism is the emerging branch of tourism in India. It helped for sustainable development in rural area. Agro-tourism give the opportunity to tourist to get aware with agricultural area, agricultural operations, local food and tradition of local area and support to economic development of farmers. The Junnar Tehsil in Pune district have many tourist destinations, but yet this Tehsil is not highlighted to large scale Agro- tourism practices. It is mainly because of lack of facilities and low development of area. The present research paper focuses on find out the potential area for agro-tourism in Junnar Tehsil. The development status of agro-tourism potential composite index is product of physiographic index and cropping pattern based on a GIS techniques. Keywords: Agro-Tourism, Composite Index and GIS technique. Scholarly Research Journal's is licensed Based on a work at www.srjis.com Introduction Tourism plays very important role in economic development on regional level. Now day’s tourism is one of the fastest growing industries in the world. -

FALL of MARATHAS, 1798–1818 A.D. the Position of Marathas in 1798 A.D

M.A. (HISTORY) PART–II PAPER–II : GROUP C, OPTION (i) HISTORY OF INDIA (1772–1818 A.D.) LESSON NO. 2.4 AUTHOR : PROF. HARI RAM GUPTA FALL OF MARATHAS, 1798–1818 A.D. The Position of Marathas in 1798 A.D. The Marathas had been split up into a loose confederacy. At the head of the Maratha empire was Raja of Sitara. His power had been seized by the Peshwa Baji Rao II was the Peshwa at this time. He became Peshwa at the young age of twenty one in December, 1776 A.D. He had the support of Nana Pharnvis who had secured approval of Bhonsle, Holkar and Sindhia. He was destined to be the last Peshwa. He loved power without possessing necessary courage to retain it. He was enamoured of authority, but was too lazy to exercise it. He enjoyed the company of low and mean companions who praised him to the skies. He was extremely cunning, vindictive and his sense of revenge. His fondness for wine and women knew no limits. Such is the character sketch drawn by his contemporary Elphinstone. Baji Rao I was a weak man and the real power was exercised by Nana Pharnvis, Prime Minister. Though Nana was a very capable ruler and statesman, yet about the close of his life he had lost that ability. Unfortunately, the Peshwa also did not give him full support. Daulat Rao Sindhia was anxious to occupy Nana's position. He lent a force under a French Commander to Poona in December, 1797 A.D. Nana Pharnvis was defeated and imprisoned in the fort of Ahmadnagar. -

Shivaji the Great

SHIVAJI THE GREAT BY BAL KRISHNA, M. A., PH. D., Fellow of the Royal Statistical Society. the Royal Economic Society. London, etc. Professor of Economics and Principal, Rajaram College, Kolhapur, India Part IV Shivaji, The Man and His .Work THE ARYA BOOK DEPOT, Kolhapur COPYRIGHT 1940 the Author Published by The Anther A Note on the Author Dr. Balkrisbna came of a Ksbatriya family of Multan, in the Punjab* Born in 1882, be spent bis boyhood in struggles against mediocrity. For after completing bis primary education he was first apprenticed to a jewel-threader and then to a tailor. It appeared as if he would settle down as a tailor when by a fortunate turn of events he found himself in a Middle Vernacular School. He gave the first sign of talents by standing first in the Vernacular Final ^Examination. Then he joined the Multan High School and passed en to the D. A. V. College, Lahore, from where he took his B. A* degree. Then be joined the Government College, Lahore, and passed bis M. A. with high distinction. During the last part of bis College career, be came under the influence of some great Indian political leaders, especially of Lala Lajpatrai, Sardar Ajitsingh and the Honourable Gopal Krishna Gokhale, and in 1908-9 took an active part in politics. But soon after he was drawn more powerfully to the Arya Samaj. His high place in the M. A. examination would have helped him to a promising career under the Government, but he chose differently. He joined Lala Munshiram ( later Swami Shraddha- Btnd ) *s a worker in the Guruk.ul, Kangri. -

The Keys to British Success in South Asia COLIN WATTERSON

The Keys to British Success in South Asia COLIN WATTERSON “God is on everyone’s side…and in the last analysis he is on the side with plenty of money and large armies” -Jean Anouilh For a period of a period of over one hundred years, the British directly controlled the subcontinent of India. How did a small island nation come on the Edge of the North Atlantic come to dominate a much larger landmass and population located almost 4000 miles away? Historian Sir John Robert Seeley wrote that the British Empire was acquired in “a fit of absence of mind” to show that the Empire was acquired gradually, piece-by-piece. This will paper will try to examine some of the most important reasons which allowed the British to successfully acquire and hold each “piece” of India. This paper will examine the conditions that were present in India before the British arrived—a crumbling central political power, fierce competition from European rivals, and Mughal neglect towards certain portions of Indian society—were important factors in British control. Economic superiority was an also important control used by the British—this paper will emphasize the way trade agreements made between the British and Indians worked to favor the British. Military force was also an important factor but this paper will show that overwhelming British force was not the reason the British military was successful—Britain’s powerful navy, ability to play Indian factions against one another, and its use of native soldiers were keys to military success. Political Agendas and Indian Historical Approaches The historiography of India has gone through four major phases—three of which have been driven by the prevailing world politics of the time. -

5. the Foundation of the Swaraj

5. The Foundation of the Swaraj In the first half of the seventeenth century, an epoch making personality emerged in Maharashtra - Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj. He established Swaraj by challenging the unjust ruling powers here. Shivaji Maharaj was born at the Shivneri fort near Junnar in Pune district on the day of Phalgun Vadya Tritiya in the Shaka year 1551, that is on 19 February 1630. Shahajiraje : Shahajiraje, the father of Shivaji Maharaj was a pre-eminent Sardar in the Deccan. The Mughals had launched a campaign to conquer the Nizamshahi Kingdom. The Adilshah of Bijapur allied with the Mughals in this campaign. Shahaji Maharaj did not wish the Mughals to get an entry into the South. So he tried to save Nizamshahi by offering stiff resistance to the Mughals. But he could not withstand the combined might of the Mughals Shahajiraje and the Adilshah. The Nizamshahi was defeated and came to an end in 1636 CE. After the Nizamshahi was wiped out, Shahajiraje became a Sardar of the Adilshah of Bijapur. The region comprising Pune, Supe, Indapur and Chakan parganas located between the Bheema and Neera rivers was vested in Shahajiraje as a jagir. This was continued by the Adilshah, and he also granted the jagir of Bengaluru and the neighbouring areas in Karnataka to Shahajiraje. For your information Jahagir or jagir means the right to enjoy the revenue of a region. The Sardars in the service of rulers used to get the revenue of the region as income instead of getting salaries directly. The region was chosen in such a way that the revenue would be equal to the salary. -

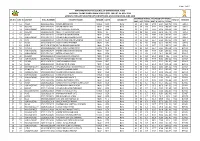

Merit Wise Selected Students List GEN-SC-ST-OBC.Xlsx

Page 1 of 10 MAHARASHTRA STATE COUNCIL OF EXAMINIATION, PUNE NATIONAL TALENT SEARCH EXAM 2018-19 (STD. 10th) DT. 04-NOV-2018 GENERAL CATEGORY SELECTED LIST FOR NATIONAL LEVEL EXAM ON 16-JUNE-2019 OBTAINED MARKS ROUNDED OFF MARKS SR.NO. DIST ID DISTRICT ROLL NUMBER STUDENT NAME GENDER CASTE DISABILITY RESULT REMARK MAT SAT TOTAL MAT % SAT % TOTAL 1 63 AKOLA E239196305162 RASIKA DINESH MAL Female GEN None 91 95 186 94.79 96.94 191.73 PASS GEN-1 2 33 JALGAON E239193303252 ARYAN RAJESH JAIN Male GEN None 89 94 183 92.71 95.92 188.63 PASS GEN-2 3 51 AURANGABAD E239195106107 AADITYA SANJAY KULKARNI Male GEN None 88 95 183 91.67 96.94 188.61 PASS GEN-3 4 33 JALGAON E239193302310 MEGH HITESHKUMAR GOHIL Male SC None 94 88 182 97.92 89.8 187.71 PASS GEN-4 5 52 JALNA E239195202402 ATHARVA RAMESH PAWAR Male GEN None 92 90 182 95.83 91.84 187.67 PASS GEN-5 6 51 AURANGABAD E239195115112 ATHARVA BALASAHEB CHIVATE Male GEN None 92 90 182 95.83 91.84 187.67 PASS GEN-6 7 21 PUNE E239192111421 SPRUHA PRABHANJAN SARNAIK Female GEN None 90 92 182 93.75 93.88 187.63 PASS GEN-7 8 52 JALNA M239195202244 YASH UDAYAN PARITKAR Male OBC None 93 89 182 96.88 89.9 186.77 PASS GEN-8 9 81 LATUR M239198102284 RUTVIK BABARUWAN MORE Male GEN None 91 91 182 94.79 91.92 186.71 PASS GEN-9 10 83 NANDED M239198302094 SAIRAJ KERBA SONMANKAR Female NT-B None 90 92 182 93.75 92.93 186.68 PASS GEN-10 11 51 AURANGABAD E239195106244 PARTH SUNILKUMAR SONGIRE Male OBC None 91 90 181 94.79 91.84 186.63 PASS GEN-11 12 51 AURANGABAD E239195110411 RITESH MOHAN PATIL Male GEN None 88 93 -

Expansion and Consolidation of Colonial Power Subject : History

Expansion and consolidation of colonial power Subject : History Lesson : Expansion and consolidation of colonial power Course Developers Expansion and consolidation of colonial power Prof. Lakshmi Subramaniam Professor, Centre for Studies in Social Sciences, Kolkata Dynamics of colonial expansion--1 and Dynamics of colonial expansion--2: expansion and consolidation of colonial rule in Bengal, Mysore, Western India, Sindh, Awadh and the Punjab Dr. Anirudh Deshpande Associate Professor, Department of History, University of Delhi Language Editor: Swapna Liddle Formating Editor: Ashutosh Kumar 1 Institute of lifelong learning, University of Delhi Expansion and consolidation of colonial power Table of contents Chapter 2: Expansion and consolidation of colonial power 2.1: Expansion and consolidation of colonial power 2.2.1: Dynamics of colonial expansion - I 2.2.2: Dynamics of colonial expansion – II: expansion and consolidation of colonial rule in Bengal, Mysore, Western India, Awadh and the Punjab Summary Exercises Glossary Further readings 2 Institute of lifelong learning, University of Delhi Expansion and consolidation of colonial power 2.1: Expansion and consolidation of colonial power Introduction The second half of the 18th century saw the formal induction of the English East India Company as a power in the Indian political system. The battle of Plassey (1757) followed by that of Buxar (1764) gave the Company access to the revenues of the subas of Bengal, Bihar and Orissa and a subsequent edge in the contest for paramountcy in Hindustan. Control over revenues resulted in a gradual shift in the orientation of the Company‟s agenda – from commerce to land revenue – with important consequences. This chapter will trace the development of the Company‟s rise to power in Bengal, the articulation of commercial policies in the context of Mercantilism that developed as an informing ideology in Europe and that found limited application in India by some of the Company‟s officials. -

History of Modern Maharashtra (1818-1920)

1 1 MAHARASHTRA ON – THE EVE OF BRITISH CONQUEST UNIT STRUCTURE 1.0 Objectives 1.1 Introduction 1.2 Political conditions before the British conquest 1.3 Economic Conditions in Maharashtra before the British Conquest. 1.4 Social Conditions before the British Conquest. 1.5 Summary 1.6 Questions 1.0 OBJECTIVES : 1 To understand Political conditions before the British Conquest. 2 To know armed resistance to the British occupation. 3 To evaluate Economic conditions before British Conquest. 4 To analyse Social conditions before the British Conquest. 5 To examine Cultural conditions before the British Conquest. 1.1 INTRODUCTION : With the discovery of the Sea-routes in the 15th Century the Europeans discovered Sea route to reach the east. The Portuguese, Dutch, French and the English came to India to promote trade and commerce. The English who established the East-India Co. in 1600, gradually consolidated their hold in different parts of India. They had very capable men like Sir. Thomas Roe, Colonel Close, General Smith, Elphinstone, Grant Duff etc . The English shrewdly exploited the disunity among the Indian rulers. They were very diplomatic in their approach. Due to their far sighted policies, the English were able to expand and consolidate their rule in Maharashtra. 2 The Company’s government had trapped most of the Maratha rulers in Subsidiary Alliances and fought three important wars with Marathas over a period of 43 years (1775 -1818). 1.2 POLITICAL CONDITIONS BEFORE THE BRITISH CONQUEST : The Company’s Directors sent Lord Wellesley as the Governor- General of the Company’s territories in India, in 1798. -

Shivaji the Founder of Maratha Swaraj

26 B. I. S. M. Puraskrita Grantha Mali, No. SHIVAJI THE FOUNDER OF MARATHA SWARAJ BY C. V. VAIDYA, M. A., LL. B. Fellow, University of Bombay, Vice-Ctianct-llor, Tilak University; t Bharat-Itihasa-Shamshndhak Mandal, Poona* POON)k 1931 PRICE B8. 3 : B. Printed by S. R. Sardesai, B. A. LL. f at the Navin ' * Samarth Vidyalaya's Samarth Bharat Press, Sadoshiv Peth, Poona 2. BY THE SAME AUTHOR : Price Rs* as. Mahabharat : A Criticism 2 8 Riddle of the Ramayana ( In Press ) 2 Epic India ,, 30 BOMBAY BOOK DEPOT, BOMBAY History of Mediaeval Hindu India Vol. I. Harsha and Later Kings 6 8 Vol. II. Early History of Rajputs 6 8 Vol. 111. Downfall of Hindu India 7 8 D. B. TARAPOREWALLA & SONS History of Sanskrit Literature Vedic Period ... ... 10 ARYABHUSHAN PRESS, POONA, AND BOOK-SELLERS IN BOMBAY Published by : C. V. Vaidya, at 314. Sadashiv Peth. POONA CITY. INSCRIBED WITH PERMISSION TO SHRI. BHAWANRAO SHINIVASRAO ALIAS BALASAHEB PANT PRATINIDHI,B.A., Chief of Aundh In respectful appreciation of his deep study of Maratha history and his ardent admiration of Shivaji Maharaj, THE FOUNDER OF MARATHA SWARAJ PREFACE The records in Maharashtra and other places bearing on Shivaji's life are still being searched out and collected in the Shiva-Charitra-Karyalaya founded by the Bharata- Itihasa-Samshodhak Mandal of Poona and important papers bearing on Shivaji's doings are being discovered from day to day. It is, therefore, not yet time, according to many, to write an authentic lifetof this great hero of Maha- rashtra and 1 hesitated for some time to undertake this work suggested to me by Shrimant Balasaheb Pant Prati- nidhi, Chief of Aundh.