Arxiv:1809.05035V1 [Quant-Ph] 12 Sep 2018 Bulgaria

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Decays of an Exotic 1-+ Hybrid Meson Resonance In

PHYSICAL REVIEW D 103, 054502 (2021) Decays of an exotic 1 − + hybrid meson resonance in QCD † ‡ ∥ Antoni J. Woss ,1,* Jozef J. Dudek,2,3, Robert G. Edwards,2, Christopher E. Thomas ,1,§ and David J. Wilson 1, (for the Hadron Spectrum Collaboration) 1DAMTP, University of Cambridge, Centre for Mathematical Sciences, Wilberforce Road, Cambridge CB3 0WA, United Kingdom 2Thomas Jefferson National Accelerator Facility, 12000 Jefferson Avenue, Newport News, Virginia 23606, USA 3Department of Physics, College of William and Mary, Williamsburg, Virginia 23187, USA (Received 30 September 2020; accepted 23 December 2020; published 10 March 2021) We present the first determination of the hadronic decays of the lightest exotic JPC ¼ 1−þ resonance in lattice QCD. Working with SU(3) flavor symmetry, where the up, down and strange-quark masses approximately match the physical strange-quark mass giving mπ ∼ 700 MeV, we compute finite-volume spectra on six lattice volumes which constrain a scattering system featuring eight coupled channels. Analytically continuing the scattering amplitudes into the complex-energy plane, we find a pole singularity corresponding to a narrow resonance which shows relatively weak coupling to the open pseudoscalar– pseudoscalar, vector–pseudoscalar and vector–vector decay channels, but large couplings to at least one kinematically closed axial-vector–pseudoscalar channel. Attempting a simple extrapolation of the couplings to physical light-quark mass suggests a broad π1 resonance decaying dominantly through the b1π 0 mode with much smaller decays into f1π, ρπ, η π and ηπ. A large total width is potentially in agreement 0 with the experimental π1ð1564Þ candidate state observed in ηπ, η π, which we suggest may be heavily suppressed decay channels. -

High-Resolution Infrared Spectroscopy: Jet-Cooled Halogenated Methyl Radicals and Reactive Scattering Dynamics in an Atom + Polyatom System

HIGH-RESOLUTION INFRARED SPECTROSCOPY: JET-COOLED HALOGENATED METHYL RADICALS AND REACTIVE SCATTERING DYNAMICS IN AN ATOM + POLYATOM SYSTEM by ERIN SUE WHITNEY B.A., Williams College, 1996 A thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Colorado in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry 2006 UMI Number: 3207681 Copyright 2006 by Whitney, Erin Sue All rights reserved. UMI Microform 3207681 Copyright 2006 by ProQuest Information and Learning Company. All rights reserved. This microform edition is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest Information and Learning Company 300 North Zeeb Road P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, MI 48106-1346 This thesis for the Doctor of Philosophy degree entitled: High resolution infrared spectroscopy: Jet cooled halogenated methyl radicals and reactive scattering dynamics in an atom + polyatom system written by Erin Sue Whitney has been approved for the Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry by David J. Nesbitt Veronica M. Bierbaum Date ii Whitney, Erin S. (Ph.D., Chemistry) High-Resolution Infrared Spectroscopy: Jet-cooled halogenated methyl radicals and reactive scattering dynamics in an atom + polyatomic system Thesis directed by Professor David J. Nesbitt. This thesis describes a series of projects whose common theme comprises the structure and internal energy distribution of gas-phase radicals. In the first two projects, shot noise-limited direct absorption spectroscopy is combined with long path-length slit supersonic discharges to obtain first high-resolution infrared spectra for jet-cooled CH2F and CH2Cl in the symmetric and antisymmetric CH2 stretching modes. -

The Acetylene Ground State Saga Michel Herman

The acetylene ground state saga Michel Herman To cite this version: Michel Herman. The acetylene ground state saga. Molecular Physics, Taylor & Francis, 2008, 105 (17-18), pp.2217-2241. 10.1080/00268970701518103. hal-00513123 HAL Id: hal-00513123 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-00513123 Submitted on 1 Sep 2010 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Molecular Physics For Peer Review Only The acetylene ground state saga Journal: Molecular Physics Manuscript ID: TMPH-2007-0155 Manuscript Type: Invited Article Date Submitted by the 30-May-2007 Author: Complete List of Authors: Herman, Michel; Université Libre de Bruxelles, Chimie quantique et Photophysique acetylene, global picture, high resolution spectroscopy, Keywords: instrumental developments, intramolecular dynamics URL: http://mc.manuscriptcentral.com/tandf/tmph Page 1 of 93 Molecular Physics 1 2 3 4 11 July 2010 5 Invited Manuscript 6 7 8 9 10 The acetylene ground state saga 11 12 13 14 15 Michel HERMAN 16 ServiceFor de PeerChimie quantique Review et Photophysique, Only CP 160/09 17 18 Université libre de Bruxelles (U.L.B.) 19 Ave. Roosevelt, 50. 20 21 B-1050 22 Brussels 23 24 Belgium 25 26 27 [email protected] 28 29 30 Pages : 57 31 32 Figures : 32 (including 2 colour figures) 33 Tables : 3 34 35 36 This ms was written using ‘‘century schoolbook’’ and, whenever necessary, 37 38 ‘‘symbol’’ fonts. -

The First Physics Picture of Contractions from a Fundamental Quantum Relativity Symmetry Including All Known Relativity Symmetri

NCU-HEP-k071 Feb. 2018 ed. Mar. 2019 The First Physics Picture of Contractions from a Fundamental Quantum Relativity Symmetry Including all Known Relativity Symmetries, Classical and Quantum Otto C. W. Kong, Jason Payne Department of Physics and Center for High Energy and High Field Physics, National Central University, Chung-li, Taiwan 32054 Abstract In this article, we utilize the insights gleaned from our recent formulation of space(-time), as well as dynamical picture of quantum mechanics and its classical approximation, from the relativity symmetry perspective in order to push further into the realm of the proposed fundamental relativity symmetry SO(2, 4). The latter has its origin arising from the perspectives of Planck scale deformations of relativity symmetries. We explicitly trace how the diverse actors in this story change through various contraction limits, paying careful attention to the relevant physical units, in order to place all known relativity theories – quantum and classical – within a single framework. More specifically, we explore both of the possible contractions of SO(2, 4) and its coset spaces in order to determine how best to recover the lower-level theories. These include both new models and all familiar theories, as well as quantum and classical dynamics with and without Einsteinian special arXiv:1802.02372v2 [hep-th] 12 Jan 2021 relativity. Along the way, we also find connections with covariant quantum mechanics. The emphasis of this article rests on the ability of this language to not only encompass all known physical theories, but to also provide a path for extensions. It will serve as the basic background for more detailed formulations of the dynamical theories at each level, as well as the exact connections amongst them. -

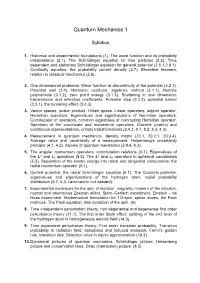

Quantum Mechanics 1

Quantum Mechanics 1 Syllabus 1. Historical and experimental foundations (1). The wave function and its probability interpretation (2.1). The Schrödinger equation for free particles (2.2). Time dependent and stationary Schrödinger equation for general potential (2.5.1,2.8.1). Continuity equation, the probability current density (2.7). Ehrenfest theorem, relation to classical mechanics (2.6). 2. One dimensional problems: Wave function at discontinuity of the potential (3.2.1). Potential well (3.4). Harmonic oscillator: algebraic method (3.1.1), Hermite polynomials (3.1.2), zero point energy (3.1.3). Scattering in one dimension: transmission and reflection coefficients. Potential step (3.2.2), potential barrier (3.3.1), the tunneling effect (3.3.3). 3. Vector spaces, scalar product, Hilbert space. Linear operators, adjoint operator, Hermitian operators. Eigenvalues and eigenfunctions of Hermitian operators. Commutator of operators, common eigenbasis of commuting Hermitian operator. Spectrum of the coordinate and momentum operators. Discrete (matrix) and continuous representations, unitary transformations (2.4.3, 8.1, 8.2, 8.3, 4.3). 4. Measurement in quantum mechanics, density matrix (20.1, 20.2.1, 20.3.4). Average value and uncertainty of a measurement. Heisenberg’s uncertainty principle (4.1, 4.2). Axioms of quantum mechanics (2.9.4, 8.3). 5. The angular momentum operators, commutation relations (5.1). Eigenvalues of 2 2 the L and Lz operators (5.2). The L and Lz operators in spherical coordinates (5.3). Separation of the kinetic energy into radial and tangential components: the radial momentum operator (6.1). 6. Central potential, the radial Schrödinger equation (6.1). -

Quantum Field Theory Without a Vacuum

EJTP 14, No. 37 (2018) 1{20 Electronic Journal of Theoretical Physics Projective Limits of State Spaces: Quantum Field Theory Without a Vacuum Suzanne Lan´ery∗ Centro de Ciencias Matem´aticas, Universidad Nacional Aut´onomade M´exico, Apartado Postal 61-3, 58089 Morelia, Michoac´an,M´exico Received 27 December 2017, Accepted 16 March 2018, Published 20 April 2018 Abstract: Instead of formulating the states of a Quantum Field Theory (QFT) as density matrices over a single large Hilbert space, it has been proposed by Kijowski [20] to construct them as consistent families of partial density matrices, the latter being defined over small 'building block' Hilbert spaces. In this picture, each small Hilbert space can be physically interpreted as extracting from the full theory specific degrees of freedom. This allows to reduce the quantization of a classical field theory to the quantization of finite-dimensional sub-systems, thus sidestepping some of the common ambiguities (specifically, the issues revolving around the choice of a 'vacuum state'), while obtaining robust and well-controlled quantum states spaces.The present letter provides a self-contained introduction to this formalism, detailing its motivations as well as its relations to other approaches to QFT (such as conventional Fock-like Hilbert spaces, path-integral quantization, and the algebraic formulation). At the same time, it can serve as a reading guide to the series of more in-depth articles [27, 28, 29, 30]. c Electronic Journal of Theoretical Physics. All rights reserved. Keywords: Quantum Field Theory; Vacuum States; Inequivalent Representations; Geometric Quantization; Projective Limits; Algebras of Observables PACS (2010): 02.40.Yy; 03.50.-z; 03.70.+k; 04.62.+v; 04.60.Ds 1. -

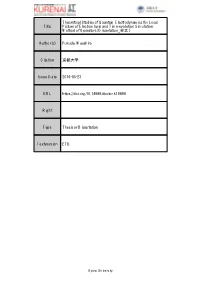

Title Theoretical Studies of Quantum Electrodynamics for Local Picture Of

Theoretical Studies of Quantum Electrodynamics for Local Title Picture of Electron Spin and Time-evolution Simulation Method of Operators( Dissertation_全文 ) Author(s) Fukuda, Masahiro Citation 京都大学 Issue Date 2016-05-23 URL https://doi.org/10.14989/doctor.k19896 Right Type Thesis or Dissertation Textversion ETD Kyoto University Theoretical Studies of Quantum Electrodynamics for Local Picture of Electron Spin and Time-evolution Simulation Method of Operators Masahiro Fukuda 2016 Theoretical Studies of Quantum Electrodynamics for Local Picture of Electron Spin and Time-evolution Simulation Method of Operators Masahiro Fukuda Department of Micro Engineering Kyoto University 2016 Contents General Introduction 4 I Theoretical Studies of Local Picture of Electron Spin in Quan- tum Electrodynamics 9 1 Local Physical Quantities for Spin Based on the Relativistic Quantum Field Theory in Molecular Systems 10 1.1 Introduction . 10 1.2 Theory . 12 1.2.1 Spin vorticity theory . 12 1.2.2 Zeta potential and spatial symmetry . 15 1.2.3 Local picture change errors . 16 1.2.4 Two-component expressions of the local physical quantities . 17 1.3 Computational details . 19 1.4 Results and Discussion . 20 1.5 Conclusions . 26 2 Local Spin Dynamics with the Electron Electric Dipole Moment 35 2.1 Introduction . 35 2.2 Theory . 37 2.2.1 Hamiltonian density with EDM . 37 2.2.2 Spin precession with EDM . 38 2.2.3 The effective electric field for the electron EDM . 39 2.2.4 Local spin torque dynamics with EDM . 41 1 2.3 Computational details . 43 2.4 Results and Discussion . 45 2.5 Conclusions . -

Axiomatic Quantum Mechanics: Necessity and Benefits for The

Axiomatic quantum mechanics: Necessity and benefits for the physics studies Jasmina Jekni´c-Dugi´c University of Niˇs, Faculty of Science and Mathematics, 18000 Niˇs, Serbia Momir Arsenijevi´c University of Kragujevac, Faculty of Science, 34000 Kragujevac, Serbia Miroljub Dugi´c∗ University of Kragujevac, Faculty of Science, 34000 Kragujevac, Serbia (Dated: November 7, 2017) Abstract The ongoing progress in quantum theory emphasizes the crucial role of the very basic principles of quantum theory. However, this is not properly followed in teaching quantum mechanics on the graduate and undergraduate levels of physics studies. The existing textbooks typically avoid the axiomatic presentation of the theory. We emphasize usefulness of the systematic, axiomatic approach to the basics of quantum theory as well as its importance in the light of the modern scientific-research context. arXiv:1711.00268v2 [physics.ed-ph] 5 Nov 2017 1 1. Introduction Even a brief search on the Internet reveals a significant delay in the textbook presentation of the basics of quantum mechanics relative to the recent and ongoing, considerable scien- tific and technological progress that is based on the basic principles of quantum mechanics, e.g. [1-3]. New reading and reconsideration of the basic postulates of quantum mechanics generate and accumulate the knowledge that should be properly presented on the graduate or undergraduate physics studies. According to the data available on the Internet, by far the most of the most-used graduate/undergraduate-level textbooks poorly present the axiomatic and methodological character of quantum mechanics. Plenty of the textbooks clearly serve the purposes of ap- plication e.g. -

Quantum Mechanics Wave Function Some Trajectories of a Harmonic Oscillator

Quantum Mechanics_ wave function Some trajectories of a harmonic oscillator (a ball attached to aspring) in classical mechanics (A–B) and quantum mechanics (C–H). In quantum mechanics (C–H), the ball has a wave function, which is shown with real part in blue and imaginary part in red. The trajectories C, D, E, F, (but not G or H) are examples ofstanding waves, (or "stationary states"). Each standing wave frequency is proportional to a possible energy level of the oscillator. This "energy quantization" does not occur in classical physics, where the oscillator can have any energy. A wave function or wavefunction (also named a state function) in quantum mechanics describes the quantum state of a system of one or more particles, and contains all the information about the system. Quantities associated with measurements, like the average momentum of a particle, are derived from the wavefunction. Thus it is a central quantity in quantum mechanics. The most common symbols for a wave function are the Greek letters ψ or Ψ (lower-case and capital psi). The Schrödinger equation determines how the wave function evolves over time, that is, the wavefunction is the solution of the Schrödinger equation. The wave function behaves qualitatively like other waves, like water waves or waves on a string, because the Schrödinger equation is mathematically a type ofWave equation. This explains the name "wave function", and gives rise to wave–particle duality. The wave function for a given system does not have a unique representation. Most commonly, it is taken to be a function of all the position coordinates of the particles and time, that is, the wavefunction is in "position space". -

Complex Dynamics of Real Quantum, Classical and Hybrid Micro-Machines

Complex Dynamics of Real Quantum, Classical and Hybrid Micro-Machines A.P. KIRILYUK* Institute of Metal Physics, Kiev, Ukraine ABSTRACT. Any real interaction process produces many equally possi- ble, but mutually incompatible system versions, or realisations, giving rise to the omnipresent, purely dynamic randomness (chaoticity) and universal- ly defined complexity (sections 3-4). Since quantum behaviour dynamical- ly emerges as the lowest level of unreduced world complexity (sections 4.6-7, 5.3), quantum interaction randomness can only be relatively strong (explicit), which reveals the causal origin of quantum indeterminacy (sec- tions 4.6.1, 5.3(A)) and true quantum chaos (sections 4.6.2, 5.2.1, 6), but rigorously excludes the possibility of unitary quantum computation, even in an ‘ideal’, noiseless system (sections 5-7). Any real computation is an in- ternally chaotic (multivalued) process of system complexity development occurring in different regimes at various complexity levels (sections 7.1-2). Unitary quantum machines, including their postulated ‘magic’, cannot be realised as such because their dynamically single-valued scheme is incom- patible with the irreducibly high dynamic randomness at quantum complex- ity levels (sections 4.5-7, 5.1, 5.2.2, 7.1-2) and should be replaced by the explicitly chaotic, intrinsically creative machines already realised in living organisms and providing their quite different, realistic kind of magic. The related concepts of reality-based, complex-dynamical nanotechnology, bio- technology and intelligence are outlined, together with the ensuing change in research strategy and content (sections 7.3, 8). The unreduced, dynami- cally multivalued solution of the quantum (and classical) many-body prob- lem reveals the true, complex-dynamical basis of solid-state dynamics, in- cluding the origin and internal dynamics of macroscopic quantum states (section 5.3(C)). -

A Statistical Mechanics View on Kitaev's Proposal for Quantum

A statistical mechanics view on Kitaev’s proposal for quantum memories R. Alicki†, M. Fannes‡ and M. Horodecki† † Institute of Theoretical Physics and Astrophysics University of Gda´nsk, Poland ‡ Instituut voor Theoretische Fysica K.U.Leuven, Belgium Abstract: We compute rigorously the ground and equilibrium states for Kitaev’s model in 2D, both the finite and infinite version, using an analogy with the 1D Ising ferromagnet. Next, we investigate the structure of the reduced dynamics in the presence of thermal baths in the Markovian regime. Special attention is paid to the dynamics of the topological freedoms which have been proposed for storing quantum information. 1 Introduction Despite the enormous activity in the field of quantum information in the last decade, the fundamental problem of how to protect quantum information for macroscopic periods of time remains open. In contrast to the popular belief the Fault Tolerant Quantum Computation (FTQC) ideas [1, 2, 3, 4, 5] do not provide the final solution to this problem. The mathematical mod- els behind these schemes are highly oversimplified, phenomenological, and arXiv:quant-ph/0702102v1 11 Feb 2007 do not take into account the restrictions imposed by the laws of thermo- dynamics. As FTQC involves time-dependent control by external fields the rigorous analysis of the corresponding models which can be derived from first principles is extremely difficult. In particular, the standard approximations based on the rigorous versions of Markovian limits (weak coupling or low density [6, 7, 8]), which yield descriptions consistent with thermodynamics, cannot be applied, see [9, 10, 11, 12, 13] in this context. -

The Structural and Dynamical Properties of Neutral-Ionic Phase Transitions

crystals Review Back to the Structural and Dynamical Properties of Neutral-Ionic Phase Transitions Marylise Buron-Le Cointe 1, Eric Collet 1 ID , Bertrand Toudic 1, Piotr Czarnecki 2 and Hervé Cailleau 1,* 1 Institut de Physique de Rennes, Université de Rennes 1-CNRS, UMR 6251, 263 Avenue du Général Leclerc, 35042 Rennes CEDEX, France; [email protected] (M.B.-L.C.); [email protected] (E.C.); [email protected] (B.T.) 2 Faculty of Physics, A. Mickiewicz University, ul.Umultowska 85, 61-614 Poznan, Poland; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +33-2-2323-6056 Academic Editors: Anna Painelli and Alberto Girlando Received: 1 August 2017; Accepted: 13 September 2017; Published: 23 September 2017 Abstract: Although the Neutral-Ionic transition in mixed stack charge-transfer crystals was discovered almost forty years ago, many features of this intriguing phase transition, as well as open questions, remain at the heart of today’s science. First of all, there is the most spectacular manifestation of electronic ferroelectricity, in connection with a high degree of covalency between alternating donor and acceptor molecules along stacks. In addition, a charge-transfer instability from a quasi-neutral to a quasi-ionic state takes place concomitantly with the stack dimerization, which breaks the inversion symmetry. Moreover, these systems exhibit exceptional one-dimensional fluctuations, with an enhancement of the effects of electron-lattice interaction. This may lead to original physical pictures for the dynamics of pre-transitional phenomena, as the possibility of a pronounced Peierls-type instability and/or the generation of unconventional non-linear excitations along stacks.