University of Cincinnati

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Rosenwinkel Introductions

The Rosenwinkel Introductions: Stylistic Tendencies in 10 Introductions Recorded by Jazz Guitarist Kurt Rosenwinkel Jens Hoppe A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of requirements for the degree of Master of Music (Performance) Conservatorium of Music University of Sydney 2017 Declaration I, Jens Hoppe, hereby declare that this submission is my own work and that it contains no material previously published or written by another person except where acknowledged in the text. This thesis contains no material that has been accepted for the award of a higher degree. Signed: ______________________________________________Date: 31 March 2016 i Acknowledgments The task of writing a thesis is often made more challenging by life’s unexpected events. In the case of this thesis, it was burglary, relocation, serious injury, marriage, and a death in the family. Disruptions also put extra demands on those surrounding the writer. I extend my deepest gratitude to the following people for, above all, their patience and support. To my supervisor Phil Slater without whom this thesis would not have been possible – for his patience, constructive comments, and ability to say things that needed to be said in a positive and encouraging way. Thank you Phil. To Matt McMahon, who is always an inspiration, whether in conversation or in performance. To Simon Barker, for challenging some fundamental assumptions and talking about things that made me think. To Troy Lever, Abel Cross, and Pete ‘Göfren’ for their help in the early stages. They are not just wonderful musicians and friends, but exemplary human beings. To Fletcher and Felix for their boundless enthusiasm, unconditional love and the comic relief they provided. -

The Form of the Preludes to Bach's Unaccompanied Cello Suites

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014 2011 The orF m of the Preludes to Bach's Unaccompanied Cello Suites Daniel E. Prindle University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/theses Part of the Composition Commons, Musicology Commons, Music Practice Commons, and the Music Theory Commons Prindle, Daniel E., "The orF m of the Preludes to Bach's Unaccompanied Cello Suites" (2011). Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014. 636. Retrieved from https://scholarworks.umass.edu/theses/636 This thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE FORM OF THE PRELUDES TO BACH’S UNACCOMPANIED CELLO SUITES A Thesis Presented by DANIEL E. PRINDLE Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts Amherst in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF MUSIC May 2011 Master of Music in Music Theory © Copyright by Daniel E. Prindle 2011 All Rights Reserved ii THE FORM OF THE PRELUDES TO BACH’S UNACCOMPANIED CELLO SUITES A Thesis Presented by DANIEL E. PRINDLE Approved as to style and content by: _____________________________________ Gary Karpinski, Chair _____________________________________ Miriam Whaples, Member _____________________________________ Brent Auerbach, Member ___________________________________ Jeffrey Cox, Department Head Department of Music and Dance iii DEDICATION To Michelle and Rhys. iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First and foremost, I would like to acknowledge the generous sacrifice made by my family. -

J. S. BACH English Suites Nos

J. S. BACH English Suites Nos. 4–6 Arranged for Two Guitars Montenegrin Guitar Duo Johann Sebastian Bach (1685–1750) with elegantly broken chords. This is interrupted by a The contrasting pair of Gavottes with a perky walking bass English Suites Nos. 4–6, BWV 809–811 sudden burst of semiquavers leading to a moment’s accompaniment brings in the atmosphere of a pastoral reflection before plunging into an extended and brilliant dance in the market square. The second Gavotte evokes (Arranged for two guitars by the Montenegrin Guitar Duo) fugal Allegro. Of the Préludes in the English Suites this is images of wind instruments piping together in rustic chorus. The English Suites is the title given to a set of six suites for Bach scholar, David Schulenberg has observed that while the longest and most elaborate. The Allemande which The Gigue, in 12/16 metre, is virtuosic in both keyboard believed to have been composed between 1720 the beginning of the Gigue presents a normal three-part follows is, in comparison, an oasis of calm, with superb compositional aspects and the technical demands on the and the early 1730s. During this period, Bach also explored fugal exposition, from then on, no more than two voices are contrapuntal writing and ingenious tonal modulations. The performers. Bach’s incomparable art of fugal writing is at the suite form in the six French Suites and the seven large heard at a time. Courante unites a French-style melodic line with a full stretch here, the second half representing, as in mirror suites under the title of Partitas (six in all) and an English Suite No. -

Further Considerations of the Continuous ^5 with an Introduction and Explanation of Schenker's Five Interruption Models

Further Considerations of the Continuous ^5 with an Introduction and Explanation of Schenker's Five Interruption Models By: Irna Priore ―Further Considerations about the Continuous ^5 with an Introduction and Explanation of Schenker’s Five Interruption Models.‖ Indiana Theory Review, Volume 25, Spring-Fall 2004 (spring 2007). Made available courtesy of Indiana University School of Music: http://www.music.indiana.edu/ *** Note: Figures may be missing from this format of the document Article: Schenker’s works span about thirty years, from his early performance editions in the first decade of the twentieth century to Free Composition in 1935.1 Nevertheless, the focus of modern scholarship has most often been on the ideas contained in this last work. Although Free Composition is indeed a monumental accomplishment, Schenker's early ideas are insightful and merit further study. Not everything in these early essays was incorporated into Free Composition and some ideas that appear in their final form in Free Composition can be traced back to his previous writings. This is the case with the discussion of interruption, a term coined only in Free Composition. After the idea of the chord of nature and its unfolding, interruption is probably the most important concept in Free Composition. In this work Schenker studied the implications of melodic descent, referring to the momentary pause of this descent prior to the achievement of tonal closure as interruption. In his earlier works he focused more on the continuity of the line itself rather than its tonal closure, and used the notion of melodic line or melodic continuity to address long-range connections. -

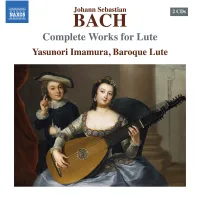

Imamura-Y-S03c[Naxos-2CD-Booklet

573936-37 bk Bach EU.qxp_573936-37 bk Bach 27/06/2018 11:00 Page 2 CD 1 63:49 CD 2 53:15 CD 2 Arioso from St John Passion, BWV 245 1Partita in E major, BWV 1006a 20:41 1Suite in E minor, BWV 996 18:18 # # Prelude 2:51 Consider, O my soul 2 Prelude 4:13 2 Betrachte, meine Seel’ Allemande 3:02 3 Loure 3:58 3 Betrachte, meine Seel’, mit ängstlichem Vergnügen, Consider, O my soul, with fearful joy, consider, Courante 2:40 4 Gavotte en Rondeau 3:29 4 Mit bittrer Lust und halb beklemmtem Herzen in the bitter anguish of thy heart’s affliction, Sarabande 4:24 5 Menuet I & II 4:43 5 Dein höchstes Gut in Jesu Schmerzen, thy highest good is Jesus’ sorrow. Bourrée 1:33 6 Bourrée 1:51 6 Wie dir auf Dornen, so ihn stechen, For thee, from the thorns that pierce Him, Gigue 2:27 Gigue 3:48 Die Himmelsschlüsselblumen blühn! what heavenly flowers spring. Du kannst viel süße Frucht von seiner Wermut brechen Thou canst the sweetest fruit from his wormwood gather, 7Suite in C minor, BWV 997 22:01 7Suite in G minor, BWV 995 25:15 Drum sieh ohn Unterlass auf ihn! then look on Him for evermore. Prelude 6:11 8 Prelude 3:11 8 Allemande 6:18 9 Fugue 7:13 9 Sarabande 5:28 0 Courante 2:35 Recitativo from St Matthew Passion, BWV 244b 0 $ $ Gigue & Double 6:09 ! Sarabande 2:50 Gavotte I & II 4:43 Ja freilich will in uns Yes! Willingly will we ! @ Prelude in C minor, BWV 999 1:55 Gigue 2:38 Ja freilich will in uns das Fleisch und Blut Yes! Willingly will we, Flesh and blood, Zum Kreuz gezwungen sein; Be brought to the cross; @ Fugue in G minor, BWV 1000 5:46 #Arioso from St John Passion, BWV 245 2:24 Je mehr es unsrer Seele gut, The harsher the pain Arioso: Betrachte, meine Seel’ Je herber geht es ein. -

Southern California Junior Bach Festival

The SCJBF 3 year, cyclical repertoire list for the Complete Works Audition Students may enter the Complete Works Audition (CWA) only once each year as a soloist on the same instrument and must perform the same music in the same category that they performed at the Branch and Regional Festivals, but complete as indicated on this list. Students will be disqualified if photocopied music is presented to the judges or used by accompanists (with the exception of facilitating page turns). Note: Repertoire lists for years in parentheses are not finalized and are subject to change Category I – SHORT PRELUDES AND FUGUES Year Composition BWV Each year Select any two of the following: Preludes: BWV 924-943 and 999 Fugues: BWV 952, 953 and 961 Select one of the following: 1. Prelude and Fugue in a m 895 2. Prelude and Fughetta in d m 899 3. Prelude and Fugue in e m 900 4. Prelude and Fughetta in G M 902 Category II – VARIOUS DANCE MOVEMENTS The dance movements listed below – from one of the listed Suites or Partitas – are required for the Complete Works Audition. Year Composition BWV 2021 English Suites: 1. From the A Major #1 806 The Bourree I and the Bourree II 2. From the e minor #5 810 The Passepied I and the Passepied II French Suites: 1. From the d minor #1 812 The Menuet I and the Menuet II 2. From the G Major #5 816 The Gavotte, Bourree and Loure Partitas: 1. From the a min or #3 827 The Burlesca and the Scherzo 2. -

Raff's Arragement for Piano of Bach's Cello Suites

Six Sonatas for Cello by J.S.Bach arranged for the Pianoforte by JOACHIM RAFF WoO.30 Sonata No.1 in G major Sonate No.2 in D minor Sonate No.3 in C major Sonate No.4 in E flat major Sonate No.5 in C minor Sonate No.6 in D major Joachim Raff’s interest in the works of Johann Sebastian Bach and the inspiration he drew from them is unmatched by any of the other major composers in the second half of the 19th century. One could speculate that Raff’s partiality for polyphonic writing originates from his studies of Bach’s works - the identification of “influenced by Bach” with “Polyphony” is a popular idea but is often questionable in terms of scientific correctness. Raff wrote numerous original compositions in polyphonic style and used musical forms of the baroque period. However, he also created a relatively large number of arrangements and transcriptions of works by Bach. Obviously, Bach’s music exerted a strong attraction on Raff that went further than plain admiration. Looking at Raff’s arrangements one can easily detect his particular interest in those works by Bach that could be supplemented by another composer. Upon these models Raff could fit his reverence for the musical past as well as exploit his never tiring interest in the technical aspects of the art of composition. One of the few statements we have by Raff about the basics of his art reveal his concept of how to attach supplements to works by Bach. Raff wrote about his orchestral arrangement of Bach’s Ciaconna in d minor for solo violin: "Everybody who has studied J.S. -

Pieter Wispelwey, Cello Caroline Almonte, Piano

PIETER WISPELWEY PIETER WISPELWEY, CELLO CAROLINE ALMONTE, PIANO BEETHOVEN WEDNESDAY 16 AUGUST 7pm Elisabeth Murdoch Hall with Caroline Almonte, piano 6.15pm free pre-concert talk with Zoe Knighton DURATION: Three hours with one 20-minute interval and a second 15-minute interval BACH 3 THURSDAY 17 AUGUST 7pm Elisabeth Murdoch Hall 6.15pm free pre-concert talk with Zoe Knighton DURATION: Three hours with one 20-minute interval and a second 10-minute interval BRAHMS FRIDAY 18 AUGUST 7pm Elisabeth Murdoch Hall with Caroline Almonte, piano 6.15pm free pre-concert talk with Zoe Knighton DURATION: One hour & 35-minutes with one 20-minute interval These concerts are being recorded by ABC Classic FM as part of a live-to-air broadcast. Melbourne Recital Centre acknowledges the people of the Kulin nation on whose land this concert is being presented. ELISABETH MURDOCH HALL GREAT•PERFORMERS•••••••2017 Photo: John Gollings PIETER WISPELWEY WELCOME EUAN MURDOCH, CEO Wominjeka, welcome to this On behalf of everyone gathered extraordinary trio of concerts by one in Elisabeth Murdoch Hall tonight, 5 of the world’s greatest cellists, Pieter I extend our appreciation to Pieter Wispelwey. He’s simply one of the most and Caroline for sharing this wonderful interesting musicians on the scene, music with us. Thank you to the Legal with a curiosity and wit to match his Friends of Melbourne Recital Centre formidable technical facility. for their generous support of these concerts as the Great Performers Over three nights we’ll hear the Series Partner, thanks also to members complete cello and piano works of the Great Performers Leadership of Beethoven and Brahms, with Circle and The Langham, a longterm Melbourne-based pianist Caroline partner of the program. -

Understanding Ornamentation in Atonal Music Michael Buchler College of Music, Florida State University, U.S.A

Understanding Ornamentation in Atonal Music Michael Buchler College of Music, Florida State University, U.S.A. [email protected] ABSTRACT # j E X. X E In 1987, Joseph Straus convincingly argued that prolongational & E claims were unsupportable in post-tonal music. He also, intentionally or not, set the stage for a slippery slope argument whereby any small E # E E E morsel of prolongationally conceived structure (passing tones, ? E neighbor tones, suspensions, and the like) would seem just as Example 1. An escape tone that is not “non-harmonic.” problematic as longer-range harmonic or melodic enlargements. Prolongational structures are hierarchical, after all. This paper argues Example 2 excerpts an oft-contemplated piece: that large-scale prolongations are inherently different from Schoenberg’s op. 19, no. 6. In mm. 3-4, E6, the highest note small-scale ones in atonal (and possibly also tonal) music. It also of this short movement, neighbors Ds6. This neighboring suggests that we learn to trust our analytical instincts and perceptions motion is the first new gesture that we hear following with atonal music as much as we do with tonal music and that we not repetitions of the iconic first two chords. Two bars later, we require every interpretive impulse to be grounded by strongly can hear an appoggiatura as the unprepared Gs enters and methodological constraints. resolves down to Fs. The Ds-E-Ds neighbor tone was also shown in a reductive analysis in Lerdahl (2001, 354), but I. INTRODUCTION AND EXAMPLES Lerdahl apparently disagrees with my appoggiatura designation, instead equating both Gs and Fs as members of On the face of it, this paper makes a very simple and “departure” sonorities. -

CCSSA 25807 Booklet 14-08-2007 15:23 Pagina 1

CCSSA 25807_booklet 14-08-2007 15:23 Pagina 1 CHANNEL CLASSICS CCS SA 25807 Pieter Wispelwey violoncello Budapest Festival Orchestra Iván Fischer conductor Dvořák Concerto for Cello and Orchestra in b minor Op.104 Symphonic Variations for orchestra Op.78 CCSSA 25807_booklet 14-08-2007 15:23 Pagina 2 “Deeply communicative and highly individual performances.” New York Times “An outstanding cellist and a really wonderful musician” Gramophone “An agile technique and complete engagement with the music” New York Times CCSSA 25807_booklet 14-08-2007 15:23 Pagina 3 Pieter Wispelwey is among the first of a generation of performers who are equally at ease on the modern or the period cello. His acute stylistic awareness, combined with a truly original inter- pretation and a phenomenal technical mastery, has won the hearts of critics and public alike in repertoire ranging from JS Bach to Elliott Carter. Born in Haarlem, Netherlands, Wispelwey’s sophisticated musical personality is rooted in the training he received: from early years with Dicky Boeke and Anner Bylsma in Amsterdam to Paul Katz in the USA and William Pleeth in Great Britain. In 1992 he became the first cellist ever to receive the Netherlands Music Prize, which is awarded to the most promising young musician in the Netherlands. Highlights among future concerto performances include return engagements with the Rotterdam Philharmonic, London Philharmonic, Budapest Festival Orchestra, Dublin National Symphony, Copenhagen Philharmonic, Sinfonietta Cracovia, debuts with the Mahler Chamber Orchestra, Sydney, Melbourne and Adelaide Symphony, Dallas Symphony, Bordeaux National Orchestra, Strasbourg Philharmonic, Tokyo Symphony and Sapporo Symphony, as well as extensive touring in the Netherlands with the BBC Scotish Symphony and across Europe with the Basel Kammer- orchester to mark Haydn’s anniversary in 2009. -

GOLDBERG VARIATIONS - English Suite No

BHP 901 - BACH: GOLDBERG VARIATIONS - English Suite No. 5 in e - Millicent Silver, Harpsichord _____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ This disc, the first in our Heritage Performances Series, celebrates the career and the artistry of Millicent Silver, who for some forty years was well-known as a regular performer in London and on BBC Radio both as soloist and as harpsichordist with the London Harpsichord Ensemble which she founded with her husband John Francis. Though she made very few recordings, we are delighted to preserve this recording of the Goldberg Variations for its musical integrity, its warmth, and particularly the use of tonal dynamics (adding or subtracting of 4’ and 16’ stops to the basic 8’) which enhances the dramatic architecture. Millicent Irene Silver was born in South London on 17 November 1905. Her father, Alfred Silver, had been a boy chorister at St. George’s Chapel, Windsor where his singing attracted the attention of Queen Victoria, who had him give special performances for her. He earned his living playing the violin and oboe. His wife Amelia was an accomplished and busy piano teacher. Millicent was the second of their four children, and her musical talent became evident in time-honoured fashion when she was discovered at the age of three picking out on the family’s piano the tunes she had heard her elder brother practising. Eventually Millicent Silver won a scholarship to the Royal College of Music in London where, as was more common in those days, she studied equally both piano and violin. She was awarded the Chappell Silver Medal for piano playing and, in 1928, the College’s Tagore Gold Medal for the best student of her year. -

Evaluating Prolongation in Extended Tonality

Evaluating Prolongation in Extended Tonality <http://mod7.shorturl.com/prolongation.htm> Robert T. Kelley Florida State University In this paper I shall offer strategies for deciding what is structural in extended-tonal music and provide new theoretical qualifications that allow for a conservative evaluation of prolongational analyses. Straus (1987) provides several criteria for finding post-tonal prolongation, but these can simply be reduced down to one important consideration: Non-tertian music clouds the distinction between harmonic and melodic intervals. Because linear analysis depends upon this distinction, any expansion of the prolongational approach for non-tertian music must find alternative means for defining the ways in which transient tones elaborate upon structural chord tones to foster a sense of prolongation. The theoretical work that Straus criticizes (Salzer 1952, Travis 1959, 1966, 1970, Morgan 1976, et al.) fails to provide a method for discriminating structural tones from transient tones. More recently, Santa (1999) has provided associational models for hierarchical analysis of some post-tonal music. Further, Santa has devised systems for determining salience as a basis for the assertion of structural chords and melodic pitches in a hierarchical analysis. While a true prolongational perspective cannot be extended to address most post-tonal music, it may be possible to salvage a prolongational approach in a restricted body of post-tonal music that retains some features of tonality, such as harmonic function, parsimonious voice leading, or an underlying diatonic collection. Taking into consideration Straus’s theoretical proviso, we can build a model for prolongational analysis of non-tertian music by establishing how non-tertian chords may attain the status of structural harmonies.