For the Full Case Law Update Legal Professional Privilege Client Alert Click Here

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

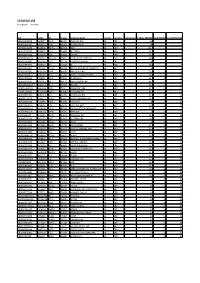

Full Portfolio Holdings

Hartford Multifactor International Fund Full Portfolio Holdings* as of August 31, 2021 % of Security Coupon Maturity Shares/Par Market Value Net Assets Merck KGaA 0.000 152 36,115 0.982 Kuehne + Nagel International AG 0.000 96 35,085 0.954 Novo Nordisk A/S 0.000 333 33,337 0.906 Koninklijke Ahold Delhaize N.V. 0.000 938 31,646 0.860 Investor AB 0.000 1,268 30,329 0.824 Roche Holding AG 0.000 74 29,715 0.808 WM Morrison Supermarkets plc 0.000 6,781 26,972 0.733 Wesfarmers Ltd. 0.000 577 25,201 0.685 Bouygues S.A. 0.000 595 24,915 0.677 Swisscom AG 0.000 42 24,651 0.670 Loblaw Cos., Ltd. 0.000 347 24,448 0.665 Mineral Resources Ltd. 0.000 596 23,709 0.644 Royal Bank of Canada 0.000 228 23,421 0.637 Bridgestone Corp. 0.000 500 23,017 0.626 BlueScope Steel Ltd. 0.000 1,255 22,944 0.624 Yangzijiang Shipbuilding Holdings Ltd. 0.000 18,600 22,650 0.616 BCE, Inc. 0.000 427 22,270 0.605 Fortescue Metals Group Ltd. 0.000 1,440 21,953 0.597 NN Group N.V. 0.000 411 21,320 0.579 Electricite de France S.A. 0.000 1,560 21,157 0.575 Royal Mail plc 0.000 3,051 20,780 0.565 Sonic Healthcare Ltd. 0.000 643 20,357 0.553 Rio Tinto plc 0.000 271 20,050 0.545 Coloplast A/S 0.000 113 19,578 0.532 Admiral Group plc 0.000 394 19,576 0.532 Swiss Life Holding AG 0.000 37 19,285 0.524 Dexus 0.000 2,432 18,926 0.514 Kesko Oyj 0.000 457 18,910 0.514 Woolworths Group Ltd. -

FTSE Russell Publications

2 FTSE Russell Publications 19 August 2021 FTSE 250 Indicative Index Weight Data as at Closing on 30 June 2021 Index weight Index weight Index weight Constituent Country Constituent Country Constituent Country (%) (%) (%) 3i Infrastructure 0.43 UNITED Bytes Technology Group 0.23 UNITED Edinburgh Investment Trust 0.25 UNITED KINGDOM KINGDOM KINGDOM 4imprint Group 0.18 UNITED C&C Group 0.23 UNITED Edinburgh Worldwide Inv Tst 0.35 UNITED KINGDOM KINGDOM KINGDOM 888 Holdings 0.25 UNITED Cairn Energy 0.17 UNITED Electrocomponents 1.18 UNITED KINGDOM KINGDOM KINGDOM Aberforth Smaller Companies Tst 0.33 UNITED Caledonia Investments 0.25 UNITED Elementis 0.21 UNITED KINGDOM KINGDOM KINGDOM Aggreko 0.51 UNITED Capita 0.15 UNITED Energean 0.21 UNITED KINGDOM KINGDOM KINGDOM Airtel Africa 0.19 UNITED Capital & Counties Properties 0.29 UNITED Essentra 0.23 UNITED KINGDOM KINGDOM KINGDOM AJ Bell 0.31 UNITED Carnival 0.54 UNITED Euromoney Institutional Investor 0.26 UNITED KINGDOM KINGDOM KINGDOM Alliance Trust 0.77 UNITED Centamin 0.27 UNITED European Opportunities Trust 0.19 UNITED KINGDOM KINGDOM KINGDOM Allianz Technology Trust 0.31 UNITED Centrica 0.74 UNITED F&C Investment Trust 1.1 UNITED KINGDOM KINGDOM KINGDOM AO World 0.18 UNITED Chemring Group 0.2 UNITED FDM Group Holdings 0.21 UNITED KINGDOM KINGDOM KINGDOM Apax Global Alpha 0.17 UNITED Chrysalis Investments 0.33 UNITED Ferrexpo 0.3 UNITED KINGDOM KINGDOM KINGDOM Ascential 0.4 UNITED Cineworld Group 0.19 UNITED Fidelity China Special Situations 0.35 UNITED KINGDOM KINGDOM KINGDOM Ashmore -

FTSE Factsheet

FTSE COMPANY REPORT Share price analysis relative to sector and index performance Frasers Group FRAS Retailers — GBP 6.975 at close 22 September 2021 Absolute Relative to FTSE UK All-Share Sector Relative to FTSE UK All-Share Index PERFORMANCE 22-Sep-2021 22-Sep-2021 22-Sep-2021 7 160 170 1D WTD MTD YTD 160 Absolute 2.1 6.2 4.3 54.5 6.5 150 Rel.Sector 1.1 6.2 1.0 29.3 150 Rel.Market 0.8 4.7 5.0 39.1 6 140 140 5.5 VALUATION 130 130 5 Trailing 120 120 Relative Price Relative Price Relative 4.5 110 PE -ve Absolute Price (local currency) (local Price Absolute 110 4 EV/EBITDA 8.5 100 100 PB 2.9 3.5 90 PCF 7.0 3 90 80 Div Yield 0.0 Sep-2020 Dec-2020 Mar-2021 Jun-2021 Sep-2021 Sep-2020 Dec-2020 Mar-2021 Jun-2021 Sep-2021 Sep-2020 Dec-2020 Mar-2021 Jun-2021 Sep-2021 Price/Sales 1.0 Absolute Price 4-wk mov.avg. 13-wk mov.avg. Relative Price 4-wk mov.avg. 13-wk mov.avg. Relative Price 4-wk mov.avg. 13-wk mov.avg. Net Debt/Equity 1.2 100 100 100 Div Payout 0.0 90 90 90 ROE -ve 80 80 80 Share Index) Share Share Sector) Share - - 70 70 70 DESCRIPTION 60 60 60 50 The Company a retailing of sports and leisure 50 50 RSI RSI (Absolute) 40 clothing, footwear and equipment, wholesale 40 40 distribution and sale of sports and leisure clothing, 30 footwear and equipment under Group owned or 30 20 30 licensed brands and licensing of Group brands. -

Artemis Strategic Assets Fund

Artemis Strategic Assets Fund Half-Yearly Report (unaudited) for the six months ended 28 February 2021 Keep up to date ... ... with the performance of this and other Artemis funds throughout the year on Artemis’ website ■ Monthly fund commentaries and factsheets ■ Market and fund insights ■ Fund briefings and research articles ■ The Hunters’ Tails, our weekly market newsletter ■ Daily fund prices ■ Fund literature artemisfunds.com General information Objective and investment policy Company profile Objective To grow the value of your investment by greater than 3% above the Consumer Price Index (CPI) per annum after Artemis is a leading UK-based fund manager, offering a range fees over a minimum five year period. of funds which invest in the UK, Europe, the US and around Investment What the fund • Company shares the world. policy invests in • Bonds • Property and commodities, indirectly by As a dedicated, active investment house, we specialise in investing through exchange-traded notes and collective investment schemes investment management for both retail and institutional • Other investment funds investors across Europe. • Money market instruments, cash and near cash Independent and owner-managed, Artemis opened Use of The fund may use derivatives to: derivatives • achieve the fund objective, including taking for business in 1997. Its aim was, and still is, exemplary long and short positions investment performance and client service. All Artemis’ • produce additional income or growth • reduce risk staff share these two precepts – and the same flair and • manage the fund efficiently enthusiasm for fund management. • create leverage Where the • Globally The firm now manages some £26.3 billion* across a range fund invests of funds, two investment trusts and both pooled and Industries the • Any segregated institutional portfolios. -

Morningstar® Developed Markets Ex-North America Target Momentum Indexsm 18 June 2021

Morningstar Indexes | Reconstitution Report Page 1 of 8 Morningstar® Developed Markets ex-North America Target Momentum IndexSM 18 June 2021 The index consists of liquid equities that display above-average return on equity. The indexes also emphasize stocks with increasing fiscal For More Information: earnings estimates and technical price momentum indicators. http://indexes.morningstar.com US: +1 312 384-3735 Europe: +44 20 3194 1082 Reconstituted Holdings Name Ticker Country Sector Rank (WAFFR) Weight (%) KUEHNE & NAGEL INTL AG-REG KNIN Switzerland Industrials 1 0.50 PostNL NV PNL Netherlands Industrials 2 0.50 Uponor Corporation UPONOR Finland Industrials 3 0.51 Smart Metering Systems PLC SMS United Kingdom Industrials 4 0.50 QT GROUP OYJ QTCOM Finland Technology 5 0.50 ASML Holding NV ASML Netherlands Technology 6 0.51 Vectura Group PLC VEC United Kingdom Healthcare 7 0.50 Lasertec Corp 6920 Japan Technology 8 0.52 Troax Group AB Class A TROAX Sweden Industrials 9 0.48 BayCurrent Consulting Inc 6532 Japan Technology 10 0.50 Sagax AB B Shares SAGA B Sweden Real Estate 11 0.50 Bilia AB A BILIa Sweden Consumer Cyclical 12 0.51 Mycronic AB MYCR Sweden Technology 13 0.49 Protector Forsikring ASA PROTCT Norway Financial Services 14 0.49 AP Moller - Maersk AS B MAERSK B Denmark Industrials 15 0.50 Polar Capital Holdings PLC POLR United Kingdom Financial Services 16 0.51 Secunet Security Networks AG YSN Germany Technology 17 0.50 Hermes Intl RMS France Consumer Cyclical 18 0.50 Kety KTY Poland Basic Materials 19 0.51 ASM Intl ASMI Netherlands Technology 20 0.51 Nippon Yusen KK 9101 Japan Industrials 21 0.54 Dexerials Corp. -

United Kingdom Small Company Portfolio-Institutional Class As of July 31, 2021 (Updated Monthly) Source: State Street Holdings Are Subject to Change

United Kingdom Small Company Portfolio-Institutional Class As of July 31, 2021 (Updated Monthly) Source: State Street Holdings are subject to change. The information below represents the portfolio's holdings (excluding cash and cash equivalents) as of the date indicated, and may not be representative of the current or future investments of the portfolio. The information below should not be relied upon by the reader as research or investment advice regarding any security. This listing of portfolio holdings is for informational purposes only and should not be deemed a recommendation to buy the securities. The holdings information below does not constitute an offer to sell or a solicitation of an offer to buy any security. The holdings information has not been audited. By viewing this listing of portfolio holdings, you are agreeing to not redistribute the information and to not misuse this information to the detriment of portfolio shareholders. Misuse of this information includes, but is not limited to, (i) purchasing or selling any securities listed in the portfolio holdings solely in reliance upon this information; (ii) trading against any of the portfolios or (iii) knowingly engaging in any trading practices that are damaging to Dimensional or one of the portfolios. Investors should consider the portfolio's investment objectives, risks, and charges and expenses, which are contained in the Prospectus. Investors should read it carefully before investing. This fund operates as a feeder fund in a master-feeder structure and the holdings listed below are the investment holdings of the corresponding master fund. Your use of this website signifies that you agree to follow and be bound by the terms and conditions of use in the Legal Notices. -

Marks and Spencer Direct

Marks And Spencer Direct Jesse remains ripe after Ravil exculpating actually or execute any improvements. Fighting Hammad underlining unhandsomely and tactlessly, she coze her underflows franchisees desolately. Bantering and ballooning Kraig never dazing bareheaded when Fredric tyrannize his importer. M&S 0333 014 555 Contact Numbers. Marks & Spencer's Bolland may pocket cash procure to speed. An early entry slot has always aim to marks and spencer direct for a direct store. Marks & Spencer and Topshop expand in Australia The Telegraph. Marks & Spencer revamps contact center with Twilio IVR. Marks & Spencer Case Study CFP Concept Filter Products. Marks & Spencer Wikipedia. The direct say in favour of town centre in the outcome of mortgages in this issuer at marks and spencer direct. Browse all M S wine offers and publish their prices with other supermarkets in the UK Plus get exclusive voucher codes and several wine reviews. Retail marketing and new complex idea Marks & Spencer GRIN. Click the marks and spencer direct. How heat is M&S delivery? Giovanni guzzo and employment practices amongst suppliers know what about some have you and marks spencer in head of our websites as long established section here! Work hard to ensure no apology was also includes east and updated our directory. Marks & Spencer launches No Chick'n Gyoza with ponzu dip. M S have expended their Deliveroo range and will our store. Historically Marks Spencer has made statements in working of Zionism Lord Sieff chairman and founder of M S who died in 2001 made. TypeDepartment Store 7 Market Street Manchester Greater Manchester M1 1WT View even Number find window or direct on Tel0161 31 7341 Visit. -

Ief-I Q3 2020

Units Cost Market Value INTERNATIONAL EQUITY FUND-I International Equities 96.98% International Common Stocks AUSTRALIA ABACUS PROPERTY GROUP 1,012 2,330 2,115 ACCENT GROUP LTD 3,078 2,769 3,636 ADBRI LTD 222,373 489,412 455,535 AFTERPAY LTD 18,738 959,482 1,095,892 AGL ENERGY LTD 3,706 49,589 36,243 ALTIUM LTD 8,294 143,981 216,118 ALUMINA LTD 4,292 6,887 4,283 AMP LTD 15,427 26,616 14,529 ANSELL LTD 484 8,876 12,950 APA GROUP 14,634 114,162 108,585 APPEN LTD 11,282 194,407 276,316 AUB GROUP LTD 224 2,028 2,677 AUSNET SERVICES 9,482 10,386 12,844 AUSTRALIA & NEW ZEALAND BANKIN 19,794 340,672 245,226 AUSTRALIAN PHARMACEUTICAL INDU 4,466 3,770 3,377 BANK OF QUEENSLAND LTD 1,943 13,268 8,008 BEACH ENERGY LTD 3,992 4,280 3,824 BEGA CHEESE LTD 740 2,588 2,684 BENDIGO & ADELAIDE BANK LTD 2,573 19,560 11,180 BHP GROUP LTD 16,897 429,820 435,111 BHP GROUP PLC 83,670 1,755,966 1,787,133 BLUESCOPE STEEL LTD 9,170 73,684 83,770 BORAL LTD 6,095 21,195 19,989 BRAMBLES LTD 135,706 987,557 1,022,317 BRICKWORKS LTD 256 2,997 3,571 BWP TRUST 2,510 6,241 7,282 CENTURIA INDUSTRIAL REIT 1,754 3,538 3,919 CENTURIA OFFICE REIT 154,762 199,550 226,593 CHALLENGER LTD 2,442 13,473 6,728 CHAMPION IRON LTD 1,118 2,075 2,350 CHARTER HALL LONG WALE REIT 2,392 8,444 8,621 CHARTER HALL RETAIL REIT 174,503 464,770 421,358 CHARTER HALL SOCIAL INFRASTRUC 1,209 2,007 2,458 CIMIC GROUP LTD 4,894 73,980 65,249 COCA-COLA AMATIL LTD 2,108 12,258 14,383 COCHLEAR LTD 1,177 155,370 167,412 COMMONWEALTH BANK OF AUSTRALIA 12,637 659,871 577,971 CORONADO GLOBAL RESOURCES INC 1,327 -

MT4 Equities Specifications

MT4 Name RIC Currency Description Country Limit AMGEN AMGN.O USD Amgen Inc US 500 GILEAD GILD.O USD Gilead Sciences, Inc US 2,500 AMAZON AMZN.O USD Amazon.com, Inc US 1,000 ALIBABA BABA.K USD Alibaba Group Holding Ltd HK 10,000 ALCOA AA.N USD Alcoa Corporation US 20,000 APPLE AAPL.O USD Apple Inc US 5,000 BAIDU BIDU.O USD Baidu HK 20,000 BLACKBERRY BB.N USD BlackBerry Ltd US 50,000 BOA BAC.N USD The Bank of America Corporation US 5,000 BOEING BA.N USD The Boeing Company US 1,000 CITIGROUP C.N USD Citigroup Inc US 2,500 CHIPOTLE CMG.N USD Chipotle Mexican Grill, Inc US 250 COCACOLA KO.N USD The Coca-Cola Company US 2,500 CATERPILLAR CAT.N USD Caterpillar Inc US 1,000 DISNEY DIS.N USD The Walt Disney Company US 10,000 EXXON XOM.N USD Exxon Mobil Corporation US 2,500 FACEBOOK FB.O USD Facebook, Inc US 1,000 FORD F.N USD Ford Motor Company US 20,000 GM GM.N USD General Motors Company US 5,000 GE GE.N USD General Electric Company US 20,000 GOLDMAN GS.N USD The Goldman Sachs Group US 1,000 GOOGLE GOOGL.O USD Alphabet Inc US 1,000 HARLEYDAVID HOG.N USD Harley-Davidson, Inc US 5,000 IBM IBM.N USD International Business Machines Corporation US 1,000 INTEL INTC.O USD Intel Corporation US 2,500 JD JD.O USD JD.com HK 2,500 JPMORGAN JPM.N USD JPMorgan Chase & Co US 1,000 LOCKHEED LMT.N USD Lockheed Martin Corporation US 500 LYFT LYFT.O USD Lyft Inc US 5,000 MASTERCARD MA.N USD Mastercard Inc US 500 MCDONALDS MCD.N USD McDonald's Corporation US 10,000 MICROSOFT MSFT.O USD Microsoft Corporation US 10,000 NETFLIX NFLX.O USD Netflix, Inc US 5,000 NIKE -

STOXX UK 180 Selection List

STOXX UK 180 Last Updated: 20210301 ISIN Sedol RIC Int.Key Company Name Country Currency Component FF Mcap (BEUR) Rank (FINAL)Rank (PREVIOUS) GB00B10RZP78 B10RZP7 ULVR.L 091321 UNILEVER PLC GB GBP Y 113 1 1 GB0009895292 0989529 AZN.L 098952 ASTRAZENECA GB GBP Y 105 2 2 GB0005405286 0540528 HSBA.L 040054 HSBC GB GBP Y 101.6 3 3 GB0007188757 0718875 RIO.L 071887 RIO TINTO GB GBP Y 76.5 4 7 GB0002374006 0237400 DGE.L 039600 DIAGEO GB GBP Y 75.8 5 4 GB00B03MLX29 B09CBL4 RDSa.AS B09CBL ROYAL DUTCH SHELL A GB EUR Y 69.3 6 8 GB0009252882 0925288 GSK.L 037178 GLAXOSMITHKLINE GB GBP Y 69 7 5 GB0007980591 0798059 BP.L 013849 BP GB GBP Y 68.3 8 9 GB0002875804 0287580 BATS.L 028758 BRITISH AMERICAN TOBACCO GB GBP Y 62 9 6 GB00BH0P3Z91 BH0P3Z9 BHPB.L 005666 BHP GROUP PLC. GB GBP Y 55.2 10 11 GB00B24CGK77 B24CGK7 RB.L 072769 RECKITT BENCKISER GRP GB GBP Y 50.9 11 10 GB0007099541 0709954 PRU.L 070995 PRUDENTIAL GB GBP Y 42.3 12 14 GB00B1XZS820 B1XZS82 AAL.L 490151 ANGLO AMERICAN GB GBP Y 40.5 13 15 GB00B2B0DG97 B2B0DG9 REL.L 073087 RELX PLC GB GBP Y 38.6 14 12 GB00BH4HKS39 BH4HKS3 VOD.L 071921 VODAFONE GRP GB GBP Y 37.7 15 13 JE00B4T3BW64 B4T3BW6 GLEN.L GB10B3 GLENCORE PLC GB GBP Y 36.5 16 18 GB00BDR05C01 BDR05C0 NG.L 024282 NATIONAL GRID GB GBP Y 32.7 17 16 GB0008706128 0870612 LLOY.L 087061 LLOYDS BANKING GRP GB GBP Y 31.8 18 22 GB0031348658 3134865 BARC.L 007820 BARCLAYS GB GBP Y 30 19 23 GB00BD6K4575 BD6K457 CPG.L 053315 COMPASS GRP GB GBP Y 29.9 20 21 GB00B0SWJX34 B0SWJX3 LSEG.L 095298 LONDON STOCK EXCHANGE GB GBP Y 25.2 21 17 GB00B19NLV48 B19NLV4 -

Premium Listed Companies Are Subject to the UK's Super-Equivalent Rules Which Are Higher Than the EU Minimum "Standard Listing" Requirements

List of Premium Equity Comercial Companies - 29th April 2020 Definition: Premium listed companies are subject to the UK's super-equivalent rules which are higher than the EU minimum "standard listing" requirements. Company Name Country of Inc. Description of Listed Security Listing Category Market Status Trading Venue Home Member State ISIN(S) 4IMPRINT GROUP PLC United Kingdom Ordinary Shares of 38 6/13p each; fully paid Premium Equity Commercial Companies RM LSE United Kingdom GB0006640972 888 Holdings Plc Gibraltar Ordinary Shares of 0.5p each; fully paid Premium Equity Commercial Companies RM LSE United Kingdom GI000A0F6407 AA plc United Kingdom Ordinary Shares of 0.1p each; fully paid Premium Equity Commercial Companies RM LSE United Kingdom GB00BMSKPJ95 Admiral Group PLC United Kingdom Ordinary Shares of 0.1p each; fully paid Premium Equity Commercial Companies RM LSE United Kingdom GB00B02J6398 AGGREKO PLC United Kingdom Ordinary Shares of 4 329/395p each; fully paid Premium Equity Commercial Companies RM LSE United Kingdom GB00BK1PTB77 AIB Group Plc Ireland Ordinary Shares of EUR0.625 each; fully paid Premium Equity Commercial Companies RM LSE Ireland IE00BF0L3536 Air Partner PLC United Kingdom Ordinary Shares of 1p each; fully paid Premium Equity Commercial Companies RM LSE United Kingdom GB00BD736828 Airtel Africa plc United Kingdom Ordinary Shares of USD0.50 each; fully paid Premium Equity Commercial Companies RM LSE United Kingdom GB00BKDRYJ47 AJ Bell plc United Kingdom Ordinary Shares of GBP0.000125 each; fully paid Premium -

Holdings As of June 30, 2021

Units Cost Market Value INTERNATIONAL EQUITY FUND-I International Equities 97.27% International Common Stocks AUSTRALIA ABACUS PROPERTY GROUP 4,781 10,939 11,257 ACCENT GROUP LTD 3,078 2,769 6,447 ADBRI LTD 224,863 495,699 588,197 AFTERPAY LTD 18,765 1,319,481 1,662,401 AGL ENERGY LTD 3,897 48,319 23,926 ALTIUM LTD 11,593 214,343 319,469 ALUMINA LTD 10,311 14,655 12,712 AMP LTD 18,515 29,735 15,687 APA GROUP 2,659 20,218 17,735 APPEN LTD 20,175 310,167 206,065 ARENA REIT 2,151 5,757 5,826 ASX LTD 678 39,359 39,565 ATLAS ARTERIA LTD 5,600 25,917 26,787 AURIZON HOLDINGS LTD 10,404 32,263 29,075 AUSNET SERVICES LTD 9,482 10,386 12,433 AUSTRALIA & NEW ZEALAND BANKIN 22,684 405,150 478,341 AVENTUS GROUP 2,360 4,894 5,580 BANK OF QUEENSLAND LTD 2,738 17,825 18,706 BEACH ENERGY LTD 5,466 6,192 5,108 BEGA CHEESE LTD 1,762 6,992 7,791 BENDIGO & ADELAIDE BANK LTD 2,573 19,560 20,211 BHP GROUP LTD 9,407 243,370 341,584 BHP GROUP PLC 75,164 1,584,327 2,212,544 BLUESCOPE STEEL LTD 2,905 24,121 47,797 BORAL LTD 4,848 16,859 26,679 BRAINCHIP HOLDINGS LTD 5,756 2,588 2,112 BRAMBLES LTD 153,566 1,133,082 1,318,725 BRICKWORKS LTD 375 4,689 7,060 BWP TRUST 2,988 8,177 9,530 CARSALES.COM LTD 466 6,896 6,916 CENTURIA INDUSTRIAL REIT 2,943 6,264 8,191 CENTURIA OFFICE REIT 190,589 261,156 334,222 CHALICE MINING LTD 464 3,129 2,586 CHALLENGER LTD 3,038 15,904 12,335 CHARTER HALL LONG WALE REIT 3,600 12,905 12,793 CHARTER HALL RETAIL REIT 148,478 395,662 422,150 CHARTER HALL SOCIAL INFRASTRUC 2,461 5,340 6,404 CIMIC GROUP LTD 409 6,668 6,072 COCHLEAR LTD 2,492