Causes and Solutions for the Recent Decline in Recorded Music Sales

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Music Industry and Digital Music

The Music Industry and Digital Music Disruptive Technology and the Value Network Effects on Industry Incumbents A thesis written by Jens Peter Larsen Cand. Merc., Master of Science, Management of Innovation & Business Development Copenhagen Business School Supervisor: Finn Valentin, Institut for innovation og organisationsøkonomi Word Count: 170.245 digits – 75 standard pages The Music Industry and Digital Music – Jens Peter Larsen, Cand. Merc. MIB Thesis Table of Content 1. Resume .................................................................................. 4 2. Introduction ............................................................................ 5 3. Research Design ....................................................................... 6 3.1 Research Question .......................................................................................................... 6 3.2 Elaboration on Research Design ................................................................................... 6 3.2.1 Technological Development ..................................................................................... 6 3.2.2 Definitions................................................................................................................. 7 4. Methodology ............................................................................ 8 4.1 Project Outlook .............................................................................................................. 9 4.2 Delimitation .................................................................................................................. -

What's the Download® Music Survival Guide

WHAT’S THE DOWNLOAD® MUSIC SURVIVAL GUIDE Written by: The WTD Interactive Advisory Board Inspired by: Thousands of perspectives from two years of work Dedicated to: Anyone who loves music and wants it to survive *A special thank you to Honorary Board Members Chris Brown, Sway Calloway, Kelly Clarkson, Common, Earth Wind & Fire, Eric Garland, Shirley Halperin, JD Natasha, Mark McGrath, and Kanye West for sharing your time and your minds. Published Oct. 19, 2006 What’s The Download® Interactive Advisory Board: WHO WE ARE Based on research demonstrating the need for a serious examination of the issues facing the music industry in the wake of the rise of illegal downloading, in 2005 The Recording Academy® formed the What’s The Download Interactive Advisory Board (WTDIAB) as part of What’s The Download, a public education campaign created in 2004 that recognizes the lack of dialogue between the music industry and music fans. We are comprised of 12 young adults who were selected from hundreds of applicants by The Recording Academy through a process which consisted of an essay, video application and telephone interview. We come from all over the country, have diverse tastes in music and are joined by Honorary Board Members that include high-profile music creators and industry veterans. Since the launch of our Board at the 47th Annual GRAMMY® Awards, we have been dedicated to discussing issues and finding solutions to the current challenges in the music industry surrounding the digital delivery of music. We have spent the last two years researching these issues and gathering thousands of opinions on issues such as piracy, access to digital music, and file-sharing. -

My Friend P2p

MY FRIEND P2P Music and Internet for the Modern Entrepreneur Lucas Pedersen Bachelor’s Thesis December 2010 Degree Program in Media Digital Sound and Commercial Music Tampereen ammattikorkeakoulu Tampere University of Applied Sciences 2 ABSTRACT Tampere University of Applied Sciences Degree Program in Media Digital Sound and Commercial Music PEDERSEN, LUCAS: My Friend p2p – Music and Internet for the Modern Entrepreneur Bachelor’s thesis 81 pages December 2010 _______________________________________________________________ The music industry is undergoing an extensive transformation due to the digital revolution. New technologies such as the PC, the internet, and the iPod are empowering the consumer and the musician while disrupting the recording industry models. The aim of my thesis was to acknowledge how spectacular these new technologies are, and what kind of business structure shifts we can expect to see in the near future. I start by presenting the underlying causes for the changes and go on to studying the main effects they have developed into. I then analyze the results of these changes from the perspective of a particular entrepreneur and offer a business idea in tune with the adjustments in supply and demand. Overwhelmed with accessibility caused by democratized tools of production and distribution, music consumers are reevaluating recorded music in relation to other music products. The recording industry is shrinking but the overall music industry is growing. The results strongly suggest that value does not disappear, it simply relocates. It is important that both musicians and industry professionals understand what their customers value and how to provide them with precisely that. _______________________________________________________________ Key Words: Music business, digital revolution, internet, piracy, marketing. -

The Music Industry in the Social Networking Era

THE MUSIC INDUSTRY IN THE SOCIAL NETWORKING ERA By Xi Yue A THESIS Submitted to Michigan State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS Telecommunication, Information Studies and Media 2011 Abstract THE MUSIC INDUSTRY IN THE SOCIAL NETWORKING ERA By Xi Yue Music has long been a pillar of profit in the entertainment industry, and an indispensable part in many people’s daily lives around the world. The emergence of digital music and Internet file sharing, spawned by rapid advancement in information and communication technologies (ICT), has had a huge impact on the industry. Music sales in the U.S., the largest national market in the world, were cut in half over the past decade. After a quick look back at the pre-digital music market, this thesis provides an overview of the music industry in the digital era. The thesis continues with an exploration of three motivating questions that look at social networking sites as a possible major outlet and platform for musical artists and labels. A case study of a new social networking music service is presented and, in conclusion, thoughts on a general strategy for the digital music industry are presented. Table of Contents List of Figures................................................................................................................................ iv List of Tables................................................................................................................................... v Introduction.................................................................................................................................... -

The Twenty Greatest Music Concerts I've Ever Seen

THE TWENTY GREATEST MUSIC CONCERTS I'VE EVER SEEN Whew, I'm done. Let me remind everyone how this worked. I would go through my Ipod in that weird Ipod alphabetical order and when I would come upon an artist that I have seen live, I would replay that concert in my head. (BTW, since this segment started I no longer even have an ipod. All my music is on my laptop and phone now.) The number you see at the end of the concert description is the number of times I have seen that artist live. If it was multiple times, I would do my best to describe the one concert that I considered to be their best. If no number appears, it means I only saw that artist once. Mind you, I have seen many artists live that I do not have a song by on my Ipod. That artist is not represented here. So although the final number of concerts I have seen came to 828 concerts (wow, 828!), the number is actually higher. And there are "bar" bands and artists (like LeCompt and Sam Butera, for example) where I have seen them perform hundreds of sets, but I counted those as "one," although I have seen Lecompt in "concert" also. Any show you see with the four stars (****) means they came damn close to being one of the Top Twenty, but they fell just short. So here's the Twenty. Enjoy and thanks so much for all of your input. And don't sue me if I have a date wrong here and there. -

Trap Pilates POPUP

TRAP PILATES …Everything is Love "The Carters" June 2018 POP UP… Shhh I Do Trap Pilates DeJa- Vu INTR0 Beyonce & JayZ SUMMER Roll Ups….( Pelvic Curl | HipLifts) (Shoulder Bridge | Leg Lifts) The Carters APESHIT On Back..arms above head...lift up lifting right leg up lower slowly then lift left leg..alternating SLOWLY The Carters Into (ROWING) Fingers laced together going Side to Side then arms to ceiling REPEAT BOSS Scissors into Circles The Carters 713 Starting w/ Plank on hands…knee taps then lift booty & then Inhale all the way forward to your tippy toes The Carters exhale booty toward the ceiling….then keep booty up…TWERK shake booty Drunk in Love Lit & Wasted Beyonce & Jayz Crazy in Love Hands behind head...Lift Shoulders extend legs out and back into crunches then to the ceiling into Beyonce & JayZ crunches BLACK EFFECT Double Leg lifts The Carters FRIENDS Plank dips The Carters Top Off U Dance Jay Z, Beyonce, Future, DJ Khalid Upgrade You Squats....($$$MOVES) Beyonce & Jay-Z Legs apart feet plie out back straight squat down and up then pulses then lift and hold then lower lift heel one at a time then into frogy jumps keeping legs wide and touch floor with hands and jump back to top NICE DJ Bow into Legs Plie out Heel Raises The Carters 03'Bonnie & Clyde On all 4 toes (Push Up Prep Position) into Shoulder U Dance Beyonce & JayZ Repeat HEARD ABOUT US On Back then bend knees feet into mat...Hip lifts keeping booty off the mat..into doubles The Cartersl then walk feet ..out out in in.. -

The Quality of Recorded Music Since Napster: Evidence Based on The

Digitization and the Music Industry Joel Waldfogel Conference on the Economics of Information and Communication Technologies Paris, October 5-6, 2012 Copyright Protection, Technological Change, and the Quality of New Products: Evidence from Recorded Music since Napster AND And the Bands Played On: Digital Disintermediation and the Quality of New Recorded Music Intro – assuring flow of creative works • Appropriability – may beget creative works – depends on both law and technology • IP rights are monopolies granted to provide incentives for creation – Harms and benefits • Recent technological changes may have altered the balance – First, file sharing makes it harder to appropriate revenue… …and revenue has plunged RIAA Total Value of US Shipments, 1994-2009 16000 14000 12000 10000 total 8000 digital $ millions physical 6000 4000 2000 0 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 Ensuing Research • Mostly a kerfuffle about whether file sharing cannibalizes sales • Oberholzer-Gee and Strumpf (2006),Rob and Waldfogel (2006), Blackburn (2004), Zentner (2006), and more • Most believe that file sharing reduces sales • …and this has led to calls for strengthening IP protection My Epiphany • Revenue reduction, interesting for producers, is not the most interesting question • Instead: will flow of new products continue? • We should worry about both consumers and producers Industry view: the sky is falling • IFPI: “Music is an investment-intensive business… Very few sectors have a comparable proportion of sales -

Illegal File Sharing

ILLEGAL FILE SHARING The sharing of copyright materials such as MUSIC or MOVIES either through P2P (peer-to-peer) file sharing or other means WITHOUT the permission of the copyright owner is ILLEGAL and can have very serious legal repercussions. Those found GUILTY of violating copyrights in this way have been fined ENORMOUS sums of money. Accordingly, the unauthorized distribution of copyrighted materials is PROHIBITED at Bellarmine University. The list of sites below is provided by Educause and some of the sites listed provide some or all content at no charge; they are funded by advertising or represent artists who want their material distributed for free, or for other reasons. Remember that just because content is free doesn't mean it's illegal. On the other hand, you may find websites offering to sell content which are not on the list below. Just because content is not free doesn't mean it's legal. Legal Alternatives for Downloading • ABC.com TV Shows • [adult swim] Video • Amazon MP3 Downloads • Amazon Instant Video • AOL Music • ARTISTdirect Network • AudioCandy • Audio Lunchbox • BearShare • Best Buy • BET Music • BET Shows • Blackberry World • Blip.fm • Blockbuster on Demand • Bravo TV • Buy.com • Cartoon Network Video • Zap2it • Catsmusic • CBS Video • CD Baby • Christian MP Free • CinemaNow • Clicker (formerly Modern Feed) • Comedy Central Video • Crackle • Criterion Online • The CW Video • Dimple Records • DirecTV Watch Online • Disney Videos • Dish Online • Download Fundraiser • DramaFever • The Electric Fetus • eMusic.com -

The Music Industry and the Fleecing of Consumer Culture

The Music Industry: Demarcating Rhyme from Reason and the Fleecing of Consumer Culture I. Introduction The recording industry has a long history rooted deep in technological achievement and social undercurrents. In place to support such an infrastructure, is a lengthy list of technological advancements, political connections, lobbying efforts, marketing campaigns, and lawsuits. Ever since the early 20th century, record labels have embarked on a perpetual campaign to strengthen their control over recording artists and those technologies and distribution channels that fuel the success of such artists. As evident through the current draconian recording contracts currently foisted on artists, this campaign has often resulted in success. However, the rise of MTV, peer-to-peer file sharing networks, and even radio itself also proves that the labels have suffered numerous defeats. Unfortunately, most music listeners in the world have remained oblivious to the business practices employed by the recording industry. As long as the appearance of artistic freedom exists, as reinforced through the media, most consumers have typically been content to let sleeping dogs lie. Such a relaxed viewpoint, however, has resulted in numerous policies that have boosted industry profits at the expense of consumer dollars. Only when blatant coercion has occurred, as evidenced through the payola scandals of the 1950s, does the general public react in opposition to such practices. Ironically though, such outbursts of conscience have only served to drive payola practices further underground—hidden behind co-operative advertising agreements and outside promotion consultants. The advent of the Internet in the last decade, however, has thrown the dynamics of the recording industry into a state of disarray. -

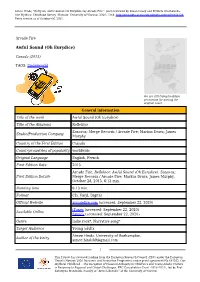

OMC | Data Export

Aimee Hinds, "Entry on: Awful Sound (Oh Eurydice) by Arcade Fire ", peer-reviewed by Susan Deacy and Elżbieta Olechowska. Our Mythical Childhood Survey (Warsaw: University of Warsaw, 2020). Link: http://omc.obta.al.uw.edu.pl/myth-survey/item/1128. Entry version as of October 06, 2021. Arcade Fire Awful Sound (Oh Eurydice) Canada (2013) TAGS: Underworld We are still trying to obtain permission for posting the original cover. General information Title of the work Awful Sound (Oh Eurydice) Title of the Album(s) Reflektor Sonovox; Merge Records / Arcade Fire; Markus Dravs; James Studio/Production Company Murphy Country of the First Edition Canada Country/countries of popularity worldwide Original Language English, French First Edition Date 2013 Arcade Fire, Reflektor: Awful Sound (Oh Eurydice), Sonovox; First Edition Details Merge Records / Arcade Fire; Markus Dravs; James Murphy, October 28, 2013, 6:13 min. Running time 6:13 min. Format CD, Vinyl, Digital Official Website arcadefire.com (accessed: September 22, 2020) iTunes (accessed: September 22, 2020) Available Onllne Spotify (accessed: September 22, 2020) Genre Indie rock*, Narrative song* Target Audience Young adults Aimee Hinds, University of Roehampton, Author of the Entry [email protected] 1 This Project has received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Programme under grant agreement No 681202, Our Mythical Childhood... The Reception of Classical Antiquity in Children’s and Young Adults’ Culture in Response to Regional and Global Challenges, ERC Consolidator Grant (2016–2021), led by Prof. Katarzyna Marciniak, Faculty of “Artes Liberales” of the University of Warsaw. -

J. Mascis Gets a Bobblehead - Stereogum

J. Mascis Gets A Bobblehead - Stereogum http://stereogum.com/929611/j-mascis-gets-a-bobblehead/news/ Sign Up Sign In Search for: Follow: News Music Videos Photos Lists MySplice: The Year Mashed Up Stroked: A Tribute to The Strokes Is This It Enjoyed: A Tribute To Bjork's Post DRIVE XV: A Tribute To R.E.M.'s Automatic For The People OKX: A Tribute To Radiohead's OK Computer RAC Vol. 1 Stereogum Shut Up, Dude: The 5 Best Videos Did Kings Of Leon Stereogum Buzz 20 Songs Named Monthly Mix: This Week’s Best Of The Week Rip Off No Age? Chart: Week Of After The Bands January 2012 And Worst 1/15/12 That Played Them Comments J. Mascis Gets A Bobblehead 4 Comments Jan 20th '12 by corban @ 1:45pm Tweet 33 Share 53 StumbleUpon 1 of 5 1/23/2012 8:50 AM J. Mascis Gets A Bobblehead - Stereogum http://stereogum.com/929611/j-mascis-gets-a-bobblehead/news/ Nerd culture collides again for Aggronautix’s new bobblehead , facsimile of J. Mascis. There is some precedent for this. But they’re thinking big this time. J is accurately sculpted right down to the big ole glasses, rockin’ riff grip, and signature silver mane that features REAL DOLL HAIR — a first for Aggronautix! Barriers are being broken here, people. I would still rather have any of these , honestly (#16 is the best). Like 53 people like this. Tags: Dinosaur Jr , J Mascis Tweet 33 Share 53 You Might Also Like J Mascis – “I’ve Been Thinking” Watch Ted Leo Interview Michael Stipe, J Mascis, Liz Phair… J Mascis – “Is It Done” J Mascis – “Not Enough” Hear Tennis Perform New Songs At Sundance The 5 Best Videos Of The Week Comments (4) mr_axed | Posted on Jan 20th awesome 1. -

A Comparative Analysis of Punk in Spain and Mexico

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive Theses and Dissertations 2018-07-01 El futuro ya está aquí: A Comparative Analysis of Punk in Spain and Mexico Rex Richard Wilkins Brigham Young University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd Part of the Spanish and Portuguese Language and Literature Commons BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Wilkins, Rex Richard, "El futuro ya está aquí: A Comparative Analysis of Punk in Spain and Mexico" (2018). Theses and Dissertations. 6997. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd/6997 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. El futuro ya está aquí: A Comparative Analysis of Punk Culture in Spain and Mexico Rex Richard Wilkins A thesis submitted to the faculty of Brigham Young University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Brian Price, Chair Erik Larson Alvin Sherman Department of Spanish and Portuguese Brigham Young University Copyright © 2018 Rex Richard Wilkins All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT El futuro ya está aquí: A Comparative Analysis of Punk Culture in Spain and Mexico Rex Richard Wilkins Department of Spanish and Portuguese, BYU Master of Arts This thesis examines the punk genre’s evolution into commercial mainstream music in Spain and Mexico. It looks at how this evolution altered both the aesthetic and gesture of the genre. This evolution can be seen by examining four bands that followed similar musical and commercial trajectories.