Sukoon-Mag-V-3-Issue-1-2015

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Zena El Khalil Zena El Khalil, Born Year of the Dragon, Is a Visual Artist, Writer and Cultural Activist Based in Beirut, Lebanon

Zena el Khalil Zena el Khalil, born year of the Dragon, is a visual artist, writer and cultural activist based in Beirut, Lebanon. She has lived in Lagos, London and New York. Her work includes mixed media paintings, installations and performance and is a by-product of political and economic turmoil; focusing on issues of violence, gender and their place in our bubblegum culture. She has exhibited in the United States, Europe, Africa, Japan and the Middle East. While living in NYC, Zena co-founded xanadu*, an art collective dedicated to promoting emerging Arab and under - represented artists as a direct response to the 9-11 attacks which she witnessed. Currently, xanadu* is based in Beirut where Zena is focused on curating cultural events and publishing poets and comic book artists. During the 2006 invasion of Lebanon, Zena was one of the first largely followed Middle Eastern bloggers; her writings published in the international press, including the BBC, CNN, and Der Spiegel. The entire Guardian G2 supplement in July was dedicated to her blog, Beirut Update. In 2008, she was invited to speak at the Nobel Peace Center in Oslo and soon after, completed her memoir, Beirut, I Love You, now translated in several languages. Her publishers include The New York Review of Books and Saqi Books and Publishers Weekly gave her book a starred review. In an attempt to spread peace, Zena is often seen running around Beirut in a big pink wedding dress. In 2012, Zena was made a TED Fellow and has since given a few TED and TEDx talks. -

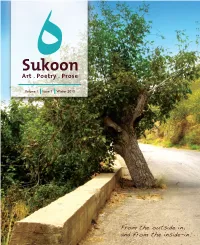

Sukoon Magazine Volume 1, Issue 1 Winter 2013

From the outside in, and from the inside-in. Sukoon is: an Arab-themed, English language, online literary magazine; the first of its kind in the Arab region, where es- tablished and emerging artists, po- Contents ets and writers of short stories and Volume 1, Issue 1, Winter 2013 personal essays, publish their origi- INTRODUCTION & INTERVIEWS nal work in English. Writers need not 1 Rewa Zeinati Editor’s Note be Arab, nor of Arab origin, but all 13 Rewa Zeinati An interview with writing and art must reflect the di- Naomi Shihab Nye versity and richness of the cultures POEMS of the Arab world. 3 Frank Dullaghan Losing the Language 4 Frank Dullaghan In a Place of Sukoon is an Arabic word mean- Darkness 5 Helen Wing Attrition ing “stillness.” By stillness we don’t 6 Helen Wing She Looks at mean silence, but rather the oppo- her Love 8 Helen Wing Misrata Dawn site of silence. What we mean by 18 Steven Schreiner Jesus Slept Here Sukoon is the stillness discovered 19 Zeina Hashem Beck The Language of Salaam within, when the artist continues to 20 Farah Chamma I am no follow the inner calling to express Palestinian 21 Kenneth E. Harrison, Jr Witness and create. 22 Hind Shoufani Manifesto 23 Louay Khraish Vola 24 Hajer Abdulsalam Birthday Wishes A calling that compels the artist to 26 Steven Schreiner Death May Take continue on the creative path for 26 Becky Kilsby Henna Days the sole reason that he/she does 27 Becky Kilsby #Trending 28 Zeina Hashem Beck A Few Love Lines to not know how not to. -

Re-Imagining Peace: Analyzing Syria’S Four Towns Agreement Through Elicitive Conflict Mapping

MASTERS OF PEACE 19 Lama Ismail Re-Imagining Peace: Analyzing Syria’s Four Towns Agreement through Elicitive Conflict Mapping innsbruck university press MASTERS OF PEACE 19 innsbruck university press Lama Ismail Re-Imagining Peace: Analyzing Syria’s Four Towns Agreement through Elicitive Conflict Mapping Lama Ismail Unit for Peace and Conflict Studies, Universität Innsbruck Current volume editor: Josefina Echavarría Alvarez, Ph.D This publication has been made possible thanks to the financial support of the Tyrolean Education Institute Grillhof and the Vice-Rectorate for Research at the University of Innsbruck. © innsbruck university press, 2020 Universität Innsbruck 1st edition www.uibk.ac.at/iup ISBN 978-3-903187-88-7 For Noura Foreword by Noura Ghazi1 I am writing this foreword on behalf of Lama and her book, in my capacity as a human rights lawyer of more than 16 years, specializing in cases of enforced disappearance and arbitrary detention. And also, as an activist in the Syrian uprisings. In my opinion, the uprisings in Syria started after decades of attempts – since the time of Asaad the father, leading up to the current conflict. Uprisings have taken up different forms, starting from the national democratic movement of 1979, to what is referred to as the Kurdish uprising of 2004, the ‘Damascus Spring,’ and the Damascus- Beirut declaration. These culminated in the civil uprisings which began in March 2011. The uprisings that began with the townspeople of Daraa paralleled the uprisings of the Arab Spring. Initially, those in Syria demanded for the release of political prisoners and for the uplift of the state of emergency, with the hope that this would transition Syria’s security state towards a state of law. -

AFAC Annual Report 2018

ANNUAL REPORT 2018 AFAC Annual Report 2018 2 3 ANNUAL REPORT 2018 ANNUAL REPORT 2018 4 5 About AFAC Strategic Areas of Work The Arab Fund for Arts and Culture - AFAC was founded in 2007 through Supporting the production of cultural and artistic work lies at the core of the initiative of Arab cultural activists as an independent foundation AFAC’s work. Since our inception, numerous changes have taken place to support individual artists, writers, researchers, intellectuals, as well in our funding programs in response to the needs, gaps, and emergence as organizations from the Arab region working in the field of arts and of new forms of expression and storytelling. The fund for supporting culture. Since its launch, AFAC’s programs have steadily expanded to novelists has transformed into encouraging other genres of creative cover cinema, documentary film, documentary photography, visual and writing, while the support for documentary filmmaking has expanded, performing arts, music, creative and critical writings, research on the adding a dedicated program for enhancing documentary photography. arts, entrepreneurship, trainings and regional events. Based in Beirut, The support that AFAC offers is not restricted to cultural and artistic AFAC works with artists and organizations all over the Arab region and work; it extends to cover research on the arts, to secure appropriate the rest of the world. channels of distribution and to guarantee the sustainability of pioneering cultural organizations in the Arab world, whether by way of financial Our -

Re-Imagining Peace

Master Thesis in the frame of the MA Program in Peace, Development, Security and International Conflict Transformation at the University of Innsbruck Re-Imagining Peace Analyzing Syria’s “Four Towns Agreement” through Elicitive Conflict Mapping In order to obtain the degree Master of Arts Submitted by Lama Ismail Supervised by Josefina Echavarría Álvarez Innsbruck, 2019 Re-Imagining Peace Acknowledgments I dedicate this section to the many people that made the writing of this thesis bearable, and more importantly, possible. First, I thank my thesis adviser Dr. Josefina Echavarría Álvarez for accompanying me while writing the thesis, and for allowing me the space to grow through writing. When I took your Elicitive Conflict Mapping class, I struggled with some of the concepts at first. At some point during a private conversation, you told me: “every person in a conflict has a body.” That changed everything, and it was at that moment I decided I want to use Elicitive Conflict Mapping for my thesis. Thank you Josefina for everything you have done for me and for this thesis. I am so grateful for having worked on this project with you. I also thank all the faculty at the University of Innsbruck, especially Wolfgang, Norbert and Daniela for their continuous support since the first day we met. I also thank my parents for having so much faith in me and for listening to my ideas and challenging them. I thank my sisters, Sarah and Aya, for being my lighthouse. And to my sister Aya for spending hours on editing the form of the thesis. -

Palestinian Filmmakers … and Their (Latest) Works

PALESTINIAN FILMMAKERS … AND THEIR (LATEST) WORKS Hiam Abbass is an acclaimed Palestinian actress and film director who was born in Nazareth and grew up in a Palestinian village in the northern Galilee. Abbass has been featured in local as well as international films such as Haifa, The Gate of the Sun, Paradise Now, Munich, The Syrian Bride, Amreeka, The Visitor, Miral and Dégradé. She was nominated for Best Actress at the Israeli Film Academy Award for her performance in Eran Rikilis’ Lemon Tree. She has also written and directed the short films Le Pain, La Danse Eternelle, and Le Donne Della Vucciria. She has just completed the shooting of two new features, Rock the Casbah, and May in the Summer. Inheritance is her directorial debut. Inheritance 2012. Drama. 88 min A Palestinian family living in the north of the Galilee gathers to celebrate the wedding of one of their daughters, as war rages between Israel and Lebanon. The many family members symbolize a community struggling to maintain their identity, torn between modernity and tradition. When the youngest daughter, Hajar, returns on this occasion, she tells her father and patriarch Abu Majd, who has always encouraged her to learn and to discover the world, about the man she loves, an English art teacher. When the father falls into a coma and inches toward death, internal conflicts explode and the familial battles become as merciless as the outside war. Mohammed Abu Nasser (known as ‘Arab’) and his twin brother and partner in filmmaking Ahmed Abu Nasser (known as ‘Tarzan’) were born in Gaza in 1988. -

Annual Report 2011

ANNUAL REPORT 2011 CONTENTS Fall Residency Group Photograph 4 Letter from the Director 5 The Fall Residency 6 Calendar of Events 7 Participants List & Writers’ Activities 12 The Life of Discovery 18 Writers in Motion 22 Between the Lines 26 Overseas Reading Tours 28 Distance Learning 32 Virtual Writing University 38 Publications 39 Website Redesign 40 Program Support 41 Contributing Organizations 47 “The Last Piano” 48 4 GREETINGS FROM IOWA CITY A letter from Director Christopher Merrill time, it’s clear that the Engles’ vision for the IWP ton D.C., New York City (among other cities); and was not just a revolutionary idea but a necessary who produced new creative work—an one. In a world in which we—all seven billion of impressive1,600 pages of prose, poems, essays, us—grow ever more connected through technol- articles, and plays. ogy and travel, our founders’ wish that the IWP Meantime, we designed a beautiful new would exist as a space for cross-cultural exchange, website, which makes our deep cache of archived dialogue, and camaraderie is more essential than content available to the world. From original ever. book publications and the program’s literary Our 2011 annual report is a window journal, 91st Meridian, to our archive of photos, through which we hope you’ll see that the Engles’ interviews, and author biographies, the new site founding sense of purpose and generosity is very gives visitors access to the writing and writers much still alive, even as the IWP engages in a that have dened the program for nearly half a Photo: Ram Devineni bolder and more diverse range of programming century. -

Zena El-Khalil

BIOGRAPHY – ZENA EL KHALIL Zena el Khalil believes in the positive impact that art can have on the world. Born year of the Dragon, Zena is an artist, author, cultural activist and yoga instructor based in Beirut, Lebanon. She holds a Masters of Fine Arts from the School of Visual Arts in NYC, a Bachelor of Graphic Design from the American University of Beirut and a 200 RYT teaching certificate from the Yoga Alliance. El Khalil exhibits internationally, including New York, San Francisco, Miami, London, Paris, Tokyo, and Dubai. She has also held solo exhibitions in Lagos, London, Munich, Turin and Beirut and regularly participates in international art fairs. Zena uses visual art, site-specific installation, performance and ritual to explore and heal the war-torn history of Lebanon and other global sites of trauma. Believing in the importance of community engagement with contemporary art, she also curates cultural events that create platforms for dialogue and exchange. Though her collective, the Ātman Institute, Zena curates events, workshops and concerts dedicated to healing and reconciliation, through the mediums of ceremony, sound and art. Merging art and healing modalities, Zena has been conducting healing ceremonies across Lebanon in spaces that have historically endured trauma and violence, such as environmental disasters, massacres and even the torturing of human beings. With the intention of transforming these places and objects in them into generators peace and reconciliation in nature and with communities, these ceremonies include a process of meditation, chanting, dancing, whirling and a purifying fire ritual through which she create paintings, sculptures, sound and video art. -

LAU University Medical Center-Rizk Hospital: Health for Lebanon

LAU University Medical Center-Rizk Hospital: Health for Lebanon LAU’s new University Medical Center-Rizk Hospital represents the establishment of a state-of-the-art multidisciplinary learning, training and healing center. The university’s exclusive partnership with UMC-RH provides students from LAU’s distinguished medical and health industry schools unprecedented access to a diverse, high-tech facility, with the goal of building a new generation of skilled and deeply compassionate practitioners. UMC-RH’s patient-centered focus ensures excellent treatment tailored to patients’ individual needs in accordance with the university’s principles and values of safe, holistic medical care. The medical center is also the site for LAU’s Standardized Patient Instructor program—the only one of its kind in Lebanon that trains volunteers to simulate real patients to be interviewed and examined by students, creating a realistic doctor- patient hospital experience. Only at LAU & ALUMNI BULLETIN VOLUME 11 | issue nº 4 FEATURES CONTENTS 4 Still Held Back: 28 Teach for Lebanon Brings Quality Lebanese Women in Education to Rural Poor Power and Politics 29 LAU-MEPI Program to Empower Women An electoral loss for the women of Lebanon Kicks Off 30 LAU and the Université de Montréal Promote Democracy and Citizen 8 The Politics of Conflict and Empowerment Despair: Middle Eastern 31 Expanding Education: LAU’s New Medical Art Rises in the West School Welcomes Inaugural Class The value of politics in art 32 12th Annual International University Theater Festival 14 New Media=New Politics? 34 The New Face of LAU Citizen journalism and the drive 36 LAU Profile in Politics: Nimat Kanaan (’58) to represent 37 Faculty & Staff on the Move 17 From Washington to Beirut 38 Student Achievement Marc Abizeid served as a top aide to U.S. -

Palestinian Filmmakers and Their (Latest) Works

PALESTINIAN FILMMAKERS AND THEIR (LATEST) WORKS DIRECTOR FILM – DRAMA | COMEDY 1. Hiam Abbass is an acclaimed Palestinian actress Inheritance. 2012. Drama. 88 min and film director who was born in Nazareth and As war rages between Israel and Lebanon, a Pales- grew up in a Palestinian village in the northern tinian family living in the north of Galilee gathers Galilee. Abbass has been featured in local as to celebrate the wedding of one of their daugh- well as international films such as Haïfa, The ters. The many family members symbolize a com- Gate Of The Sun, Paradise Now, Munich, The munity struggling to maintain their identity, torn Syrian Bride, Amreeka, The Visitor, Miral and between modernity and tradition. When the Dégradé. She was nominated for Best Actress at youngest daughter, Hajar, returns on this occasion, the Israeli Film Academy Award for her per- she tells her father and patriarch Abu Majd, who formance in Eran Rikilis’ Lemon Tree. She has also written and has always encouraged her to learn and to discover directed the short films Le Pain, La Danse Eternelle, and Le Donne the world, about the man she loves, an English art Della Vucciria. She has just completed the shooting of two new teacher. When the father falls into a coma and features, Rock the Casbah, and May in the Summer. Inheritance is her inches toward death, internal conflicts explode and directorial debut. the familial battles become as merciless as the out- side war. 2. Mohammed Abu Nasser (known as Dégradé. 2015. Comedy Drama. 1h 25min ‘Arab’) and his twin brother and Filmed in Jordan and inspired by true events from partner in filmmaking Ahmed Abu Gaza in 2007, the film depicts Christine’s Salon as a Nasser (known as ‘Tarzan’) were sanctuary from the outside world and the banal born in Gaza in 1988. -

AFAC 2014 Annual Report

AFAC 2014 Annual Report AFAC is an independent Arab initiative generously supported by a number of foundations, corporations and individuals in and outside the Arab region. Yemeni Women with Fighting Spirits Women Yemeni Cover photo: Amira Al-Sharif, Cover photo: Amira Al-Sharif, Media partners 2 Individual Donors Abla Lahoud • Akram Zaatari • Ali Hassan Al Husseini • Amin el Maghraby • Amr Ben Halim • Anne-Dominique Janecek • Anthony and Sandra Tamer • Anthony Baladi • Carole N. Marshi • Chatila Fustok • Dania Nassief • Danya Alhamrani • Dina and Amine Jabali • Dina and Mohamad Zameli • Donald Zilkha • Fahd al-Rajaan • Fayez Takieddine • Fouad Al-Khadra • Gail and Malek Antabi • Gidon Kremer • Gregory Evans • Habib and Lara Kairouz • Hala Abukhadra • Hamza al-Kholi • Hanan Sayed and Steve Worell • Hani Kalouti • HRH Princess Adila bint Abdullah bin Abdulaziz Al Saud • Huda Kitmitto • Imane Farès • Issaac R Souede • Jamil El-Khazen • Jawdat Shawwa • Joslyn Barnes • Kathryn Sutherland • Khalil, Maria and Aeran Amiouni • Luma and Zade Zalatimo • Mariam Farag and Augusto Costa • Marwan Al-Sayeh • Mary Evangelista • Maya Abdulmajeed and Tarek Sakka • Maya al-Khalil • Nabil Qaddumi • Nada Saab • Nafez Jundi • Najat Rizk • Nayla Saba Karkour • Olfat Al-Mutlaq Juffali • Omar Karkour • Omar Kodmani • Omar Qattan • Patrick Knowles • Pierre Olivier Sarkozy • Paula Mueller and Philippe Salomon • Rana Sadik • Rania and Omar Ashur • Rashad Khourshid • Riad and Rafa Mourtada • Roberto Boghossian • Rula Alami • Salah Fustok • Sara Salem Mohammad Binladen • Sawsan and Ayman Asfari • Sawsan Jafar • Sherine Jafar • Suad al-Housseini • Suheil Sabbagh • Tafeeda and Ali Jarbawi • Talal and Nada Idriss • Taymour Grahne • Tayseer Barakat • Wafa Saab • Waleed Al Banawi • Waleed Ghafari • Walid Ramadan • William J. -

Interchange Programme Icbook of Projects 2010

Icbook of projects 2010 Interchange Programme with the support of Filmmaking can be a place where stories still explore Seven years ago the Dubai International Film the infinity of possible worlds and experiences. This Festival was launched with the mission to celebrate exploration takes time and faith that it will not be in excellence in cinema, using it as a medium vain. Phases of solitude, and maybe even loneliness, to promote open dialogue between cultures can alternate with phases of intense collaboration. and nations; to nurture and develop local and We tell ourselves our stories, we share them and international talent; and to accelerate and foster the see them become through this process. Being able growth of the industry. to nurture ideas, in the working together with other filmmakers, story editors, creative producers can The Interchange programme speaks directly to this help to bear the weight of the whole process, and intention. bring it to a gratifying conclusion. In creating Interchange the Festival has developed TorinoFilmLab was born in April 2008 with a relationships with two leading training providers in precise aim: linking training, development and Europe - TorinoFilmLab and EAVE - and with support TorinoFilmLab funding activities. We want to support filmmakers from the MEDIA Mundus has opened up new from all over the world at their first or second opportunities for filmmakers from the Gulf region Interchange feature, following them, as far as possible, from the and selected countries in the Middle East to benefit beginning to the end of their path. This process from this rich source of experience.