A Systematic Single Nucleotide Polymorphism Screen to Fine-Map

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Retrocopy Contributions to the Evolution of the Human Genome Robert Baertsch*1, Mark Diekhans1, W James Kent1, David Haussler1 and Jürgen Brosius2

BMC Genomics BioMed Central Research article Open Access Retrocopy contributions to the evolution of the human genome Robert Baertsch*1, Mark Diekhans1, W James Kent1, David Haussler1 and Jürgen Brosius2 Address: 1Center for Biomolecular Science and Engineering, University of California Santa Cruz, Santa Cruz, California 95064, USA and 2Institute of Experimental Pathology, ZMBE, University of Münster, Von-Esmarch-Str. 56, D-48149, Münster, Germany Email: Robert Baertsch* - [email protected]; Mark Diekhans - [email protected]; W James Kent - [email protected]; David Haussler - [email protected]; Jürgen Brosius - [email protected] * Corresponding author Published: 8 October 2008 Received: 17 March 2008 Accepted: 8 October 2008 BMC Genomics 2008, 9:466 doi:10.1186/1471-2164-9-466 This article is available from: http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2164/9/466 © 2008 Baertsch et al; licensee BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Abstract Background: Evolution via point mutations is a relatively slow process and is unlikely to completely explain the differences between primates and other mammals. By contrast, 45% of the human genome is composed of retroposed elements, many of which were inserted in the primate lineage. A subset of retroposed mRNAs (retrocopies) shows strong evidence of expression in primates, often yielding functional retrogenes. Results: To identify and analyze the relatively recently evolved retrogenes, we carried out BLASTZ alignments of all human mRNAs against the human genome and scored a set of features indicative of retroposition. -

Population Genetic Considerations for Using Biobanks As International

Carress et al. BMC Genomics (2021) 22:351 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12864-021-07618-x REVIEW Open Access Population genetic considerations for using biobanks as international resources in the pandemic era and beyond Hannah Carress1, Daniel John Lawson2 and Eran Elhaik1,3* Abstract The past years have seen the rise of genomic biobanks and mega-scale meta-analysis of genomic data, which promises to reveal the genetic underpinnings of health and disease. However, the over-representation of Europeans in genomic studies not only limits the global understanding of disease risk but also inhibits viable research into the genomic differences between carriers and patients. Whilst the community has agreed that more diverse samples are required, it is not enough to blindly increase diversity; the diversity must be quantified, compared and annotated to lead to insight. Genetic annotations from separate biobanks need to be comparable and computable and to operate without access to raw data due to privacy concerns. Comparability is key both for regular research and to allow international comparison in response to pandemics. Here, we evaluate the appropriateness of the most common genomic tools used to depict population structure in a standardized and comparable manner. The end goal is to reduce the effects of confounding and learn from genuine variation in genetic effects on phenotypes across populations, which will improve the value of biobanks (locally and internationally), increase the accuracy of association analyses and inform developmental efforts. Keywords: Bioinformatics, Population structure, Population stratification bias, Genomic medicine, Biobanks Background individuals, families, communities and populations, ne- Association studies aim to detect whether genetic vari- cessitated genomic biobanks. -

Gene Linkage and Genetic Mapping 4TH PAGES © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC

© Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION Gene Linkage and © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC 4NOTGenetic FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTIONMapping NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION CHAPTER ORGANIZATION © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC NOT FOR4.1 SALELinked OR alleles DISTRIBUTION tend to stay 4.4NOT Polymorphic FOR SALE DNA ORsequences DISTRIBUTION are together in meiosis. 112 used in human genetic mapping. 128 The degree of linkage is measured by the Single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) frequency of recombination. 113 are abundant in the human genome. 129 The frequency of recombination is the same SNPs in restriction sites yield restriction for coupling and repulsion heterozygotes. 114 fragment length polymorphisms (RFLPs). 130 © Jones & Bartlett Learning,The frequency LLC of recombination differs © Jones & BartlettSimple-sequence Learning, repeats LLC (SSRs) often NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTIONfrom one gene pair to the next. NOT114 FOR SALEdiffer OR in copyDISTRIBUTION number. 131 Recombination does not occur in Gene dosage can differ owing to copy- Drosophila males. 115 number variation (CNV). 133 4.2 Recombination results from Copy-number variation has helped human populations adapt to a high-starch diet. 134 crossing-over between linked© Jones alleles. & Bartlett Learning,116 LLC 4.5 Tetrads contain© Jonesall & Bartlett Learning, LLC four products of meiosis. -

CD29 Identifies IFN-Γ–Producing Human CD8+ T Cells With

+ CD29 identifies IFN-γ–producing human CD8 T cells with an increased cytotoxic potential Benoît P. Nicoleta,b, Aurélie Guislaina,b, Floris P. J. van Alphenc, Raquel Gomez-Eerlandd, Ton N. M. Schumacherd, Maartje van den Biggelaarc,e, and Monika C. Wolkersa,b,1 aDepartment of Hematopoiesis, Sanquin Research, 1066 CX Amsterdam, The Netherlands; bLandsteiner Laboratory, Oncode Institute, Amsterdam University Medical Center, University of Amsterdam, 1105 AZ Amsterdam, The Netherlands; cDepartment of Research Facilities, Sanquin Research, 1066 CX Amsterdam, The Netherlands; dDivision of Molecular Oncology and Immunology, Oncode Institute, The Netherlands Cancer Institute, 1066 CX Amsterdam, The Netherlands; and eDepartment of Molecular and Cellular Haemostasis, Sanquin Research, 1066 CX Amsterdam, The Netherlands Edited by Anjana Rao, La Jolla Institute for Allergy and Immunology, La Jolla, CA, and approved February 12, 2020 (received for review August 12, 2019) Cytotoxic CD8+ T cells can effectively kill target cells by producing therefore developed a protocol that allowed for efficient iso- cytokines, chemokines, and granzymes. Expression of these effector lation of RNA and protein from fluorescence-activated cell molecules is however highly divergent, and tools that identify and sorting (FACS)-sorted fixed T cells after intracellular cytokine + preselect CD8 T cells with a cytotoxic expression profile are lacking. staining. With this top-down approach, we performed an un- + Human CD8 T cells can be divided into IFN-γ– and IL-2–producing biased RNA-sequencing (RNA-seq) and mass spectrometry cells. Unbiased transcriptomics and proteomics analysis on cytokine- γ– – + + (MS) analyses on IFN- and IL-2 producing primary human producing fixed CD8 T cells revealed that IL-2 cells produce helper + + + CD8 Tcells. -

Genetic Linkage Analysis

BASIC SCIENCE SEMINARS IN NEUROLOGY SECTION EDITOR: HASSAN M. FATHALLAH-SHAYKH, MD Genetic Linkage Analysis Stefan M. Pulst, MD enetic linkage analysis is a powerful tool to detect the chromosomal location of dis- ease genes. It is based on the observation that genes that reside physically close on a chromosome remain linked during meiosis. For most neurologic diseases for which the underlying biochemical defect was not known, the identification of the chromo- Gsomal location of the disease gene was the first step in its eventual isolation. By now, genes that have been isolated in this way include examples from all types of neurologic diseases, from neu- rodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer, Parkinson, or ataxias, to diseases of ion channels lead- ing to periodic paralysis or hemiplegic migraine, to tumor syndromes such as neurofibromatosis types 1 and 2. Arch Neurol. 1999;56:667-672 With the advent of new genetic markers tin gene, diagnosis using flanking mark- and automated genotyping, genetic map- ers requires the analysis of several family ping can be conducted extremely rap- members. idly. Genetic linkage maps have been gen- erated for the human genome and for LINKAGE OF GENES model organisms and have provided the basis for the construction of physical maps When Mendel observed an “independent that permit the rapid mapping of disease assortment of traits” (Mendel’s second traits. law), he was fortunate to have chosen traits As soon as a chromosomal location that were not localized close to one an- for a disease phenotype has been estab- other on the same chromosome.1 Subse- lished, genetic linkage analysis helps quent studies revealed that many genes determine whether the disease pheno- were indeed linked, ie, that traits did not type is only caused by mutation in a assort or segregate independently, but that single gene or mutations in other genes traits encoded by these linked genes were can give rise to an identical or similar inherited together. -

Role of RUNX1 in Aberrant Retinal Angiogenesis Jonathan D

Page 1 of 25 Diabetes Identification of RUNX1 as a mediator of aberrant retinal angiogenesis Short Title: Role of RUNX1 in aberrant retinal angiogenesis Jonathan D. Lam,†1 Daniel J. Oh,†1 Lindsay L. Wong,1 Dhanesh Amarnani,1 Cindy Park- Windhol,1 Angie V. Sanchez,1 Jonathan Cardona-Velez,1,2 Declan McGuone,3 Anat O. Stemmer- Rachamimov,3 Dean Eliott,4 Diane R. Bielenberg,5 Tave van Zyl,4 Lishuang Shen,1 Xiaowu Gai,6 Patricia A. D’Amore*,1,7 Leo A. Kim*,1,4 Joseph F. Arboleda-Velasquez*1 Author affiliations: 1Schepens Eye Research Institute/Massachusetts Eye and Ear, Department of Ophthalmology, Harvard Medical School, 20 Staniford St., Boston, MA 02114 2Universidad Pontificia Bolivariana, Medellin, Colombia, #68- a, Cq. 1 #68305, Medellín, Antioquia, Colombia 3C.S. Kubik Laboratory for Neuropathology, Massachusetts General Hospital, 55 Fruit St., Boston, MA 02114 4Retina Service, Massachusetts Eye and Ear Infirmary, Department of Ophthalmology, Harvard Medical School, 243 Charles St., Boston, MA 02114 5Vascular Biology Program, Boston Children’s Hospital, Department of Surgery, Harvard Medical School, 300 Longwood Ave., Boston, MA 02115 6Center for Personalized Medicine, Children’s Hospital Los Angeles, Los Angeles, 4650 Sunset Blvd, Los Angeles, CA 90027, USA 7Department of Pathology, Harvard Medical School, 25 Shattuck St., Boston, MA 02115 Corresponding authors: Joseph F. Arboleda-Velasquez: [email protected] Ph: (617) 912-2517 Leo Kim: [email protected] Ph: (617) 912-2562 Patricia D’Amore: [email protected] Ph: (617) 912-2559 Fax: (617) 912-0128 20 Staniford St. Boston MA, 02114 † These authors contributed equally to this manuscript Word Count: 1905 Tables and Figures: 4 Diabetes Publish Ahead of Print, published online April 11, 2017 Diabetes Page 2 of 25 Abstract Proliferative diabetic retinopathy (PDR) is a common cause of blindness in the developed world’s working adult population, and affects those with type 1 and type 2 diabetes mellitus. -

Pharmacological Mechanisms Underlying the Hepatoprotective Effects of Ecliptae Herba on Hepatocellular Carcinoma

Hindawi Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine Volume 2021, Article ID 5591402, 17 pages https://doi.org/10.1155/2021/5591402 Research Article Pharmacological Mechanisms Underlying the Hepatoprotective Effects of Ecliptae herba on Hepatocellular Carcinoma Botao Pan ,1 Wenxiu Pan ,2 Zheng Lu ,3 and Chenglai Xia 1,4 1Affiliated Foshan Maternity & Child Healthcare Hospital, Southern Medical University, Foshan 528000, China 2Department of Laboratory, Fifth People’s Hospital of Foshan, Foshan 528000, China 3Wuzhou Maternal and Child Health-Care Hospital, Wuzhou 543000, China 4School of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Southern Medical University, Guangzhou 510515, China Correspondence should be addressed to Zheng Lu; [email protected] and Chenglai Xia; [email protected] Received 30 January 2021; Revised 31 May 2021; Accepted 3 July 2021; Published 16 July 2021 Academic Editor: Hongcai Shang Copyright © 2021 Botao Pan et al. -is is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Background. -e number of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) cases worldwide has increased significantly. As a traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) with a long history, Ecliptae herba (EH) has been widely used in HCC patients in China, but its hepatoprotective mechanism is still unclear. Methods. In this study, we applied a network pharmacology-based strategy and experimental ver- ification to systematically unravel the underlying mechanisms of EH against HCC. First, six active ingredients of EH were screened from the Traditional Chinese Medicine Systems Pharmacology Database and Analysis Platform (TCMSP) by the ADME method. Subsequently, 52 potential targets of 6 active ingredients acting on HCC were screened from various databases, including TCMSP, DGIdb, SwissTargetPrediction, CTD, and GeneCards. -

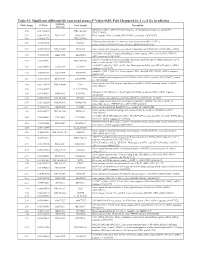

(P -Value<0.05, Fold Change≥1.4), 4 Vs. 0 Gy Irradiation

Table S1: Significant differentially expressed genes (P -Value<0.05, Fold Change≥1.4), 4 vs. 0 Gy irradiation Genbank Fold Change P -Value Gene Symbol Description Accession Q9F8M7_CARHY (Q9F8M7) DTDP-glucose 4,6-dehydratase (Fragment), partial (9%) 6.70 0.017399678 THC2699065 [THC2719287] 5.53 0.003379195 BC013657 BC013657 Homo sapiens cDNA clone IMAGE:4152983, partial cds. [BC013657] 5.10 0.024641735 THC2750781 Ciliary dynein heavy chain 5 (Axonemal beta dynein heavy chain 5) (HL1). 4.07 0.04353262 DNAH5 [Source:Uniprot/SWISSPROT;Acc:Q8TE73] [ENST00000382416] 3.81 0.002855909 NM_145263 SPATA18 Homo sapiens spermatogenesis associated 18 homolog (rat) (SPATA18), mRNA [NM_145263] AA418814 zw01a02.s1 Soares_NhHMPu_S1 Homo sapiens cDNA clone IMAGE:767978 3', 3.69 0.03203913 AA418814 AA418814 mRNA sequence [AA418814] AL356953 leucine-rich repeat-containing G protein-coupled receptor 6 {Homo sapiens} (exp=0; 3.63 0.0277936 THC2705989 wgp=1; cg=0), partial (4%) [THC2752981] AA484677 ne64a07.s1 NCI_CGAP_Alv1 Homo sapiens cDNA clone IMAGE:909012, mRNA 3.63 0.027098073 AA484677 AA484677 sequence [AA484677] oe06h09.s1 NCI_CGAP_Ov2 Homo sapiens cDNA clone IMAGE:1385153, mRNA sequence 3.48 0.04468495 AA837799 AA837799 [AA837799] Homo sapiens hypothetical protein LOC340109, mRNA (cDNA clone IMAGE:5578073), partial 3.27 0.031178378 BC039509 LOC643401 cds. [BC039509] Homo sapiens Fas (TNF receptor superfamily, member 6) (FAS), transcript variant 1, mRNA 3.24 0.022156298 NM_000043 FAS [NM_000043] 3.20 0.021043295 A_32_P125056 BF803942 CM2-CI0135-021100-477-g08 CI0135 Homo sapiens cDNA, mRNA sequence 3.04 0.043389246 BF803942 BF803942 [BF803942] 3.03 0.002430239 NM_015920 RPS27L Homo sapiens ribosomal protein S27-like (RPS27L), mRNA [NM_015920] Homo sapiens tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily, member 10c, decoy without an 2.98 0.021202829 NM_003841 TNFRSF10C intracellular domain (TNFRSF10C), mRNA [NM_003841] 2.97 0.03243901 AB002384 C6orf32 Homo sapiens mRNA for KIAA0386 gene, partial cds. -

Supplementary Figures and Tables

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA Supplementary Figure 1. Isolation and culture of endothelial cells from surgical specimens of FVM. (A) Representative pre-surgical fundus photograph of a right eye exhibiting a FVM encroaching on the optic nerve (dashed line) causing tractional retinal detachment with blot hemorrhages throughout retina (arrow heads). (B) Magnetic beads (arrows) allow for separation and culturing of enriched cell populations from surgical specimens (scale bar = 100 μm). (C) Cultures of isolated cells stained positively for CD31 representing a successfully isolated enriched population (scale bar = 40 μm). ©2017 American Diabetes Association. Published online at http://diabetes.diabetesjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.2337/db16-1035/-/DC1 SUPPLEMENTARY DATA Supplementary Figure 2. Efficient siRNA knockdown of RUNX1 expression and function demonstrated by qRT-PCR, Western Blot, and scratch assay. (A) RUNX1 siRNA induced a 60% reduction of RUNX1 expression measured by qRT-PCR 48 hrs post-transfection whereas expression of RUNX2 and RUNX3, the two other mammalian RUNX orthologues, showed no significant changes, indicating specificity of our siRNA. Functional inhibition of Runx1 signaling was demonstrated by a 330% increase in insulin-like growth factor binding protein-3 (IGFBP3) RNA expression level, a known target of RUNX1 inhibition. Western blot demonstrated similar reduction in protein levels. (B) siRNA- 2’s effect on RUNX1 was validated by qRT-PCR and western blot, demonstrating a similar reduction in both RNA and protein. Scratch assay demonstrates functional inhibition of RUNX1 by siRNA-2. ns: not significant, * p < 0.05, *** p < 0.001 ©2017 American Diabetes Association. Published online at http://diabetes.diabetesjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.2337/db16-1035/-/DC1 SUPPLEMENTARY DATA Supplementary Table 1. -

Genetic Linkage of the Huntington's Disease Gene to a DNA Marker James F

LE JOURNAL CANADIEN DES SCIENCES NEUROLOG1QUES SPECIAL FEATURE Genetic Linkage of the Huntington's Disease Gene to a DNA Marker James F. Gusella ABSTRACT: Recombinant DNA techniques have provided the means to generate large numbers of new genetic linkage markers. This technology has been used to identify a DNA marker that coinherits with the Huntington's Disease (HD) gene in family studies. The HD locus has thereby been mapped to human chromosome 4. The discovery of a genetic marker for the inheritance of HD has implications both for patient care and future research. The same approach holds considerable promise for the investigation of other genetic diseases, including Dystonia Musculorum Deformans. RESUME: Les techniques d'ADN recombine ont fourni le moyen de g£nerer un grand nombre de nouveux marqueurs a liason g6n£tique. Cette technologie a He employe" afin d'identifier un marqueur d'ADN qui co-herite avec le gene de la maladie de Huntington (MH) dans les etudes familiales. Le lieu du gene de la MH a ainsi 6te localise sur le chromosome humain numero 4. La d6couverte d'un marqueur g6n6tique pour I'her6dit6 de MH a des implications pour la soin de patients ainsi que pour la recherche dans le futur. La meme approche semble pleine de promesses pour l'investigation d'autres maladies g6ndtiques, incluant la dystonie musculaire deTormante. Can. J. Neurol. Sci. 1984; 11:421-425 Huntington's Disease currently no effective therapy to cure this devastating disease, Huntington's disease (HD) is a genetic neurodegenerative or to slow its inexorable progression. disorder first described by George Huntington in 1873 (Hunting ton, 1972;Hayden, 1981;Chaseetal., 1979). -

A DNA Methylation Biomarker of Alcohol Consumption

OPEN Molecular Psychiatry (2018) 23, 422–433 www.nature.com/mp ORIGINAL ARTICLE A DNA methylation biomarker of alcohol consumption C Liu1,2,3,55, RE Marioni4,5,6,55, ÅK Hedman7,55, L Pfeiffer8,9,55, P-C Tsai10,55, LM Reynolds11,55, AC Just12,55, Q Duan13,55, CG Boer14,55, T Tanaka15,55, CE Elks16, S Aslibekyan17, JA Brody18, B Kühnel8,9, C Herder19,20, LM Almli21, D Zhi22, Y Wang23, T Huan1,2,CYao1,2, MM Mendelson1,2, R Joehanes1,2,24, L Liang25, S-A Love23, W Guan26, S Shah6,27, AF McRae6,27, A Kretschmer8,9, H Prokisch28,29, K Strauch30,31, A Peters8,9,32, PM Visscher4,6,27,NRWray6,27, X Guo33, KL Wiggins18, AK Smith21, EB Binder34, KJ Ressler35, MR Irvin17, DM Absher36, D Hernandez37, L Ferrucci15, S Bandinelli38, K Lohman11, J Ding39, L Trevisi40, S Gustafsson7, JH Sandling41,42, L Stolk14, AG Uitterlinden14,43,IYet10, JE Castillo-Fernandez10, TD Spector10, JD Schwartz44, P Vokonas45, L Lind46,YLi47, M Fornage48, DK Arnett49, NJ Wareham16, N Sotoodehnia18, KK Ong16, JBJ van Meurs14, KN Conneely50, AA Baccarelli51, IJ Deary4,52, JT Bell10, KE North23,56, Y Liu11,56, M Waldenberger8,9,56, SJ London53,56, E Ingelsson7,54,56 and D Levy1,2,56 The lack of reliable measures of alcohol intake is a major obstacle to the diagnosis and treatment of alcohol-related diseases. Epigenetic modifications such as DNA methylation may provide novel biomarkers of alcohol use. To examine this possibility, we performed an epigenome-wide association study of methylation of cytosine-phosphate-guanine dinucleotide (CpG) sites in relation to alcohol intake in 13 population-based cohorts (ntotal = 13 317; 54% women; mean age across cohorts 42–76 years) using whole blood (9643 European and 2423 African ancestries) or monocyte-derived DNA (588 European, 263 African and 400 Hispanic ancestry) samples. -

Linkage & Genetic Mapping in Eukaryotes

LinLinkkaaggee && GGeenneetticic MMaappppiningg inin EEuukkaarryyootteess CChh.. 66 1 LLIINNKKAAGGEE AANNDD CCRROOSSSSIINNGG OOVVEERR ! IInn eeuukkaarryyoottiicc ssppeecciieess,, eeaacchh lliinneeaarr cchhrroommoossoommee ccoonnttaaiinnss aa lloonngg ppiieeccee ooff DDNNAA – A typical chromosome contains many hundred or even a few thousand different genes ! TThhee tteerrmm lliinnkkaaggee hhaass ttwwoo rreellaatteedd mmeeaanniinnggss – 1. Two or more genes can be located on the same chromosome – 2. Genes that are close together tend to be transmitted as a unit Copyright ©The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. Permission required for reproduction or display 2 LinkageLinkage GroupsGroups ! Chromosomes are called linkage groups – They contain a group of genes that are linked together ! The number of linkage groups is the number of types of chromosomes of the species – For example, in humans " 22 autosomal linkage groups " An X chromosome linkage group " A Y chromosome linkage group ! Genes that are far apart on the same chromosome can independently assort from each other – This is due to crossing-over or recombination Copyright ©The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. Permission required for reproduction or display 3 LLiinnkkaaggee aanndd RRecombinationecombination Genes nearby on the same chromosome tend to stay together during the formation of gametes; this is linkage. The breakage of the chromosome, the separation of the genes, and the exchange of genes between chromatids is known as recombination. (we call it crossing over) 4 IndependentIndependent assortment:assortment: