Reacting to a Transition the Case of Goa

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Newspaper Wise.Xlsx

PRINT MEDIA COMMITMENT REPORT FOR DISPLAY ADVT. DURING 2013-2014 CODE NEWSPAPER NAME LANGUAGE PERIODICITY COMMITMENT(%)COMMITMENTCITY STATE 310672 ARTHIK LIPI BENGALI DAILY(M) 209143 0.005310639 PORT BLAIR ANDAMAN AND NICOBAR 100771 THE ANDAMAN EXPRESS ENGLISH DAILY(M) 775695 0.019696744 PORT BLAIR ANDAMAN AND NICOBAR 101067 THE ECHO OF INDIA ENGLISH DAILY(M) 1618569 0.041099322 PORT BLAIR ANDAMAN AND NICOBAR 100820 DECCAN CHRONICLE ENGLISH DAILY(M) 482558 0.012253297 ANANTHAPUR ANDHRA PRADESH 410198 ANDHRA BHOOMI TELUGU DAILY(M) 534260 0.013566134 ANANTHAPUR ANDHRA PRADESH 410202 ANDHRA JYOTHI TELUGU DAILY(M) 776771 0.019724066 ANANTHAPUR ANDHRA PRADESH 410345 ANDHRA PRABHA TELUGU DAILY(M) 201424 0.005114635 ANANTHAPUR ANDHRA PRADESH 410522 RAYALASEEMA SAMAYAM TELUGU DAILY(M) 6550 0.00016632 ANANTHAPUR ANDHRA PRADESH 410370 SAKSHI TELUGU DAILY(M) 1417145 0.035984687 ANANTHAPUR ANDHRA PRADESH 410171 TEL.J.D.PATRIKA VAARTHA TELUGU DAILY(M) 546688 0.01388171 ANANTHAPUR ANDHRA PRADESH 410400 TELUGU WAARAM TELUGU DAILY(M) 154046 0.003911595 ANANTHAPUR ANDHRA PRADESH 410495 VINIYOGA DHARSINI TELUGU MONTHLY 18771 0.00047664 ANANTHAPUR ANDHRA PRADESH 410398 ANDHRA DAIRY TELUGU DAILY(E) 69244 0.00175827 ELURU ANDHRA PRADESH 410449 NETAJI TELUGU DAILY(E) 153965 0.003909538 ELURU ANDHRA PRADESH 410012 ELURU TIMES TELUGU DAILY(M) 65899 0.001673333 ELURU ANDHRA PRADESH 410117 GOPI KRISHNA TELUGU DAILY(M) 172484 0.00437978 ELURU ANDHRA PRADESH 410009 RATNA GARBHA TELUGU DAILY(M) 67128 0.00170454 ELURU ANDHRA PRADESH 410114 STATE TIMES TELUGU DAILY(M) -

Annualrepeng II.Pdf

ANNUAL REPORT – 2007-2008 For about six decades the Directorate of Advertising and on key national sectors. Visual Publicity (DAVP) has been the primary multi-media advertising agency for the Govt. of India. It caters to the Important Activities communication needs of almost all Central ministries/ During the year, the important activities of DAVP departments and autonomous bodies and provides them included:- a single window cost effective service. It informs and educates the people, both rural and urban, about the (i) Announcement of New Advertisement Policy for nd Government’s policies and programmes and motivates print media effective from 2 October, 2007. them to participate in development activities, through the (ii) Designing and running a unique mobile train medium of advertising in press, electronic media, exhibition called ‘Azadi Express’, displaying 150 exhibitions and outdoor publicity tools. years of India’s history – from the first war of Independence in 1857 to present. DAVP reaches out to the people through different means of communication such as press advertisements, print (iii) Multi-media publicity campaign on Bharat Nirman. material, audio-visual programmes, outdoor publicity and (iv) A special table calendar to pay tribute to the exhibitions. Some of the major thrust areas of DAVP’s freedom fighters on the occasion of 150 years of advertising and publicity are national integration and India’s first war of Independence. communal harmony, rural development programmes, (v) Multimedia publicity campaign on Minority Rights health and family welfare, AIDS awareness, empowerment & special programme on Minority Development. of women, upliftment of girl child, consumer awareness, literacy, employment generation, income tax, defence, DAVP continued to digitalize its operations. -

The Case of Goa, India

109 ■ Article ■ The Formation of Local Public Spheres in a Multilingual Society: The Case of Goa, India ● Kyoko Matsukawa 1. Introduction It was Jurgen Habermas, in his Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere [1991(1989)], who drew our attention to the relationship between the media and the public sphere. Habermas argued that the public sphere originated from the rational- critical discourse among the reading public of newspapers in the eighteenth century. He further claimed that the expansion of powerful mass media in the nineteenth cen- tury transformed citizens into passive consumers of manipulated public opinions and this situation continues today [Calhoun 1993; Hanada 1996]. Habermas's description of historical changes in the public sphere summarized above is based on his analysis of Europe and seems to come from an assumption that the mass media developed linearly into the present form. However, when this propo- sition is applied to a multicultural and multilingual society like India, diverse forms of media and their distribution among people should be taken into consideration. In other words, the media assumed their own course of historical evolution not only at the national level, but also at the local level. This perspective of focusing on the "lo- cal" should be introduced to the analysis of the public sphere (or rather "public spheres") in India. In doing so, the question of the power of language and its relation to culture comes to the fore. 松 川 恭 子Kyoko Matsukawa, Faculty of Sociology, Nara University. Subject: Cultural Anthropology. Articles: "Konkani and 'Goan Identity' in Post-colonial Goa, India", in Journal of the Japa- nese Association for South Asian Studies 14 (2002), pp.121-144. -

Press Release 2018

S.no Status Publication Headlines/Notes Mumbai Diary: Thursday Dossier: A sunshine 1 PUBLISHED Midday fest 2 PUBLISHED United News of India Serendipity Arts announces charpoi Challenge Serendipity Arts announces 'Charpai 3 PUBLISHED WebIndia 123 - UNI Challenge' A special Charpai Challenge’with ADI and 4 PUBLISHED Punekar News Serendipity Arts Foundation at Creaticity A special Charpai Challenge’with ADI and 5 PUBLISHED NRI News 24x7 Serendipity Arts Foundation at Creaticity Sunshine Pune - A special Charpai Challenge with ADI and 6 PUBLISHED Blogspot Serendipity Arts Foundation at Creaticity Indulge, The New Curtain raiser: Serendipity Arts Festival 2018 7 PUBLISHED Indian Express opens with grand performance, art dialogue Pune Mirror, The 8 PUBLISHED Future weave Times of India A special Charpai Challenge’with ADI and 9 PUBLISHED Pune Diary.com Serendipity Arts Foundation at Creaticity 10 PUBLISHED Mint lounge Small cities, bigger art shows Serendipity Arts Festival Announces the 11 PUBLISHED Matters of Art Charpai Challenge Everything You Need To Do In Mumbai This 12 PUBLISHED Whats Hot Week : Sept 17 To 20 The New Indian 13 PUBLISHED They too have stories to tell Express Serendipity Arts Festival 2018 curtain raiser 14 PUBLISHED United News of India event 15 PUBLISHED Sunday Midday Serendipity At The Royal Opera House Ahmedabad Mirror, 16 PUBLISHED Picking up the ropes of charpai challenge The Times of India Goa’s Serendipity Arts Festival to Hold 17 PUBLISHED Eaves Rock Curtain Raiser Events in Mumbai Business Standard - Goa's Serendipity -

US Asian Wire Distribution Points

US Asian Wire Distribution Points NewMediaWire’s comprehensive US Asian Wire delivers your news to targeted media in the Asian American community. Reaches leading Asian−American media outlets and over 375 trades and magazines dealing with political, finance, education, community, lifestyle and legal issues impacting Asian Americans as well as Online databases and websites that feature or cover Asian−American news and issues and The Associated Press. Please note, NewMediaWire includes free distribution to trade publications and newsletters. Because these are unique to each industry, they are not included in the list below. To get your complete NewMediaWire distribution, please contact your NewMediaWire account representative at 310.492.4001. aahar Newspaper Adhra Pradesh Times Newspaper Afternoon Despatch and Courier Newspaper Agence Kampuchea Press Newspaper Akila Daily Newspaper Algorithmica Japonica Newspaper am730 Newspaper Anand Rupwate Newspaper Andhra News Newspaper Andrha Pradesh Times Newspaper ANTARA News Agency Newspaper ASAHI PASOCOM Newspaper ASAHI SHIMBUN Newspaper Asahi Shimbun Newspaper Asahi Shimbun International Satellite Ed Newspaper Asia Insurance Review Newspaper Asia Pacific Management News Newspaper Asia Source Newspaper ASIA TIMES Newspaper Asian Affairs: An American Review Newspaper Asian American Press Newspaper Asian American Times Online Newspaper Asian Enterprise Magazine Newspaper Asian Focus Newspaper Asian Fortune Newspaper Asian Herald Newspaper Asian Industrial Reporter Newspaper Asian Journal Newspaper -

Annexure-Iii

ANNEXURE-III LIST OF PUBLICATION UNITS TO WHOM QUESTIONAIRE WAS SENT SL.NO. NAME OF PUBLICATION PLACE CODE LANGUAGE CIRCULATION 1 Pledge Hyderabad 100076 ENG 50463 2 Hindi Milap Hyderabad 120304 HIN 31167 3 Siyasat Hyderabad 160006 URD 42744 4 Andhra Jyothi Hyderabad 410093 TEL 33281 5 Andhra Prabha Hyderabad 410014 TEL 25000 6 Prajashakti Hyderabad 410173 TEL 11387 7 Tel.J.D.Patrika Vaartha Hyderabad 410151 TEL 101241 8 Ushodayam S.Dina.Patrika Hyderabad 410148 TEL 30719 9 Andhra Prabha Karimnagar 410207 TEL 25000 10 Deccan Chronicle Secunderabad 100447 ENG 222849 11 Andhra Bhoomi Secunderabad 410119 TEL 8258 12 Neti Manadesam Vijayawada 410214 TEL 25000 13 Vijayabhanu Visakhapatnam 410007 TEL 65256 14 Visakha Samachram Visakhapatnam 410123 TEL 55500 15 Assam Tribune Guwahati 100050 ENG 58547 16 North East Times Guwahati 100442 ENG 8418 17 Sentinel Guwahati 100074 ENG 44483 18 Purvanchal Prahari Guwahati 122350 HIN 14679 19 AJI Guwahati 300074 ASS 54466 20 Ajir-Asom Guwahati 300036 ASS 11160 21 Amar Asom Guwahati 300071 ASS 46916 22 Asomiya Khabar Guwahati 300078 ASS 46999 23 Asomiya Pratidin Guwahati 300068 ASS 59910 24 Dainik Agradoot Guwahati 300069 ASS 25000 25 Dainik Asam Guwahati 300001 ASS 12376 26 Jugasankha Guwahati 310558 BEN 82681 27 Dainik Sonar Cachar Silchar 310005 BEN 25000 28 The Hindustan Times Patna 100215 ENG 25000 29 Qaumi Tanzeem Patna 160014 URD 46842 30 Sangam Patna 100010 URD 47091 31 The Asian Age Ahmedabad 100719 ENG 22936 32 Alp Viram Ahmedabad 123493 HIN 76843 33 Gujarat Vaibhav Ahmedabad 123908 HIN 231315 -

5. Suo Moto Cognizance- Astitva Pratap

NATIONAL JUDICIAL ACADEMY RESEARCH REPORT ON: SUO MOTO COGNIZANCE/ACTION BY THE SUPREME COURT AND HIGH COURTS IN INDIA AFTER 2000 SUBMITTED BY: . ASTITVA PRATAP SINGH (INTERN 11/05/2015- 04/05/2015) . NATIONAL LAW UNIVERSITY ODISHA, CUTTACK TABLE OF CONTENTS LEVEL I ANALYSIS: ........................................................................................................ 4 Supreme Court .................................................................................................................. 4 Allahabad High Court ....................................................................................................... 6 Andhra Pradesh High Court .............................................................................................. 9 Bombay High Court ........................................................................................................ 11 Calcutta High Court ........................................................................................................ 13 Chhattisgarh High Court ................................................................................................. 14 Delhi High Court ............................................................................................................ 14 Guwahati High Court ...................................................................................................... 17 Gujarat High Court ......................................................................................................... 18 Himachal Pradesh High Court ....................................................................................... -

Profile – ARTHUR FERNANDES

Profile – ARTHUR FERNANDES Arthur Fernandes has graduated in Abnormal and Developmental Psychology and completed his Masters in Industrial Psychology from Fergusson College, Pune. As a child, he developed a fond liking for music at the age of six and has been inspired ever since. He went on to perform for his school and college and played an integral part in featuring them on the national level competition charts. He has achieved National level certificates for fine art, been awarded for outstanding contribution & performance in music in Fergusson College & awarded as a leader in the group for organizational skills and contributed to the success of the cultural program and a session in the soft skills development course conducted under the guidance of the Pune University. He further on worked in the Human Resource at Infosys BPO in the Employee Relations Department and handled one of the largest profiles there. He was responsible for Employee Engagement, Employee Assistance, Employee Emergencies / Health Management, Employee Induction for over 5000 employees in the BPO sector. He has also led and managed large events successfully at zero budget. Through his years of experience in music, he has learnt that music is a universal language and can heal. He uses music as the core for counselling, workshops or motivational talks. He is a certified Arts Based Therapist and facilitates Drum Circles on a large scale for communities, NGO’s and corporates, in Pune, Mumbai, Bangalore and Goa. Apart from this he is a Musician, a Drummer and also plays the guitar and keyboard. He teaches the same. -

Preserving Transcultural Heritage.Indb

Edited by Joaquim Rodrigues dos Santos PRESERVING TRANSCULTURAL HERITAGE: YOUR WAY OR MY WAY? Questions on Authenticity, Identity and Patrimonial Proceedings in the Safeguarding of Architectural Heritage Created in the Meeting of Cultures TITLE EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE Preserving Transcultural Heritage: Joaquim Rodrigues dos Santos (chairman) Your Way or My Way? Maria de Magalhães Ramalho Questions on Authenticity, Identity and Patrimonial Inês Cristovão Proceedings in the Safeguarding of Architectural Tiago Rodrigues Heritage Created in the Meeting of Cultures Cátia Reis Vera Mariz EDITOR Luis Urbano Afonso Joaquim Rodrigues dos Santos Margarida Donas Botto (ARTIS – Institute of Art History, School of Arts and Humanities, University of Lisbon) The authors are responsible for their texts and the images contained on them, including the correct SCIENTIFIC COMMITTEE reference of their sources and the permissions from Vítor Serrão (chairman) the copyright owners. Ana Tostões Christopher Marrion Francisco Lopez Morales LAYOUT Gill Chitty Fernanda Cavalheiro Giovanni Carbonara Margarida de Almeida Hélder Carita Javier Rivera Blanco ISBN Joaquim Rodrigues dos Santos 978-989-658-467-2 Johannes Widodo Jorge Correia DOI José Delgado Rodrigues 10.30618/978-989-658-467-2 Kassim Omar Khalid El Harrouni LEGAL DEPOSIT NUMBER Luís Urbano Afonso 428851/17 Maria João Neto Maria Lúcia Bressan Pinheiro ISSUE Nobuko Inaba 07.2017 Olga Sevan Paulo Peixoto Rabindra Vasavada Rosa Perez Rui Fernandes Póvoas Susan Jackson-Stepowski EDIÇÃO Tamás Fejérdy CALEIDOSCÓPIO -

Impact of Social Media Online Newspaper in India

International Journal of Library and Information Studies Vol.5(2) Apr-Jun, 2015 ISSN: 2231-4911 Impact of Social Media Online Newspaper In India Santosh Kumar Kori Jr. Library Assistant Indian Law Institute New Delhi. India e-mail: [email protected] Piya Chhabra Librarian (Gr.-III) All India Institute of Medical Science Raipur e-mail:[email protected] ABSTRACT Social media(SM) have provided new opportunities for online newspapers in the world. We can use of them as a powerful tool for communication. This study determines the use of the social media tools in Indian online newspaper. The objective of this study to find out maximum implication social networking tools like facebook, Twitter, linkdin as well as other social media tools in Indian online newspapers. Total 69 online newspapers were analyzed out of 68 online newspapers have using web 2.0 application for instant information sharing in public domain. Keywords: Social Media Tools (SMTs), Online Newspaper, New Technologies, Facebook, Twitter, India 1. Introduction The advent of New Communication Technology (NCT) has brought forth a set of opportunities and challenges for conventional media. The presence of new media and the Internet in particular, has posed a challenge to conventional media, especially the printed newspaper. The concept of social media(SM) is not consistently defined. There are various way to describe the concept although a common definition has not been yet been established. as a starting point the concept of social media will be understood in a technology oriented sense as web-based application, enabling many-to many communication and online publishing. -

Locating the Breach | Land Conflict Watch, India

Mapping the nature of land conflicts in India Authors: Thomas Worsdell and Kumar Sambhav Data research: Thomas Worsdell, Mrinali Karthick, and Moushumi Sharma Case studies: Nihar Gokhale, Bhasker Tripathi, and Manira Choudhury Case studies supervision: Ankur Paliwal Data collection and field documentation: Field researchers (Appendix 1) Editor: Nitin Sethi Layout Design: Naveed Dadan Cover Design: Aashna Gupta Maps: Pradeep Koulgi Copyediting: The Clean Copy (www.thecleancopy.com) Copyright: The report, its contents, or a part of them, may be republished or reproduced for non-commercial use with full citation and reference to the original as “Worsdell, T. and Shrivastava, K. (2020). Locating the Breach: Mapping the Nature of Land Conflicts in India. New Delhi: Land Conflict Watch.” Publishers: Nut Graph LLP, Rights and Resources Initiative, and Oxfam India Contents Acknowledgements 1 Background 01 2 A Quick Glance at the Principal Findings 03 3 Methodology 06 4 Data Analysis 09 5 Thematic Analysis and Emerging Policy Issues 32 6 Research Agenda for the Future 37 7 Appendices 38 List of Tables Sectors and their Sub- Sectors 10 Number of Conflicts and People Affected Across Different Tenures 14 Conflicts Classified by Types of Common Lands 16 Sector-wise Number of Conflicts in Fifth Schedule Districts and Those Affected by Left-wing Extremism (LWE) 20 Conflicts by Tenure Type in Districts with LWE 21 Conflicts by Different Common Land in Districts with LWE 22 Parties Opposed to the Communities in Conflicts 22 Conflicts by Type of Common Land in Fifth Schedule -

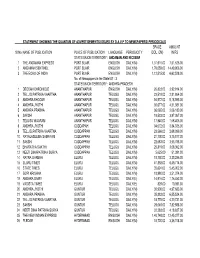

Statement Showing the Quantum of Advertisements

STATEMENT SHOWING THE QUANTUM OF ADVERTISEMENTS ISSUED BY D.A.V.P TO NEWSPAPERS/ PERIODICALS SPACE AMOUNT Sl No NAME OF PUBLICATION PLACE OF PUBLICATION LANGUAGE PERIODICITY (COL .CM) IN RS STATE/UNION TERRITORY : ANDAMAN AND NICOBAR 1 THE ANDAMAN EXPRESS PORT BLAIR ENGLISH DAILY(M) 1,31,916.00 7,51,625.00 2 ANDAMAN SENTINEL PORT BLAIR ENGLISH DAILY(M) 1,76,059.00 14,49,906.00 3 THE ECHO OF INDIA PORT BLAIR ENGLISH DAILY(M) 1,12,515.90 6,62,528.00 No. of Newspapers in the State/UT : 3 STATE/UNION TERRITORY : ANDHRA PRADESH 1 DECCAN CHRONICLE ANANTHAPUR ENGLISH DAILY(M) 26,823.00 3,92,914.00 2 TEL.J.D.PATRIKA VAARTHA ANANTHAPUR TELUGU DAILY(M) 23,519.00 2,81,864.00 3 ANDHRA BHOOMI ANANTHAPUR TELUGU DAILY(M) 54,572.00 5,18,595.00 4 ANDHRA JYOTHI ANANTHAPUR TELUGU DAILY(M) 30,677.00 4,31,381.00 5 ANDHRA PRABHA ANANTHAPUR TELUGU DAILY(M) 36,065.00 2,06,189.00 6 SAKSHI ANANTHAPUR TELUGU DAILY(M) 18,533.00 3,87,367.00 7 TELUGU WAARAM ANANTHAPUR TELUGU DAILY(M) 17,940.00 1,68,405.00 8 ANDHRA JYOTHI CUDDAPAH TELUGU DAILY(M) 34,072.00 3,84,335.00 9 TEL.J.D.PATRIKA VAARTHA CUDDAPPAH TELUGU DAILY(M) 23,566.00 2,68,399.00 10 RAYALASEEMA SAMAYAM CUDDAPPAH TELUGU DAILY(M) 21,700.00 3,75,877.00 11 SAKSHI CUDDAPPAH TELUGU DAILY(M) 22,683.00 3,95,788.00 12 BHARATHA SAKTHI CUDDAPPAH TELUGU DAILY(M) 25,819.00 3,08,362.00 13 NEETI DINAPATRIKA SURYA CUDDAPPAH TELUGU DAILY(M) 5,625.00 51,391.00 14 RATNA GARBHA ELURU TELUGU DAILY(M) 18,750.00 3,33,285.00 15 ELURU TIMES ELURU TELUGU DAILY(M) 41,858.00 6,49,774.00 16 STATE TIMES ELURU TELUGU DAILY(M) 35,624.00