“You Must Be Joking”: 007 in the Laboratory and Academia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

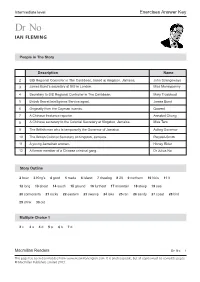

Dr No Exercises AK

Intermediate level Exercises Answer Key Dr No IAN FLEMING People in The Story Description Name 2 SIS Regional Controller in The Caribbean, based at Kingston, Jamaica. John Strangeways 3 James Bond’s secretary at SIS in London. Miss Moneypenny 4 Secretary to SIS Regional Controller in The Caribbean. Mary Trueblood 5 British Secret Intelligence Service agent. James Bond 6 Originally from the Cayman Islands. Quarrel 7AChinese freelance reporter. Annabel Chung 8 A Chinese secretary to the Colonial Secretary at Kingston, Jamaica. Miss Taro 9 The British man who is temporarily the Governor of Jamaica. Acting Governor 10 The British Colonial Secretary at Kingston, Jamaica. Pleydell-Smith 11 A young Jamaican woman. Honey Rider 12 A former member of a Chinese criminal gang. Dr Julius No Story Outline 2 hour 3 King’s 4 good 5 made 6 island 7 drawing 8 20 9 northern 10 No’s 11 It 12 long 13 about 14 south 15 ground 16 furthest 17 mountain 18 steep 19 sea 20 cormorants 21 rocks 22 eastern 23 swamp 24 lake 25 ran 26 sandy 27 coast 28 bird 29 drink 30 old Multiple Choice 1 2 c 3 a 4 d 5 a 6 b 7 d Macmillan Readers Dr No 1 This pagepage hashas beenbeen downloadeddownloaded from www.macmillanenglish.comwww.macmillanenglish.com. It. Itis is photocopiable, photocopiable, but but all all copies copies must must be be complete complete pages. ©pages. Macmillan © Macmillan Publishers Publishers Limited Limited 2013. 2005. Published by Macmillan Heinemann ELT Heinemann is a registered trademark of Harcourt Education, used under licence. -

Dr No IAN FLEMING 1 John Strangeways Works for the British Secret Intelligence Service

Intermediate level Points for Understanding Answer Key Dr No IAN FLEMING 1 John Strangeways works for the British Secret Intelligence Service. He is not a good spy, because too many people know what his work is. 2 (a) M, the Head of the Secret Service, asks this question. (b) M is talking to the British special agent, James Bond – 007. (c) Bond’s last mission had gone badly wrong and Bond had nearly been killed. M wants to be sure that Bond can be trusted not to make a mistake again. 31(a) Dr Julius No, who bought Crab Key from Britain in 1942, is a very rich man. He is half Chinese and half German. (b) They are the names of birds. Many green cormorants visit Crab Key and leave their droppings – called guano. Guano contains nitrates, so it is collected to be used as fertilizer. Roseate spoonbills are very rare birds. They now live in a sanctuary on Crab Key, to keep them safe. (c) The man was a warden from the bird sanctuary on Crab Key. His body was badly burned and he died a few days later. He said that he had been burned by a dragon which breathed fire and destroyed his camp. The other warden had been burnt to death and so had many of the spoonbills. 2 Bond thinks that Strangeways and Trueblood have been killed. 4 1 Quarrel, a man from the Cayman Islands, is going to help Bond. 2 Quarrel can help Bond in several ways. The people of Jamaica trust Quarrel and tell him things. -

Dr.No: James Bond 007 Free

FREE DR.NO: JAMES BOND 007 PDF Ian Fleming | 336 pages | 02 Aug 2012 | Vintage Publishing | 9780099576068 | English | London, United Kingdom Dr. No (novel) - James Bond Wiki Looking for a movie the entire family can enjoy? Check out our picks for family friendly movies movies that transcend all ages. For even more, visit our Family Entertainment Guide. See the full list. James Bond is Britain's top agent, and is on an exciting mission, to solve the mysterious murder of a fellow agent. The task sends him to Jamaica, where he joins forces with Quarrel and a loyal C. Agent, Felix Leiter. While dodging tarantulas, "fire breathing dragons", and a trio of assassins, known as "the three blind mice". Bond meets up Dr.No: James Bond 007 the beautiful Honey Ryder and goes face to face with the evil Dr. I recently embarked Dr.No: James Bond 007 a mission of my own. To watch all the Bond films in order. Believe me, it's not as easy as it sounds. Finding all of them is nearly impossible. Blockbuster's weak collection hardly does any justice, so I ended up buying most of my favorites. I'm sorry to say, but to me Sean Connery is the only Bond. With the single exception being Craig in "Casino Royale". When I Dr.No: James Bond 007 growing up, I did enjoy Moore's Dr.No: James Bond 007, but now his portrayal seems almost goofy. Moore was just an old guy in a tight suit. Connery seems to be the only actor that understands who or what Bond is. -

Read Book Dr.No: James Bond

DR.NO: JAMES BOND 007 PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Ian Fleming | 336 pages | 02 Aug 2012 | Vintage Publishing | 9780099576068 | English | London, United Kingdom Dr.No: James Bond 007 PDF Book Ultimately, the producers turned to 32 year-old Sean Connery for five films. Also Known As: Dr. External Sites. James Bond is Britain's top agent, and is on an exciting mission, to solve the mysterious murder of a fellow agent. After taking some punches, the driver weeps and asks to be allowed a cigarette. He manages to escape while the other car plummets off a hill and explodes. There is the "most important gesture [in] Joseph Wiseman as Dr. No's complex using the dragon-disguised swamp buggy. Color: Color. Read more about the Dr. The politics of James Bond: from Fleming's novel to the big screen. Retrieved 1 October The Jamaica Observer. The painting had been stolen from the National Gallery by a year-old amateur thief in London just before filming began. Bra: a thousand years of style, support and seduction. No, who ostensibly operates a business harvesting and exporting guano, is in fact working with the Russians. He is kept under regular observation, suffering electric shocks, burns and an encounter with large poisonous spiders along the way. Wikimedia Commons Wikiquote. Retrieved 14 October Metacritic Reviews. The voice is angry that he arrived during daytime and is angry that Bond is still alive, and will hold Dent responsible if Bond comes snooping around the island. There's a slow stretch in the middle and Dr. Dent, a geologist with a practice in Kingston, who also secretly works for Dr. -

Ts, Xl-James Bond Archives

All About James Bond! First XL-Edition Golden Edition Copies 001–500* *No. 007 not for sale; to be auctioned for charity Limited to 500 num- “We wanted to create a book that Features include: would be an appropriate tribute to this bered copies, signed incredible 50-year milestone. A book – Celebrating the 50th anniversary of the most by Daniel Craig that would show the familiar, but also things never seen before, treasures successful and longest-running film franchise in uncovered, moments long since cinema history! forgotten. A book that would look not – Made with unrestricted access to the Bond archives, just at the world of Bond films, but the world behind the films, at everything this XL tome recounts the entire history of James Bond it took to make this 50-year journey in words and pictures happen.” – Among the 1100 images are many previously unseen — Michael G. Wilson and Barbara Broccoli, EON Productions stills, on-set photos, memos, documents, storyboards, posters, and designs, plus unused concepts, and With an archival, museum- alternative designs quality pigment print THE JAMES BOND ARCHIVES – Behind-the-scenes stories from the people who were signed by legendary Bond LIMITED FIRST EDITION there: producers, directors, actors, screenwriters, set designer Sir Ken Adam Edited by Paul Duncan production designers, special effects technicians, Hardcover + film strip of Dr. No stuntmen, and other crew members 41.1 x 30 cm (16.2 x 11.8 in.), 600 pages – Chapters written by Ellen Cheshire, Danny Graydon, Howard Hughes, Colin Odell & Michelle Le Blanc, Editions: Jamie Russell, and Paul Duncan English: ISBN 978–3–8365–2105-5 – Includes every Bond film ever made, from Dr. -

World of James Bond 1St Edition Kindle

WORLD OF JAMES BOND 1ST EDITION PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Jeremy Black | 9781442276116 | | | | | World of James Bond 1st edition PDF Book Podcasts See all. They'll likely never say Never Say Never Again again. After Fleming died from a heart attack in , a book of Bond short stories was released. His Scottish father worked for a British arms manufacturer and was killed while mountain climbing along with Bond's Swiss mother when James was eleven. Save Pin ellipsis More. Top French-American chef Jean-Georges Vongerichten curates the culinary experience, and British celebrity mixologist Salvatore Calabrese oversees the bar. Army Air Corps following the attack. Chowringhee airstrip was clear. The documents shed light on the warship's early years and the young United States' first international conflict. Based on the 13th and final completed Ian Fleming Bond novel, The Man with the Golden Gun remains one of the lowest-grossing films in the entire history of the series. Even at the most tense moments, Bond finds time for a one-liner, dryly delivered with a half-smile. Unlike M, for many years there was only one Q, Major Boothroyd. All the other Pierce Brosnan Bonds might be despised by the masses, but everyone seems to agree on one thing: GoldenEye is so much better than anything else that the other three Brosnan Bonds have to offer. We also learn of his preference for "Perrier, for in his opinion, expensive soda water was the cheapest way to improve a poor drink. He rushed to develop about 30 photographs at the nearest base of operations and had them delivered to Cochran, Alison and Wingate. -

IPA Review April Working Final.Indd

THE POLITICS OF JAMES B ND The world of 007 reveals a deeper subtext to a landscape of high-tech gadgetry and martinis, writes Morgan Begg. keep and enjoy the fruits of your own In these cases and more, the labour as greedy, and which pushes individual is being asked to make MORGAN BEGG higher taxes as people paying their fair sacri ces for the ‘greater good’ of Research Scholar at the share. Or when laws are enacted to society. It is a classic calling card of Institute of Public A airs and Editor, FreedomWatch restrict free speech, on the basis that collectivism. A collectivist world-view o ensive speech might o end racial regards individuals as belonging to groups and cause untold social unrest. a wider society, and whose value as ore and more it seems Likewise, when mandatory data individuals extends only as far as it that the place and retention laws were passed in 2015, serves the purposes of the collective. importance of the Australians were told that everyone’s In contrast, an individualist Mindividual is taking privacy would have to be undermined world-view sees society as more of a backseat in Western societies. to combat terrorism (never mind that a free-association of individuals, Symptoms of this include political economic regulators such as the ATO whose value is inherent and discourse which regards the desire to and ASIC also enjoy these powers). inalienable. Individualism is at Volume 68 I 1 THE POLITICS OF JAMES BOND R the core of western liberalism, technology and high-tech gadgetry by the end of the 1950s, where and deserves modern day hero. -

James Bond Villains and Psychopathy: a Literary Analysis

JOURNAL OF PSYCHOPATHOLOGY Online First Original article 2020;Nov 15. doi: 10.36148/2284-0249-351 James Bond villains and psychopathy: a literary analysis Conor Kavanagh1, Andrea E. Cavanna1,2,3 1 Department of Neuropsychiatry, BSMHFT and University of Birmingham, Birmingham, United Kingdom; 2 School of Life and Health Sciences, Aston Brain Centre, Aston University, Birming- ham, United Kingdom; 3 Sobell Department of Motor Neuroscience and Movement Disorders, Institute of Neurology and University College London, London, United Kingdom SUMMARY Objective Psychopathy is a construct used to describe individuals without a conscience, who knowingly harm others via manipulation, intimidation, and violence, but feels no remorse. In consider- ation of the intriguing nature of the psychopathy construct, it is not surprising that a number of psychopathic characters have been portrayed in popular culture, including modern liter- ature. We set out to systematically review Ian Fleming’s James Bond novels to assess the presence of psychopathic traits in the characters of Bond villains. Methods We reviewed the full-text of a representative sample of seven novels published by Fleming between 1954 and 1965 (‘Live and let die’, ‘Dr. No’, ‘Goldfinger’, ‘Thunderball’, ‘On Her Maj- esty’s secret service’, ‘You only live twice’, and ‘The man with the golden gun’), portraying the fictional characters of six villains. For each villain, we extracted examples of quotations that demonstrate the presence of specific psychopathic traits from the Psychopathy Check- list-Revised (PCL-R). Results We found ample evidence of the presence of specific psychopathic traits from the PCL-R in Received: October 10, 2019 James Bond villains. -

Screening Geopolitics: James Bond and the Early Cold War Films (1962–1967)

Geopolitics, 10:266–289, 2005 Copyright © 2005 Taylor & Francis, Inc. ISSN: 1465-0045 print DOI: 10.1080/14650040590946584 Geopolitics102TaylorFGEOTaylor5793110.1080/146500405909465842005137JamesKlaus Dodds Bond& Francis, & andFrancisTaylor theInc. Early Coldand FrancisWar Films 325 Chestnut StreetPhiladelphiaPA191061465-0045Screening Geopolitics: James Bond and the Early Cold War films (1962–1967) KLAUS DODDS Department of Geography, Royal Holloway, University of London, Surrey, UK This paper seeks to extend the remit of popular geopolitics by con- sidering the role and significance of places and their inhabitants in shaping the narrative structures of films. By using the example of the James Bond series from the 1960s, it is suggested that there is more complex series of geographies to be acknowledged. Arguably most of the trade press reviewers were largely content to argue that places were simply ‘exotic locations’. With a detailed examination of screenplays from five Bond films, it is shown that United Artists and Eon Productions played an important and creative role in shaping the geographies of dangers and threats confronted by James Bond. Moreover, austere and or remote locations also played important roles in generating a sense of climax between the British secret agent and his enemies regardless of whether they were part of a criminal network or an evil genius. Finally, the paper concludes with an assessment of some of the outstanding challenges facing a popular geopolitics. INTRODUCTION In my experience all Prime Ministers love intelligence because it is a secret weapon they have. The intelligence report used to arrive in special little boxes and it gave them a belief that they had a direct line to some- thing that no ordinary departments have. -

James Bond a 50 Ans Et Julius No Est Toujours Vivant

actualité, info en marge revue de presse James Bond a 50 ans et Julius No Vaccins : la pénurie s’aggrave Voilà qui tombe mal. Alors que la Suisse manquait déjà de vaccins contre la grippe, le gel de la livrai est toujours vivant son des doses de Novartis n’améliore pas les choses. Hier, l’Office fédéral de la santé publique Bond (James Bond) fête aujour d’hui son traduction française en 1960. Deux ans plus (OFSP) a confirmé une aggravation de la situa demi-siècle. Cinquante ans d’existence ci né- tard, en technicolor donc, ce sera l’affronte- tion, conseillant plus que jamais aux médecins de vacciner en premier lieu les groupes à risque et matographi que, d’espionnage, de gadgets, ment entre son nouveau héros au nom d’or- leur entourage proche. de champagne et de jolies filles. Une vie en nithologue et ce génie malfaisant, fruit des Emboîtant le pas à l’Italie qui a interdit mercredi technicolor. Oui, nous con naissons. Tout a ébats entre une Chinoise et d’un pasteur al- matin l’utilisation des produits du groupe bâlois, été dit et écrit sur James Bond comme sur lemand. Le tout sur l’île de Crab Key dont il la Suisse a recommandé de ne pas utiliser les Tintin et Milou. Tout ? Peut-être pas. semble que Julius No détienne les titres de vaccins de Novartis jusqu’à nouvel ordre. Une «simple mesure de précaution» motivée par de Cinquante ans, vraiment ? Il sem ble que propriété. Outre son patrimoine génétique, petites particules blanches découvertes dans cer c’était hier. -

James Bond and the End of the World

James Bond and the End of the World ANDRÉ J. MILLARD The creation of James Bond marked a signifcant change in Ian Fleming’s view of technology. Once a technological enthusiast, a believer in the efcacy of new ideas, and a su""orter of technological change, Fleming became disillusioned with science and scientists during his intelligence work in #orld #ar II. $is fa% mous character emerged at a time of dramatic and discomforting "ost%war change in both Fleming’s "ersonal life & a marriage, a new home, a new 'ob & and in his world. As he writes in Casino Royale, )*h+istory is moving "retty ,uickly these days- ./012, /345. The dysto"ian fears grew stronger in Fleming’s fction as the 6old #ar heated u", and his o"timism for the future & as well as his health & declined. $is villains grew more ambitious, the threat of technology in the wrong hands increased e7"onentially, and the end of the world grew closer with every novel & as one of his readers told him: )*y+ou are doing your bit to make the world a beastlier "lace- .,td. in Fleming 9:/1, /9;5. As the fctionalised Bond evolved into the flmic Bond, these dystopian themes grew stronger, and the technological threat became more "otent, em% bracing terror weapons of mass destruction. Bond stood for human agency in negotiating technological change, and his inevitable triumph symbolised Flem% ing’s elief in the resilience and ingenuity of the individual. So while the charac% ter of Bond changed very little, the malicious technology he faced grew in "ace with the rapid advance of technology during the arms race that followed #orld #ar II. -

Ian Fleming the Ex-Banker, Journalist, Military Man and Secret Agent, Definitely Preferred His Martinis Shaken, Not Stirred

Ian Fleming The ex-banker, journalist, military man and secret agent, definitely preferred his Martinis shaken, not stirred. A staunch believer in 'luxury living', he was his own prototype for 007. Ian Fleming, creator of James Bond, was much like his fictional character. Fleming was a spy, a notorious womaniser and he liked his martinis shaken, not stirred. Part of the British aristocracy, he was a journalist, a banker and a military man, who finally wrote his first novel at age 43. Over the next 11 years, he wrote 13 Bond novels and the children's book 'Chitty Chitty Bang Bang'. Once translated to the silver screen, James Bond launched the world's longest running series of movies. Fleming was born in Mayfair, London, to Valentine Fleming, an MP, and his wife Evelyn Ste Croix Fleming. Ian was the younger brother of travel writer Peter Fleming and the older brother of Michael and Richard Fleming. He also had an illegitimate half-sister, the cellist Amaryllis Fleming. He was educated at Eton before going on to the Royal Military Academy at Sandhurst. After an early departure from the prestigious officer training school, he opted to study languages at a private school in Austria. Following an unsuccessful application to join the Foreign Office, Fleming worked as a sub-editor and journalist for the Reuters news agency, and then as a stockbroker in the City of London. On the eve of World War II, Fleming was recruited into naval intelligence. Owing in part to his facility with languages, he was a personal assistant to Admiral John H.