Christian Education in the Stone-Campbell Movement

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CHRISTIAN MESSENGER INDEX Edited by Barry Jones Contributors

CHRISTIAN MESSENGER INDEX edited by Barry Jones Contributors Warren · Baldwin Roderick Chestnut Charles Dorsey* Mark Jam-eson Barry Jones Jesse Kirkham *compiled scripture index wrote introduc~ion Word ·Processing by Jean Saunders II II I .. TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE I. INTRODUCTION . .• • • . •· . .. • 1-11 II. INDEX . o .. • . • • . 0 • • • • 0 1-108 A-Z • • • • . .. •: .. ! • • .• • 1-84 Pseudonyms • • • • • • 85-86 Scriptures· • .. ~ . 0 • .. • • . • 0 0 .. • .. 87-108 ·.. I I INTRODUCTION Barton W. Stone and the Christian Messenger No study of the restoration movement would b.e complete without the Christian Messenger. This periodical "was a reflection of the heart of its .editor .. l Barton W. ' Stone. While Stone's popularity has been somewhat over shadowed by Alexander. Campbell in the study of the restor ation movement, he nevertheless exerted great. influence in his own day for the return of New Testament Christianity. Upon recei~ing the news of Stone's death T. J. Matlock wrote, "I have for a long time regarded him as the moderator of this whole reformation."2 Similarly, Tolbert Fanning wrote, · "If justice is ever done to his memory, he ~ill be regard .. ) ed as the first great American reformer • • • Barton Warren Stone was born·near Port Tobacco, Maryland on Thursday, December 24, 1772. He died at Han nibal, Missouri in the home of his daughter, Amanda Bowen:, November 9, 1844. He was first buried on his farm near .1James DeForest Murch, Christians Only (Cincinnati: Standard Publishing Co., 1962), p. 92. 2T. J. Matlock, "Letter," Christian Messenger 14 (December 1844):254. )Tolbert Fanning, "A Good Man Has Fallen," Christ ian Review 1 (December 1844) : 288 .• 1 . -

Enter Your Title Here in All Capital Letters

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by K-State Research Exchange THE BATTLE CRY OF PEACE: THE LEADERSHIP OF THE DISCIPLES OF CHRIST MOVEMENT DURING THE AMERICAN CIVIL WAR, 1861-1865 by DARIN A.TUCK B. A., Washburn University, 2007 A THESIS submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree MASTER OF ARTS Department of History College of Arts and Sciences KANSAS STATE UNIVERSITY Manhattan, Kansas 2010 Approved by: Major Professor Robert D. Linder Copyright DARIN A. TUCK 2010 Abstract As the United States descended into war in 1861, the religious leaders of the nation were among the foremost advocates and recruiters for both the Confederate and Union forces. They exercised enormous influence over the laity, and used their sermons and periodicals to justify, promote, and condone the brutal fratricide. Although many historians have focused on the promoters of war, they have almost completely ignored the Disciples of Christ, a loosely organized religious movement based on anti-sectarianism and primitive Christianity, who used their pulpits and periodicals as a platform for peace. This study attempts to merge the remarkable story of the Disciples peace message into a narrative of the Civil War. Their plea for nonviolence was not an isolated event, but a component of a committed, biblically-based response to the outbreak of war from many of the most prominent leaders of the movement. Immersed in the patriotic calls for war, their stance was extremely unpopular and even viewed as traitorous in their communities and congregations. This study adds to the current Disciples historiography, which states that the issue of slavery and the Civil War divided the movement North and South, by arguing that the peace message professed by its major leaders divided the movement also within the sections. -

Christian Unity in Stone-Campbell Movement

M. Horvatek: New Testament Paradigm of the Unity of Christians Christian Unity in Stone-Campbell Movement Douglas A. FOSTER Abilene Christian University, USA UDK: 261.8 Original scientific paper Received: February 15, 2008. Accepted: March 15, 2008. Abstract Author offers review of the backgrounds to Stone-Campbell concepts of Christian unity, insides on the early unity impulse in the Stone-Camp- bell Movement, as well as the development of the idea of unity in the Post-Bellum Period. A valuable explanation is offered on the twentieth- century understandings of unity in the Three Streams, and on the efforts at internal unity in the Stone-Campbell Movement. Introduction In the western church the divisions resulting from the Protestant Reformation became a source of deep concern for some leaders. Lutheran Philipp Melanch- thon proposed compromise in the area of adiaphora, indifferent or non-essential matters, if it would maintain the church’s visible unity. George Calixtus suggested that only heresy, defined as denial of an essential truth of Christianity believed by the church in the first five centuries, could be the basis for breaking fellow- ship. Calvin and other Reformed theologians insisted that the true church was invisible, ultimately known only to God, thus lessening the severity of the visible divisions. I. Backgrounds to Stone-Campbell Concepts of Christian Unity The transplanting of European Christianity to America exacerbated its divisions as religious freedom led to schism in existing bodies and the creation of new ones. For many Americans the developing system of denominationalism appeared to be the desired and normal condition of the church. -

What Kind of Church Is This?

WHY I BELONG T O T HE C HRISTIA N C HURC H I STAYI NG C ONNE CT ED I B EYON D S LOG ANS ® RESOURCING CHRISTIAN CHURCHES SPECIAL EDITION What kind of church is this? www.christianstandard.com What kind of church is this? BY LEROY LAWSON One thing is certain—there is no shortage of churches. You can take your pick among the hundreds of different kinds, from the proud old denominations like the Episcopalian and Presbyterian to the newer, more energetic Assembly of God or Seventh Day Adventists, to say nothing of those amazingly numerous and various cults that keep springing up. In the midst of such diversity, what is special about our church? What kind of a church is it, anyway? A Paradox and a Challenge Our Roots We answer paradoxically. !e distinc- Christian churches and churches of tive about this Christian church is that it Christ trace their modern origins to the has no distinctives. In fact we deliberately early 19th-century American frontier, a seek not to be di#erent, because our goal period of militancy among denominations. Barton W. Stone, some Presbyterian leaders is unity, not division. Christianity has America’s pioneers brought their deeply in Kentucky published e Last Will and su#ered long enough from deep divi- rooted religious convictions to the new Testament of the Spring#eld Presbytery , sions separating denomination from de- land and perpetuated their old animosities. putting to death their denominational nomination, Christian from Christian. Presbyterian squared o# against Anglican connections. !ey said, “We will, that When Jesus prayed “that all of them may who defended himself against Baptist who this body die, be dissolved, and sink into be one, Father, just as you are in me and I had no toleration for Lutheran. -

Oliver Cowdery's 1835 Response to Alexander Campbell's 1831 "Delusions"

Oliver Cowdery's 1835 Response to Alexander Campbell's 1831 "Delusions" John W. Welch All his life, Richard Lloyd Anderson has set an important example for many Latter-day Saint scholars and students. His emphasis on documentary research—locating and analyzing the best primary sources—has become the hallmark of his scholarship, with respect to both the New Testament and early Mormon history. As an undergraduate and graduate student in his ancient history and Greek New Testament classes, I learned rsthand to appreciate his skills in working with texts, in forensically evaluating claims of various scholars, and in providing substantial arguments in support of the commonsense, mainstream views of the central events in the history of the church from the time of Christ to the era of Joseph Smith. The present study deals with a little-known editorial written by Oliver Cowdery in the 1830s.1 By contributing to this volume in Richard Anderson’s honor, I hope to pay tribute to him, to his attention to historical documents, and to his devoted defenses of the characters and concepts that are crucial to the restoration of the gospel in these the latter days. The First Substantive Attack on the Book of Mormon As early as February 1831, a barrage of incendiary criticisms against the Book of Mormon was published by a Baptist minister, greeting the rst of the Saints as they moved into the Kirtland, Ohio, area. The author of that onslaught was Alexander Campbell (1788–1866), a potent preacher, lecturer, and philosopher who took part in contemporary debates; -

Journalism's Deep Roots in the Stone-Campbell Movement

Journal of Discipliana Volume 74 Issue 1 Journal of Discipliana Volume 74 Article 2 2021 Journalism’s Deep Roots in the Stone-Campbell Movement John M. Imbler Phillips Theological Seminary, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.discipleshistory.org/journalofdiscipliana Part of the Christian Denominations and Sects Commons, History of Christianity Commons, and the Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons Recommended Citation Imbler, John M. (2021) "Journalism’s Deep Roots in the Stone-Campbell Movement," Journal of Discipliana: Vol. 74 : Iss. 1 , Article 2. Available at: https://digitalcommons.discipleshistory.org/journalofdiscipliana/vol74/iss1/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ Disciples History. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Discipliana by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ Disciples History. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Imbler: Journalism’s Deep Roots in the Stone-Campbell Movement Journalism’s Deep Roots in the Stone-Campbell Movement John M. Imbler As the recently constituted nation was expanding beyond the settled northeast, in- formation on a variety of subjects was carried by an increasing number of newly estab- lished local presses. Presidential historian Doris Kearns Goodwin observes, “With few public entertainments in rural America (c. 1850s), villages and farmers regarded the spo- ken word and political debates as riveting spectator sports.” She continues, “Following such debates, the dueling remarks were regularly printed in their entirety in newspapers then reprinted in pamphlet form…where they provoked discourse over a wide space and prolonged time.”1 While her analysis refers to the general population, it also reflects the character of the Stone-Campbell people who were heavily invested in publications. -

Stone-Campbell Biography Edwin R. Errett: Martyr to a Lost Cause

Leaven Volume 7 Issue 1 Missions and the Church Article 21 1-1-1999 Stone-Campbell Biography Edwin R. Errett: Martyr to a Lost Cause Henry Webb Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.pepperdine.edu/leaven Part of the Biblical Studies Commons, Christianity Commons, and the Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons Recommended Citation Webb, Henry (1999) "Stone-Campbell Biography Edwin R. Errett: Martyr to a Lost Cause," Leaven: Vol. 7 : Iss. 1 , Article 21. Available at: https://digitalcommons.pepperdine.edu/leaven/vol7/iss1/21 This Biography is brought to you for free and open access by the Religion at Pepperdine Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Leaven by an authorized editor of Pepperdine Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected], [email protected]. Webb: Stone-Campbell Biography Edwin R. Errett: Martyr to a Lost Cause 48 Leaven, Winter, 1999 Stone-Campbell Biography EDWIN R. ERRETT: Martyr to a Lost Cause Henry Webb Edwin R. Errett, editor of the writer of Bible school materials, and a conservative institution for ministe- Christian Standard from 1929 until his in the latter year he was made editor- rial education, the Cincinnati Bible death in 1944, is known primarily for in-chief of all Bible school publica- Institute. When that school was merged the leadership he provided to Christian tions. In 1929 he was named editor of with McGarvey Bible Institute in 1924 Churches/Churches of Christ during a the Christian Standard. For the next to form Cincinnati Bible Seminary, critical period in their history. -

Periodicals of the Disciples of Christ and Related Religious Groups

Disciples of Christ Historical Society Digital Commons @ Disciples History Stone-Campbell Movement Periodical Indexes 1943 Periodicals of the Disciples of Christ and Related Religious Groups Claude E. Spencer Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.discipleshistory.org/all_periodical_indexes PERIODICALS OF The Disciples of Christ SPENCER " NORTH CAROLINA HRISTIAN MISSIONARY CONVENTION C.C.WARE WILSON.N.C. Jlvcnivist !1iW iPii^PHiii PERIODICALS of the DISCIPLES OF CHRIST and RELATED RELIGIOUS GROUPS compiled by Claude E. Spencer Disciples of Christ Historical Society- Canton,, Missouri 1943 DISCIPLIANA LIBRARY CHRISTIAN COLLEGE «5 ^3 jp ATLANTIC WILSON, N. C. Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2013 http://archive.org/details/periodicalsofdisOOclau DISCIPLES OF CHRIST HISTORICAL SOCIETY OFFICERS J, Edward Moseley President W, H. Hanna Vice-president A. T. DeGroot Secretary- treasurer Claude E. Spencer Curator EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE Term Expiring 1943 Term Expiring 1944 Warner Muir W. H. Hanna Merl R. Eppse A. T. DeGroot Walter C. G-ibbs Edgar C. Riley Richard L. James W. E, Garrison George N. Mayhew Eva Jean Wrather Stephen J. England Claude E, Spencer James DeForest Murch J, Edward Moseley Term Expiring 1945 C. C. Ware Colby D. Hall Henry K. Shaw Enos E. Dowling Reuben Butchart Mrs. W. D. Barnhart Dwight E. Stevenson - li- FORWORD Periodicals of the Disciples of Christ and related reli gious groups, made possible through the cooperation of Culver- Stockton college with the Disciples of Christ Historical Society, is the first attempt at a comprehensive list of the periodicals of the Disciples of Christ, the Christian church, and the churches of Christ. In this work I have attempted to list the title of every periodical designed for more than individual church circulation. -

Churches of Christ and Christian Churches in Early Oregon, 1842-1882 Jerry Rushford Pepperdine University

Pepperdine University Pepperdine Digital Commons Churches of Christ Heritage Center Jerry Rushford Center 1-1-1998 Christians on the Oregon Trail: Churches of Christ and Christian Churches in Early Oregon, 1842-1882 Jerry Rushford Pepperdine University Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.pepperdine.edu/heritage_center Part of the Christianity Commons Recommended Citation Rushford, Jerry, "Christians on the Oregon Trail: Churches of Christ and Christian Churches in Early Oregon, 1842-1882" (1998). Churches of Christ Heritage Center. Item 5. http://digitalcommons.pepperdine.edu/heritage_center/5 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Jerry Rushford Center at Pepperdine Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Churches of Christ Heritage Center by an authorized administrator of Pepperdine Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CHRISTIANS About the Author ON THE Jerry Rushford came to Malibu in April 1978 as the pulpit minister for the University OREGON TRAIL Church of Christ and as a professor of church history in Pepperdine’s Religion Division. In the fall of 1982, he assumed his current posi The Restoration Movement originated on tion as director of Church Relations for the American frontier in a period of religious Pepperdine University. He continues to teach half time at the University, focusing on church enthusiasm and ferment at the beginning of history and the ministry of preaching, as well the nineteenth century. The first leaders of the as required religion courses. movement deplored the numerous divisions in He received his education from Michigan the church and urged the unity of all Christian College, A.A. -

The Relationship Between James A. Garfield and the Disciples of Christ" (1977)

Pepperdine University Pepperdine Digital Commons Churches of Christ Heritage Center Jerry Rushford Center 8-1-1977 Political Disciple: The Relationship Between James A. Garfield nda the Disciples of Christ Jerry Rushford Pepperdine University Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.pepperdine.edu/heritage_center Part of the Christianity Commons Recommended Citation Rushford, Jerry, "Political Disciple: The Relationship Between James A. Garfield and the Disciples of Christ" (1977). Churches of Christ Heritage Center. Item 7. http://digitalcommons.pepperdine.edu/heritage_center/7 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Jerry Rushford Center at Pepperdine Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Churches of Christ Heritage Center by an authorized administrator of Pepperdine Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. From the Personal Library of Jerry Rushford Escomb Saxon Church, County Durham, England. Built c. A.D, 670 UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Santa Barbara Po litic a l Disciple: The Relationship Between James A. Garfield and the Disciples of C hrist A Dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Religion in America by Jerry Bryant Rushford Committee in charge: Professor Robert Michaelsen, Chairman Professor Roderick Nash Professor Carl V. Harris August 1977 The dissertation of Jerry Bryant Rushford is approved: August 1977 PUBLICATION OPTION I hereby reserve a ll rights of publication, including the right to reproduce this disser tation, in any form for a period of three years from the date of submission. Sig n e d FOR L O R I, who sha re d i t a l l iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I want to thank members of the sta ffs of the follow ing institutions for their help in locating materials: the Williams College Library, Williamstown, Massachusetts; the Manuscript Division of the Library of Congress; the Bethany College Library, Bethany, West Virginia; the Hiram College Library, Hiram, Ohio; the James A. -

By David R. Kenney I Highly Respect Alexander

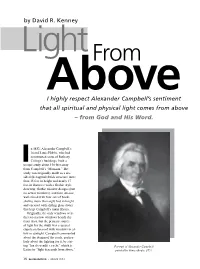

by David R. Kenney Light AboveFrom I highly respect Alexander Campbell’s sentiment that all spiritual and physical light comes from above – from God and His Word. n 1832, Alexander Campbell’s friend Louis Hobbs, who had constructed some of Bethany College’s buildings, built a Iunique study about 150 feet away from Campbell’s “Mansion.” The study was originally made as a six- sided (hexagonal) brick structure more than 15 feet in height and nearly 17 feet in diameter with a Gothic-style doorway, Gothic window designs (but no actual windows), and four interior walls lined with four sets of book- shelves more than eight feet in height and encased with sliding glass doors that kept Campbell’s main library. Originally, the only windows were the two narrow windows beside the front door, but the primary source of light for the study was a special cupola on the roof with windows to al- low in sunlight. Campbell commented about the design of the study, particu- larly about the lighting for it, by stat- ing “lux descendit e caelo,” which is Portrait of Alexander Campbell Latin for “light descends from above.” painted by James Bogle, 1857. 38 Gospel advocate • March 2013 It is reported that he would state that all light, physical and spiritual, comes from above, so he wanted to harness this “light from above” for his study. Campbell was often referred to as “the sage of Bethany,” a title he certainly earned. He was a serious student of the Scriptures. When he was under his father’s training for ministry, Campbell followed a study regimen that he maintained throughout his life: “Arrangement for studies for winter of 1810. -

A Basic Bibliography of the Stone-Campbell Movement the Best Single Resource Is Doug Foster, Paul Blowers, and D

A Basic Bibliography of the Stone-Campbell Movement The best single resource is Doug Foster, Paul Blowers, and D. Newell Williams, eds. The Encyclopedia of the Stone-Campbell Movement. Grand Rapids: William B. Eerdmans, 2005. Its articles cover most major leaders, ministers, theologians, institutions and organizations. There are numerous illustrations and short bibliographies direct readers to additional resources. State, Regional and Local Histories are too numerous to list; inquire at DCHS. Below are basic overview histories from each of the three main streams of the movement: Christian Church (Disciples of Christ): Mark Toulouse, Joined in Discipleship: The Shaping of Contemporary Disciples Identity. rev. ed. Chalice Press: St. Louis, 1997. Lester G. McAllister and William E. Tucker, Journey in Faith: A History of the Christian Church (Disciples of Christ). Bethany Press: St. Louis, 1975. Yearbooks for Christian Churches and Disciples published annually since 1889 list ministers, congregations and organizations. Christian Churches and Churches of Christ: Henry E. Webb, In Search of Christian Unity: A History of the Restoration Movement. Cincinnati: Standard Publishing, 1990 Dennis Helsabeck has a forthcoming brief history to be published this spring by Leafwood Publishers, Abilene, TX. www.leafwoodpublishers.com Directory of the Ministry for Christian Churches and Churches of Christ published annually since 1955. It lists ministers, congregations and para-church ministries. Churches of Christ: Richard T. Hughes, Reviving the Ancient Faith: The Story of Churches of Christ in America. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1996. David Edwin Harrell, Jr. The Churches of Christ in the Twentieth Century: Homer Hailey’s Personal Journey of Faith. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2000.