Chapter I Rochdale Before Domesday

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Heywood Distribution Park OL10 2TT, Greater Manchester

Heywood Distribution Park OL10 2TT, Greater Manchester TO LET - 148,856 SQ FT New self-contained production /distribution unit Award winning 24 hour on-site security, CCTV and gatehouse entry 60m service yard 11 dock and two drive in loading doors 1 mile from M66/J3 4 miles from M62/J18 www.heywoodpoint.co.uk Occupiers include: KUEHNE+NAGEL DPD Group Wincanton K&N DFS M66 / M62 Fowler Welch Krispy Kreme Footasylum Eddie Stobart Paul Hartmann 148,000 sq ft Argos AVAILABLE NOW Main Aramex Entrance Moran Logistics Iron Mountain 60m 11 DOCK LEVELLERS LEVEL ACCESS LEVEL ACCESS 148,856 sq ft self-contained distribution building Schedule of accommodation TWO STOREY OFFICES STOREY TWO Warehouse 13,080 sq m 140,790 sq ft Ground floor offices 375 sq m 4,033 sq ft 90.56m First floor offices 375 sq m 4,033 sq ft 148,000 sq ft Total 13,830 sq m 148,856 sq ft SPACES PARKING 135 CAR 147.65m Warehouse Offices External Areas 5 DOCK LEVELLERS 50m BREEAM “very good” 11 dock level access doors Fully finished to Cat A standard LEVEL ACCESS 60m service yardLEVEL ACCESS EPC “A” rating 2 level access doors 8 person lift 135 dedicated car parking spaces 12m clear height 745kVA electricity supply Heating and comfort cooling Covered cycle racks 50kN/sqm floor loading 15% roof lights 85.12m 72.81m TWO STOREY OFFICES 61 CAR PARKING SPACES M66 Rochdale Location maps Bury A58 Bolton A58 M62 A56 A666 South Heywood link road This will involve the construction of a new 1km road between the motorway junction and A58 M61 Oldham A new link road is proposed which will Hareshill Road, together with the widening M60 A576 M60 provide a direct link between Heywood and upgrading of Hareshill Road. -

The Royal Oldham Hospital, OL1

The Royal Oldham Hospital, OL1 2JH Travel Choices Information – Patient and Visitor Version Details Notes and Links Site Map Site Map – Link to Pennine Acute website Bus Stops, Services Bus Stops are located on the roads alongside the hospital site and are letter and operators coded. The main bus stops are on Rochdale Road and main bus service is the 409 linking Rochdale, Oldham and Ashton under Lyne. Also, see further Bus Operators serving the hospital are; information First Greater Manchester or on Twitter following. Rosso Bus Stagecoach Manchester or on Twitter The Transport Authority and main source of transport information is; TfGM or on Twitter ; TfGM Bus Route Explorer (for direct bus routes); North West Public Transport Journey Planner Nearest Metrolink The nearest stops are at Oldham King Street or Westwood; Tram Stops Operator website, Metrolink or on Twitter Transport Ticketing Try the First mobile ticketing app for smartphones, register and buy daily, weekly, monthly or 10 trip bus tickets on your phone, click here for details. For all bus operator, tram and train tickets, visit www.systemonetravelcards.co.uk. Local Link – Users need to be registered in advance (online or by phone) and live within Demand Responsive the area of service operation. It can be a minimum of 2 hours from Door to Door registering to booking a journey. Check details for each relevant service transport (see leaflet files on website, split by borough). Local Link – Door to Door Transport (Hollinwood, Coppice & Werneth) Ring and Ride Door to door transport for those who find using conventional public transport difficult. -

Walk the Way in a Day Walk 44 Millstone Edge and Blackstone Edge

Walk the Way in a Day Walk 44 Millstone Edge and Blackstone Edge A long walk following the Pennine Way through a 1965 - 2015 landscape of rugged charm, with moorland paths running along Millstone Grit scarps. The return route follows tracks and lanes through the Saddleworth area, with its scatter of reservoirs, functional villages and untidy farmsteads. Length: 17½ miles (28 kilometres) Ascent: 2,704 feet (825 metres) Highest Point: 472 metres (1,549 feet) Map(s): OS Explorer OL Maps 1 (‘The Peak District - Dark Peak’) (West Sheet) and 21 (‘South Pennines’) (South Sheet) Starting Point: Standedge parking area, Saddleworth (SE 019 095) Facilities: Inn nearby. Website: http://www.nationaltrail.co.uk/pennine-way/route/walk- way-day-walk-44-millstone-edge-and-blackstone-edge Millstone Edge The starting point is located at the west end of the Standedge Cutting on the A62. The first part of the walk follows the Pennine Way north-west along Millstone Edge for 3¼ miles (5¼ kilometres). Crossing straight over the busy main road, a finger sign points along a hardcore track. Soon another sign marks a right turn over a fence stile, joining a path running along the edge of the moorland plateau towards an OS pillar (1 = SE 012 104). Standedge Standedge has long been an important transportation route. Since 1811, the Huddersfield Narrow Canal has run through a tunnel beneath the Pennine ridge, connecting Marsden in the Colne Walk 44: Millstone Edge and Blackstone Edge page 1 Valley and Diggle in Saddleworth. This was joined in 1849 by a direction, crossing a mossy area (Green Hole Hill) as it swings around to railway tunnel, which at around 3 miles (5 kilometres) was then head north-north-west, following the broad ridge down towards the A672. -

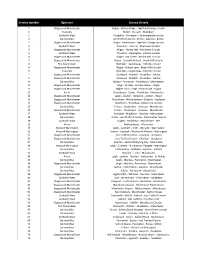

Sept 2020 All Local Registered Bus Services

Service number Operator Service Details 1 Stagecoach Manchester Wigan - Marus Bridge - Highfield Grange Circular 1 Transdev Bolton - Darwen - Blackburn 1 Go North West Piccadilly - Chinatown - Spinningfields circular 2 Diamond Bus intu Trafford Centre - Eccles - Swinton - Bolton 2 Stagecoach Manchester Wigan - Pemberton - Highfield Grange circular 2 Go North West Piccadilly - Victoria - Deansgate circular 3 Stagecoach Manchester Wigan - Norley Hall - Kitt Green Circular 3 Go North West Piccadilly - Deansgate - Victoria circular 4 Stagecoach Manchester Wigan - Kitt Green - Norley Hall Circular 5 Stagecoach Manchester Wigan - Springfield Road - Beech Hill Circular 6 First Manchester Rochdale - Queensway - Kirkholt circular 6 Stagecoach Manchester Wigan - Gidlow Lane - Beech Hill Circular 6 Transdev Rochdale - Queensway - Kirkholt circular 7 Stagecoach Manchester Stockport - Reddish - Droyslden - Ashton 7 Stagecoach Manchester Stockport - Reddish - Droylsden - Ashton 8 Diamond Bus Bolton - Farnworth - Pendlebury - Manchester 8 Stagecoach Manchester Leigh - Hindley - Hindley Green - Wigan 9 Stagecoach Manchester Higher Folds - Leigh - Platt Bridge - Wigan 10 Arriva Brookhouse - Eccles - Pendleton - Manchester 10 Stagecoach Manchester Leigh - Lowton - Golborne - Ashton - Wigan 11 Stagecoach Manchester Altrincham - Wythenshawe - Cheadle - Stockport 12 Stagecoach Manchester Middleton - Boarshaw - Moorclose circular 15 Diamond Bus Flixton - Davyhulme - Urmston - Manchester 15 Stagecoach Manchester Flixton - Davyhulme - Urmston - Manchester 17 -

17 Times Changed 17 17A

From 3 September Buses Replacement 17 Times changed 17 17A Easy access on all buses Rochdale Sudden Castleton Middleton Blackley Harpurhey Collyhurst Manchester From 3 September 2017 For public transport information phone 0161 244 1000 7am – 8pm Mon to Fri 8am – 8pm Sat, Sun & public holidays Operated by This timetable is available online at First Manchester www.tfgm.com PO Box 429, Manchester, M60 1HX ©Transport for Greater Manchester 17–1284–G17–7000–0817 Additional information Alternative format Operator details To ask for leaflets to be sent to you, or to request First Manchester large print, Braille or recorded information Wallshaw Street, Oldham, OL1 3TR phone 0161 244 1000 or visit www.tfgm.com Telephone 0161 627 2929 Easy access on buses Travelshops Journeys run with low floor buses have no Manchester Piccadilly Gardens steps at the entrance, making getting on Mon to Sat 7am to 6pm and off easier. Where shown, low floor Sunday 10am to 6pm buses have a ramp for access and a dedicated Public hols 10am to 5.30pm space for wheelchairs and pushchairs inside the Manchester Shudehill Interchange bus. The bus operator will always try to provide Mon to Sat 7am to 7.30pm easy access services where these services are Sunday* 10am to 1.45pm and 2.30pm to 5.30pm scheduled to run. Middleton Bus Station Mon to Sat 8.30am to 1.15pm and 2pm to 4pm Using this timetable Sunday* Closed Timetables show the direction of travel, bus Rochdale Interchange numbers and the days of the week. Mon to Fri 7am to 5.30pm Main stops on the route are listed on the left. -

Migrant Workers in Rochdale and Oldham Scullion, LC, Steele, a and Condie, J

Migrant workers in Rochdale and Oldham Scullion, LC, Steele, A and Condie, J Title Migrant workers in Rochdale and Oldham Authors Scullion, LC, Steele, A and Condie, J Type Monograph URL This version is available at: http://usir.salford.ac.uk/id/eprint/9261/ Published Date 2008 USIR is a digital collection of the research output of the University of Salford. Where copyright permits, full text material held in the repository is made freely available online and can be read, downloaded and copied for non-commercial private study or research purposes. Please check the manuscript for any further copyright restrictions. For more information, including our policy and submission procedure, please contact the Repository Team at: [email protected]. Migrant Workers in Rochdale and Oldham Final report Lisa Hunt, Andy Steele and Jenna Condie Salford Housing & Urban Studies Unit University of Salford August 2008 About the Authors Lisa Hunt is a Research Fellow in the Salford Housing & Urban Studies Unit (SHUSU) at the University of Salford. Andy Steele is Professor of Housing & Urban Studies and Director of the Salford Housing & Urban Studies Unit (SHUSU) at the University of Salford. Jenna Condie is a Research Assistant in the Salford Housing & Urban Studies Unit (SHUSU) at the University of Salford. The Salford Housing & Urban Studies Unit is a dedicated multi-disciplinary research and consultancy unit providing a range of services relating to housing and urban management to public and private sector clients. The Unit brings together researchers drawn from a range of disciplines including: social policy, housing management, urban geography, environmental management, psychology, social care and social work. -

Hooley Bridge Mills, Heywood, Rochdale, Greater Manchester

Hooley Bridge Mills, Heywood, Rochdale, Greater Manchester Archaeological Watching Brief Oxford Archaeology North April 2009 United Utilities Issue No: 2008/09-909 OAN Job No: L9800 NGR: SD 8536 1164 Hooley Bridge Mills, Heywood, Rochdale, Greater Manchester: Watching Brief 1 CONTENTS SUMMARY .................................................................................................................. 3 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS .............................................................................................. 4 1. INTRODUCTION ..................................................................................................... 5 1.1 Circumstances of Project................................................................................. 5 2. METHODOLOGY .................................................................................................... 6 2.1 Project Design................................................................................................. 6 2.2 Rapid Desk-Based Research............................................................................ 6 2.3 Watching Brief................................................................................................ 6 2.4 Archive........................................................................................................... 7 3. BACKGROUND ....................................................................................................... 8 3.1 Location, Topography and Geology ............................................................... -

Free Buses to Middleton and Rochdale Campuses 2019/20

Free buses to Middleton and Rochdale campuses 2019/20 H1 FROM OLDHAM H2 FROM BROADWAY H3 FROM BURY H4 FROM MILNROW Oldham Rd/Kingsway Stand F . 7:40 Broadway, Gorse Mill (Opposite Litecraft) . 7:25 Bus Terminus, Market Street, Tottington . 7:30 Kiln Lane, opposite Tim Bobbin . 7:45 OL16 4SZ OL9 9RJ Next Door Restaurant, BL8 3LL Ol16 3LH Halfway House Royton . 7:45 Whitegate, Broadway . 7:30 Wetherspoons Art Picture House . 7:45 Hollingworth Road, Smithybridge . 7:50 Highbarn St Royton . 7:53 Oldham Road/Broadway . 7:35 (Opposite Bus Station) BL9 0AY Lake Bank . 7:52 Milnrow Rd/Bridge St Shaw . 8:00 Oldham Road/Ashton Road West . 7:38 Bury New Road, Summit . 7:55 Littleborough Centre, (Wheatsheaf Pub) . 7:55 Elizabethan Way Milnrow . 8:07 Ashton Road East/Westminster Road . 7:43 Dawson Street, Heywood . 7:59 Halifax Road, Dearnley . 8:00 Rochdale Road Firgrove . 8:08 Hollinwood Crem, Roman Road . 7:45 Middleton Road, Hopwood . 8:01 Birch Road . 8:05 Kingsway Retail Park . 8:15 Oasis Academy, Hollins Road . 7:48 Hollin Lane . 8:05 Wardle Road . 8:10 Kingsway Turf Hill . 8:20 Honeywell Centre, Ashton Road . 7:50 Windermere Road, Langley . 8:07 Halifax Road . 8:20 Queensway Castleton . 8:25 Stand C, Oldham Bus Station . 8:00 Bowness Road, Langley . 8:13 Newgate (Rochdale Campus) . 8:25 Middleton Campus . 8:35 Middleton Road/Broadway . 8:05 Wood Street/Eastway, Langley . 8:15 Manchester Road, Sudden . 8:30 Middleton Road/Firwood Park . 8:08 Rochdale Road . 8:21 Manchester Road, Slattocks . -

Pennine Drive, Milnrow, Rochdale

PENNINE DRIVE, MILNROW, ROCHDALE Asking Price Of: £200,000 FEATURES No Chain Semi-Detached Property Three Bedrooms Attic Room Large Corner Plot Further Development Potential Driveway Parking DG, GCH & Alarm Well Presented Throughout Viewings Recommended *** NO CHAIN / SEMI-DETACHED PROPERTY / THREE BEDROOMS PLUS ATTIC ROOM / LOUNGE DINER / ENTRANCE HALL / MODERN KITCHEN & BATHROOM / LARGE CORNER PLOT OFFERING FURTHER DEVELOPMENT POTENTIAL / DRIVEWAY PARKING / DG, GCH & ALARM *** We are pleased to offer for sale this well presented three bedroom plus attic room semi-detached property standing on a large corner plot which offers further development potential. Situated in a popular residential location offering good access to local amenities including shops, schools and public transport links (including M62 motorway connection and Manchester Metrolink service). The property benefits from double glazing, gas central heating and security alarm with the accommodation comprising briefly of entrance hallway with staircase leading to the first floor, lounge diner, modern fitted kitchen, first floor landing, three bedrooms (two double, one single), three piece family bathroom and fixed staircase leading to the attic room which makes an ideal fourth bedroom or office. Externally the property offer driveway parking and sits on a good sized corner plot which offers further ENTRANCE HALL LOUNGE/DINER development potential in the form of a side extension 11' 5" x 5' 10" (3.48m x 1.79m) 21' 5" x 10' 0" (6.53m x 3.07m) (subject to planning), lawned gardens to the front and Front facing entrance door, radiator, fitted storage (width reducing to 2.55m) Front & rear facing double side, paved rear garden, wooden garden shed and plus under stair storage cupboard with power and glazed windows, two radiators, ceiling coves, neutral walled, fenced and hedged boundaries. -

Rochdale Village and the Rise and Fall of Integrated Housing in New York City by Peter Eisenstadt

Rochdale Village and the rise and fall of integrated housing in New York City by Peter Eisenstadt When Rochdale Village opened in southeastern Queens in late 1963, it was the largest housing cooperative in the world. When fully occupied its 5,860 apartments contained about 25,000 residents. Rochdale Village was a limited-equity, middle-income cooperative. Its apartments could not be resold for a profit, and with the average per room charges when opened of $21 a month, it was on the low end of the middle-income spectrum. (3) It was laid out as a massive 170 acre superblock development, with no through streets, and only winding pedestrian paths, lined with newly planted trees, crossing a greensward connecting the twenty massive cruciform apartment buildings. Rochdale was a typical urban post-war housing development, in outward appearance differing from most others simply in its size. It was, in a word, wrote historian Joshua Freeman, "nondescript." (4) Appearances deceive. Rochdale Village was unique; the largest experiment in integrated housing in New York City in the 1960s, and very likely the largest such experiment anywhere in the United States (5). It was located in South Jamaica, which by the early 1960s was the third largest black neighborhood in the city. Blacks started to move to South Jamaica in large numbers after World War I, and by 1960 its population was almost entirely African American. It was a neighborhood of considerable income diversity, with the largest tracts of black owned private housing in the city adjacent to some desperate pockets of poverty. -

Crompton Moor Crompton Moor Crompton Moor Covers About 160 Acres and Offers a Walking Is Good for You Because It Can: Wide Variety of Walking Experiences

Welcome to History Walking Crompton Moor Crompton Moor Crompton Moor covers about 160 acres and offers a Walking is good for you because it can: wide variety of walking experiences. Despite its natural Make you feel good Let’s go for a This leaflet is one of a series appearance the site has quite an industrial past with the mining of sandstone and coal once an important Give you more energy that describes some easy factor in the life of the moor. Brushes Clough Reservoir Reduce stress and help you sleep better walks around some of was constructed in the 19th century with stone from the quarries. Keep your heart ‘strong’ and reduce Oldham’s fantastic parks blood pressure Woodland planting in the 1970s considerably changed and countryside areas. the appearance of the area and many of the paths Help to manage your weight walk now skirt the woodland, although they are always They are designed to show The current recommendation for physical activity is just worth exploring. you routes that can be 30 minutes a day of moderate activity, such as brisk followed until you get to The moor is used by many groups including walking. That’s all it takes to feel the difference. You don’t cyclists and horse riders and recent developments have to do them all in one go to start with, you could walk know the areas and can seek to encourage greater use of the site by the for ten minutes, three times a day or 15 minutes twice explore some of the other local community. -

Popular Political Oratory and Itinerant Lecturing in Yorkshire and the North East in the Age of Chartism, 1837-60 Janette Lisa M

Popular political oratory and itinerant lecturing in Yorkshire and the North East in the age of Chartism, 1837-60 Janette Lisa Martin This thesis is submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of York Department of History January 2010 ABSTRACT Itinerant lecturers declaiming upon free trade, Chartism, temperance, or anti- slavery could be heard in market places and halls across the country during the years 1837- 60. The power of the spoken word was such that all major pressure groups employed lecturers and sent them on extensive tours. Print historians tend to overplay the importance of newspapers and tracts in disseminating political ideas and forming public opinion. This thesis demonstrates the importance of older, traditional forms of communication. Inert printed pages were no match for charismatic oratory. Combining personal magnetism, drama and immediacy, the itinerant lecturer was the most effective medium through which to reach those with limited access to books, newspapers or national political culture. Orators crucially united their dispersed audiences in national struggles for reform, fomenting discussion and coalescing political opinion, while railways, the telegraph and expanding press reportage allowed speakers and their arguments to circulate rapidly. Understanding of political oratory and public meetings has been skewed by over- emphasis upon the hustings and high-profile politicians. This has generated two misconceptions: that political meetings were generally rowdy and that a golden age of political oratory was secured only through Gladstone’s legendary stumping tours. However, this thesis argues that, far from being disorderly, public meetings were carefully regulated and controlled offering disenfranchised males a genuine democratic space for political discussion.