A Picture of Our Health 2014 Community Health Assessment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TRIBAL COUNCIL REPORT COVID-19 TESTING and DISEASE in FIRST NATIONS on RESERVE JULY 26, 2021 *The Reports Covers COVID-19 Testing Since the First Reported Case

TRIBAL COUNCIL REPORT COVID-19 TESTING AND DISEASE IN FIRST NATIONS ON RESERVE JULY 26, 2021 *The reports covers COVID-19 testing since the first reported case. The last TC report provided was on Monday July 19, 2021. DOTC Total Cases 252 Recovered Cases 240 New Cases 1 Active Cases 4 Total Deaths 8 FARHA Total Cases 1833 Recovered Cases 1814 New Cases 1 Active Cases 8 Total Deaths 11 Independent-North Total Cases 991 Recovered Cases 977 New Cases 0 Active Cases 4 Total Deaths 10 This summary report is intended to provide high-level analysis of COVID-19 testing and disease in First Nations on reserve by Tribal Council Region since first case until date noted above. JULY 26, 2021 Independent- South Total Cases 425 Recovered Cases 348 New Cases 36 Active Cases 74 Total Deaths 3 IRTC Total Cases 651 Recovered Cases 601 New Cases 11 Active Cases 38 Total Deaths 12 KTC Total Cases 1306 Recovered Cases 1281 New Cases 1 Active Cases 15 Total Deaths 10 This summary report is intended to provide high-level analysis of COVID-19 testing and disease in First Nations on reserve by Tribal Council Region since first case until date noted above. JULY 26, 2021 SERDC Total Cases 737 Recovered Cases 697 New Cases 14 Active Cases 31 Total Deaths 9 SCTC Total Cases 1989 Recovered Cases 1940 New Cases 11 Active Cases 31 Total Deaths 18 WRTC Total Cases 377 Recovered Cases 348 New Cases 2 Active Cases 25 Total Deaths 4 This summary report is intended to provide high-level analysis of COVID-19 testing and disease in First Nations on reserve by Tribal Council Region since first case until date noted above. -

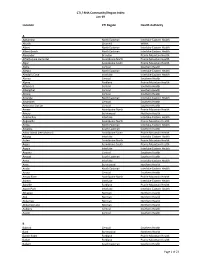

CTI / RHA Community/Region Index Jan-19

CTI / RHA Community/Region Index Jan-19 Location CTI Region Health Authority A Aghaming North Eastman Interlake-Eastern Health Akudik Churchill WRHA Albert North Eastman Interlake-Eastern Health Albert Beach North Eastman Interlake-Eastern Health Alexander Brandon Prairie Mountain Health Alfretta (see Hamiota) Assiniboine North Prairie Mountain Health Algar Assiniboine South Prairie Mountain Health Alpha Central Southern Health Allegra North Eastman Interlake-Eastern Health Almdal's Cove Interlake Interlake-Eastern Health Alonsa Central Southern Health Alpine Parkland Prairie Mountain Health Altamont Central Southern Health Albergthal Central Southern Health Altona Central Southern Health Amanda North Eastman Interlake-Eastern Health Amaranth Central Southern Health Ambroise Station Central Southern Health Ameer Assiniboine North Prairie Mountain Health Amery Burntwood Northern Health Anama Bay Interlake Interlake-Eastern Health Angusville Assiniboine North Prairie Mountain Health Anola North Eastman Interlake-Eastern Health Arbakka South Eastman Southern Health Arbor Island (see Morton) Assiniboine South Prairie Mountain Health Arborg Interlake Interlake-Eastern Health Arden Assiniboine North Prairie Mountain Health Argue Assiniboine South Prairie Mountain Health Argyle Interlake Interlake-Eastern Health Arizona Central Southern Health Amaud South Eastman Southern Health Ames Interlake Interlake-Eastern Health Amot Burntwood Northern Health Anola North Eastman Interlake-Eastern Health Arona Central Southern Health Arrow River Assiniboine -

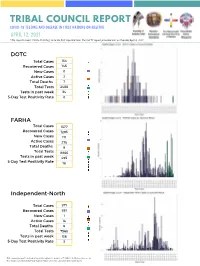

Copy of Green and Teal Simple Grid Elementary School Book Report

TRIBAL COUNCIL REPORT COVID-19 TESTING AND DISEASE IN FIRST NATIONS ON RESERVE APRIL 12, 2021 *The reports covers COVID-19 testing since the first reported case. The last TC report provided was on Tuesday April 6, 2021. DOTC Total Cases 154 Recovered Cases 145 New Cases 0 Active Cases 2 Total Deaths 7 Total Tests 2488 Tests in past week 34 5-Day Test Positivity Rate 0 FARHA Total Cases 1577 Recovered Cases 1293 New Cases 111 Active Cases 275 Total Deaths 9 Total Tests 8866 Tests in past week 495 5-Day Test Positivity Rate 18 Independent-North Total Cases 871 Recovered Cases 851 New Cases 1 Active Cases 14 Total Deaths 6 Total Tests 7568 Tests in past week 136 5-Day Test Positivity Rate 3 This summary report is intended to provide high-level analysis of COVID-19 testing and disease in First Nations on reserve by Tribal Council Region since first case until date noted above. APRIL 12, 2021 Independent- South Total Cases 218 Recovered Cases 214 New Cases 1 Active Cases 2 Total Deaths 2 Total Tests 1932 Tests in past week 30 5-Day Test Positivity Rate 6 IRTC Total Cases 380 Recovered Cases 370 New Cases 0 Active Cases 1 Total Deaths 9 Total Tests 3781 Tests in past week 55 5-Day Test Positivity Rate 0 KTC Total Cases 1011 Recovered Cases 948 New Cases 39 Active Cases 55 Total Deaths 8 Total Tests 7926 Tests in past week 391 5-Day Test Positivity Rate 10 This summary report is intended to provide high-level analysis of COVID-19 testing and disease in First Nations on reserve by Tribal Council Region since first case until date noted above. -

Directory – Indigenous Organizations in Manitoba

Indigenous Organizations in Manitoba A directory of groups and programs organized by or for First Nations, Inuit and Metis people Community Development Corporation Manual I 1 INDIGENOUS ORGANIZATIONS IN MANITOBA A Directory of Groups and Programs Organized by or for First Nations, Inuit and Metis People Compiled, edited and printed by Indigenous Inclusion Directorate Manitoba Education and Training and Indigenous Relations Manitoba Indigenous and Municipal Relations ________________________________________________________________ INTRODUCTION The directory of Indigenous organizations is designed as a useful reference and resource book to help people locate appropriate organizations and services. The directory also serves as a means of improving communications among people. The idea for the directory arose from the desire to make information about Indigenous organizations more available to the public. This directory was first published in 1975 and has grown from 16 pages in the first edition to more than 100 pages in the current edition. The directory reflects the vitality and diversity of Indigenous cultural traditions, organizations, and enterprises. The editorial committee has made every effort to present accurate and up-to-date listings, with fax numbers, email addresses and websites included whenever possible. If you see any errors or omissions, or if you have updated information on any of the programs and services included in this directory, please call, fax or write to the Indigenous Relations, using the contact information on the -

Regional Stakeholders in Resource Development Or Protection of Human Health

REGIONAL STAKEHOLDERS IN RESOURCE DEVELOPMENT OR PROTECTION OF HUMAN HEALTH In this section: First Nations and First Nations Organizations ...................................................... 1 Tribal Council Environmental Health Officers (EHO’s) ......................................... 8 Government Agencies with Roles in Human Health .......................................... 10 Health Canada Environmental Health Officers – Manitoba Region .................... 14 Manitoba Government Departments and Branches .......................................... 16 Industrial Permits and Licensing ........................................................................ 16 Active Large Industrial and Commercial Companies by Sector........................... 23 Agricultural Organizations ................................................................................ 31 Workplace Safety .............................................................................................. 39 Governmental and Non-Governmental Environmental Organizations ............... 41 First Nations and First Nations Organizations 1 | P a g e REGIONAL STAKEHOLDERS FIRST NATIONS AND FIRST NATIONS ORGANIZATIONS Berens River First Nation Box 343, Berens River, MB R0B 0A0 Phone: 204-382-2265 Birdtail Sioux First Nation Box 131, Beulah, MB R0H 0B0 Phone: 204-568-4545 Black River First Nation Box 220, O’Hanley, MB R0E 1K0 Phone: 204-367-8089 Bloodvein First Nation General Delivery, Bloodvein, MB R0C 0J0 Phone: 204-395-2161 Brochet (Barrens Land) First Nation General Delivery, -

Part1 Gendiff.Qxp

Sex Differences in Health Status, Health Care Use, and Quality of Care: A Population-Based Analysis for Manitoba’s Regional Health Authorities November 2005 Manitoba Centre for Health Policy Department of Community Health Sciences Faculty of Medicine, University of Manitoba Randy Fransoo, MSc Patricia Martens, PhD The Need to KnowTeam (funded through CIHR) Elaine Burland, MSc Heather Prior, MSc Charles Burchill, MSc Dan Chateau, PhD Randy Walld, BSc, BComm (Hons) This report is produced and published by the Manitoba Centre for Health Policy (MCHP). It is also available in PDF format on our website at http://www.umanitoba.ca/centres/mchp/reports.htm Information concerning this report or any other report produced by MCHP can be obtained by contacting: Manitoba Centre for Health Policy Dept. of Community Health Sciences Faculty of Medicine, University of Manitoba 4th Floor, Room 408 727 McDermot Avenue Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada R3E 3P5 Email: [email protected] Order line: (204) 789 3805 Reception: (204) 789 3819 Fax: (204) 789 3910 How to cite this report: Fransoo R, Martens P, The Need To Know Team (funded through CIHR), Burland E, Prior H, Burchill C, Chateau D, Walld R. Sex Differences in Health Status, Health Care Use and Quality of Care: A Population-Based Analysis for Manitoba’s Regional Health Authorities. Winnipeg, Manitoba Centre for Health Policy, November 2005. Legal Deposit: Manitoba Legislative Library National Library of Canada ISBN 1-896489-20-6 ©Manitoba Health This report may be reproduced, in whole or in part, provided the source is cited. 1st Printing 10/27/2005 THE MANITOBA CENTRE FOR HEALTH POLICY The Manitoba Centre for Health Policy (MCHP) is located within the Department of Community Health Sciences, Faculty of Medicine, University of Manitoba. -

Alumni Magazine

Pork Processing student Darian Roulette inside WINTER 2019 the meat processing centre in Sandy Bay. ALUMNI IN ACCTION SUCCESS IN SANDY BAY FIRST NATION PAGES 2-3 » 2019 Graduate stats » New scholarship for every Manitoba high school Assiniboine Pork Processing Program instructor Adrienne Mousseau demonstrates correct handling techniques. LEARNERS BECOME TEACHERS IN SANDY BAY FIRST NATION Inside of three years, more than 100 individuals have graduated from Assiniboine Community College’s Pork Processing program in Sandy Bay Ojibway First Nation. The unique partnership between Sandy Bay and Assiniboine has even seen some graduates return to the program as faculty members. The intensive 12-week program covers essential skills, safety “One of the intentions of this program was to encourage and pork processing knowledge. Graduates are recognized women to become more involved in the trades industry,” with a Pork Processing certificate, and prepared to work with said Chief Lance Roulette of Sandy Bay First Nation. “It has food processing organizations. One major employer, Hylife had a large positive impact on the community; students are Foods, operates a pork processing plant in Neepawa an hour attaining success and finding jobs.” away from the community. Many graduates have gone on to work at Hylife, which has prompted the company to provide Some students have been so successful that they’ve come a shuttle service to and from Sandy Bay for employees. full circle and are now faculty members within the program. Adrienne Mousseau was a graduate from the program’s Delivering the program in Sandy Bay has allowed first cohort of students. A top student, Mousseau has since Assiniboine to provide customized training for students who returned to the program as an instructor. -

Manitoba Association of Native Firefighters, Inc. (MANFF) Was Formed in 1991

ManitobaManitoba AssociationAssociation ofof NativeNative Firefighters,Firefighters, Inc.Inc. History of MANFF The Manitoba Association of Native Firefighters, Inc. (MANFF) was formed in 1991. Our membership is composed of, and directed by, Manitoba First Nation Fire Chiefs. We receive direction from the Fire Chiefs, who elect Board of Directors. Our Mandate In 1991, MANFF received the mandate to continue to deliver the following programs to First Nation communities: ➱Fire Safety ➱Emergency Management ➱Public Education Contribution Agreement We at MANFF, along with the Assembly of Manitoba Chiefs (AMC) and the Department of Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada (AANDC) entered into a Contribution Agreement for the delivery of Regional Fire Safety and Emergency Management programs. First Nations Emergency Management We provide Emergency Management services to First Nations on 24 hours, 7 days a week basis to First Nations, including Response, Mitigation & Recovery. ➱Emergency Response Plan Development ➱Emergency Social Services ➱Disaster Financial Assistance (DFA) ➱ Work with EMO to complete First Nation DFA Inspections Improved Emergency Operations Centre We improved our EOC with many productive upgrades, including multiple screens to monitor databases and satellite imagery; and also installed a SMARTboard in our training facility. Emergency Response Plans Upon review of the Spring Flood Report issued by Manitoba Water Stewardship, we began assisting with Emergency Response Plans, and preparing for future implementation for the following First Nation communities: Interlake Sandbag Operation In March, we worked with Manitoba EMO and the Department of Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development (AANDC) to assist with the surrounding First Nation communities, which included: •Pinaymootang •Little Saskatchewan •Lake St. Martin. The Site Operation was at the Pinaymootang Arena. -

Tribal Council Report Covid-19 Testing and Disease in First Nations on Reserve

TRIBAL COUNCIL REPORT COVID-19 TESTING AND DISEASE IN FIRST NATIONS ON RESERVE FEBRUARY 22, 2021 DOTC Total Cases 151 Recovered Cases 134 New Cases 1 Active Cases 10 Total Deaths 7 Total Tests 2253 Daily Tests 2 5-Day Test Positivity Rate 2 FARHA Total Cases 1099 Recovered Cases 906 New Cases 2 Active Cases 185 Total Deaths 8 Total Tests 6252 Daily Tests 21 5-Day Test Positivity Rate 18 Independent-North Total Cases 656 Recovered Cases 395 New Cases 23 Active Cases 258 Total Deaths 3 Total Tests 6135 Daily Tests 0 5-Day Test Positivity Rate 21 This summary report is intended to provide high-level analysis of COVID-19 testing and disease in First Nations on reserve by Tribal Council Region since first case until date noted above. FEBRUARY 22, 2021 Independent- South Total Cases 205 Recovered Cases 195 New Cases 1 Active Cases 8 Total Deaths 2 Total Tests 1712 Daily Tests 2 5-Day Test Positivity Rate 8 IRTC Total Cases 379 Recovered Cases 363 New Cases 0 Active Cases 7 Total Deaths 9 Total Tests 3470 Daily Tests 4 5-Day Test Positivity Rate 4 KTC Total Cases 845 Recovered Cases 784 New Cases 1 Active Cases 55 Total Deaths 6 Total Tests 6098 Daily Tests 23 5-Day Test Positivity Rate 7 This summary report is intended to provide high-level analysis of COVID-19 testing and disease in First Nations on reserve by Tribal Council Region since first case until date noted above. FEBRUARY 22, 2021 SERDC Total Cases 566 Recovered Cases 430 New Cases 2 Active Cases 130 Total Deaths 6 Total Tests 3573 Daily Tests 30 5-Day Test Positivity Rate 5 SCTC Total Cases 566 Recovered Cases 430 New Cases 2 Active Cases 130 Total Deaths 6 Total Tests 3573 Daily Tests 30 5-Day Test Positivity Rate 5 WRTC Total Cases 15 Recovered Cases 15 New Cases 0 Active Cases 0 Total Deaths 0 Total Tests 1261 Daily Tests 9 5-Day Test Positivity Rate 0 This summary report is intended to provide high-level analysis of COVID-19 testing and disease in First Nations on reserve by Tribal Council Region since first case until date noted above. -

Home Ground: a First Nations Perspective

asian diasporic visual cultures and the americas 2 (2016) 255-263 brill.com/adva Home Ground: A First Nations Perspective Robert Houle First Nations artist, member of Sandy Bay First Nation, Manitoba, Canada [email protected] The following is the transcript of Robert Houle’s keynote lecture for the one-day symposium Home Ground: Canadian Perspectives, which took place 6 December 2015 at the Aga Khan Museum in Toronto, Ontario, Canada. Greetings everyone. Welcome to the traditional territory of the Mississauga, to Paradise (as the Western Hemisphere was initially referred to during the Quattrocento, when Europeans began to arrive). Ozhahwushquah Penaise dezhenekanego, “I am known as Blue Thunder,” in my maternal language, Saul- teaux. This is the spirit name given to me by a shaman from my community of Sandy Bay First Nation in southern Manitoba. Today I would like to talk with you about the politics of identity from a First Nations perspective and what inspires my work. An artist begins by painting what he knows. It would be fair to say that the two are interconnected, and I will use six works of mine to establish that point, as well as an historical image of an identity more personal. Morningstar, a 1999 site-specific multimedia installation at the Pool of the Black Star in the rotunda of the Manitoba Legislature in Winnipeg, is an affir- mation of a journey home mediated by memory that lies somewhere between material and process (fig. 1). The naming and mapping of Manitoba’s sixty-one First Nations around the circumference of the steps, the mantra-like sound of recorded water hitting rocks, intertwined with drumming and the singing of a Grand Entry Song and brightly-lit coloured lights of yellow, blue, purple, and red symbolizing the hem of Rainbow Woman’s skirt, emerge as a multisensory- induced reclamation of a spiritual and political place. -

Environmental Services 200 Saulteaux Crescent Winnipeg, MB R3J 3W3 1-866-626-4862

Environmental Services 200 Saulteaux Crescent Winnipeg, MB R3J 3W3 1-866-626-4862 www.manitoba.ca HAZARDOUS WASTE GENERATOR REGISTRATIONS – MANITOBA Please report any errors/omissions/changes to Hazardous Waste Program at [email protected] COMPANY REG. NO. LOCATION CITY 18 WHEELER SAFETY & REPAIR MBG11286 500 GEORGE AVE Winkler 180 COLLISION MBG12350 SE 06-03-04 W Winkler 1ST KLASS MECHAN-X MBG10693 5 MAIN ST Grunthal 2 & 10 WRECKING LTD MBG03513 SW 02-08-19 W Carroll 3314138 MANITOBA LTD MBG12371 2061 BROOKSIDE BLVD Winnipeg 36 ST MARY'S ROAD AUTO SERVICE MBG06547 36 ST MARY'S RD Winnipeg 360 AUTOMOTIVE MBG11628 1427 SELKIRK AVE Winnipeg 3C AUTO CLINIC MBG05224 50-646 WHYTEWOLD RD Winnipeg 3M CANADA INC MBG00093 400 ROUTE 100 Morden 3M CANADA INC MBG10243 43 TERRACON PL Winnipeg 4 AV FUELS MBG12388 759 GREENWOOD AVE Selkirk 433 AUTO BODY MBG03290 433 TURENNE Winnipeg 4348037 MANITOBA LTD MBG12244 120 JAMES AV Winnipeg 49 NORTH FORWARDING MBG02417 NE 09-11-25 W Woodworth 4TRACKS LTD MBG12849 374 EAGLE DR Winnipeg 59'ER ESSO MBG10872 847 DUNNING RD E St. Clements 7-ELEVEN MBG06683 3360 VICTORIA AVE W Brandon 7-ELEVEN MBG06680 104 REGENT AVE Winnipeg 7-ELEVEN MBG06679 1131 NAIRN AVE Winnipeg 7-ELEVEN MBG06691 120 KEEWATIN ST Winnipeg 7-ELEVEN MBG06690 1622 ST MARY'S RD Winnipeg 7-ELEVEN MBG06681 1-801 REGENT AVE Winnipeg 7-ELEVEN MBG06689 1863 HENDERSON HWY Winnipeg 7-ELEVEN MBG06678 456 TALBOT AVE Winnipeg 7-ELEVEN MBG06686 627 ELLICE AVE Winnipeg 7-ELEVEN MBG06688 920 ARCHIBALD ST Winnipeg A & A AUTO SERVICES MBG10589 26 -

2017-2018 MFNSS Annual Report

MANITOBA FIRST NATIONS SCHOOL SYSTEM | 2017-2018 ANNUAL REPORT Manitoba First Nations Education Resource Centre Inc. is guided by the following vision and mission statements: VISION Support First Nations to develop and implement a comprehensive holistic educational system inclusive of First Nations languages, world views, values, beliefs, and traditions with exemplary academic standards, under First Nation jurisdiction. MISSION To help First Nations improve education for all learners to achieve: mino-pimatisiwin. Cree, Ojibwe, Ojibwe-Cree To help First Nations improve education for all learners to achieve: honso aynai. Dene To help First Nations improve education for all learners to achieve: tokadakiya wichoni washte. Dakota CONTENTS MESSAGES Chairperson ......................................................................................................................................................... 1 Executive Director ............................................................................................................................................... 2 MANITOBA FIRST NATIONS SCHOOL SYSTEM ................................................................3 School Profiles ................................................................................................................................4 Miskooseepi School ........................................................................................................................................... 4 Sergeant Tommy Prince School .....................................................................................................................