Bloodsucking Conenose)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vectors of Chagas Disease, and Implications for Human Health1

ZOBODAT - www.zobodat.at Zoologisch-Botanische Datenbank/Zoological-Botanical Database Digitale Literatur/Digital Literature Zeitschrift/Journal: Denisia Jahr/Year: 2006 Band/Volume: 0019 Autor(en)/Author(s): Jurberg Jose, Galvao Cleber Artikel/Article: Biology, ecology, and systematics of Triatominae (Heteroptera, Reduviidae), vectors of Chagas disease, and implications for human health 1095-1116 © Biologiezentrum Linz/Austria; download unter www.biologiezentrum.at Biology, ecology, and systematics of Triatominae (Heteroptera, Reduviidae), vectors of Chagas disease, and implications for human health1 J. JURBERG & C. GALVÃO Abstract: The members of the subfamily Triatominae (Heteroptera, Reduviidae) are vectors of Try- panosoma cruzi (CHAGAS 1909), the causative agent of Chagas disease or American trypanosomiasis. As important vectors, triatomine bugs have attracted ongoing attention, and, thus, various aspects of their systematics, biology, ecology, biogeography, and evolution have been studied for decades. In the present paper the authors summarize the current knowledge on the biology, ecology, and systematics of these vectors and discuss the implications for human health. Key words: Chagas disease, Hemiptera, Triatominae, Trypanosoma cruzi, vectors. Historical background (DARWIN 1871; LENT & WYGODZINSKY 1979). The first triatomine bug species was de- scribed scientifically by Carl DE GEER American trypanosomiasis or Chagas (1773), (Fig. 1), but according to LENT & disease was discovered in 1909 under curi- WYGODZINSKY (1979), the first report on as- ous circumstances. In 1907, the Brazilian pects and habits dated back to 1590, by physician Carlos Ribeiro Justiniano das Reginaldo de Lizárraga. While travelling to Chagas (1879-1934) was sent by Oswaldo inspect convents in Peru and Chile, this Cruz to Lassance, a small village in the state priest noticed the presence of large of Minas Gerais, Brazil, to conduct an anti- hematophagous insects that attacked at malaria campaign in the region where a rail- night. -

Ontogeny, Species Identity, and Environment Dominate Microbiome Dynamics in Wild Populations of Kissing Bugs (Triatominae) Joel J

Brown et al. Microbiome (2020) 8:146 https://doi.org/10.1186/s40168-020-00921-x RESEARCH Open Access Ontogeny, species identity, and environment dominate microbiome dynamics in wild populations of kissing bugs (Triatominae) Joel J. Brown1,2†, Sonia M. Rodríguez-Ruano1†, Anbu Poosakkannu1, Giampiero Batani1, Justin O. Schmidt3, Walter Roachell4, Jan Zima Jr1, Václav Hypša1 and Eva Nováková1,5* Abstract Background: Kissing bugs (Triatominae) are blood-feeding insects best known as the vectors of Trypanosoma cruzi, the causative agent of Chagas’ disease. Considering the high epidemiological relevance of these vectors, their biology and bacterial symbiosis remains surprisingly understudied. While previous investigations revealed generally low individual complexity but high among-individual variability of the triatomine microbiomes, any consistent microbiome determinants have not yet been identified across multiple Triatominae species. Methods: To obtain a more comprehensive view of triatomine microbiomes, we investigated the host-microbiome relationship of five Triatoma species sampled from white-throated woodrat (Neotoma albigula) nests in multiple locations across the USA. We applied optimised 16S rRNA gene metabarcoding with a novel 18S rRNA gene blocking primer to a set of 170 T. cruzi-negative individuals across all six instars. Results: Triatomine gut microbiome composition is strongly influenced by three principal factors: ontogeny, species identity, and the environment. The microbiomes are characterised by significant loss in bacterial diversity throughout ontogenetic development. First instars possess the highest bacterial diversity while adult microbiomes are routinely dominated by a single taxon. Primarily, the bacterial genus Dietzia dominates late-stage nymphs and adults of T. rubida, T. protracta, and T. lecticularia but is not present in the phylogenetically more distant T. -

Bioenvironmental Correlates of Chagas´ Disease- S.I Curto

MEDICAL SCIENCES - Vol.I - Bioenvironmental Correlates of Chagas´ Disease- S.I Curto BIOENVIRONMENTAL CORRELATES OF CHAGAS´ DISEASE S.I Curto National Council for Scientific and Technological Research, Institute of Epidemiological Research, National Academy of Medicine – Buenos Aires. Argentina. Keywords: Chagas´ Disease, disease environmental factors, ecology of disease, American Trypanosomiasis. Contents 1. Introduction 2. Biological members and transmission dynamics of disease 3. Interconnection of wild, peridomestic and domestic cycles 4. Dynamics of domiciliation of the vectors: origin and diffusion of the disease 5. The rural housing as environmental problem 6. Bioclimatic factors of Triatominae species 7. Description of disease 8. Rates of human infection 9. Conclusions Summary Chagas´ disease is intimately related to sub development conditions of vast zones of Latin America. For that reason we must approach this problem through a transdisciplinary and totalized perspective. In that way we analyze the dynamics of different transmission cycles: wild, yard, domiciled, rural and also urban. The passage from a cycle to another constitutes a domiciliation dynamics even present that takes from hundred to thousands of years and that even continues in the measure that man destroys the natural ecosystems and eliminates the wild habitats where the parasite, the vectors and the guests take refuge. Also are analyzed the main physical factors that influence the persistence of the illness and their vectors as well as the peculiarities of the rural house of Latin America that facilitate the coexistence in time and man's space, the parasites and the vectors . Current Chagas’UNESCO disease transmission is –relate EOLSSd to human behavior, traditional, cultural and social conditions SAMPLE CHAPTERS 1. -

Kissing Bug” — Delaware, 2018 the United States, but Only a Few Cases of Chagas Disease from Paula Eggers1; Tabatha N

Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report Notes from the Field Identification of a Triatoma sanguisuga Chagas disease is found. Triatomine bugs also are found in “Kissing Bug” — Delaware, 2018 the United States, but only a few cases of Chagas disease from Paula Eggers1; Tabatha N. Offutt-Powell1; Karen Lopez2; contact with the bugs have been documented in this country Susan P. Montgomery3; Gena G. Lawrence3 (2). Although presence of the vector has been confirmed in Delaware, there is no current evidence of T. cruzi in the state In July 2018, a family from Kent County, Delaware con- (2). T. cruzi is a zoonotic parasite that infects many mammal tacted the Delaware Division of Public Health (DPH) and species and is found throughout the southern half of the United the Delaware Department of Agriculture (DDA) to request States (2). Even where T. cruzi is circulating, not all triatomine assistance identifying an insect that had bitten their child’s face bugs are infected with the parasite. The likelihood of human while she was watching television in her bedroom during the T. cruzi infection from contact with a triatomine bug in the late evening hours. The parents were concerned about possible United States is low, even when the bug is infected (2). disease transmission from the insect. Upon investigation, DPH Precautions to prevent house triatomine bug infestation learned that the family resided in an older single-family home include locating outdoor lights away from dwellings such as near a heavily wooded area. A window air conditioning unit homes, dog kennels, and chicken coops and turning off lights was located in the bedroom where the bite occurred. -

Kissing Bugs: Not So Romantic

W 957 Kissing Bugs: Not So Romantic E. Hessock, Undergraduate Student, Animal Science Major R. T. Trout Fryxell, Associate Professor, Department of Entomology and Plant Pathology K. Vail, Professor and Extension Specialist, Department of Entomology and Plant Pathology What Are Kissing Bugs? Pest Management Tactics Kissing bugs (Triatominae), also known as cone-nosed The main goal of kissing bug management is to disrupt bugs, are commonly found in Central and South America, environments that the insects will typically inhabit. and Mexico, and less frequently seen in the southern • Focus management on areas such as your house, United States. housing for animals, or piles of debris. These insects are called “kissing bugs” because they • Fix any cracks, holes or damage to your home’s typically bite hosts around the eyes and mouths. exterior. Window screens should be free of holes to Kissing bugs are nocturnal blood feeders; thus, people prevent insect entry. experience bites while they are sleeping. Bites are • Avoid placing piles of leaves, wood or rocks within 20 usually clustered on the face and appear like other bug feet of your home to reduce possible shelter for the bites, as swollen, itchy bumps. In some cases, people insect near your home. may experience a severe allergic reaction and possibly • Use yellow lights to minimize insect attraction to anaphylaxis (a drop in blood pressure and constriction the home. of airways causing breathing difculty, nausea, vomiting, • Control or minimize wildlife hosts around a property to skin rash, and/or a weak pulse). reduce additional food sources. Kissing bugs are not specifc to one host and can feed • See UT Extension publications W 658 A Quick on a variety of animals, such as dogs, rodents, reptiles, Reference Guide to Pesticides for Pest Management livestock and birds. -

Identification of Bloodmeal Sources And

Identification of bloodmeal sources and Trypanosoma cruzi infection in triatomine bugs (Hemiptera: Reduviidae) from residential settings in Texas, the United States Sonia A. Kjos, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Paula L. Marcet, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Michael J. Yabsley, University of Georgia Uriel Kitron, Emory University Karen F. Snowden, Texas A&M University Kathleen S. Logan, Texas A&M University John C. Barnes, Southwest Texas Veterinary Medical Center Ellen M. Dotson, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Journal Title: Journal of Medical Entomology Volume: Volume 50, Number 5 Publisher: Oxford University Press (OUP): Policy B - Oxford Open Option D | 2013-09-01, Pages 1126-1139 Type of Work: Article | Post-print: After Peer Review Publisher DOI: 10.1603/ME12242 Permanent URL: https://pid.emory.edu/ark:/25593/v72sq Final published version: http://dx.doi.org/10.1603/ME12242 Copyright information: © 2013 Entomological Society of America. Accessed September 30, 2021 9:56 PM EDT NIH Public Access Author Manuscript J Med Entomol. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2014 May 01. NIH-PA Author ManuscriptPublished NIH-PA Author Manuscript in final edited NIH-PA Author Manuscript form as: J Med Entomol. 2013 September ; 50(5): 1126–1139. Identification of Bloodmeal Sources and Trypanosoma cruzi Infection in Triatomine Bugs (Hemiptera: Reduviidae) From Residential Settings in Texas, the United States SONIA A. KJOS1,2,3, PAULA L. MARCET1, MICHAEL J. YABSLEY4,5, URIEL KITRON6, KAREN F. SNOWDEN7, KATHLEEN S. LOGAN7, JOHN C. BARNES8, and ELLEN M. DOTSON1 1 Division of Parasitic Diseases and Malaria, Entomology Branch, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 1600 Clifton Rd., MS G49, Atlanta, GA 30329. -

Triatoma Sanguisuga, Eastern Blood-Sucking Conenose Bug (Hemiptera: Reduviidae) Chris Carlton, Forest Huval and T.E

Triatoma sanguisuga, Eastern Blood-Sucking Conenose Bug (Hemiptera: Reduviidae) Chris Carlton, Forest Huval and T.E. Reagan Description a professional insect diagnostician. At least nine members Adults of the eastern blood-sucking conenose bug of the subfamily Triatominae occur in the U.S., most in the are relatively large insects three-quarters of an inch to genus Triatoma, with additional species in Central and South seven-eighths of an inch (18 to 22 mm) in body length. America. The eastern blood-sucking conenose bug, Triatoma The body shape and coloration of adults are distinctive. sanguisuga, is the most commonly encountered species The elongated head narrows toward the front and is in Louisiana, but it is not the only species that occurs in black with slender, six-segmented antennae and a sharp, the state. Of 130 Louisiana specimens in the Louisiana three-segmented beak that folds beneath the head when State Arthropod Museum, 126 are T. sanguisuga, three are the insect is not feeding. The triangular thorax is black Triatoma lecticularia and one is Triatoma gerstaekeri. These with a narrow orange insects are often referred to as “kissing bugs,” a name that is or pinkish-orange used for the entire family Triatominae. margin and a prominent, triangular black Life Cycle scutellum between The eastern conenose and other kissing bugs are the wing bases. The typically associated with mammal burrows, nests or forewings are folded other harborages of small mammals. They require a flat across the abdomen blood meal during each stage of development, thus the when at rest, and each close association with mammals. -

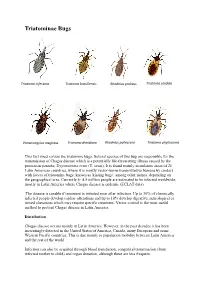

Triatominae Bugs

Triatominae Bugs Triatoma infestans Triatoma brasiliensis Rhodnius prolixus Triatoma sordida Panstrongylus megistus Triatoma dimidiata Rhodnius pallescens Triatoma phyllosoma This fact sheet covers the triatomine bugs. Several species of this bug are responsible for the transmission of Chagas disease which is a potentially life-threatening illness caused by the protozoan parasite, Trypanosoma cruzi (T. cruzi). It is found mainly in endemic areas of 21 Latin American countries, where it is mostly vector-borne transmitted to humans by contact with faeces of triatomine bugs, known as 'kissing bugs', among other names, depending on the geographical area. Currently 4- 4.5 million people are estimated to be infected worldwide, mostly in Latin America where Chagas disease is endemic (ECLAT data). The disease is curable if treatment is initiated soon after infection. Up to 30% of chronically infected people develop cardiac alterations and up to 10% develop digestive, neurological or mixed alterations which may require specific treatment. Vector control is the most useful method to prevent Chagas disease in Latin America. Distribution Chagas disease occurs mainly in Latin America. However, in the past decades it has been increasingly detected in the United States of America, Canada, many European and some Western Pacific countries. This is due mainly to population mobility between Latin America and the rest of the world. Infection can also be acquired through blood transfusion, congenital transmission (from infected mother to child) and organ donation, although these are less frequent. Transmission In Latin America, T. cruzi parasites are mainly transmitted by contact with the faeces of infected blood-sucking triatomine bugs. These bugs, vectors that carry the parasites, typically live in the cracks of poorly-constructed homes in rural or suburban areas. -

The Incidence of Trypanosoma Cruzi in Triatoma of Tucson, Arizona*

Rev. Biol. Trop., 14(1): 3-12, 1966 The Incidence of Trypanosoma cruzi in Triatoma of Tucson, Arizona* by David E. Bice*'� (Received for publication December 1, 1965) Trypanosoma cruzi was first reported in the United States in 1916 by KOFOID and· McCu LLOCH (4). They found a flagellate in an assassin bug, Triatoma protracta, collected in San Diego, California. Since the authors failed to infect young white rats upon which infected bugs fed and because no trypanosomes were detected in the blood of wood rats from nests containing infected bugs, th� trypanosome was named Trypanosoma triatomae. Later, KOFOID and DONAT (3) established that T. triatomae is in reality T. cruzi. Infected bugs, other than from California, were next collected near Tucson, Arizona and were examined by KOFOID and WHITAKER (5). PAckcHANIAN (9) reported the first naturally infected bugs from Texas, andWOOD (23) reported on the infectedTriatama of New Mexico. Mammals and Triatama in the southeastern United States have also been found to harbor T. cruzi. Of 1,584 mammals examined in Georgia (1) 103 were positive. Mammals were found infected in northern Florida (6) and Maryland (13, 14) . The trypanosomes from- these mammals are antigenically and· mórphologically the ,ame as T. cruz; from South America (15). yAEGER (25) found infected Triatoma from areas in Louisiana where infected mammals had been collected. OLSEN et al. ,(8) . reported infected opossums and raccoons from east-central Alabaína as well as infected Triatoma from the same area. In 1955 the first natural case of Chagas' disease was reported in the United States byWOODY andWOODY (24). -

Short-Range Responses of the Kissing Bug Triatoma Rubida (Hemiptera: Reduviidae) to Carbon Dioxide, Moisture, and Artificial Light

insects Article Short-Range Responses of the Kissing Bug Triatoma rubida (Hemiptera: Reduviidae) to Carbon Dioxide, Moisture, and Artificial Light Andres Indacochea 1, Charlotte C. Gard 2, Immo A. Hansen 3, Jane Pierce 4 and Alvaro Romero 1,* 1 Department of Entomology, Plant Pathology and Weed Science, New Mexico State University, Las Cruces, NM 88003, USA; [email protected] 2 Department of Economics, Applied Statistics, and International Business, New Mexico State University, Las Cruces, NM 88003, USA; [email protected] 3 Department of Biology, New Mexico State University, Las Cruces, NM 88003, USA; [email protected] 4 Department of Entomology, Plant Pathology and Weed Science, New Mexico State University, Artesia, NM 88210, USA; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-575-646-5550 Academic Editors: Changlu Wang and Chow-Yang Lee Received: 20 June 2017; Accepted: 25 August 2017; Published: 29 August 2017 Abstract: The hematophagous bug Triatoma rubida is a species of kissing bug that has been marked as a potential vector for the transmission of Chagas disease in the Southern United States and Northern Mexico. However, information on the distribution of T. rubida in these areas is limited. Vector monitoring is crucial to assess disease risk, so effective trapping systems are required. Kissing bugs utilize extrinsic cues to guide host-seeking, aggregation, and dispersal behaviors. These cues have been recognized as high-value targets for exploitation by trapping systems. a modern video-tracking system was used with a four-port olfactometer system to quantitatively assess the behavioral response of T. rubida to cues of known significance. -

Trypanosoma Cruzi-Infected Triatoma Gerstaeckeri (Hemiptera: Reduviidae) from Nuevo León, México, and Pathogenicity of the Regional Strain Zinnia J

Molina-GarzaBiomédica 2015;35:372-8 ZJ, Mercado-Hernández R, Molina-Garza DP, Galaviz-Silva L Biomédica 2015;35:372-8 doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.7705/biomedica.v35i3.2589 ORIGINAL ARTICLE Trypanosoma cruzi-infected Triatoma gerstaeckeri (Hemiptera: Reduviidae) from Nuevo León, México, and pathogenicity of the regional strain Zinnia J. Molina-Garza, Roberto Mercado-Hernández, Daniel P. Molina-Garza, Lucio Galaviz-Silva Departamento de Zoología de Invertebrados, Facultad de Ciencias Biológicas, Universidad Autónoma de Nuevo León, Nuevo León, México Introduction: Four species of triatomines have been reported in Nuevo León, northeast (NE) México, but Triatoma gerstaeckeri has only been recorded from a peridomestic dwelling. Objectives: To assess the natural infection index (NII) of Trypanosoma cruzi in triatomines and the infestation index (II) of T. gerstaeckeri collected in a suburban locality, and to collect histopathological data to understand tissue tropism of the regional T. cruzi strain (strain NE) obtained from the vectors collected after an experimental inoculation in Mus musculus. Materials and methods: Triatomines were collected from 85 houses and peridomiciles in Allende, Nuevo León. Stool samples were obtained to determine the T. cruzi NII and were used in an experimental mice infection. Results: A total of 118 T. gerstaeckeri were captured, and 46 (adults and nymphs) were collected inside the same house (II=1.17%). Thirty-seven reduvids were infected with T. cruzi (NII=31.3%). Tissue tropism of the T. cruzi NE strain was progressive in skeletal muscle, myocardial, and adipose tissues and was characterized by the presence of intracellular amastigotes and destruction of cardiac myocells. Conclusions: The presence of naturally infected domiciliary vectors is an important risk factor for public health in the region considering that these vectors are the principal transmission mechanism of the parasite. -

Red Margined Kissing Bug”

The Kiss of Death: A Rare Case of Anaphylaxis to the Bite of the “Red Margined Kissing Bug” Caleb Anderson MD and Conrad Belnap MD Abstract the pronotum, as shown in Figure 1.1,5 These insects are usually Triatoma (kissing bugs), a predatory genus of blood-sucking insects which found in rural areas and feed on warm blooded mammals to belongs to the family Reduviidae, subfamily Triatominae, is a well-known include chickens, rodents, dogs, and humans. They are able to vector in the transmission of Trypanosoma cruzi, the causative agent in Chagas disease. However, it is less well appreciated that bites from these consume two to four times their body weight in blood a day, and insects can cause a range of symptoms varying from localized cutaneous typically feed at night. The term “kissing bug” is a consequence symptoms to a generalized anaphylactic reaction. While anaphylactic reactions of the insect’s predilection of biting the victim’s face because following bites have been reported with five of the eleven species endemic to it is often the most accessible body part.2 the United States, the majority are associated with Triatoma protracta, and Triatoma bites are associated with a variety of other adverse Triatoma rubida. There have been very few reported cases of anaphylactic reactions, which can range from mild localized inflammation reaction to the bite Triatoma rubrofasciata, which is endemic to Florida and to a severe, systemic, anaphylactic reaction. Allergic reactions Hawai‘i. We report a case of a 50 year old previously healthy female from a rural area in Honolulu County who suffered three separate bites from Triatoma following bites from five different Triatoma species have been rubrofasciata and experienced a generalized anaphylactic reaction on each reported.