The Image of the Librarian in Film

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DOCTORAL (PHD) DISSERTATION by ANNA LUJZA SZÁSZ 2015

DOCTORAL (PHD) DISSERTATION by ANNA LUJZA SZÁSZ 2015 EMANCIPÁLT EMLÉKEZET KÉPES TÖRTÉNETEK A MAGYARORSZÁGI ROMA HOLOKAUSZT EMLÉKEZETRŐL írta SZÁSZ ANNA LUJZA KONZULENS: habil Dr. KOVÁCS ÉVA CSc EÖTVÖS LÓRÁND TUDOMÁNY EGYETEM, BUDAPEST TÁRSADALOMTUDOMÁNYI KAR SZOCIOLÓGIA TANSZÉK INTERDISZCIPLINÁRIS TÁRSADALOMKUTATÁSOK DOKTORI PROGRAM 2015 MEMORY EMANCIPATED EXPLORING THE MEMORY OF THE NAZI GENOCIDE OF ROMA IN HUNGARY by ANNA LUJZA SZÁSZ TUTOR: habil Dr. ÉVA KOVÁCS CSc EÖTVÖS LÓRÁND UNIVERSITY BUDAPEST FACULTY OF SOCIAL SCIENCES DEPARTMENT OF SOCIOLOGY INTERDISCIPLINARY SOCIAL STUDIES PROGRAM 2015 Acknowledgements As the submission of my dissertation was approaching I started getting emotional about it. It was the realization that this text is not only about the exploration of the memory of the Nazi genocide of Roma but it is also a context which made me possible to meet great people, to gain incredibly meaningful experience and knowledge academically, socially and personally, and to learn to be aware of the position from where I am speaking. It was a little bit more than four years of my life, and this project was developed, nurtured and completed together with many people whom I am thankful to and whom I shall keep in my memories. This research would have never begun if I had not met Júlia Szalai at a course titled “Sociological Approaches to Race and Ethnicity: The Roma in Post-communist Central Europe” at the Central European University in 2008. A year later I had the chance to be her research assistant in an FP7 research project on ethnic differences in education. I was in that privileged position that Júlia paved my way for many years and I immersed myself in the realm of her knowledge and enjoyed every bits and pieces of the work we did together. -

A4- What's New in Books.Pdf

Inside This Book (Are Three Books) by Barney Saltzberg Releasing April 2015, Recommended for ages 3-6 Three siblings create three books of their own using blank paper that they bind together (in descending sizes to match birth order, of course). One sibling’s work inspires the next, and so on, with each book’s text and art mirroring the distinct interests and abilities of its creator. Upon completion of their works, the siblings put one book inside the other, creating a new book to be read and shared by all! The Legends of Lake on the Mountain, by Roderick Bens (Leaders & Legacies series) – Recommended for boys grades 3 – 5 This series is surprisingly good with all of the fast paced elements that readers look for in a paranormal adventure story. This series is a great way to pique young readers’ Interest in Canadian history with notes in back that separate fact from fiction and provide more historical detail. I found myself Googling some of the events mentioned in this book to see if they really happened! Under the Pig Tree, by Margie Palatino, Releasing April 2015, Recommended for ages 3-6 The publisher and author of Under a Pig Tree seem to be having communication issues. The author has written a clear, no-nonsense history of figs. But the publisher is sure she meant pigs. After all, what’s the difference between two measly letters? What results is a hilarious illustrated history of pigs, from the earliest times (“Pigs were presented as ‘medals’ to the winners of the first Olympics”) to the present day (“There is nothing better than enjoying a cup of tea or glass of milk with one of those famous Pig Newtons”). -

Models of Time Travel

MODELS OF TIME TRAVEL A COMPARATIVE STUDY USING FILMS Guy Roland Micklethwait A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of The Australian National University July 2012 National Centre for the Public Awareness of Science ANU College of Physical and Mathematical Sciences APPENDIX I: FILMS REVIEWED Each of the following film reviews has been reduced to two pages. The first page of each of each review is objective; it includes factual information about the film and a synopsis not of the plot, but of how temporal phenomena were treated in the plot. The second page of the review is subjective; it includes the genre where I placed the film, my general comments and then a brief discussion about which model of time I felt was being used and why. It finishes with a diagrammatic representation of the timeline used in the film. Note that if a film has only one diagram, it is because the different journeys are using the same model of time in the same way. Sometimes several journeys are made. The present moment on any timeline is always taken at the start point of the first time travel journey, which is placed at the origin of the graph. The blue lines with arrows show where the time traveller’s trip began and ended. They can also be used to show how information is transmitted from one point on the timeline to another. When choosing a model of time for a particular film, I am not looking at what happened in the plot, but rather the type of timeline used in the film to describe the possible outcomes, as opposed to what happened. -

What's New on the Shelf Jake Epp Library

Jake Epp Library What’s New On The Shelf *= not published within the year, but new to our shelves Christian Fiction • Lone Star Standoff—Margaret Daley Adult Fiction • Little Cruelties—Liz Nugent • The Amish Sweet Shop • Fatal Threat—Valerie Hansen • Daylight—David Baldacci • Wyoming Ture—Diana Palmer • The String—Caleb Breakey • North Country Hero ; & North Country • Tender is the Flesh—Agustina Maria • Three Women Disappear: With a Bonus • The Christmas Swap—Melody Carlson Family—Lois Richer Bazterrica Novel: Come and Get Us—James Patterson • The Happy Camper—Melody Carlson • Danger on the Ranch—Dana Mentiink • The Good German—Dennis Bock • *Lovecraft Country—Matt Ruff • *The Victorian Christmas Brides Collection: 9 Women Dream of Perfect Christmases • Taken in Texas—Susan Sleeman • If I Had Your Face—Frances Cha • *Final Girls—Riley Sager During the Victorian Era • Mountain Peril • The Sentinel—Lee Child • Secret Santa—Andrew Shaffer • Rescuing His Secret Child—Maggie Black • War Lord—Bernard Cornwell • The Waiting Rooms—Eve Smith • Woman of Sunlight—Mary Connealy • Protecting His Secret Son—Laura Scott • *My Lady’s Choosing: An Interactive Ro- • Together by Christmas—Karen Swan • Her Secret Song—Mary Connealy • Secrets Resurfaced—Dana Mentink mance Novel—Kitty Curran • Cobble Hill—Cecily Von Ziegesar • Before I Called You Mine—Nicole Deese • Driftwood Dreams—T.I. Lowe • Fortune and Glory: Tantalizing Twenty- • The Cold Millions—Jess Walter • End Game—Rachel Dylan • Beach Haven—T.I. Lowe Seven—Janet Evanovich • White Ivy—Susie Yang -

2018 Annual Report

Annual Report 2018 Dear Friends, welcome anyone, whether they have worked in performing arts and In 2018, The Actors Fund entertainment or not, who may need our world-class short-stay helped 17,352 people Thanks to your generous support, The Actors Fund is here for rehabilitation therapies (physical, occupational and speech)—all with everyone in performing arts and entertainment throughout their the goal of a safe return home after a hospital stay (p. 14). nationally. lives and careers, and especially at times of great distress. Thanks to your generous support, The Actors Fund continues, Our programs and services Last year overall we provided $1,970,360 in emergency financial stronger than ever and is here for those who need us most. Our offer social and health services, work would not be possible without an engaged Board as well as ANNUAL REPORT assistance for crucial needs such as preventing evictions and employment and training the efforts of our top notch staff and volunteers. paying for essential medications. We were devastated to see programs, emergency financial the destruction and loss of life caused by last year’s wildfires in assistance, affordable housing, 2018 California—the most deadly in history, and nearly $134,000 went In addition, Broadway Cares/Equity Fights AIDS continues to be our and more. to those in our community affected by the fires and other natural steadfast partner, assuring help is there in these uncertain times. disasters (p. 7). Your support is part of a grand tradition of caring for our entertainment and performing arts community. Thank you Mission As a national organization, we’re building awareness of how our CENTS OF for helping to assure that the show will go on, and on. -

275. – Part One

275. – PART ONE 275. Clifford (1994) Okay, here’s the deal: I don’t know you, you don’t know me, but if you are anywhere near a television right now I need you to stop whatever it is that you’re doing and go watch “Clifford” on HBO Max. This is another film that has a 10% score on Rotten Tomatoes which just leads me to believe that all of the critics who were popular in the nineties didn’t have a single shred of humor in any of their non-existent funny bones. I loved this movie when I was seven, and I love it even more when I’m thirty-three. It’s genius. Martin Short (who at the time was forty-four) plays a ten-year-old hyperactive nightmare child from hell. I mean it, this kid might actually be the devil. He is straight up evil, conniving, manipulative and all-told probably causes no less than ten million dollars-worth of property damage. And, again, the plot is so simple – he just wants to go to Dinosaur World. There are so many comedy films with such complicated plots and motivations for their characters, but the simplistic genius of “Clifford” is just this – all this kid wants on the entire planet is to go to Dinosaur World. That’s it. The movie starts with him and his parents on an plane to Hawaii for a business trip, and Clifford knows that Dinosaur Land is in Los Angeles, therefore he causes so much of a ruckus that the plane has to make an emergency landing. -

Imitation of Life

Genre Films: OLLI: Spring 2021: weeks 5 & 6 week 5: IMITATION OF LIFE (1959) directed by Douglas Sirk; cast: Lana Turner, John Gavin, Sandra Dee, Juanita Moore, Susan Kohner, Dan O'Herlihy, Troy Donahue, Robert Alda Richard Brody: new yorker .com: “For his last Hollywood film, released in 1959, the German director Douglas Sirk unleashed a melodramatic torrent of rage at the corrupt core of American life—the unholy trinity of racism, commercialism, and puritanism. The story starts in 1948, when two widowed mothers of young daughters meet at Coney Island: Lora Meredith (Lana Turner), an aspiring actress, who is white, and Annie Johnson (Juanita Moore), a homeless and unemployed woman, who is black. The Johnsons move in with the Merediths; Annie keeps house while Lora auditions. A decade later, Lora is the toast of Broadway and Annie (who still calls her Miss Lora) continues to maintain the house. Meanwhile, Lora endures troubled relationships with a playwright (Dan O’Herlihy), an adman (John Gavin), and her daughter (Sandra Dee); Annie’s light-skinned teen-age daughter, Sarah Jane (Susan Kohner), is working as a bump-and-grind showgirl and passing as white, even as whites pass as happy and Annie exhausts herself mastering her anger and maintaining her self-control. For Sirk, the grand finale was a funeral for the prevailing order, a trumpet blast against social façades and walls of silence. The price of success, in his view, may be the death of the soul, but its wages afford retirement, withdrawal, and contemplation—and, upon completing the film, that’s what Sirk did.” Charles Taylor: villagevoice.com: 2015: “Fifty-six years after it opened, Douglas Sirk’s Imitation of Life … remains the apotheosis of Hollywood melodrama — as Sirk’s final film, it could hardly be anything else — and the toughest-minded, most irresolvable movie ever made about race in this country. -

2017 Annual Report

Annual 2017 Report Our ongoing investment into increasing services for the senior In 2017, The Actors Fund Dear Friends, members of our creative community has resulted in 1,474 senior and helped 13,571 people in It was a challenging year in many ways for our nation, but thanks retired performing arts and entertainment professionals served in to your generous support, The Actors Fund continues, stronger 2017, and we’re likely to see that number increase in years to come. 48 states nationally. than ever. Our increased activities programming extends to Los Angeles, too. Our programs and services With the support of The Elizabeth Taylor AIDS Foundation, The Actors Whether it’s our quick and compassionate response to disasters offer social and health services, Fund started an activities program at our Palm View residence in West ANNUAL REPORT like the hurricanes and California wildfires, or new beginnings, employment and training like the openings of The Shubert Pavilion at The Actors Fund Hollywood that has helped build community and provide creative outlets for residents and our larger HIV/AIDS caseload. And the programs, emergency financial Home (see cover photo), a facility that provides world class assistance, affordable housing 2017 rehabilitative care, and The Friedman Health Center for the Hollywood Arts Collective, a new affordable housing complex and more. Performing Arts, our brand new primary care facility in the heart aimed at the performing arts community, is of Times Square, The Actors Fund continues to anticipate and in the development phase. provide for our community’s most urgent needs. Mission Our work would not be possible without an engaged Board as well as the efforts of our top notch staff and volunteers. -

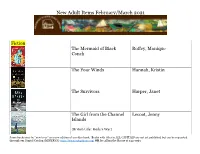

New Adult Items February/March 2021

New Adult Items February/March 2021 Fiction The Mermaid of Black Roffey, Monique Conch The Four Winds Hannah, Kristin The Survivors Harper, Janet The Girl from the Channel Lecoat, Jenny Islands (British title: Hedy’s War) Some books may be “new to us” or a new edition of an older book. Books with titles in ALL CAPITALS are not yet published but can be requested through our Digital Catalog (MINERVA) https://www.swhplibrary.org/ OR by calling the library at 244-7065 New Adult Items February/March 2021 Fiction The Shadow Box Rice, Luanne The Unwilling. Hart, John Milk Fed Broder, Melissa White Ivy Yang, Susie Some books may be “new to us” or a new edition of an older book. Books with titles in ALL CAPITALS are not yet published but can be requested through our Digital Catalog (MINERVA) https://www.swhplibrary.org/ OR by calling the library at 244-7065 New Adult Items February/March 2021 Fiction The Queen’s Gambit Tevis, Walter S. Klara and the Sun Ishiguro, Kazuo (author of Remains of the Day) The Prophets: a Novel Jones, Robert, Jr. The Paris Library Skeslien Charles, Janet Some books may be “new to us” or a new edition of an older book. Books with titles in ALL CAPITALS are not yet published but can be requested through our Digital Catalog (MINERVA) https://www.swhplibrary.org/ OR by calling the library at 244-7065 New Adult Items February/March 2021 Fiction Better Luck Next Time Johnson, Julia Claiborne My Year Abroad Lee, Chang-rae (Pulitzer Prize Finalist) The Power Couple Berenson, Alex Super Host Russo, Kate Some books may be “new to us” or a new edition of an older book. -

The Imitation of Life Activities Sara Jane: 1. in the Much Discussed Final

The Imitation of Life Activities Sara Jane: 1. In the much discussed final scene of Douglas Sirk's IMITATION OF LIFE (1959), Sara Jane Johnson (Susan Kohner) breaks through the crowd watching an extravagant funeral procession, pushes aside a policeman, and pulls open the doors of a horse-drawn hearse, crying, "I have killed my mother." a. How has Sara Jane “killed her mother”? b. How can this specific feeling of grief and regret impact the rest of her life? c. Although Annie Johnson loved her daughter dearly, was this love enough for Sara Jane? 2. Sara Jane challenges the limitations of' her identity. Refusing to be either a proper lady or a proper African-American/black girl, Sara Jane throughout the film enacts a series of "imitations". a. Identify 2 examples in which Sara Jane “pretends” or carries out some type of “imitation”. b. How does Annie Johnson feel about people pretending or being ashamed of who they are and where they come from? 3. Article about one of the characters from the original 1933 version of the movie. http://www.angelfire.com/jazz/ninamaemckinney/FrediWashington.html - anything but an imitation of life. 4. Memorable quotes from the movie. Select 2 quotes from any characters and write a 2-3 sentence response/reaction. What does the quote mean? How is it connected to the theme of the movie? Can you relate to the quote for a specific reason? Discuss any 2 quotes that stirred some type of reaction out of you (either good or bad). http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0052918/quotes a. -

Zerohack Zer0pwn Youranonnews Yevgeniy Anikin Yes Men

Zerohack Zer0Pwn YourAnonNews Yevgeniy Anikin Yes Men YamaTough Xtreme x-Leader xenu xen0nymous www.oem.com.mx www.nytimes.com/pages/world/asia/index.html www.informador.com.mx www.futuregov.asia www.cronica.com.mx www.asiapacificsecuritymagazine.com Worm Wolfy Withdrawal* WillyFoReal Wikileaks IRC 88.80.16.13/9999 IRC Channel WikiLeaks WiiSpellWhy whitekidney Wells Fargo weed WallRoad w0rmware Vulnerability Vladislav Khorokhorin Visa Inc. Virus Virgin Islands "Viewpointe Archive Services, LLC" Versability Verizon Venezuela Vegas Vatican City USB US Trust US Bankcorp Uruguay Uran0n unusedcrayon United Kingdom UnicormCr3w unfittoprint unelected.org UndisclosedAnon Ukraine UGNazi ua_musti_1905 U.S. Bankcorp TYLER Turkey trosec113 Trojan Horse Trojan Trivette TriCk Tribalzer0 Transnistria transaction Traitor traffic court Tradecraft Trade Secrets "Total System Services, Inc." Topiary Top Secret Tom Stracener TibitXimer Thumb Drive Thomson Reuters TheWikiBoat thepeoplescause the_infecti0n The Unknowns The UnderTaker The Syrian electronic army The Jokerhack Thailand ThaCosmo th3j35t3r testeux1 TEST Telecomix TehWongZ Teddy Bigglesworth TeaMp0isoN TeamHav0k Team Ghost Shell Team Digi7al tdl4 taxes TARP tango down Tampa Tammy Shapiro Taiwan Tabu T0x1c t0wN T.A.R.P. Syrian Electronic Army syndiv Symantec Corporation Switzerland Swingers Club SWIFT Sweden Swan SwaggSec Swagg Security "SunGard Data Systems, Inc." Stuxnet Stringer Streamroller Stole* Sterlok SteelAnne st0rm SQLi Spyware Spying Spydevilz Spy Camera Sposed Spook Spoofing Splendide -

Title: Conquering Information Literacy, Conan the Librarian Public Library

Title: Conquering Information Literacy, Conan the Librarian Public Library Audience: Public Library Patrons Grades 4th-7th Designers’ Names: Designed by Marie Cirelli, Gweneth Morton, and Andy Wolverton 1. Rationale for instruction: An information literate student can be defined as “one who accesses information efficiently and effectively, critically evaluates the information, and uses it accurately and creatively” (Grassian and Kaplowitz, 2009, p. 4). With the information explosion on the Internet, it is becoming more difficult and more important to be information literate. The public library can play a vital role in the education of its patrons by offering them the opportunity to learn and master the skills needed to be considered information literate. The mission of a public library is to provide information, support lifelong learning, and enrich the lives of its patrons. Based on experience with the patrons of the library and the mission of the library, an information literacy course for students in grades 4th-7th is being developed as a way to further support our patrons and meet the mission of the library. 2. Goal and objectives: Goal: The learner will understand how to search for and evaluate information from a variety of sources. Objective 1: The learner will apply the I-LEARN model. Objective 2: The learner will locate appropriate sources using the Internet and OPAC. Objective 3: The learner will apply the previously found information. Overview 1. Brief summary of unit: The unit is a three-day program in which students learn how to search for and evaluate information from a variety of sources. The program is structured for a younger age group and focuses on hands-on learning and immediate feedback.