Music and Identity: the Eritrean Diaspora in London1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kennington Parkpark Thethe Birthplacebirthplace Ofof People’Speople’S Democracydemocracy

KenningtonKennington ParkPark TheThe BirthplaceBirthplace ofof People’sPeople’s DemocracyDemocracy StefanStefan SzczelkunSzczelkun KenningtonKennington ParkPark TheThe BirthplaceBirthplace ofof People’sPeople’s DemocracyDemocracy StefanStefan SzczelkunSzczelkun past tense Published by past tense Originally published 1997. Second edition 2005. This (third) edition 2018. past tense c/o 56a Infoshop 56 Crampton Street, London. SE17 3AE email: [email protected] More past tense texts and other material can be f ound at http://www.past-tense.org.uk http://pasttenseblog.wordpress.com https: twitter.com/@_pasttense_ https: www.facebook.com/pastensehistories The Birthplace of People’s Democracy A short one hundred and fifty years ago Kennington Common, later to be renamed Kennington Park, was host to a historic gathering which can now be seen as the birth of modern British democracy. In reaction to this gathering, the great Chartist rally of 10th April 1848, the common was forcibly enclosed and the Victorian Park was built to occupy the site. History is not objective truth. It is a selection of some facts from a mass of evidences to construct a particular view, which inevitably, reflects the ideas of the historian and their social milieu. The history most of us learnt in school left out the stories of most of the people who lived and made that history. If the design of the Victorian park means anything it is a negation of such a people’s history: an enforced amnesia of what the real Kennington Common, looking South, in 1839. On the right is the Horns Tavern; in the distance on the left is St. Marks Church. 1 importance of this space is about. -

Joining Papers 2 December 2014 Kia Oval, London London Development Conference 2014 Solving the City’S Housing Crisis

Tuesday Joining papers 2 December 2014 Kia Oval, London London Development Conference 2014 Solving the City’s housing crisis 1. Debate the opportunities and challenges in the London development market, from the practical to the visionary with over 200 other housing professionals 2. Hear high quality content led by London’s most reputable housing experts and policy makers including local authority councillors, MPs, regulators and representatives from visionary housing associations 3. Get an insight into what the future may bring with the 2016 London mayoral election Book your place at www.housing.org.uk/events @natfedevents call 020 7067 1066 email [email protected] #NHFDevelop JOINING INSTRUCTIONS The information provided in this document will help you get the most out of your time at the event. Please bring these instructions with you on the day, along with your confirmation letter, as they will help ensure you have a smooth arrival. VENUE DETAILS Kia Oval (Alec Stewart Gate) Kennington London SE11 5SS Tel: 0844 375 1845 Web: www.kiaoval.com TRAVEL DETAILS Full location and travel details can be found here: http://www.kiaoval.com/contact-us/getting-to-the- kia-oval/ By train: The nearest railway stations are Oval, which is a five minute walk and Vauxhall which is a twelve minute walk to Kia Oval. By underground: Take the Northern Line to the Oval tube station. The main entrance to the ground is 100 metres on your left on leaving the station. The ground is also a ten minute walk from Vauxhall tube station which is on the Victoria line. -

Report on Minority Groups in Somalia

The Danish Immigration Service Ryesgade 53 DK-2100 Copenhagen Ø Phone: + 45 35 36 66 00 Website: www.udlst.dk E-mail: [email protected] Report on minority groups in Somalia Joint British, Danish and Dutch fact-finding mission to Nairobi, Kenya 17 – 24 September 2000 Report on minority groups in Somalia Table of contents 1. Background ..................................................................................................................................5 2. Introduction to sources and methodology....................................................................................6 3. Overall political developments and the security situation in Somalia.......................................10 3.1 Arta peace process in Djibouti...............................................................................................10 3.2 Transitional National Assembly (TNA) and new President ..................................................10 3.2.1 Position of North West Somalia (Somaliland)...............................................................12 3.2.2 Position of North East Somalia (Puntland)....................................................................13 3.2.3 Prospects for a central authority in Somalia ..................................................................13 3.3 Security Situation...................................................................................................................14 3.3.1 General...........................................................................................................................14 -

Road Modernisation Plan the Biggest Road Investment Programme for a Generation

London’s Road Modernisation Plan The biggest road investment programme for a generation Paul, Cindy, Toyin, Ikenna, Rakhi, Transport for London Foreword London is the engine of the British economy, This is a continual challenge in a city with a road and it is set to grow by almost two million network that was never designed to cater for people by 2031. That’s the equivalent of so much traffi c. We need to respond to these absorbing the populations of Birmingham changes and ensure our road network, and the and Leeds. It also means that an extra fi ve way we manage it, is fi t for a world city in the million daily trips, on top of the 26 million 21st century. trips that already happen every day, will take place by 2030. That is why we have planned an unprecedented programme of road improvements. Our Road This population growth is fuelling a boom Modernisation Plan is an integrated response to in property investment and development the way London is changing and growing, looking resulting in more homes, shops, public spaces to create better places, better cycling routes, and workplaces. At the same time, Londoners safer streets and more reliable journeys. It will and businesses have growing expectations help London cope with a growing population and of the quality of the streets where they live create hundreds of thousands of new jobs and and work. All of this affects the way our homes so we can remain one of the most vibrant, roads operate. accessible and competitive cities in the world. -

Two Bed Properties Looking for Larger

Two Bed Properties Looking for Larger MX REF ADDRESS PROPERTY TYPE PROPERTY DETAILS WANT AREA SPECIAL REQUIREMENTS Brixton, Newark House, Loughborough Kennington, OC315-2B Council Flat 2nd floor flat: no lift 3 Road, London, SW9 7SH Norwood, Oval, Tulse Hill Ground floor house conversion street property that is not on an estate. Biggest bedroom has French doors out to garden, which we have exclusive use of. Good Anywhere in OC163-2B Mervan Road, London, SW2 1DT Council Flat 3 size property, with big front room and main Lambeth bedroom. In good state of decoration, basement storage space, very close to Brixton. Clapham, Maisonette in a good location near clapham common OC282-2B Cedars Road, London, SW4 0PY Council Maisonette 3 Streatham or station and park, has a balcony Stockwell Streatham, 4th floor flat with balcony, off street parking, estate Clapham William Bonney Estate, London, OC189-2B Council Flat parking, close to shops & clapham common/north 3 Common, Tulse Ground or first floor only SW4 7JQ tube station. Hill, West Norwood Fairford House, Kennington Lane, 5th floor flat with lift, balcony, garage, refurbished Anywhere in OC172-2B Council Flat 3 London, SE11 4HW kitchen and bathroom, big spacy rooms Lambeth • Brixton 10th floor flat. 2 double rooms. Long balcony with an • Clapham amazing view that looks out over Battersea, friendly, • North Amesbury Tower, Wandsworth quiet area. Close to overground and various stores. OC985-2B Council Flat 3 Lambeth Road, London, SW8 3LG Bathroom, Kitchn & front door refurbished recently. • Stockwell Two working lifts. 24/7 Security. Parking also and Vassall available. • Streatham Ground floor flat, both double rooms. -

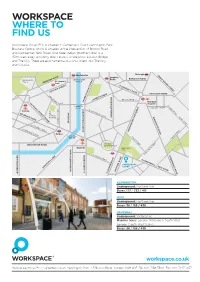

Workspace Where to Find Us

Workspace Where to Find us Workspace Group PLC is situated in Canterbury Court, Kennington Park Business Centre, which is situated at the intersection of Brixton Road and Camberwell New Road. Oval tube station (Northern line) is a 150m walk away providing direct access to Waterloo, London Bridge and The City. There are also numerous bus links direct into The City and Victoria. Borough Westminster GREAT DOVER STREET Lambeth BOROUGH ROAD Buckingham WESTMINSTER North Palace St. James’s BRIDGE BIRDCAGE WALKPark ST. GEORGE’S ROAD VICTORIA STREET NEW KENT ROAD HORSEFERRY LAMBETH ROAD BROOK DRIVE LAMBETH PALACE ROAD Elephant VAUXHALL BRIDGE ROAD ROAD & Castle RODNEY ROAD LAMBETH BRIDGE HAYGATE STREET BLACK PRINCES ROAD Victoria BELGRAVE ROAD The Gordon WALWORTH ROAD Hospital ROAD KENNINGTON FLINT STREET MILLBANK REGENCY STREET REGENCY ST. GEORGE’S DRIVE SUTHERLAND STREET KENNINGTON PARK ROAD ALBERT EMBANKMENT ALBERT Pimlico VAUXHALL COOK’S ROAD BRIDGE ALBANY ROAD The Oval GROSVENOR ROAD Cricket Ground Vauxhall Kennington Park FENTIMAN ROAD JON RUSKIN STREET CAMBERWELL ROAD CAMBERWELL NEW ROAD CANTERBURY COURT NINE ELM’S LANE WANDSWORTH ROAD WANDSWORTH BRIXTON ROAD S LAMBETH ROAD QUEENSTOWN RD QUEENSTOWN CLAPHAM ROAD kennington Underground: Northern line Buses: 133 / 333 / 415 oval Underground: Northern line Buses: 36 / 185 / 436 vauxhall Underground: Victoria line Mainline trains: London Waterloo & South West London (South West trains) Buses: 36 / 185 / 436 workspace.co.uk Workspace Group PLC Canterbury Court Kennington Park 1–3 Brixton Road London SW9 6DE Tel: 020 7138 3300 Fax: 020 7247 0157. -

Tuberculosis in London: Annual Review (2013 Data)

Tuberculosis in London: Annual review (2013 data) Data from 1999 to 2013 Tuberculosis in London (2013) About Public Health England Public Health England exists to protect and improve the nation's health and wellbeing, and reduce health inequalities. It does this through world-class science, knowledge and intelligence, advocacy, partnerships and the delivery of specialist public health services. PHE is an operationally autonomous executive agency of the Department of Health. Public Health England Wellington House 133-155 Waterloo Road London SE1 8UG Tel: 020 7654 8000 http://www.gov.uk/phe Twitter: @PHE_uk Facebook: www.facebook.com/PublicHealthEngland Prepared by: Field Epidemiology Services (Victoria) For queries relating to this document, please contact: [email protected] © Crown copyright 2014 You may re-use this information (excluding logos) free of charge in any format or medium, under the terms of the Open Government Licence v2.0. To view this licence, visit OGL or email [email protected]. Where we have identified any third party copyright information you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned. Any enquiries regarding this publication should be sent to [email protected]. Published October 2014 PHE gateway number: 2014448 This document is available in other formats on request. Please call 020 8327 7018 or email [email protected] Tuberculosis in London (2013) Contents About Public Health England 2 Contents 2 Executive summary 5 Background 8 Objectives 8 Tuberculosis -

Eritrea: Fact-Finding Mission to Ethiopia

ERITREA: FACT-FINDING MISSION TO ETHIOPIA IN MAY 2019 20.11.2019 Fact-finding Mission Report Country Information Service Raportti MIG-205841 06.03.00 07.04.2020 MIGDno-2019-205 Introduction This report has been prepared as part of the FAKTA project, which has received funding from the European Union’s Asylum, Migration and Integration Fund (AMIF).1 Researchers of the Finnish Immigration Service’s Country Information Service conducted a fact-finding mission regarding Eritrea to Ethiopia in May 2019. The purpose of the fact-finding mission was to gather information on the effects of the peace agreement between Eritrea and Ethiopia, the situation at the border between Eritrea and Ethiopia, and the situation of Eritrean refugees in Ethiopia. Another objective of the mission was to create a contact network with international and national operators. During the fact-finding mission, the researchers visited the Tigray Region near the border with Eritrea, and the capital city of Addis Ababa. The researchers interviewed international organisations and Ethiopian operators as well as Eritrean refugees and asylum seekers who had arrived in Ethiopia. The parties interviewed for this report did not want their names revealed in the report, due to the sensitive nature of the subject matter. Some of the interviewees wished to remain completely anonymous. 1 Development Project for fact-finding mission practices on country of origin information 2017–2020. PL 10 PB 10 PO Box 10 00086 Maahanmuuttovirasto 00086 Migrationsverket FI-00086 Maahanmuuttovirasto puh. 0295 430 431 tfn 0295 430 431 tel. +358 295 430 431 faksi 0295 411 720 fax 0295 411 720 fax +358 295 411 720 2 (52) Contents 1 The effects of the peace agreement between Ethiopia and Eritrea in Eritrea ......................... -

Spectral Latinidad: the Work of Latinx Migrants and Small Charities in London

The London School of Economics and Political Science Spectral Latinidad: the work of Latinx migrants and small charities in London Ulises Moreno-Tabarez A thesis submitted to the Department of Geography and Environment of the London School of Economics for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, London, December 2018 Declaration I certify that the thesis I have presented for examination for the MPhil/PhD degree of the London School of Economics and Political Science is solely my own work other than where I have clearly indicated that it is the work of others (in which case the extent of any work carried out jointly by me and any other person is clearly identified in it). The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. Quotation from it is permitted, provided that full acknowledgement is made. This thesis may not be reproduced without my prior written consent. I warrant that this authorisation does not, to the best of my belief, infringe the rights of any third party. I declare that my thesis consists of 93,762 words. Page 2 of 255 Abstract This thesis asks: what is the relationship between Latina/o/xs and small-scale charities in London? I find that their relationship is intersectional and performative in the sense that political action is induced through their interactions. This enquiry is theoretically guided by Derrida's metaphor of spectrality and Massey's understanding of space. Derrida’s spectres allow for an understanding of space as spectral, and Massey’s space allows for spectres to be understood in the context of spatial politics. -

Institutionalising Diaspora Linkage the Emigrant Bangladeshis in Uk and Usa

Ministry of Expatriates’ Welfare and Overseas Employmwent INSTITUTIONALISING DIASPORA LINKAGE THE EMIGRANT BANGLADESHIS IN UK AND USA February 2004 Ministry of Expatriates’ Welfare and Overseas Employment, GoB and International Organization for Migration (IOM), Dhaka, MRF Opinions expressed in the publications are those of the researchers and do not necessarily reflect the views of the International Organization for Migration. IOM is committed to the principle that humane and orderly migration benefits migrants and society. As an inter-governmental body, IOM acts with its partners in the international community to: assist in meeting the operational challenges of migration; advance understanding of migration issues; encourage social and economic development through migration; and work towards effective respect of the human dignity and well-being of migrants. Publisher International Organization for Migration (IOM), Regional Office for South Asia House # 3A, Road # 50, Gulshan : 2, Dhaka : 1212, Bangladesh Telephone : +88-02-8814604, Fax : +88-02-8817701 E-mail : [email protected] Internet : http://www.iow.int ISBN : 984-32-1236-3 © [2002] International Organization for Migration (IOM) Printed by Bengal Com-print 23/F-1, Free School Street, Panthapath, Dhaka-1205 Telephone : 8611142, 8611766 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise without prior written permission of the publisher. -

October 2015 No.219, Quarterly, Free to Members

THE BRIXTON SOCIETY NEWSLETTER Autumn, October 2015 No.219, quarterly, free to members. Registered with the London Forum of Amenity Societies, Registered Charity No.1058103, Website: www.brixtonsociety.org.uk Welcome from the Editor It’s catch-up time again for those who have not been able to get to every meeting or event that we have highlighted. Following on from September’s Lambeth Heritage Festival, we have given more space to local history topics in this issue. However, there are still some big Regeneration issues continuing to trouble us. Pop Brixton hosted the launch of the Brixton Due to this being compiled and distributed in Design Trail last month, marking Brixton’s various members’ spare time, unavoidable involvement in the London Design Festival, absences mean this will reach most of you a which we hope will develop. (BDT-15-01.jpg) week later than usual. By then Lambeth’s Cabinet should have agreed a way forward on There’s still time to discover its Culture 2020 package. At the time of writing, only the Library proposals had been Lambeth’s Hidden River! unveiled, with the future of parks, recreation Lambeth Heritage Festival month has now centres and arts still unclear. Of course you passed, but there’s just time to catch the can get more frequent updates from our exhibition at the Morley Gallery in website and – if you supply me with an e-mail Westminster Bridge Road SE1, until Friday 23 address – occasional internet bulletins. October (11 am to 6 pm, closed Sundays). Space permitting, we try to feature local events It features Lambeth’s Thames riverside over and publish reminiscences or enquiries in our time, and also illustrates the full length of the newsletter. -

Download Full Publication

Pau[ Iganski Vicky Kielinger Susan Paterson 5*r KEY FINDINGS 1 KEY FINDINGS Trends in antisemitic incidents · The number of incidents recorded by the Metropolitan Police Service (MPS) each month fluctuates. Peaks are commonly attributed to international political events, and especially conflicts in the Middle East and flare-ups in the Israeli–Palestinian conflict. Troughs indicate a pos- sible seasonal trend. · An early upward trend in recorded incidents between 1996 and 2000 may reflect a real increase in incidents, but it may be wholly or partly an artefact resulting from devel- opments in the policing of antisemitic crime by the MPS. · A downward trend in incidents since 2001 is evident, but it cannot be concluded from the police data alone whether this represents an actual decline in victimisation, espe- cially as it runs counter to the trend recorded by the Community Security Trust (CST). · Racist incidents recorded by the MPS from January 2001 to December 2004 also show a downward trend in the frequency of incidents across the four years. · An analysis of a sub-sample of antisemitic incidents re- corded by the MPS suggests that many incidents appear to be opportunistic and indirect in nature. 1 HATE CRIMES AGAINST LONDON’S JEWS Location of antisemitic incidents · One-third of antisemitic incidents are recorded as occur- ring in the London Borough of Barnet. This matches the proportion of London’s Jewish population that live in the borough. Incidents reported in Barnet, Hackney, Westminster and Camden account for just under two- thirds of all incidents reported. · Most incidents occur either at identifiably Jewish locations (such as places of worship and schools) or in public loca- tions where the victims are identifiably Jewish.