Biorock Electric Reefs Grow Back Severely Eroded Beaches in Months

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

U.S. House of Representatives Committee on Natural Resources

U.S. House of Representatives Committee on Natural Resources Subcommittee on Public Lands and Environmental Regulation Increasing Carbon Soil Sequestration on Public Lands Expert Testimony by Dr. W. Richard Teague Texas A&M AgriLife Research Wednesday, June 25, 2014 Good afternoon. Thank you Chairman Bishop, Ranking Member Grijalva, and all of the members of this subcommittee for the chance to speak with you today. I am Richard Teague, Associate Resident Director of Texas A&M AgriLife Research in Vernon, Texas. I am also a Professor in the Department of Ecosystem Science and Management at Texas A&M University and Senior Scientist of the Texas A&M Norman Borlaug Institute for International Agriculture. I am honored to speak with you today about the important issue of increasing carbon sequestration on public lands. Background and experience I was raised in a farm community and schooled in Zimbabwe before obtaining a BSc (Agriculture) in grassland science (1972) at Natal University in Pietermaritzburg, South Africa, and a PhD in botany and microbiology (1987) at the University of the Witwatersrand in Johannesburg, South Africa. As a research scientist working on the management of rangelands since 1972, I have visited most grazing areas of the world, attending conferences and presenting the results of my research. I actively seek out leading conservation ranchers in the ecoregions I visit, including Zimbabwe, South Africa, Namibia, Australia, New Zealand, Argentina, Chile, Canada and most of the western rangeland states in USA. I am intimately aware of the research that has been done on grazing management in most parts of the world. -

Powering the Blue Economy: Exploring Opportunities for Marine Renewable Energy in Martime Markets

™ Exploring Opportunities for Marine Renewable Energy in Maritime Markets April 2019 This report is being disseminated by the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE). As such, this document was prepared in compliance with Section 515 of the Treasury and General Government Appropriations Act for fiscal year 2001 (Public Law 106-554) and information quality guidelines issued by DOE. Though this report does not constitute “influential” information, as that term is defined in DOE’s information quality guidelines or the Office of Management and Budget’s Information Quality Bulletin for Peer Review, the study was reviewed both internally and externally prior to publication. For purposes of external review, the study benefited from the advice and comments of nine energy industry stakeholders, U.S. Government employees, and national laboratory staff. NOTICE This report was prepared as an account of work sponsored by an agency of the United States government. Neither the United States government nor any agency thereof, nor any of their employees, makes any warranty, express or implied, or assumes any legal liability or responsibility for the accuracy, completeness, or usefulness of any information, apparatus, product, or process disclosed, or represents that its use would not infringe privately owned rights. Reference herein to any specific commercial product, process, or service by trade name, trademark, manufacturer, or otherwise does not necessarily constitute or imply its endorsement, recommendation, or favoring by the United States government or any agency thereof. The views and opinions of authors expressed herein do not necessarily state or reflect those of the United States government or any agency thereof. -

Annual Reports 2014

INDEX Message from the Director-General 1 Research Activities 3 Full Research 5 Incubation Studies 80 Completed Research (CR) Follow-up Grants 81 Centers for Research Development (CRD) and Promotion (CRP) 83 Outreach Program and Events RIHN International Symposium 84 RIHN Forum 85 RIHN Public Seminars 86 RIHN Kids Seminar 86 RIHN Open House 86 RIHN Area Seminars 86 RIHN Tokyo Seminar 87 The Earth Forum Kyoto and International Symposium 87 The Earth Hall of Fame KYOTO 87 RIHN Seminars 87 Lunch Seminars (Danwakai) 88 RIHN Annual Open Meeting 90 Press Conferences 90 Publications 91 Individual Achievements 92 Appendices 1. Number and Affiliation of Project Members 2. Research Fields of Project Members 3. Research Project Sites 1 Message from the Director-General The Research Institute for Humanity and Nature was established in April 2001 by the Government of Japan to promote integrated research in the field of global environmental studies. As a national institute, RIHN solicits, develops, hosts, and funds fixed-term research projects on pressing areas of interaction between humanity and nature. RIHN thus promotes coordinated, problem-centered, context-specific, and multi-dimensional science. RIHN projects can last from three to five years; they are always multidisciplinary and employ multiple methodologies, and they are supposed to offer solutions to the problems under through trans-disciplinary approach with various stakeholders of the society. As of the end of FY2014 RIHN has completed twenty-six research projects, each of which has established extensive research networks in order to make important contributions in its area of specialization. FY2014 is the final year of the phase II of the interim plan of RIHN, and we overviewed the overall activities of the institute and published the report of the external review. -

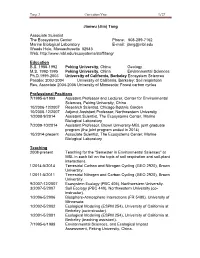

Jianwu (Jim) Tang Associate Scientist The

Tang, J. Curriculum Vitae 1/27 Jianwu (Jim) Tang Associate Scientist The Ecosystems Center Phone: 508-289-7162 Marine Biological Laboratory E-mail: [email protected] Woods Hole, Massachusetts 02543 Web: http://www.mbl.edu/ecosystems/staff/tang/ Education B.S. 1988-1992 Peking University, China Geology M.S. 1992-1995 Peking University, China Environmental Sciences Ph.D.1999-2003 University of California, Berkeley Ecosystem Sciences Postdoc 2003-2004 University of California, Berkeley: Soil respiration Res. Associate 2004-2006 University of Minnesota: Forest carbon cycles Professional Positions 7/1995-6/1999 Assistant Professor and Lecturer, Center for Environmental Sciences, Peking University, China 10/2006-12/2007 Research Scientist, Chicago Botanic Garden 10/2006-12/2007 Adjunct Assistant Professor, Northwestern University 1/2008-9/2014 Assistant Scientist, The Ecosystems Center, Marine Biological Laboratory 7/2009-10/2014 Assistant Professor, Brown University-MBL joint graduate program (the joint program ended in 2014) 10/2014-present Associate Scientist, The Ecosystems Center, Marine Biological Laboratory Teaching 2008-present Teaching for the “Semester in Environmental Sciences” at MBL in each fall on the topic of soil respiration and soil-plant interactions. 1/2014-5/2014 Terrestrial Carbon and Nitrogen Cycling (GEO 2920), Brown University. 1/2011-5/2011 Terrestrial Nitrogen and Carbon Cycling (GEO 2920), Brown University. 9/2007-12/2007 Ecosystem Ecology (PBC 405), Northwestern University. 3/2007-5/2007 Soil Ecology (PBC 440), Northwestern University (co- instructor). 1/2006-5/2006 Biosphere-Atmosphere Interactions (FR 5480), University of Minnesota. 1/2002-5/2002 Ecological Modeling (ESPM 254), University of California at Berkeley (co-instructor). -

The Biorock Process, Picturing Reef

hinter dem Front cover jpg. liegt die original Datei! The Biorock Process Picturing reef building with electricity by Ari Spenhoff Global Coral Reef Alliance / Sun & Sea e.V. For more information please check: last updated: April 2010 www.globalcoral.org The author is a member of: Global Coral Reef Alliance and Sun & Sea e.V. mail: [email protected] CONTENTS www.globalcoral.org Coral reefs are Sun & Sea e.V. Action needed Sun & Sea's objective is to promote science and arts in the field of mineral Coral rescue accretion (Biorock® Process) on an international level, and exclusively pursues interests of public-benefit. The Artificial reefs organization is based in Hamburg, Germany and operating under non-profit status. Reef therapy Curative approach Crutches for reefs Seascape design Reef construction Placing a new reef Electric reefs Jump-starting a reef Fishhunters to fishfarmers Shore protection Tourism and reefs Global Coral Reef Alliance (GCRA) Reefs and responsibility GCRA is a non-profit, 501 (c) 3 corporation based in Cambridge Awards and recognition Massachusetts, USA. It is a world-wide coalition The Biorock group of scientists, divers, environmentalists and other individuals and organizations, committed to coral reef preservation. Primary focus is on coral reef restoration, marine diseases and other issues caused by global climate change, environmental stress and pollution. Coral reefs are... Latest coral reef assessments Another explanation might be Action needed (2009) estimate that 25 percent of reduced solar activity as the the world's coral reefs are dead. A radiation of the sun is currently at a “Coral reefs face many large fraction has been killed by minimum, as evidenced by the threats. -

The Case Against Climate Geoengineering Acknowledgements

The Case Against Climate Geoengineering Acknowledgements Biofuelwatch, Heinrich Böll Foundation and ETC Group are grateful to all that collaborated in writing and reviewing this report. We would like to give special thanks to Lili Fuhr, Linda Schneider, Anja Chalmin, Holly Dressel, Joana Chelo, Oliver Munnion and Simon Fischer for research and writing support. We also gratefully acknowledge the financial support from the Heinrich Böll Foundation, the CS Fund and the Rockerfeller Brothers Fund to produce this report. Biofuelwatch, Heinrich Böll Foundation and ETC Group are solely responsible for the views expressed in this report. The original research for this report was done by the ETC Group and Biofuelwatch, with the financial support and collaboration of the Heinrich Böll Foundation. Editing by Kathy Jo Wetter and Trudi Zundel Design by Stig First published November 2017 All our publications are downloadable free of charge at: www.biofuelwatch.org.uk www.boell.de www.etcgroup.org Published under the Creative Commons licence: Attribution – Non-Commercial – No Derivatives 3.0 BIGTHE BAD FIX The Case Against Climate Geoengineering www.etcgroup.org www.biofuelwatch.org www.boell.de/en Contents 5 Chapter 1 – Geoengineering: The Emperors’ New Climate A New, Environmental Empire; Empire’s Techno-fixes 6 Does the Emperor have Clothes? Empirical Hubris in History 7 A “Climate of the Willing”? 8 The Emperor’s new hose? 10 Safe, fair and ecologically sustainable solutions to the climate crisis 11 Chapter 2 – Geoengineering: The Technologies 12 -

Ll~~D G-~,T,'T~ M Lb Oao~ SR

~ \Ll~~D G-~,t,'t~ M lb Oao~ SR.. \ C\ Cf \ ACTIVATING GEOTHERAPY AND GLOBAL BIOETHICS 1. Creating a global bioethics. Transforming the Earth into a stable and unpolluted ecosystem will depend on the will of its peoples. The will must be nurtured by accurate information about the state of the planet and possibilities for the betterment and survival of the Biosphere, which is presently disturbed by human numbers and lifestyles. Possibilities of improving the biosphere correspond to "geotherapy", care of the Earth. Improving the health of the biosphere (including humanity) requires a conscious programme of geotherapy. Like medical therapy, geotherapy should use the latest scientific information, experience and common sense to diagnose patient Earth's ills, prescribe a corrective regime and apply it in a disciplined manner, without exaggeration, to establish vigorous health. Geotherapeutic measures must be motivated, that is they must be acceptable to and desired by all peoples. The principles of global bioethics should serve as a guide for geotherapy, our future cultural evolution and the biological evolution of other species, which we ineluctably control. Global bioethics is not an existing system for export from industrialized countries; it should be a common synthesis of all countries. It includes accepting responsibility for delivering an improved world to our descendants. Its immediate task is to identify a human consensus on desires and will for the future. The rational base for global bioethics should come from a scientific understanding of the Earth, its history, processes and inhabitants. To go with this understanding a global philosophy for bettering life is essential to the well-being and survival of our species and others. -

The United Nations Decade on Ecosystem Restoration Strategy

The United Nations Decade on Ecosystem Restoration Strategy Table of Contents 1. Introduction a) Restoration, conservation and sustainable use of natural resources b) Role of the UN Member States 2. Vision and theory of change a) Barriers b) Pathways 3. Implementation a) Pathway I: building a global movement · Facilitating collaboration · Developing a values-based restoration imperative · Engaging individuals · Partnering with youth · Working with educators · Showcasing flagships and champions · Laying post-2030 foundations b) Pathway II: generating political support · Engaging heads of state and other decision-makers · Convening cross-sectoral dialogues · Unlocking and reorienting finance c) Pathway III: building technical capacity · Deploying science and technology in ecosystem restoration · Catalysing and accelerating action on the ground d) Management arrangements · Governance structures · Funding · Monitoring progress i Executive Summary: The UN Decade on Ecosystem Restoration This strategy is the result of a global, open and inclusive consultation process in 2019 and 2020. It will be adapted periodically and will guide the implementation of the UN Decade by all stakeholders in a spirit of partnership, inclusiveness and joint coordinated action. The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development seeks to end poverty, conserve biodiversity, combat climate change and improve livelihoods for everyone, everywhere. These objectives, encapsulated in 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) are unlikely to be met unless ecosystem degradation is stopped and ecosystem restoration is undertaken at the immense scale of hundreds of millions of hectares globally. Currently, there is insufficient political support and technical capacity in both the public and private sectors to invest in the many hundreds of thousands of ecosystem restoration initiatives worldwide that are needed to achieve restoration at such a scale. -

Sustainable Building Materials Grown in Seawater

THE FUTURE IS HERE: ACHIEVING UNIVERSAL ACCESS AND CLIMATE TARGETS Manila 5-8 June, 2017 Sustainable Building Materials Grown in Seawater Scott Countryman, Executive Director, The Coral Triangle Conservancy, (dba Reeph) • Acknowledgements to Dan Millison, Transcendergy, LLC and Dr. Thomas Goreau President, Biorock Technology Inc. • 70 countries and territories have “million dollar reefs”, or reefs that generate approximately $1 million per square kilometer • These reefs are generating jobs, and critical foreign exchange earnings for many small island states that have few alternative sources of employment and income. • 4,000 dive centers, 15,000 dive sites and 125,000 hotels were used to further assess the proportion of tourism spending that can be attributed to coral reefs. • Coral reefs can yield an average 15 tonnes of fish and other seafood per square kilometer per year. • And yet, nearly 60 percent of the world's coral reefs are threatened by human activity. In places like the Philippines only 1% are in excellent condition and the dual threat of climate change and ocean acidification threaten to wipe up all coral reefs within the next 35 years. ‘WHAT WE DO IN THE NEXT 10 YEARS WILL DETERMINE THE FATE OF OUR OCEANS FOR THE NEXT 10,000 YEARS’ -Sylvia Earl Mission and Objectives of Venture The Coral Triangle Conservancy Is a not for profit philanthropic venture based in the Philippines campaigning to establish networks of ecosystem sized marine protected areas while pioneering new technologies and social programs to end overfishing. Our programs seek to increase awareness of the importance of coral reefs and then seed and incubate locally managed businesses that create economic incentives for conservation activities. -

Miller S Mmmgraduateproject.Pdf (5.097Mb)

Electrically stimulated artificial mussel (Mytilus edulis) reefs to create shoreline protection and coastal habitat in St. Margaret’s Bay, Nova Scotia. Authored By Stefan Miller Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Of Master of Marine Management At Dalhousie University Halifax, Nova Scotia November 2020 © Stefan Miller, 2020 Table of Contents List of Tables..................................................................................................................................4 List of Figures................................................................................................................................4 Abstract..........................................................................................................................................6 Chapter 1: Climate Context ........................................................................................................7 Chapter 2: Coastal Impacts .........................................................................................................8 Chapter 3: Hard and Soft Solutions ..........................................................................................11 Chapter 4: One Potential Defensive Solution ...........................................................................13 4.1: The Invention of Biorock™........................................................................................13 4.2: Potential Impacts of the Technology .........................................................................16 -

Reef Restoration As a Fisheries Management Tool - Thomas J

FISHERIES AND AQUACULTURE – Vol. V – Reef Restoration As a Fisheries Management Tool - Thomas J. Goreau and Wolf Hilbertz REEF RESTORATION AS A FISHERIES MANAGEMENT TOOL Thomas J. Goreau and Wolf Hilbertz Global Coral Reef Alliance, Cambridge, MA, USA Keywords: Coral, reef, fisheries, habitat, standing stocks, carrying capacity, overharvesting, degradation, restoration. Contents 1. Introduction: coral reef fisheries 2. Coral reef fisheries decline 3. Causes of decline: Overfishing 4. Causes of decline: Habitat Degradation 5. Marine Protected Areas in reef fisheries management 5.1. The Marine Protected Area Strategy 5.2 Top Down and Bottom Up Management Strategies 5.3. Global Change and Marine Protected Areas 6. Natural reef regeneration 7. Restoration methods 7.1. Stress Abatement 7.2. Artisanal Restoration. 7.3. Artificial Reefs 7.4. Coral Growth on Exotic Materials 8. Electrical reef restoration 8.1 A Promising New Coral Reef Restoration Method 8.2. Coral Recruitment 8.3. Fish and Invertebrate Recruitment 8.4. Mariculture 8.5. Shore Protection 9. Conclusions Glossary Bibliography Biographical Sketches Summary UNESCO – EOLSS Coral reef fisheries feed nearly a billion people, almost all in poor tropical countries. Conventional strategiesSAMPLE of coral reef conservation CHAPTERS and fisheries management focus on controlling fishing within limited “protected” areas, but generally ignore habitat quality or global changes, which are increasingly rendering the methods of the past obsolete and ineffectual. Yet the precipitous ongoing decline of coral reef fisheries stems from habitat degradation as well as over-fishing and cannot be reversed without restoring habitat quality in damaged areas. Reef habitat degradation is largely caused by external stresses like high temperature, new diseases, and land-derived pollution, which kill corals, reduce biodiversity of food supplies for harvested species, and are beyond the capacity of any marine protected area (MPA) to control. -

The Effect of Biorock Coral Reef Restoration on Tourist Travel

THE EFFECT OF BIOROCK CORAL REEF RESTORATION ON TOURIST TRAVEL DECISIONS AT PEMUTERAN BAY, BALI ! Beta Budisetyorini Head of Tourism Faculty Tourism Destination Program, Faculty of Tourism, Bandung Institute of Tourism Jalan Dr. Setiabudhi 186 Bandung, West Java, Indonesia [email protected]! Shassy Endah Cahyani Lecturer Assistant Tourism Destination Program, Faculty of Tourism, Bandung Institute of Tourism Jalan Dr. Setiabudhi 186 Bandung, West Java, Indonesia [email protected] ABSTRACT Coral reef degradation has been a major environmental issue in the world. Coral reef ecosystems are fragile to threats, especially from climate change and anthropogenic activities such as fisheries and tourism. In 1998, coral reefs in Pemuteran Bay were devastated by El Niño phenomenon and destructive fishing practices that caused by economic crisis. The degradation triggered Pemuteran Bay to start coral reef restoration with Biorock technology. The Biorock coral reef restoration succeeded to increase the ecosystem quality, which attracts tourist to visit Pemuteran Bay. This paper presents an analysis of the influence given by Biorock coral reef towards tourist travel decisions to Pemuteran Bay. The result of multiple regression analysis indicates Biorock coral reef has a significant effect towards travel decision. The effect is equal to 70,4% and the residual is equal to 29,6%. Implication of the result indicates Biorock coral reef restoration is applicable in another coastal area to increase coral reefs ecosystem quality. Moreover, it will provide valuable and vital ecosystem services, which also can gives economic benefits through marine ecotourism Keywords: Biorock, coral reefs ecosystem, travel decision, marine ecotourism ! 1! INTRODUCTION Coral reefs worldwide are significant sources for global ecosystem health and in economic value (Wielgus et al, 2003).