University of London Ma in Art History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

669 Other Artists

669 Other Artists Fig. 132. Francesco Fracanzano (attrib.) Rosa and Friends (drawing, Christie’s Images) Fig. 131. Giovan Battista Bonacina, Portrait of Salvator Rosa (engraving, 1662) Fig. 133. Francesco Fracanzano (attrib.), Rosa and Friends (drawing, British Museum, London) Fig. 134. Lorenzo Lippi, Orpheus (c. 1648, private collection, Florence) 670 Fig. 135. Lorenzo Lippi (and Rosa?), The Flight Fig. 136. Lorenzo Lippi, Allegory of Simulation into Egypt (1642, Sant’Agostino, Massa Marittima) (early 1640’s, Musèe des Beaux-Arts, Angers) Fig. 137. Baldassare Franceschini (“Il Volterrano”), Fig. 138. Baldassare Franceschini (“Il Volterrano”), A Sibyl (c. 1671?, Collezione Conte Gaddo della A Sibyl (c. 1671?, Collezione Conte Gaddo della Gherardesca, Florence) Gherardesca, Florence) 671 Fig. 140. Jacques Callot, Coviello (etching, Fig. 139. Jacques Callot, Pasquariello Trunno from the Balli di Sfessania series, early 1620’s) (etching, from the Balli di Sfessania series, early 1620’s) Fig. 142. Emblem of the Ant and Elephant (image from Hall, Illustrated Dictionary of Symbols in Eastern and Western Art, p. 8) Fig. 141. Coviello, from Francesco Bertelli, Carnavale Italiane Mascherato (1642); image from Nicoll, Masks Mimes and Miracles, p. 261) 672 Fig. 143. Jan Miel, The Charlatan (c. 1645, Hermitage, St. Petersburg) Fig. 144. Karel Dujardin, A Party of Charlatans in an Italian Landscape (1657, Louvre, Paris) Fig. 145. Cristofano Allori, Christ Saving Peter from Fig. 146. Cristofano Allori (finished by Zanobi the Waves (c. 1608-10, Collezione Bigongiari, Pistoia) Rosi after 1621), Christ Saving Peter from the Waves (Cappella Usimbardi, S. Trinità, Florence) 673 Fig. 148. Albrecht Dürer, St. Jerome in his Study (engraving, 1514) Fig. -

Touring a Unified Italy, Part 2 by John F

Browsing the Web: Touring A Unified Italy, Part 2 by John F. Dunn We left off last month on our tour of Italy—commemo- rating the 150th Anniversary of the Unification of the na- tion—with a relaxing stop on the island of Sardinia. This “Browsing the Web” was in- spired by the re- lease by Italy of two souvenir sheets to celebrate the Unifi- cation. Since then, on June 2, Italy released eight more souvenir sheets de- picting patriots of the Unification as well as a joint issue with San Marino (pictured here, the Italian issue) honoring Giuseppe and Anita Garibaldi, Anita being the Brazilian wife and comrade in arms of the Italian lead- er. The sheet also commemorates the 150th Anniversary of the granting of San Marino citizen- ship to Giuseppe Garibaldi. As we continue heading south, I reproduce again the map from Part 1 of this article. (Should you want Issue 7 - July 1, 2011 - StampNewsOnline.net 10 to refresh your memory, you can go to the Stamp News Online home page and select the Index by Subject in the upper right to access all previous Stamp News Online ar- ticles, including Unified Italy Part 1. So…moving right along (and still in the north), we next come to Parma, which also is one of the Italian States that issued its own pre-Unification era stamps. Modena Modena was founded in the 3rd century B.C. by the Celts and later, as part of the Roman Empire and became an important agricultural center. After the barbarian inva- sions, the town resumed its commercial activities and, in the 9th century, built its first circle of walls, which continued throughout the Middle Ages, until they were demolished in the 19th century. -

Academic Profiles of Conference Speakers

Academic Profiles of Conference Speakers 1. Cavazza, Marta, Associate Professor of the History of Science in the Facoltà di Scienze della Formazione (University of Bologna) Professor Cavazza’s research interests encompass seventeenth- and eighteenth-century Italian scientific institutions, in particular those based in Bologna, with special attention to their relations with the main European cultural centers of the age, namely the Royal Society of London and the Academy of Sciences in Paris. She also focuses on the presence of women in eighteenth- century Italian scientific institutions and the Enlightenment debate on gender, culture and society. Most of Cavazza’s published works on these topics center on Laura Bassi (1711-1778), the first woman university professor at Bologna, thanks in large part to the patronage of Benedict XIV. She is currently involved in the organization of the rich program of events for the celebration of the third centenary of Bassi’s birth. Select publications include: Settecento inquieto: Alle origini dell’Istituto delle Scienze (Bologna: Il Mulino, 1990); “The Institute of science of Bologna and The Royal Society in the Eighteenth century”, Notes and Records of The Royal Society, 56 (2002), 1, pp. 3- 25; “Una donna nella repubblica degli scienziati: Laura Bassi e i suoi colleghi,” in Scienza a due voci, (Firenze: Leo Olschki, 2006); “From Tournefort to Linnaeus: The Slow Conversion of the Institute of Sciences of Bologna,” in Linnaeus in Italy: The Spread of a Revolution in Science, (Science History Publications/USA, 2007); “Innovazione e compromesso. L'Istituto delle Scienze e il sistema accademico bolognese del Settecento,” in Bologna nell'età moderna, tomo II. -

![Downloads/Wp988j82g]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1919/downloads-wp988j82g-381919.webp)

Downloads/Wp988j82g]

[https://commons.warburg.sas.ac.uk/downloads/wp988j82g] Miglietti, Sara. The censor as reader : censorial responses to Bodin’s methodus in counter-Reformation Italy (1587-1607) / Sara Miglietti. 2016 Article To cite this version: Miglietti, S. (2016). The censor as reader : censorial responses to Bodin’s methodus in counter- Reformation Italy (1587-1607) / Sara Miglietti. History of European Ideas , 42(5), 707–721. https://doi.org/ https://doi.org/10.1080/01916599.2016.1153289 Available at: https://commons.warburg.sas.ac.uk/concern/journal_articles/d217qp48j DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/01916599.2016.1153289 Date submitted: 2019-07-22 Copyright is retained by the author. Terms and conditions for use of this material are defined in the User Deposit Agreement. The Censor as Reader: Censorial Responses to Bodin’s Methodus in Counter- Reformation Italy (1587-1607) SARA MIGLIETTI Department of German and Romance Languages and Literatures, Johns Hopkins University Gilman Hall 481 3400 N Charles Street Baltimore, MD 21218 (USA) Phone: +1-202-848-6032 Email: [email protected] 1 The Censor as Reader: Censorial Responses to Bodin’s Methodus in Counter- Reformation Italy (1587-1607) * SARA MIGLIETTI Department of German and Romance Languages and Literatures Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD Summary This essay investigates censorial responses to Jean Bodin’s Methodus (1566) in Counter-Reformation Italy, using evidence from Italian libraries and archives to shed new light on the process that led to the inclusion of the work in the Roman Expurgatory Index of 1607. By examining the diverse, and sometimes conflicting, opinions that Catholic censors expressed on Bodin’s text and the ‘errors’ it contained, the essay shows that even a relatively cohesive ‘reading community’ such as that of Counter-Reformation censors could nurture fundamental disagreement in evaluating the content and dangerousness of a book, as well as in devising appropriate countermeasures. -

The Papacy and the Birth of the Polish-Russian Hatred Autor Tekstu: Mariusz Agnosiewicz

The papacy and the birth of the Polish-Russian hatred Autor tekstu: Mariusz Agnosiewicz Tłumaczenie: Katarzyna Goliszek Niniejsze tłumaczenie fragmentu mojej publikacji, która jest częścią II tomu Kryminalnych dziejów papiestwa (http://www.racjonalista.pl/ks.php/k,2231), ukazało się wraz z komentarzem Czesława Białczyńskiego (http://pl.wikipedia.org/wiki/Czesław_Białczyński), pt. Reconciliation Poland — Russia, back in the years of 1610-1612 and the Counter-Reformation (http://bialczynski.wordpress.com/slowianie-tradycje-kultura- dzieje/zblizenie-polska-rosja/p apiestwo-i-narodziny-nienawisci -polsko-rosyjskiej-czyli-jeszcz e-o-latach-1610-1612-i-o-kontrr eformacji/reconciliation-poland -russia-back-in-the-years-of-16 10-1612-and-the-counter-reforma tion-eng/). MA For Anti memory of Piotr Skarga Pope Paul V (1605-1621), began his pontificate by pushing Poland for anti-Russian dymitriads, one of the most stupid and most tragic episodes of our history, and ended it when his circulatory system sustained a joyous overload during the procession in honor of the massacre of Czechs in the Thirty Years' War. The participation of the Papacy and the Jesuits in the tragic Polish anti-Russian rows is usually passed over in silence. For Russia's resurgent power it was a historically traumatic event that put a strain on the entire subsequent Polish-Russian relationships, and should never be ignored while remembrance of the partitions of Poland. When in 2005 Russia replaced their old national holiday commemorating the outbreak of the October Revolution with the Day of National Unity commemorating the liberation of Moscow from the Poles in Russia in 1612, the Vatican expressed concern that it could be of the anti-Catholic nature. -

121-Santa Maria in Publicolis.Pages

(121) Santa Maria in Publicolis The Church of Santa Maria in Publicolis, situated on Via in Publicolis at Piazza Costaguti in the rione of Sant'Eustachio, is the only Roman church dedicated to the Nativity of the blessed Virgin Mary. It is a little church built near the palace of the patrons, the Santacroce, who claimed to descend from Publio Valerio Publicola, a Roman consul who in 509 BC promulgated laws in favour of the lower classes. History: The church is mentioned in a papal bull promulgated in 1186 by Urban III. The consistory lawyer Andrea Santacroce had the church restored in 1465. Around 1640 the old church was in a state of disrepair, and it was pulled down. The cardinal Marcello Santacroce commissioned the architect Giovanni Antonio de' Rossi, who was the architect of the Santacroce family from c.1642-95, to design a new church. In 1835 Blessed Gaetano Errico instituted the Congregation of Missionaries of the Sacred Hearts of Jesus and Mary, and in 1858 he was given the church along with an adjacent building to house his congregation. Exterior: The façade is divided into three levels: the bottom two columns frame the entrance portal, above which is located a fresco surmounted by a broken pediment curved and four pilasters flank the two side niches. Inscription Deiparae Virgini in Publicolis MDCXLIII, or "the Virgin Mother of God in Publicolis 1643", separates the lower order from the central one, where there is a central window surmounted by a broken pediment. The third order presents a stained glass window surmounted by a curvilinear tympanum above which stands a cross. -

Unification of Italy 1792 to 1925 French Revolutionary Wars to Mussolini

UNIFICATION OF ITALY 1792 TO 1925 FRENCH REVOLUTIONARY WARS TO MUSSOLINI ERA SUMMARY – UNIFICATION OF ITALY Divided Italy—From the Age of Charlemagne to the 19th century, Italy was divided into northern, central and, southern kingdoms. Northern Italy was composed of independent duchies and city-states that were part of the Holy Roman Empire; the Papal States of central Italy were ruled by the Pope; and southern Italy had been ruled as an independent Kingdom since the Norman conquest of 1059. The language, culture, and government of each region developed independently so the idea of a united Italy did not gain popularity until the 19th century, after the Napoleonic Wars wreaked havoc on the traditional order. Italian Unification, also known as "Risorgimento", refers to the period between 1848 and 1870 during which all the kingdoms on the Italian Peninsula were united under a single ruler. The most well-known character associated with the unification of Italy is Garibaldi, an Italian hero who fought dozens of battles for Italy and overthrew the kingdom of Sicily with a small band of patriots, but this romantic story obscures a much more complicated history. The real masterminds of Italian unity were not revolutionaries, but a group of ministers from the kingdom of Sardinia who managed to bring about an Italian political union governed by ITALY BEFORE UNIFICATION, 1792 B.C. themselves. Military expeditions played an important role in the creation of a United Italy, but so did secret societies, bribery, back-room agreements, foreign alliances, and financial opportunism. Italy and the French Revolution—The real story of the Unification of Italy began with the French conquest of Italy during the French Revolutionary Wars. -

3 Architects, Antiquarians, and the Rise of the Image in Renaissance Guidebooks to Ancient Rome

Anna Bortolozzi 3 Architects, Antiquarians, and the Rise of the Image in Renaissance Guidebooks to Ancient Rome Rome fut tout le monde, & tout le monde est Rome1 Drawing in the past, drawing in the present: Two attitudes towards the study of Roman antiquity In the early 1530s, the Sienese architect Baldassare Peruzzi drew a section along the principal axis of the Pantheon on a sheet now preserved in the municipal library in Ferrara (Fig. 3.1).2 In the sixteenth century, the Pantheon was generally considered the most notable example of ancient architecture in Rome, and the drawing is among the finest of Peruzzi’s surviving architectural drawings after the antique. The section is shown in orthogonal projection, complemented by detailed mea- surements in Florentine braccia, subdivided into minuti, and by a number of expla- natory notes on the construction elements and building materials. By choosing this particular drawing convention, Peruzzi avoided the use of foreshortening and per- spective, allowing measurements to be taken from the drawing. Though no scale is indicated, the representation of the building and its main elements are perfectly to scale. Peruzzi’s analytical representation of the Pantheon served as the model for several later authors – Serlio’s illustrations of the section of the portico (Fig. 3.2)3 and the roof girders (Fig. 3.3) in his Il Terzo Libro (1540) were very probably derived from the Ferrara drawing.4 In an article from 1966, Howard Burns analysed Peruzzi’s drawing in detail, and suggested that the architect and antiquarian Pirro Ligorio took the sheet to Ferrara in 1569. -

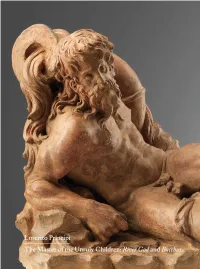

The Master of the Unruly Children: River God and Bacchus TRINITY

TRINITY FINE ART Lorenzo Principi The Master of the Unruly Children: River God and Bacchus London February 2020 Contents Acknowledgements: Giorgio Bacovich, Monica Bassanello, Jens Burk, Sara Cavatorti, Alessandro Cesati, Antonella Ciacci, 1. Florence 1523 Maichol Clemente, Francesco Colaucci, Lavinia Costanzo , p. 12 Claudia Cremonini, Alan Phipps Darr, Douglas DeFors , 2. Sandro di Lorenzo Luizetta Falyushina, Davide Gambino, Giancarlo Gentilini, and The Master of the Unruly Children Francesca Girelli, Cathryn Goodwin, Simone Guerriero, p. 20 Volker Krahn, Pavla Langer, Guido Linke, Stuart Lochhead, Mauro Magliani, Philippe Malgouyres, 3. Ligefiguren . From the Antique Judith Mann, Peta Motture, Stefano Musso, to the Master of the Unruly Children Omero Nardini, Maureen O’Brien, Chiara Padelletti, p. 41 Barbara Piovan, Cornelia Posch, Davide Ravaioli, 4. “ Bene formato et bene colorito ad imitatione di vero bronzo ”. Betsy J. Rosasco, Valentina Rossi, Oliva Rucellai, The function and the position of the statuettes of River God and Bacchus Katharina Siefert, Miriam Sz ó´cs, Ruth Taylor, Nicolas Tini Brunozzi, Alexandra Toscano, Riccardo Todesco, in the history of Italian Renaissance Kleinplastik Zsófia Vargyas, Laëtitia Villaume p. 48 5. The River God and the Bacchus in the history and criticism of 16 th century Italian Renaissance sculpture Catalogue edited by: p. 53 Dimitrios Zikos The Master of the Unruly Children: A list of the statuettes of River God and Bacchus Editorial coordination: p. 68 Ferdinando Corberi The Master of the Unruly Children: A Catalogue raisonné p. 76 Bibliography Carlo Orsi p. 84 THE MASTER OF THE UNRULY CHILDREN probably Sandro di Lorenzo di Smeraldo (Florence 1483 – c. 1554) River God terracotta, 26 x 33 x 21 cm PROVENANCE : heirs of the Zalum family, Florence (probably Villa Gamberaia) THE MASTER OF THE UNRULY CHILDREN probably Sandro di Lorenzo di Smeraldo (Florence 1483 – c. -

Leon Battista Alberti

THE HARVARD UNIVERSITY CENTER FOR ITALIAN RENAISSANCE STUDIES VILLA I TATTI Via di Vincigliata 26, 50135 Florence, Italy VOLUME 25 E-mail: [email protected] / Web: http://www.itatti.ita a a Tel: +39 055 603 251 / Fax: +39 055 603 383 AUTUMN 2005 From Joseph Connors: Letter from Florence From Katharine Park: he verve of every new Fellow who he last time I spent a full semester at walked into my office in September, I Tatti was in the spring of 2001. It T This year we have two T the abundant vendemmia, the large was as a Visiting Professor, and my Letters from Florence. number of families and children: all these husband Martin Brody and I spent a Director Joseph Connors was on were good omens. And indeed it has been splendid six months in the Villa Papiniana sabbatical for the second semester a year of extraordinary sparkle. The bonds composing a piano trio (in his case) and during which time Katharine Park, among Fellows were reinforced at the finishing up the research on a book on Zemurray Stone Radcliffe Professor outset by several trips, first to Orvieto, the medieval and Renaissance origins of of the History of Science and of the where we were guided by the great human dissection (in mine). Like so Studies of Women, Gender, and expert on the cathedral, Lucio Riccetti many who have worked at I Tatti, we Sexuality came to Florence from (VIT’91); and another to Milan, where were overwhelmed by the beauty of the Harvard as Acting Director. Matteo Ceriana guided us place, impressed by its through the exhibition on Fra scholarly resources, and Carnevale, which he had helped stimulated by the company to organize along with Keith and conversation. -

Women and Masks: the Economics of Painting and Meaning in the Mezza Figura Allegories by Lippi, Dandini and Martinelli

Originalveröffentlichung in: Fumagalli, Elena (Hrsg.): Firenze milleseicentoquaranta : arti, lettere, musica, scienza, Venezia 2010, 311-323 u. Abb. (Studi e ricerche / Kunsthistorisches Institut in Florenz, Max-Planck- Institut ; 6) ECKHARD LEUSCHNER WOMEN AND MASKS: THE ECONOMICS OF PAINTING AND MEANING IN THE MEZZA FIGURA ALLEGORIES BY LIPPI, DANDINI AND MARTINELLI A considerable number of paintings produced in Florence and usually dated to the late 1630s, the 1640s and early 1650s represents half-length figures of young women before a dark background. Among the attributes of these women, masks of similar shapes, probably made of leather and equipped with rather expressionless faces, appear regularly. Art history has not yet analysed these half-length figures as a group with related charac teristics, neither in terms of style and picture size nor in terms of allegori cal meaning. Most scholars, as a matter of fact, have limited themselves to discussing just one example, the socalled Simulazione by Lorenzo Lippi (fig. 1) in the museum of Angers which has acquired a certain prominence after having been chosen to decorate the cover of the Seicento exhibition in Paris in 1988.' In Lippi's painting, a woman with a serious expression on her face confronts the spectator with two objects in her hands, a mask and a pomegranate. Several art historians have interpreted one or both attributes as references to Simulatione in Cesare Ripa's Iconologia thus describing Lippi's woman as a personification of Simulation or of a simi lar allegorical quality, Dissimulation.1 Chiara d'Afflitto went one step fur 1 See Seicento, exhibition catalogue, Paris 1988; the entry for the picture by A. -

Gender Dynamics in Renaissance Florence Mary D

Early Modern Women: An Interdisciplinary Journal Vol. 11, No. 1 • Fall 2016 The Cloister and the Square: Gender Dynamics in Renaissance Florence Mary D. Garrard eminist scholars have effectively unmasked the misogynist messages of the Fstatues that occupy and patrol the main public square of Florence — most conspicuously, Benvenuto Cellini’s Perseus Slaying Medusa and Giovanni da Bologna’s Rape of a Sabine Woman (Figs. 1, 20). In groundbreaking essays on those statues, Yael Even and Margaret Carroll brought to light the absolutist patriarchal control that was expressed through images of sexual violence.1 The purpose of art, in this way of thinking, was to bolster power by demonstrating its effect. Discussing Cellini’s brutal representation of the decapitated Medusa, Even connected the artist’s gratuitous inclusion of the dismembered body with his psychosexual concerns, and the display of Medusa’s gory head with a terrifying female archetype that is now seen to be under masculine control. Indeed, Cellini’s need to restage the patriarchal execution might be said to express a subconscious response to threat from the female, which he met through psychological reversal, by converting the dangerous female chimera into a feminine victim.2 1 Yael Even, “The Loggia dei Lanzi: A Showcase of Female Subjugation,” and Margaret D. Carroll, “The Erotics of Absolutism: Rubens and the Mystification of Sexual Violence,” The Expanding Discourse: Feminism and Art History, ed. Norma Broude and Mary D. Garrard (New York: HarperCollins, 1992), 127–37, 139–59; and Geraldine A. Johnson, “Idol or Ideal? The Power and Potency of Female Public Sculpture,” Picturing Women in Renaissance and Baroque Italy, ed.