Case 5:13-Cv-02715-EEF-MLH Document 1 Filed 09/20/13 Page 1 of 20 Pageid #: 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Huie Dellmon Regular Collection

Huie Dellmon Regular Collection Item No. Subject and Description Date Place 403 Airplanes and crowd of people at airport 404 Air Circus at airport 1929 Baton Rouge, Louisiana 405 Wedell flying his butterfly in air races Baton Rouge, Louisiana 406 Crowds of people at air show 1929 Baton Rouge, city of 407 Air races at airport 1929 Baton Rouge, city of 409 Vapor trails from U. S. bombers over city Alexandria, Louisiana stand pipe 410 Vapor trails from U. S. bombers over city Alexandria, city of stand pipe 1192 Our air show with planes on port 1929 Baton Rouge, city of 1790 Jet Bomber flying at Army Day Show 35mm 8716 Pictures (very small) of a large glider overhead 5/17/1966 Pineville, Louisiana 1717 Aerial picture of aircraft carrier, Forrestal, planes on deck 376 Aerial view of upper part of town from plain farms and etc. 1861 Airplanes Jet F84 crashed in Pineville, LA. in June 1956 on or about 7:35 374 Large U. S. Airplane believed to have flown from Oklahoma camp and got lost out of Dallas, Texas, ran out of gas and landed on upper Third Street 375 Air show at airport Baton Rouge, Louisiana 386 Wrecked Ryan airplane at airport on lower Third Street, belonged to Wedell Williams Co. of Patterson, Louisiana; air service 1920's 388 Windsock for our airport on lower Third Street on Hudson property; not very successful 399 Wrecked Ryan airplane that hit a ditch on port, belongs to Weddell-Williams of Huie Dellmon Regular Collection Patterson, Louisiana 378 Two large B-50's flying low over city and river Alexandria, Louisiana 392 Old Bi-plane at airport 393 People at airport Baton Rouge, Louisiana 394 Parachute dropped at airport, in Enterprise Edition 395 People at airport 396 Large Ryan passenger plane moving on runway 397 Ryan passenger plane and pilot of Weddell Williams Company 398 Planes at airport 400 City Officials at grand opening of airport, lower Third St. -

FEDE Legister

A / ) uttcraT % J v I SCRIPTA I A I HAUET § FEDE lEGISTER VO LU M E 2 2 ^ O N n t o ^ NUMBER 16 Washington, Thursday, January 24, 1957 TITLE 6— AGRICULTURAL CREDIT Oklahom a— C ontinued CONTENTS Average Average Chapter III—-Farmers Home Adminis C ounty: value C ounty: value Agricultural Marketing Service ^ tration, Department of Agriculture Pus lima- Tillman ___ $40,000 Proposed rule making: t a h a ____ $20, 000 T u l s a ___ 30, 000 Oranges, grapefruit, and tanger Subchapter B— Farm Ownership Loans R o g e r s ____ _ 30, 000 W agon er __ 30,000 ines grown in Florida; han- [FHA Instruction 428.1] S e m in o le __ 20, 000 W a s h in g - Sequoyah _ 25,000 t o n ____ _ 30, 000 dling__________________________ 476 Part 331— P o l i c i e s a n d A u t h o r i t i e s S t e p h e n s __ 30,000 W a s h i t a __ 40,000 Rules and regulations: Tomatoes grown in Florida; ap AVERAGE VALUES OF FARMS,’ H AW AII AND (Sec. 41 (1 ), 60 Stat. 1066; 7 TJ. S. C. 1015 (1 )) proval of expenses and rate of OKLAHOMA Dated: January 17, 1957. assessment__________________ - 471 On December 20,1956, for the purposes [ s e a l ] H. C. S m i t h , Agriculture Department of Title I of the Bankhead-Jones Farm Acting Administrator, See Agricultural Marketing Serv Tenant Act, as amended, average values Farmers Home Administration. -

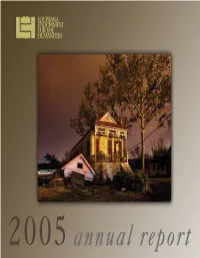

2005 Annual Report

A NNUAL R EPORT Contents PAGE 1 Board and Staff PAGE 2 Introduction PAGE 4 PRIME TIME Family Reading Time PAGE 5 Louisiana Cultural Vistas Magazine PAGE 6 Readings in Literature and Culture (RELIC) PAGE 7 Teacher Institutes for Advanced Study PAGE 8 Grants Grants Analysis (p. 8-9) Teaching American History (p. 10) Key Ingredients: America by Food (p. 11) Southern Humanities Media Fund (p. 11) About the cover: Our Town (p.12) Humanist of the Year (p.12) Photographer Frank Relle’s image titled Laussat, of a raised State Poet Laureate (p.12) Creole shotgun house in New Orleans standing beside a Public Humanities Grants (p. 13) home that collapsed during the fury of Hurricane Katrina, epitomizes the mix of resilience and destruction that Documentary Film & Radio Grants (p. 15) defined 2005 in the hard-hit regions of South Louisiana. Louisiana Publishing Initiative (p. 16) Outreach Grants (p. 18) American Routes (p. 21) Tennessee Williams (p. 21) PAGE 22 2004 Humanities Awards PAGE 23 Past Board of Directors PAGE 24 2004 Donors to the LEH Board of Directors Administrative Staff Consultants DIANNE BRADY LINDA SPRADLEY Project Co-Director Legislative Liaison NANCY GUIDRY PRIME TIME Metairie FAMILY READING TIME ® LINDA LANGLEY Program Education SANDRA GUNNER MICHAEL FAYE FLANANGAN New Orleans SARTISKY, Project Co-Director JOHN F. T REMBLEY R. LEWIS PH.D. PRIME TIME Network Administrator MCHENRY, MARK H. HELLER, CLU, CPC FAMILY READING TIME J.D. ® New Orleans President/ LAURA LADENDORF, Executive MIRANDA RESTOVIC KARIN MARTIN, CHAIRMAN, WILLIAM JENKINS, PH.D. Director Assistant Director New Orleans TOAN NGUYEN, Baton Rouge PRIME TIME & BECCA RAPP JOHN R. -

Louisiana State Law Institute Recognizes 70-Year Milestone: Origin, History and Accomplishments

Louisiana State Law Institute Recognizes 70-Year Milestone: Origin, History and Accomplishments By William E. Crawford & Cordell H. Haymon ol. John H. Tucker, Jr. and Dean Paul M. Hebert of the Loui- siana State University (LSU) Law School, in 1938 and 1951, Crespectively, memorialized the origin of the Louisiana State Law Institute. Col. Tucker said: This organization originated in a movement, initiated here at the LSU Law School in 1933, to es- tablish an institute dedicated to law revision, law reforms and legal re- search. Due to economic reasons, that project was postponed until April 1938, when the Board of Supervisors authorized its revival, under its present name. The Legis- lature, later in the year, chartered, created and organized it as “an of- ficial, advisory law reform com- mission, law reform agency and legal research agency of the State of Louisiana.” The purposes of the institute are de- clared by the Legislature to be: “to promote and encourage the clarifica- tion and simplification of the law of Louisiana and its better adaptation to present social needs; to secure the John H. Tucker, Jr. Photo provided by the Louisiana State Law Institute. better administration of justice and to carry on scholarly legal research and scientific legal work.” . This Law Institute. In the speech, he further with the Law School, of a research is the first time in the history of this made note of the official pronouncement organization to be known as the State that Legislative recognition by then-LSU President James Monroe Louisiana State Law Institute. This has been given to a long recognized Smith at the dedication of the Law School action of the Board amounts to a need and an adequate organization on April 7, 1938: revival of a similar project which established to meet it. -

Records of Ante-Bellum Southern Plantations from the Revolution Through the Civil War General Editor: Kenneth M

A Guide to the Microfilm Edition of Records of Ante-Bellum Southern Plantations from the Revolution through the Civil War General Editor: Kenneth M. Stampp Series M Selections from the Virginia Historical Society Part 3: Other Tidewater Virginia Associate Editor and Guide Compiled by Martin Schipper A microfilm project of UNIVERSITY PUBLICATIONS OF AMERICA An Imprint of CIS 4520 East-West Highway • Bethesda, MD 20814-3389 i Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Records of ante-bellum southern plantations from the Revolution through the Civil War [microform] Accompanied by printed reel guides, compiled by Martin Schipper. Contents: ser. A. Selections from the South Caroliniana Library, University of South Carolina (2 pts.)—[etc.]—ser. L. Selections from the Earl Gregg Swem Library, College of William and Mary—ser. M. Selections from the Virginia Historical Society. 1. Southern States—History—1775–1865—Sources. 2. Slave records—Southern States. 3. Plantation owners—Southern States—Archives. 4. Southern States— Genealogy. 5. Plantation life—Southern States— History—19th century—Sources. I. Stampp, Kenneth M. (Kenneth Milton) II. Boehm, Randolph. III. Schipper, Martin Paul. IV. South Caroliniana Library. V. South Carolina Historical Society. VI. Library of Congress. Manuscript Division. VII. Maryland Historical Society. [F213] 975 86-892341 ISBN 1-55655-527-X (microfilm : ser. M, pt. 3) Compilation © 1995 by Virginia Historical Society. All rights reserved. ISBN 1-55655-527-X. TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction........................................................................................................................... -

Download a PDF Version of the Guide to African American Manuscripts

Guide to African American Manuscripts In the Collection of the Virginia Historical Society A [Abner, C?], letter, 1859. 1 p. Mss2Ab722a1. Written at Charleston, S.C., to E. Kingsland, this letter of 18 November 1859 describes a visit to the slave pens in Richmond. The traveler had stopped there on the way to Charleston from Washington, D.C. He describes in particular the treatment of young African American girls at the slave pen. Accomack County, commissioner of revenue, personal property tax book, ca. 1840. 42 pp. Mss4AC2753a1. Contains a list of residents’ taxable property, including slaves by age groups, horses, cattle, clocks, watches, carriages, buggies, and gigs. Free African Americans are listed separately, and notes about age and occupation sometimes accompany the names. Adams family papers, 1698–1792. 222 items. Mss1Ad198a. Microfilm reels C001 and C321. Primarily the papers of Thomas Adams (1730–1788), merchant of Richmond, Va., and London, Eng. Section 15 contains a letter dated 14 January 1768 from John Mercer to his son James. The writer wanted to send several slaves to James but was delayed because of poor weather conditions. Adams family papers, 1792–1862. 41 items. Mss1Ad198b. Concerns Adams and related Withers family members of the Petersburg area. Section 4 includes an account dated 23 February 1860 of John Thomas, a free African American, with Ursila Ruffin for boarding and nursing services in 1859. Also, contains an 1801 inventory and appraisal of the estate of Baldwin Pearce, including a listing of 14 male and female slaves. Albemarle Parish, Sussex County, register, 1721–1787. 1 vol. -

Front Matter (1940)

Louisiana State University Law Center LSU Law Digital Commons Compiled Edition of the Civil Codes of Louisiana Front Matter (1940) Front Matter Louisiana Recommended Citation Louisiana, "Front Matter" (1940). Front Matter. 1. http://digitalcommons.law.lsu.edu/la_civilcode_book_frontmatter/1 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Compiled Edition of the Civil Codes of Louisiana (1940) at LSU Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Front Matter by an authorized administrator of LSU Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. LOUISIANA LEGAL ARCHIVES Volume 3 Part I \!:om,pil�� -f�ition of the (tivil (to��s of-(ouisiana Prepared by THE LOUISIANA STATE LAW INSTITUTE at the direction of THE EDITORIAL COMMITTEE and E. A. CONWAY, Secretary of State E. A. CONWAY, Jn., Secretary of State (Feb. 22 to May 17, 1940) Published Pursuant to Act 165 of the Legislature of Louisiana of 1938 ]AMES A. GREMILLION, Secretary of State Baton Rouge, Louisiana 1940 Copyright, 1940 By The State of Louisiana TABLE OF CONTENTS LOUISIANA LEGAL ARCHIVES, Vol. 3, Part I Page THE ADVISORY COMMITTEE FOR THE COMPILED CODES. • . • . v AcT 165 OF 1938 (authorizing and ordering the present work) . vn THE EDITORIAL COMMITTEE AND EXTRACT OF MINUTES. • . IX THE LOUISIANA STATE LAW INSTITUTE................... XI FOREWORD . • . • . • . • . • . • • • . • . • • . • . • • • . • . XIll . EXPLANATORY NOTES • • • • • • • • . • • . • • • • • • • . • . • • • • • • . xvii ABBREVIATIONS . • • . • . • • . • • • • • • • • • • • . • • • • • • • . XXI TABLE OF CONTENTS OF REVISED CIVIL CODE OF LOUISIANA. • . xxm ARTICLES 1-1755 OF THE COMPILED CODES. • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • 1-968 { ARTICLES 1756-3556 OF THE COMPILED CODES ••••• CONTENTS OF LOUISIANA APPENDICES. • . • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • . • • • • • • . LEGAL ARCHIVES , . • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • . • • • • • • INDEX. • • Vol. -

United Professional Company

UNITED PROFESSIONAL COMPANY RESPONSE TO LOUISIANA PUBLIC SERVICE COMMISSION REQUEST FOR PROPOSALS 20-02 FOR OUTSIDE CONSULTANT IN LPSC RFP 20-02, DOCKET NO. X-35500, JEFFERSON DAVIS ELECTRIC COOPERATIVE, INC. AND DIXIE ELECTRIC MEMBERSHIP CORPORATION, EX PARTE. IN RE: NOTICE OF INTENT TO CONDUCT 2020 REQUEST FOR PROPOSALS FOR LONG- TERM POWER PURCHASES CONTRACTS AND/OR GENERATING CAPACITY PURSUANT TO THE COMMISSION'S MARKET BASED MECHANISM ("MBM") ORDER. SUBMITTAL DATE: APRIL 02, 2020 PREPARED AND SUBMITTED BY: UNITED PROFESSIONALS COMPANY 201 ST. CHARLES, AVE., STE. 4240 NEW ORLEANS, LOUISIANA 70170-1048 TABLE OF CONTENTS A. Executive Summary .................................................................................................................0 B. Qualifications and Experience ..................................................................................................1 1. The Sisung Group .............................................................................................................1 2. United Professionals Company .........................................................................................2 C. Plan of Action .........................................................................................................................11 1. Methodology ...................................................................................................................12 2. Approach .........................................................................................................................12 -

Rosters of State Officials

fS Rosters of State Officials PRINCIPAl L STATE OFFICERS PRINCIPAL EXECUTIVE OFFICERS—1945 . SlaU , CaotTtwrs LituUnant GoiHfnofs . Attortuys Gaural • SecretatUs of Siatt ALABAMA,.. ,. Chauncey M. Spark* >.. L. Handy Eilif Robert B.-Harwood Mi« Sibyl Pool ARIZONA. Sidney P, Cbborn , John L, Sullivan, Dan E, Garvcy ARKANSAS., Benjamin T. Laney T, L, Shaver Guy E, Willianu^, ' C. G. Hall CALIFORNIA..,,.., Earl Warren Frederick F. Houier .Robert W, Kenny Frank M.Jordan COLORADO John C. Vivian William E, Higby H. Lawrence Hinkley Walter F, Morrijon CONNECrrCUT..,. Raymond E.Baldwin Wilbert Snow , William L, Hadden CharlciJ, Pre«tia DELAWARE Walter W. Bacon Elbert N. Carvel Clair John Killoran William J. Storey FLORIDA... .,,. Millard F. Caldwell , J. Tom Wauon Robert A. Gray • • <• . • • v . GEORGIA-...,.,,., Elli*G.AmalI ... .,...,,..,,, Eugene Cook John B, WiUon IDAHO,, Charle* C, Go«ett Arnold Williams Frank Langley Ira H. Master* ILLINOIS..... Dwight H, Green Hiigh W. Cross • George P. Barrett Edward J. Barrett ; . INDIANA........... Ralph F.Gatei Puchard T, James James A, Emmert Rue J. Alexander ' XOWA , RobertD.Blue K.A.Evans John M. Rankin Wayne M, Ropes KANSAS, ,, Andrew F, Schoeppcl Jess C. Denious A, B, Mitchell, Frank J, Ryan KENTUCKY..,,,.;, Simeon S, Willis Kenneth H, Tuggle Eldon .S. Diimmit Chirles K. O'Connell LOUISIANA .,. i, James H, Davis J, Emile Verret Fred S, LcBlanc Wade O. Mardn, Jfr, MAINE Horace A, Hildreth .,... Ralph W, Farris Harold I, Gois MARYLAND...,..-. Herbert R. 0*Conor ; William Curran William J. McWilliams MASSACHUSETTS,, Maurice J. Tobin Robert F. Bradford Clarence A. Barnes Frederi? W. Cook MICHIGAN , Harry F. Kelly Vernon J, Brown John R, Dcihmcrs Herman H. -

Ariail Family Tree 11Thst Generation

AriAil fAmily Tree Book 4. This is the research that has been completed as of Dec 2019. We know for certain that the father of ***Mathieu Ariail (1) was ***Francois Ariail and his mother was Mathurine Cornu. We believe the father of ***Francois Ariail was ***Jean (John) Ariail and mother to be Francoise Brunier. Still looking at records and can make corrections if necessary. The reason for this assumption is that ***Jean Ariail and Francoise Brunier named one of their sons Herve Ariail, bap. 22 Aug 1626, and the name Herve Ariail is used down through this line of the family and has been found in no other line of the family. So here goes. Documentation comes from www.culture.cg44.fr and www.archives49.fr. The ancestors of all the Ariail Family living in the U.S. and Arial in Canada are marked with ORANGE***. There are some Arial Families living in the U.S., especially Hawaii, who came from Portugal. This is not surprising, as we believe the Family name Ariail to be Hebrew in origin, migrating at some point to perhaps Spain and then to France and North America by way of Canada and Portugal. Nationality portions of U.S. Census reports support this stand. You should note that there are several lines of the Ariail family in France, each one dating back to the early 1600’s. As of this date, we have not been able to tie all of them together, but we do know that there was a Martin Ariail, born in the early 1500’s who could be a common ancestor for many of these lines. -

2014 Annual Report He Louisiana Endowment for the Humanities Is Committed to Delivering Access to the State’S Cultural Heritage to All of Louisiana’S Citizens

Be Inspired by Louisiana 2014 Annual Report he Louisiana Endowment for the Humanities is committed to delivering access to the state’s cultural heritage to all of Louisiana’s citizens. Each year, we fund and produce exhibits, lectures, public programs, publications and workshops. Each day, we warmly extend invitations to analyze, interpret and participate in Louisiana’s stirring literary traditions, historical narratives and distinctly inventive sounds and icons. Now, we are saying thank you to all of our supporters. Thank you for sustaining the humanities in Louisiana. Miranda Restovic Michael Bernstein President/Executive Director Chair II LOUISIANA ENDOWMENT FOR THE HUMANITIES We graciously acknowledge our supporters. Humanities Hero: BHP Billiton Petroleum BHP Billiton Petroleum, a British-Australian natural resource mining corporation, expressed incredible commitment to sustainability, integrity and respect in the LEH’s literacy programming through a $540,000 partnership with PRIME TIME Inc., a humanities-focused and outcomes-based program designed to engage underserved children and families around the act of reading. Over three years, BHP Billiton Petroleum will support approximately 100 PRIME TIME Inc. programs across seven parishes (Bossier, Caddo, Desoto, Lafourche, Orleans, Red River and Terrebonne), reaching more than 2,500 children ages three to five and their caregivers. From adventures and life lessons found in timeless children’s books, kids and adults share their own thoughts, opinions and creative ideas about the characters and storylines. These reading-and-discussion sessions come to life in a fun, safe and inclusive environment. Our community-rooted recruitment systems allow us to reach new, struggling and reluctant readers and introduce children to the joy of reading. -

WYES Informed Sources Archive 5 Boxes Special Collections

WYES Informed Sources Archive 5 boxes Special Collections & Archives J. Edgar & Louise S. Monroe Library Loyola University New Orleans Collection 29 WYES Informed Sources Archive Reference Code Collection 29 Name and Location of Repository Special Collections and Archives, J. Edgar & Louise S. Monroe Library, Loyola University New Orleans Title WYES Informed Sources Archive Date 1984 - Present Extent 5 boxes Subject Headings WYES-TV (Television station : New Orleans, La.) Administrative/Biographical History In 1984, WYES, New Orleans' public television station, began broadcasting Informed Sources, a program devoted to in-depth discussion of the news by local journalists. During that first show, a panel of journalists speculated about the reasons for the financial dilemmas of the Louisiana World Exposition, locally known as the World's Fair. Now more than two decades later, every Friday night at 7:00 p.m., Louisiana's newsmen and women continue to speculate, discuss and examine the news of the week. The idea for Informed Sources originated in 1971 on WYES with City Desk, a news and talk show, which featured the staff of the New Orleans States-Item and ran for seven seasons. The station had been without a news program for several years when Marcia Kavanaugh Radlauer, an experienced television reporter and independent producer, was asked to create a new show. Like City Desk, the format was a panel discussion of current news, but instead of featuring journalists from only one source, a variety of participants from television, radio, newspapers and eventually, online newsletters contributed their talents and expertise. Informed Sources originally included a "Newsmakers" interview to help fill the half-hour, but before long that segment was omitted.