What Makes Popular Christian Music

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rolling Stone Magazine's Top 500 Songs

Rolling Stone Magazine's Top 500 Songs No. Interpret Title Year of release 1. Bob Dylan Like a Rolling Stone 1961 2. The Rolling Stones Satisfaction 1965 3. John Lennon Imagine 1971 4. Marvin Gaye What’s Going on 1971 5. Aretha Franklin Respect 1967 6. The Beach Boys Good Vibrations 1966 7. Chuck Berry Johnny B. Goode 1958 8. The Beatles Hey Jude 1968 9. Nirvana Smells Like Teen Spirit 1991 10. Ray Charles What'd I Say (part 1&2) 1959 11. The Who My Generation 1965 12. Sam Cooke A Change is Gonna Come 1964 13. The Beatles Yesterday 1965 14. Bob Dylan Blowin' in the Wind 1963 15. The Clash London Calling 1980 16. The Beatles I Want zo Hold Your Hand 1963 17. Jimmy Hendrix Purple Haze 1967 18. Chuck Berry Maybellene 1955 19. Elvis Presley Hound Dog 1956 20. The Beatles Let It Be 1970 21. Bruce Springsteen Born to Run 1975 22. The Ronettes Be My Baby 1963 23. The Beatles In my Life 1965 24. The Impressions People Get Ready 1965 25. The Beach Boys God Only Knows 1966 26. The Beatles A day in a life 1967 27. Derek and the Dominos Layla 1970 28. Otis Redding Sitting on the Dock of the Bay 1968 29. The Beatles Help 1965 30. Johnny Cash I Walk the Line 1956 31. Led Zeppelin Stairway to Heaven 1971 32. The Rolling Stones Sympathy for the Devil 1968 33. Tina Turner River Deep - Mountain High 1966 34. The Righteous Brothers You've Lost that Lovin' Feelin' 1964 35. -

BSMA 2019 Powerpoint Choir B

BSMA 2019 SING! Soloists Some words they can’t be spoken only sung, So hear a thousand voices shouting love. There’s a place, there’s a time in this life When you sing what you are feeling, Find your feet, stand your ground, Don’t you see right now the world is listening to what we say? All Sing Sing it louder, sing it clearer, knowing everyone will hear you, Make some noise, find your voice tonight. Sing it stronger, sing together, make this moment last forever, Old and young shouting love tonight. To sing we’ve had a lifetime to wait (wait, wait, wait) And see a thousand faces celebrate (we have to celebrate) You brought hope, you brought light, Conquered fear, no it wasn’t always easy, Stood your ground, kept your faith, Don’t you see right now the world is listening to what we say? Sing it louder, sing it clearer, knowing everyone will hear you, Make some noise, find your voice tonight. Sing it stronger, sing together, make this moment last forever, Old and young shouting love tonight. Some words they can’t be spoken only sung, To hear a thousand voices shouting love and life and hope. Soloists Just sing; just sing; just sing; just sing. Choir –Come on and Sing it louder, sing it clearer, knowing everyone will Hear you, Make some noise, find your voice tonight, Sing it stronger, sing together make this moment last forever. Old and young shouting love tonight. Soloists – Hear a thousand voices shouting love Danny Boy Oh Danny Boy, the pipes, the pipes are calling, From glen to glen and down the mountain side. -

2015 ANNUAL REPORT Pictured (Top to Bottom, L-R)

OUR 2015 ANNUAL REPORT Pictured (top to bottom, l-r): Shawn Patterson and vocalist Sammy Allen at the 2015 ASCAP Film & TV Music Awards Latin Heritage Award honorees La Original Banda el Limón at the 2015 ASCAP Latin Music Awards ASCAP Golden Note Award honoree Lauryn Hill at the 2015 R&S Awards Lady Antebellum at the 2015 ASCAP Country Music Awards Dave Grohl congrat- ulates Gene Simmons and Paul Stanley on their ASCAP Found- ers Award at the 2015 ASCAP Pop Awards Cast members from Invisible Thread with Richard Rodgers New Horizons Award winners Matt Gould (at piano) & Griffin Matthews (far right) at the 2015 ASCAP Foundation Awards The American Con- temporary Music En- semble (ACME) at the 2015 ASCAP Concert Music Awards Annual Report design by Mike Vella 2015 Annual Report Contents 4 16 OUR MISSION Our ASCAP Our Success We are the world leader in performance 6 18 royalties, advocacy and service for Our Growth Our Celebration songwriters, composers and music publishers. Our mission is to ensure that 8 20 Our Board Our Licensing our music creator members can thrive Partners alongside the businesses who use our 10 music, so that together, we can touch Our Advocacy 22 Our Commitment the lives of billions. 12 Our Innovation 24 Our Communication 14 Our Membership 25 Financial Overview 3 OUR ASCAP USIC IS AN ART. AND MUSIC IS A BUSINESS. The beauty of ASCAP, as conceived by our visionary founders over 100 years ago, is that it serves to foster both music and commerce so that each partner in this relationship can flourish. -

Praise & Worship from Moody Radio

Praise & Worship from Moody Radio 04/28/15 Tuesday 12 A (CT) Air Time (CT) Title Artist Album 12:00:10 AM Hold Me Jesus Big Daddy Weave Every Time I Breathe (2006) 12:03:59 AM Do Something Matthew West Into The Light 12:07:59 AM Wonderful Merciful Savior Selah Press On (2001) 12:12:20 AM Jesus Loves Me Chris Tomlin Love Ran Red (2014) 12:15:45 AM Crown Him With Many Crowns Michael W. Smith/Anointed I'll Lead You Home (1995) 12:21:51 AM Gloria Todd Agnew Need (2009) 12:24:36 AM Glory Phil Wickham The Ascension (2013) 12:27:47 AM Do Everything Steven Curtis Chapman Do Everything (2011) 12:31:29 AM O Love Of God Laura Story God Of Every Story (2013) 12:34:26 AM Hear My Worship Jaime Jamgochian Reason To Live (2006) 12:37:45 AM Broken Together Casting Crowns Thrive (2014) 12:42:04 AM Love Has Come Mark Schultz Come Alive (2009) 12:45:49 AM Reach Beyond Phil Stacey/Chris August Single (2015) 12:51:46 AM He Knows Your Name Denver & the Mile High Orches EP 12:55:16 AM More Than Conquerors Rend Collective The Art Of Celebration (2014) Praise & Worship from Moody Radio 04/28/15 Tuesday 1 A (CT) Air Time (CT) Title Artist Album 1:00:08 AM You Are My All In All Nichole Nordeman WOW Worship: Yellow (2003) 1:03:59 AM How Can It Be Lauren Daigle How Can It Be (2014) 1:08:12 AM Truth Calvin Nowell Start Somewhere 1:11:57 AM The One Aaron Shust Morning Rises (2013) 1:15:52 AM Great Is Thy Faithfulness Avalon Faith: A Hymns Collection (2006) 1:21:50 AM Beyond Me Toby Mac TBA (2015) 1:25:02 AM Jesus, You Are Beautiful Cece Winans Throne Room 1:29:53 AM No Turning Back Brandon Heath TBA (2015) 1:32:59 AM My God Point of Grace Steady On 1:37:28 AM Let Them See You JJ Weeks Band All Over The World (2009) 1:40:46 AM Yours Steven Curtis Chapman This Moment 1:45:28 AM Burn Bright Natalie Grant Hurricane (2013) 1:51:42 AM Indescribable Chris Tomlin Arriving (2004) 1:55:27 AM Made New Lincoln Brewster Oxygen (2014) Praise & Worship from Moody Radio 04/28/15 Tuesday 2 A (CT) Air Time (CT) Title Artist Album 2:00:09 AM Beautiful MercyMe The Generous Mr. -

People & Places NEWS/FEATURES

ARAB TIMES, FRIDAY-SATURDAY, AUGUST 13-14, 2021 NEWS/FEATURES 13 People & Places Siham Mustafa as Nermeen in a scene from the fi lm ‘Our River … Our Sky,’ which is co-produced by Talal Al-Muhanna through his Kuwaiti company Linked Productions. Obit Film An end of an era Baghdad-set fi lm tells stories of ordinary people Pat, daughter of Alfred Kuwaiti producer’s fi lm to debut in Sarajevo Hitchcock, dies aged 93 KUWAIT CITY, Aug 12: An versity professor, Irada Al-Jubori ing some very intense periods of NEW YORK, Aug 12, (AP): Patricia Hitchcock internationally co-produced fea- — won the $100,000 IWC Schaf- sectarian violence in Iraq in 2006 O’Connell, the only child of Alfred Hitchcock and an ture fi lm directed by Maysoon fhausen script prize at Dubai In- and 2007. In many ways, Irada actor herself who made a memorable appearance in Pachachi — a London-based fi lm- ternational Film Festival in 2012, felt unable to write fi ction at the her father’s “Strangers on a Train” and championed maker of Iraqi origin — will have awarded to the fi lmmaker by Head time, when real life itself was so his work in the decades following his death, has died its world premiere at the pres- of Jury Cate Blanchett. Says fi lm- terrifying and awful. An underly- at age 93. tigious Sarajevo Film Festival in maker Maysoon Pachachi: “This Hitchcock died Monday in her sleep at home in ing theme of our fi lm is about how Thousand Oaks, California, her daughter Tere Car- Bosnia & Herzegovina in August. -

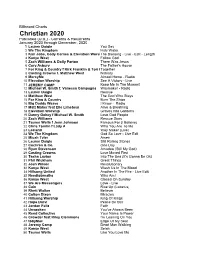

Christian 2020

Billboard Charts Christian 2020 Published (U.S.) - Currents & Recurrents January 2020 through December, 2020 1 Lauren Daigle You Say 2 We The Kingdom Holy Water 3 Kari Jobe, Cody Carnes & Elevation WorshipThe Blessing - Live - Edit - Length 4 Kanye West Follow God 5 Zach Williams & Dolly Parton There Was Jesus 6 Cory Asbury The Father's House 7 For King & Country f Kirk Franklin & Tori KellyTogether 8 Casting Crowns f. Matthew West Nobody 9 MercyMe Almost Home - Radio 10 Elevation Worship See A Victory - Live 11 JEREMY CAMP Keep Me In The Moment 12 Michael W. Smith f. Vanessa Campagna Waymaker - Radio 13 Lauren Daigle Rescue 14 Matthew West The God Who Stays 15 For King & Country Burn The Ships 16 Big Daddy Weave I Know - Radio 17 Matt Maher feat Elle Limebear Alive & Breathing 18 Elevation Worship Graves Into Gardens 19 Danny Gokey f Michael W. Smith Love God People 20 Zach Williams Rescue Story 21 Tauren Wells f Jenn Johnson Famous For (I Believe) 22 Chris Tomlin f Lady A Who You Are To Me 23 Leeland Way Maker (Live) 24 We The Kingdom God So Love - Live Edit 25 Micah Tyler Amen 26 Lauren Daigle Still Rolling Stones 27 Cochren & Co. One Day 28 Ryan Stevenson Amadeo (Still My God) 29 Casting Crowns Love Moved First 30 Tasha Layton Into The Sea (It's Gonna Be Ok) 31 Phil Wickham Great Things 32 Josh Wilson Revolutionary 32 Kanye West Wash Us In The Blood 34 Hillsong United Another In The Fire - Live Edit 35 Needtobreathe Who Am I 36 Kanye West Closed On Sunday 37 We Are Messengers Love - Live 38 Cain Rise Up (Lazarus) 39 Rhett Walker Believer -

Gospel with a Groove

Southeastern University FireScholars Selected Honors Theses Spring 4-28-2017 Gospel with a Groove: A Historical Perspective on the Marketing Strategies of Contemporary Christian Music in Relation to its Evangelistic Purpose with Recommendations for Future Outreach Autumn E. Gillen Southeastern University - Lakeland Follow this and additional works at: http://firescholars.seu.edu/honors Part of the Christianity Commons, Liturgy and Worship Commons, Marketing Commons, Music Commons, and the Practical Theology Commons Recommended Citation Gillen, Autumn E., "Gospel with a Groove: A Historical Perspective on the Marketing Strategies of Contemporary Christian Music in Relation to its Evangelistic Purpose with Recommendations for Future Outreach" (2017). Selected Honors Theses. 76. http://firescholars.seu.edu/honors/76 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by FireScholars. It has been accepted for inclusion in Selected Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of FireScholars. For more information, please contact [email protected]. GOSPEL WITH A GROOVE: A HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVE ON THE MARKETING STRATEGIES OF CONTEMPORARY CHRISTIAN MUSIC IN RELATION TO ITS EVANGELISTIC PURPOSE WITH RECOMMENDATIONS FOR FUTURE OUTREACH by Autumn Elizabeth Gillen Submitted to the Honors Program Committee in partial fulfillment of the requirements for University Honors Scholars Southeastern University 2017 GOSPEL WITH A GROOVE 2 Copyright by Autumn Elizabeth Gillen 2017 GOSPEL WITH A GROOVE 3 Abstract Contemporary Christian Music (CCM) is an effective tool for the evangelism of Christianity. With its origins dating back to the late 1960s, CCM resembles musical styles of popular-secular culture while retaining fundamental Christian values in lyrical content. This historical perspective of CCM marketing strategies, CCM music television, CCM and secular music, arts worlds within CCM, and the science of storytelling in CCM aims to provide readers with the context and understanding of the significant role that CCM plays in modern-day evangelism. -

My Town: Writers on American Cities

MY TOW N WRITERS ON AMERICAN CITIES MY TOWN WRITERS ON AMERICAN CITIES CONTENTS INTRODUCTION by Claire Messud .......................................... 2 THE POETRY OF BRIDGES by David Bottoms ........................... 7 GOOD OLD BALTIMORE by Jonathan Yardley .......................... 13 GHOSTS by Carlo Rotella ...................................................... 19 CHICAGO AQUAMARINE by Stuart Dybek ............................. 25 HOUSTON: EXPERIMENTAL CITY by Fritz Lanham .................. 31 DREAMLAND by Jonathan Kellerman ...................................... 37 SLEEPWALKING IN MEMPHIS by Steve Stern ......................... 45 MIAMI, HOME AT LAST by Edna Buchanan ............................ 51 SEEING NEW ORLEANS by Richard Ford and Kristina Ford ......... 59 SON OF BROOKLYN by Pete Hamill ....................................... 65 IN SEATTLE, A NORTHWEST PASSAGE by Charles Johnson ..... 73 A WRITER’S CAPITAL by Thomas Mallon ................................ 79 INTRODUCTION by Claire Messud ore than three-quarters of Americans live in cities. In our globalized era, it is tempting to imagine that urban experiences have a quality of sameness: skyscrapers, subways and chain stores; a density of bricks and humanity; a sense of urgency and striving. The essays in Mthis collection make clear how wrong that assumption would be: from the dreamland of Jonathan Kellerman’s Los Angeles to the vibrant awakening of Edna Buchanan’s Miami; from the mid-century tenements of Pete Hamill’s beloved Brooklyn to the haunted viaducts of Stuart Dybek’s Pilsen neighborhood in Chicago; from the natural beauty and human diversity of Charles Johnson’s Seattle to the past and present myths of Richard Ford’s New Orleans, these reminiscences and musings conjure for us the richness and strangeness of any individual’s urban life, the way that our Claire Messud is the author of three imaginations and identities and literary histories are intertwined in a novels and a book of novellas. -

Presents April 25, 2021 Macel Falwell Recital Hall MUSIC

presents April 25, 2021 Macel Falwell Recital Hall MUSIC 305 6:00 PM Che Faró Senza Euridice? Christoph Willibald Gluck from Orfeo ed Euridice (1714-1787) Se tu m’ami, se sospiri Giovanni Battista Pergolesi (1710-1736) Seligkeit Franz Schubert (1797-1828) The Green Dog Herbert Kingsley Far from the Home I Love Jerry Bock (1928-2010) from Fiddler on the Roof (©1964) Sheldon Harnick (b. 1924) Something Wonderful Richard Rodgers (1902-1979) from The King and I (©1951) Oscar Hammerstein II (1895-1960) Never Lost Chris Brown, Steven Furtick, and Tiffany Hammer Elizabeth Rajcok, piano Everything Lauren Daigle, Jason Ingram, and Paul Mabury Che Faro Senza Euridice “Che Faró Senza Euridice” is an aria from Act III of the Italian tragic opera Orfeo ed Euridice that was inspired by the myth of Orpheus. The opera was composed by Christoph Gluck, and the libretto was written by Ranieri de’ Calzabigi. The opera premiered at the Burgtheater in Vienna in October of 1762. “Che Faró Senza Euridice” takes place in Hades after Orfeo goes to rescue his beloved Euridice; however, the only way Euridice can escape is if Orfeo does not look at her until they have left Hades. Euridice becomes distressed, so Orfeo turns to look at her. As he does, Euridice dies and falls to the ground at his feet. In “Che Faró Senza Euridice”, Orfeo expresses his desperation and mourns for his Euridice. Che farò senza Euridice? What will I do without Euridice? Dove andrò senza il mio ben? Where will I go without my wonderful one? Euridice! Oh Dio! Rispondi! Euridice! Oh, God! Answer! Io son pure il tuo fedele. -

Dolly Parton Brings a Word of Her Own to Popular Mobile Game Words with Friends

Zynga Logo Dolly Parton Brings A Word Of Her Own To Popular Mobile Game Words With Friends October 23, 2020 Beloved Entertainer and International Icon Featured Within Hit Game Promoting Her New Book SONGTELLER: My Life In Lyrics SAN FRANCISCO--(BUSINESS WIRE)--Oct. 23, 2020-- Today, Zynga Inc. (Nasdaq: ZNGA) a global leader in interactive entertainment, announced that global superstar Dolly Parton, will contribute her own newly-coined word as ‘Word Of The Day’ for the hit mobile game, Words With Friends: Songteller. This specially crafted word, describing Parton’s record-breaking career in music and life as a lyricist, also happens to be the title of her new lyric book. This press release features multimedia. View the full release here: https://www.businesswire.com/news/home/20201023005008/en/ “Dolly Parton is more than a musician. She is a source of inspiration, joy and comfort for people around the world, of all ages, and from every walk of life,” said Bernard Kim, President of Publishing for Zynga. “While there is no one phrase that can define this one-of-a-kind icon, we’re honored to add Dolly’s own word, Songteller, to our dictionary to celebrate her illustrious, distinctive life.” Players who enter the game on October 23rd can access a special video message from Dolly Parton explaining the meaning of ‘Songteller’, her specially coined description of her life and career in music. In the game, fans will also be directed to Dolly Parton’s new talkshoplive® channel where Dolly will host a livestream at 6PM ET on October 23rd, to share anecdotes from her life and memoir. -

Still Rolling Stones Matthew 28:1-10

Still Rolling Stones Matthew 28:1-10 Resurrection of the Lord/ 21st April 2019 Only Matthew tells us how the stone was moved. Mark tells us that when the women arrived at the tomb the stone had already been rolled back (Mk. 16:4). Luke says the same (Lk. 24:3). Even John, who is usually a “horse of a different color,” agrees with both Mark and Luke (Jn. 20:1). Matthew is different. Matthew is far more dramatic. Matthew tells us that when the two Marys arrived at the tomb, it was still sealed. In fact, unique to Matthew, we’re told that Pilate stationed a guard of soldiers at the tomb, commanding them to, “…make it as secure as you can” (Mt. 27:65). So they made the tomb secure by sealing the stone (Mt. 27:66). A sealed stone. That’s what the women found on the day after the Sabbath, at the dawn of a new week—which was also, they soon discovered, the dawn of the new eon of God’s grace and justice. For what they didn’t know was that something had already taken place behind that securely sealed stone. Suddenly, the earth began to tremble and shake. I should say, shake again. Matthew tells us that when Jesus “cried with a loud voice and breathed his last” on the cross, “The earth shook, and the rocks were split” (Mt. 27:51). When the centurion and others standing at the cross saw (and felt) the earthquake, they were terrified and said, “Truly this man was God’s Son!” (Mt. -

An Examination of Contemporary Christian Music Success Within Mainstream Rock and Country Billboard Charts Megan Marie Carlan

Pace University DigitalCommons@Pace Honors College Theses Pforzheimer Honors College 8-21-2019 An Examination of Contemporary Christian Music Success Within Mainstream Rock and Country Billboard Charts Megan Marie Carlan Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.pace.edu/honorscollege_theses Part of the Music Business Commons An Examination of Contemporary Christian Music Success Within Mainstream Rock and Country Billboard Charts By Megan Marie Carlan Arts and Entertainment Management Dr. Theresa Lant Lubin School of Business August 21, 2019 Abstract Ranging from inspirational songs void of theological language to worship music imbued with overt religious messages, Contemporary Christian Music (CCM) has a long history of being ill-defined. Due to the genre’s flexible nature, many Christian artists over the years have used vague imagery and secular lyrical content to find favor among mainstream outlets. This study examined the most recent ten-year period of CCM to determine its ability to cross over into the mainstream music scene, while also assessing the impact of its lyrical content and genre on the probability of reaching such mainstream success. For the years 2008-2018, Billboard data were collected for every Christian song on the Hot 100, Hot Rock Songs, or Hot Country Songs in order to detect any noticeable trend regarding the rise or fall of CCM; each song then was coded for theological language. No obvious trend emerged regarding the mainstream success of CCM as a whole, but the genre of Rock was found to possess the greatest degree of mainstream success. Rock also, however, was shown to have a very low tolerance for theological language, contrasted with the high tolerance of Country.