Biographical Memoir Theodore Nicholas Gill 1837

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mark H. Dall Collection, 1574-1963

Mark H. Dall Collection, 1574-1963 by Smithsonian Institution Archives Smithsonian Institution Archives Washington, D.C. Contact us at [email protected] http://siarchives.si.edu Table of Contents Collection Overview......................................................................................................... 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Descriptive Entry.............................................................................................................. 1 Names and Subject Terms ............................................................................................. 1 Container Listing.............................................................................................................. 3 Mark H. Dall Collection Accession 87-057 Collection Overview Repository: Smithsonian Institution Archives, Washington, D.C., [email protected] Creator: Dall, Mark H Title: Mark H. Dall Collection Dates: 1574-1963 Quantity: 7.69 cu. ft. (7 record storage boxes) (1 16x20 box) Administrative Information Preferred Citation Smithsonian Institution Archives, Accession 87-057, Dall, Mark H, Mark H. Dall Collection Descriptive Entry This accession consists of information about the Healey family; the personal and business correspondence of Mark Healey, maternal grandfather to William Healey Dall; poetry, correspondence, publications, photographs, and sermons by and pertaining to Charles Henry Appleton Dall, first Unitarian minister in India, -

Dall's Porpoise

Dall’s Porpoise Phocoenoides dalli, commonly known as the Dall’s porpoise, is most easily recognized by its unique black and white markings similar to those of a killer whale/orca. It was named by the American naturalist William Healey Dall who was the first to collect a specimen. The Dall’s porpoise is capable of swimming in excess of 30 knots and is often seen riding along side the bows of boats. General description: The Dall’s porpoise is black with white markings. Most commonly the animal will be mostly black with large white sections on the sides, belly, on the edges of the flukes, and around the dorsal fin, though there are exceptions to this pattern. The Dall’s porpoise is born at an approximate size of 3ft. The average size of an adult is 6.4 ft and weighs approximately 300 lbs. The body is stocky and more powerful than other members of phocoenidae (porpoises). The head is small and lacks a distinct beak. The flippers are small, pointed, and located near the head. The dorsal fin is triangular in shape with a hooked tip. The mouth of the Dall’s porpoise is small and has a slight underbite. Food habits: Dall’s porpoises eat a wide variety of prey species. In some areas they eat squid, but in other areas they may feed on small schooling fishes such as capelin, lantern fish (Myctophids), and herring. They generally forage at night. Life history: Female Dall’s porpoises reach sexual maturity at between 3 and 6 years of age and males around 5 to 8 years, though there is little known about their mating habits. -

Tution in Washington, April 16, 17,And 18, 1917

390 REPORT OF THE ANNUAL MEETING REPORT OF THE ANNUAL MEETING Prepared by the Home Secretary The annual meeting of the Academy was held at the Smithsonian Insti- tution in Washington, April 16, 17, and 18, 1917. Seventy-three members were present as follows: Messrs. C. G. Abbot, Abel, Barnard, Becker, Bogert, Cannon, Cattell, Chittenden, W. B. Clark, F. W. Clarke, J. M. Clarke, Conklin, Coulter, Crew, Cross, Dall, Dana, Davenport, Davis, Day, Dewey, Donaldson, Fewkes, Flexner, Frost, Gom- berg, Hague, Hale, E. H. Hall, Harper, Hayford, Hillebrand, Holmes, Howard, Howell, Iddings, Jennings, Lillie, Loeb, Lusk, Mall, Meltzer, Merriam, Merritt, Michelson, Millikan, Moore, Morley, E. L. Nichols, E. F. Nichols, A. A. Noyes, W. A. Noyes, H. F. Osborn, Pearl, Pickering, Pupin, Ransome, Remsen, Rosa, Schlesinger, Scott, Erwin F. Smith, Stieg- litz, Van Vleck, Vaughan, Walcott, Webster, Welch, Wheeler, D. White, H. S. White, Wilson, R. W. Wood. BUSINESS SESSIONS The President announced the death since the Autumn Meeting of one for- eign Associate: GASTON DARBOUX. REPORTS FROM OFFICERS OF THE ACADEMY The annual report of the President to Congress for 1916 was presented and distributed. The President announced the appointment of the Local Committee as follows: CHARLES G. ABBOT, Chairman; WHITMAN CROSS, WILLIAM H. DALL, WILLAM F. HILLEBRAND, CHARLES D. WALCOTT. A Finance Committee for the PROCEEDINGS was also appointed, as follows: C. B. DAVENPORT, Chairman; M. T. BOGERT, W. B. CLARK, F. R. LILLTE, RAYMOND PEARL. Other committee appointments, with date of expiration were as follows: Program: C. G. ABBOT, Chairman, 1920; RAYMOND PEARL, 1920. Henry Draper Fund: A. -

William Healey Dall

SITE INDEX Home William Healey Dall 1845-1927 When he was in high The 1899 school, William Healey Expedition Dall fell in love -- with a book. The Report of the Invertebrata of Massachusetts , by A. A. Gould was hardly a romance, but the young Dall became immediately enchanted with mollusks: Original the conchs, clams, octopi Participants William Healey Dall. and their kind that make Source: Smithsonian up this class of sea Archives. creature. He eagerly gathered living specimens and shells from the shore near his home in Brief suburban Boston, studying and continually re- Chronology arranging his collections. Dall came from a family that valued learning. His mother was a school teacher, strict, scholarly, and brilliant. His father had studied at Harvard; a Science Unitarain missionary, he spent decades in India, Aboard the away from the family. Dall seems to have inherited Elder his mother's gift for scholarship, his father's penchant for lengthy travel. In his late teens he'd taken a job with the Land Office of the Illinois Central Railroad in Chicago, and spent a year searching for iron ore deposits in northern Michigan. Exploration & At age 20, he had joined the Western Union Settlement telegraph expedition to Alaska, the first of many trips. He was actually in Alaska, collecting specimens and making notes on Indian vocabulary, when the United States bought the territory. When that expedition was cut short, Dall had stayed on Growth another year at his own expense. Reporting on his Along efforts, he wrote "I have traveled on snow shoes, Alaska's with the thermometer from 8 to 40 below zero. -

The Cullman Library Holds Approximately 10,000 Volumes on the Natural Sciences Published Prior to 1840

THE COLLECTIONS The Cullman Library holds approximately 10,000 volumes on the natural sciences published prior to 1840. Building on the foundation of James Smithson's mineralogical books and growing with Secretary Spencer F. Baird's donation of his own working library to the U.S. National Museum in 1882, the rare- books collection has been augmented over the years by institutional purchases and exchanges, as well as by gifts and bequests from other Museum researchers and private individuals alike. The Library's holdings are cataloged and searchable in the SIL online catalog SIRIS. THE JAMES SMITHSON LIBRARY James Smithson, an 18th-century gentleman of science, included his library with his donation of $500,000 to found the Smithsonian Institution. The collection consists of about 110 titles - scientific monographs, literature, journals, and pamphlets. Inscribed and annotated volumes, including multiple copies of several of Smithson's own scientific publications, provide insights into intellectual networks of the period. Interestingly, many volumes remain in their original paper wrappers. The library thus represents a rich resource for biographers and bibliographers alike. HISTORY OF MUSEUMS & SCIENTIFIC COLLECTING The predecessors of today's museums were the private "cabinets of rarities" and "wonder rooms" of the Renaissance. Natural history collections, and the manuscripts and printed books describing them, began to be scientifically significant in the 1600s. The best of them were serious, systematic efforts to investigate and comprehend the natural world. From the 17th century on, such efforts were greatly expanded as scientific expeditions sponsored by governments, commercial interests, and the well-to-do brought exotic plants and animals back to European collections. -

Lost Villages of the Eastern Aleutians

Cupola from the Kashega Chapel in the Unalaska churchyard. Photograph by Ray Hudson, n.d. BIBLIOGRAPHY Interviews The primary interviews for this work were made in 2004 with Moses Gordieff, Nicholai Galaktionoff, Nicholai S. Lekanoff, Irene Makarin, and Eva Tcheripanoff. Transcripts are found in The Beginning of Memory: Oral Histories on the Lost Villages of the Aleutians, a report to the National Park Service, The Aleutian Pribilof Islands Restitution Fund, and the Ounalashka Corporation, introduced and edited by Raymond Hudson, 2004. Additional interviews and conversations are recorded in the notes. Archival Collections Alaska State Library Historical Collections. Samuel Applegate Papers, 1892-1925. MS-3. Bancroft Library Collection of manuscripts relating to Russian missionary activities in the Aleutian Islands, [ca. 1840- 1904] BANC MSS P-K 209. Hubert Howe Bancroft Collection Goforth, J. Pennelope (private collection) Bringing Aleutian History Home: the Lost Ledgers of the Alaska Commercial Company 1875-1897. Logbook, Tchernofski Station, May 5, 1887 – April 22, 1888 Library of Congress, Manuscript Division Russian Orthodox Greek Catholic Church of America, Diocese of Alaska Records, 1733-1938. National Anthropological Archives, Smithsonian Institution National Archives and Records Administration Record Groups 22 (Fish and Wildlife Service), 26 (Coast Guard), 36 (Customs Service), 75 (Bureau of 322 LOST VILLAGES OF THE EASTERN ALEUTIANS: BIORKA, KASHEGA, MAKUSHIN Indian Affairs) MF 720 (Alaska File of the Office of the Secretary of the Treasury, 1868-1903) MF Z13 Pribilof Islands Logbooks, 1870-1961. (Previous number A3303) Robert Collins Collection. (Private collection of letters and documents relating to the Alaska Commercial Company) Smithsonian Institution Archives Record Unit 7073 (William Healey Dall Collection) Record Unit 7176 (U.S. -

The Etyfish Project © Christopher Scharpf and Kenneth J

ESOCIFORMES · 1 The ETYFish Project © Christopher Scharpf and Kenneth J. Lazara COMMENTS: v. 3.0 - 10 Nov. 2018 Subcohort PROTACANTHOPTERYGII protos, first; acanthus, spine; pteron, fin or wing, ray-finned fishes that lack spines and therefore are presumed to resemble ancestors of spiny rayed fishes Order ESOCIFORMES 2 families · 4 genera · 15 species/subspecies Family ESOCIDAE Pikes Esox Linnaeus 1758 latinized Gaulish word for a large fish from the Rhine, possibly originally applied to a salmon, now applied to pikes Esox americanus americanus Gmelin 1789 American, distinguishing it from the circumpolar E. lucius Esox americanus vermiculatus Lesueur 1846 referring to “narrow, winding” vermiculations on sides, “closer and more tight” on females (translations) Esox aquitanicus Denys, Dettai, Persat, Hautecoeur & Keith 2014 -icus, belonging to: Aquitaine, region of southwestern France, where it was discovered Esox cisalpinus Bianco & Delmastro 2011 cis-, on this side; alpinus, alpine, referring to its distribution on one side (the Italian) of the Alps Esox lucius Linnaeus 1758 Latin for pike, referring to its long, pointed snout Esox masquinongy Mitchill 1824 Native American name for this species, from the Ojibway (Chippewa) mask, ugly; kinongé, fish [due to a bibliographic error, Mitchill’s description had been “lost” since its publication until 2015, when it was rediscovered by Ronald Fricke, upon which it was revealed that Mitchill used a vernacular name instead of proposing a new binomial; Jordan, who searched for Mitchill’s description but never found it, nevertheless treated the name as valid in 1885, a decision accepted by every fish taxonomist ever since; technically, name and/or author and/or date should change depending on first available name (not researched), but prevailing usage may apply] Esox niger Lesueur 1818 black or dark, referring to its juvenile coloration Esox reichertii Dybowski 1869 patronym not identified, probably in honor of Dybowski’s anatomy professor Karl Bogislaus Reichert (1811-1883) Esox aquitanicus. -

Nature Journal

SMITHSONIAN IN YOUR CLASSROOM FALL 2 0 0 6 Introduction to the nature journal www.SmithsonianEducation.org Contents 2 Background Introduction to the 4 Opening Discussion 6 Lesson 1 9 Lesson 2 aturejournal Never trusting to memory, he recorded every incident of which he had been the eyewitness on the spot, and all manner of observations went into his journal. He noted the brilliant grasses and flowers of the prairie, the sound of the boatman’s horn winding from afar, the hooting of the great owl and the muffled murmur of its wings as it sailed smoothly over the river. van wyck brooks on john james audubon The lessons address the following standards: NATIONAL LANGUAGE ARTS STANDARDS, GRADES K–12 NATIONAL SCIENCE EDUCATION STANDARDS, GRADES K–12 Standard 6 Content Standard A Students apply knowledge of language structure, language conventions, As a result of activities, students develop an understanding of scientific inquiry and genre to create, critique, and discuss print and nonprint texts. and abilities necessary for scientific inquiry. Standard 7 Content Standard C Students gather, evaluate, and synthesize data from a variety of sources. As a result of activities, students develop an understanding of life science. Standard 8 Smithsonian in Your Classroom is produced by the Smithsonian Center for Education Students use a variety of technological and information resources to create and Museum Studies. Teachers may duplicate the materials for educational purposes. and communicate knowledge. ILLUSTRATIONS Cover: Detail from Cardinal Grosbeak by John James Audubon, 1811, Smithsonian American Art Museum. Audubon journal page, 1843, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University. -

Clarence Leroy Andrews

CLARENCE LEROY ANDREWS Books and papers from his personal library and manuscript collection. From a bibliography compiled by the Sheldon Jackson College Library, Sitka, Alaska Collection housed in the Sitka Public Library CLARENCE LEROY ANDREWS i862 - 1948 TABLE OF CONTENTS Sheldon Jackson College - C. L. Andrews Collection Annotated Bibliography [How to use this finding aid.] [Library of Congress Classification Outline] SECTION ONE: Introduction SECTION TWO: Biographical Sketch [Provenance timeline for Andrews Collection] [Errata notes from physical inventory Aug.-Nov. 2013] SECTION THREE: Listing of Books and Periodicals SECTION FOUR: Unpublished Documents SECTION FIVE: Listing of Maps in Collection SECTION SIX:** [Archive box contents] [ ] Indicate materials added for finding aid, which were not part of original CLA bibliography. ** Original section six, Special Collection pages, were removed. Special Collections were not transferred to the Sitka Public Library. How to use the C. L. Andrews finding aid. This finding aid is a digitized copy of an original bibliography. It has been formatted to allow ‘ctrl F’ search strings for keywords. This collection was cataloged using the Library of Congress (LOC) call number classification system. A general outline is provided in this aid, and more detail about the LOC classification system is available at loc.gov. Please contact Sitka Public Library staff to make arrangements for research using this collection. To find an item: Once an item of interest is located in the finding aid, make note of the complete CALL NUM, a title and an author name. The CALL NUM will be most important to locate the item box number. The title/author information will confirm the correct item of interest. -

Seventh Annual Report of the Board of Regents of the Smithsonian Institution to the Senate and House of Representatives, Showing

University of Oklahoma College of Law University of Oklahoma College of Law Digital Commons American Indian and Alaskan Native Documents in the Congressional Serial Set: 1817-1899 3-1-1853 Seventh annual report of the board of regents of the Smithsonian institution to the Senate and House of Representatives, showing the operations, expenditures, and condition of the institution during the year 1852, and the proceedings of the board of regents up to date. Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.ou.edu/indianserialset Part of the Indian and Aboriginal Law Commons Recommended Citation S. Misc. Doc. No. 53, 32nd Cong., 2nd Sess. (1853) This Senate Miscellaneous Document is brought to you for free and open access by University of Oklahoma College of Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in American Indian and Alaskan Native Documents in the Congressional Serial Set: 1817-1899 by an authorized administrator of University of Oklahoma College of Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SEVENTH ANNUAL REPORT OF TIIE BOARD OF REGENTS OF THE SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION TO THE SENATE AND HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES, SHOWING THE OPERATIONS, EXPENDITURES, AND CONDITION OF THE INSTITUTION DURING THE YEAR 1852, AND THE .PROCEEDINGS OF THE BOARD OF REGENTS UP TO DATE. WASHING TON: ROBERT .ARMSTRONG, PRINTER. 1853. 82d CONGRESS, [SENATE.] M1scELLANEous, 2d Session. No. 53. LETTER FROM THE SECRETARY OF THE SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION, COMMUNIOATING The Annual Report of the Board of R egents. MARCH 1, 1853.-0rderei to lie on the table and be printed. SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION, A ugust 20, 1852. -

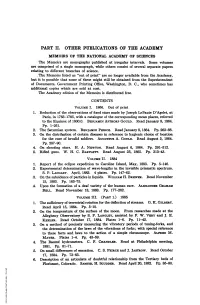

PART II. OTHER PUBLICATIONS of the ACADEMY MEMOIRS of the NATIONAL ACADEMY of SCIENCES -The Memoirs Are Monographs Published at Irregular Intervals

PART II. OTHER PUBLICATIONS OF THE ACADEMY MEMOIRS OF THE NATIONAL ACADEMY OF SCIENCES -The Memoirs are monographs published at irregular intervals. Some volumes are comprised of a single monograph, while others consist of several separate papers relating to different branches of science. The Memoirs listed as "out of print" qare no longer available from the Academy,' but it is possible that some of these might still be obtained from the Superintendent of Documents, Government Printing Office, Washington, D. C., who sometimes has additional copies which are sold at cost. The Academy edition of the Memoirs is distributed free. CONTENTS VoLums I. 1866. Out of print 1. Reduction of the observations of fixed stars made by Joseph LePaute D'Agelet, at Paris, in 1783-1785, with a catalogue of the corresponding mean places, referred to the Equinox of 1800.0. BENJAMIN APTHORP GOULD. Read January 8, 1864. Pp. 1-261. 2. The Saturnian system. BZNJAMIN Pumcu. Read January 8, 1864. Pp. 263-86. 3. On the distribution of certain diseases in reference to hygienic choice of location for the cure of invalid soldiers. AUGUSTrUS A. GouLD. Read August 5, 1864. Pp. 287-90. 4. On shooting stars. H. A. NEWTON.- Read August 6, 1864. Pp. 291-312. 5. Rifled guns. W. H. C. BARTL*rT. Read August 25, 1865. Pp. 313-43. VoLums II. 1884 1. Report of the eclipse expedition to Caroline Island, May, 1883. Pp. 5-146. 2. Experimental determination of wave-lengths in the invisible prismatic spectrum. S. P. LANGIXY. April, 1883. 4 plates. Pp. 147-2. -

Spencer Baird and the Scientific Investigation of the Northwest Atlantic, 1871-1887

Spencer Baird and the Scientific Investigation of the Northwest Atlantic, 1871-1887 Dean C. Allard Between 1871 and 1887, Spencer Fullerton Baird organized and led a pioneering biological and physical investigation of the Northwest Atlantic oceanic region. Born in Pennsylvania in 1823, Baird was largely self-educated as a scientist in the era preceding the rise of major U.S. universities.1 Nevertheless, he became a major authority on the birds, mammals, reptiles, amphibians and fishes of North America. After 1850, as the Assistant Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, DC (in 1878 he became head of that organization), Baird used the numerous exploratory expeditions that the US government sent to the far reaches of the North American continent to gather enormous collections of scientific specimens and data. Those collections were a major impetus for the National Museum that Baird was developing within the Smithsonian, and were also the basis for a number of scientific publications on the biology of North America. By the early 1870s, in addition to his long-standing concern with terrestrial biology, Baird became increasingly interested in the oceanic environment. This new emphasis apparently grew out of the summers that Baird and his family spent at various locations along the Atlantic seaboard. In addition to offering a refuge from the oppressive heat of Washington, the sea shore offered ample opportunity for Baird to study oceanic life. He also was well aware that in this era Anton Dohrn, Charles Wyville Thomson, and other scientists throughout the world were turning their attention to the sea. All these investigators recognized that the study of the maritime environment was in its infancy.