Exploring the Party Politicization of Animal Welfare in Multi-Level Electoral Systems: Analysis of Manifesto Discourse in UK Meso Elections 1998–2017

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

New Conference 2017.Indd

SCOTTISH GREENS AUTUMN CONFERENCE 2017 CONFERENCE LEADING THE CHANGE 21-22 October 2017 Contents 3. Welcome to Edinburgh 24. Sunday timetable 4. Welcome to Conference 26. Running order: Sunday 5. Guest speakers 28. Sunday events listings 6. How Conference works 32. Exhibitor information 10. Running order: Saturday 36. Venue maps 12. Child protection 40. Get involved! 13. Saturday events listings 41. Conference song 22. Saturday timetable 42. Exhibitor information Welcome to Edinburgh! I am pleased to be able to welcome you to the beautiful City of Edinburgh for the Scottish Green Party Autumn Conference. It’s been a challenging and busy year: firstly the very successful Local Council Elections, and then the snap General Election to test us even further. A big thank you to everyone involved. And congratulations – we have made record gains across the country electing more councillors than ever before! It is wonderful to see that Green Party policies have resonated with so many people across Scotland. We now have an opportunity to effect real change at a local level and make a tangible difference to people’s lives. At our annual conference we are able to further develop and shape our policies and debate the important questions that form our Green Party message. On behalf of the Edinburgh Greens, welcome to the Edinburgh Conference. Evelyn Weston, Co-convenor Edinburgh Greens 3 Welcome to our 2017 Autumn Conference! Welcome! We had a lot to celebrate at last year’s conference, with our best Holyrood election in more than a decade. This year we’ve gone even further, with the best council election in our party’s history. -

Talking 'Fracking': a Consultation on Unconventional Oil And

Talking "Fracking": A Consultation on Unconventional Oil and Gas Analysis of Responses October 2017 BUSINESS AND ENERGY social research Talking ‘Fracking’: A consultation on unconventional oil and gas. Analysis of responses Dawn Griesbach, Jennifer Waterton and Alison Platts Griesbach & Associates October 2017 Table of contents Executive Summary .................................................................................................. 1 1. Introduction and background ........................................................................... 4 Policy context 4 The Talking ‘Fracking’ consultation 4 About the analysis 5 2. About the respondents and responses ........................................................... 7 How responses were received 7 Number of responses included in the analysis 9 About the respondents (substantive responses only) 10 Responses to individual questions 11 3. Overview of responses ................................................................................... 13 Views on fracking and an unconventional oil and gas industry 13 Pattern of views across consultation questions 14 4. Social, community and health impacts (Q1) ................................................. 15 Health and wellbeing 16 Jobs and the local economy 17 Traffic, noise and light pollution 18 Housing and property 18 Quality of life and local amenity 18 Community resilience and cohesion 19 5. Community benefit schemes (Q2) .................................................................. 20 Criticisms of and reservations about community -

Green Parties and Elections to the European Parliament, 1979–2019 Green Par Elections

Chapter 1 Green Parties and Elections, 1979–2019 Green parties and elections to the European Parliament, 1979–2019 Wolfgang Rüdig Introduction The history of green parties in Europe is closely intertwined with the history of elections to the European Parliament. When the first direct elections to the European Parliament took place in June 1979, the development of green parties in Europe was still in its infancy. Only in Belgium and the UK had green parties been formed that took part in these elections; but ecological lists, which were the pre- decessors of green parties, competed in other countries. Despite not winning representation, the German Greens were particularly influ- enced by the 1979 European elections. Five years later, most partic- ipating countries had seen the formation of national green parties, and the first Green MEPs from Belgium and Germany were elected. Green parties have been represented continuously in the European Parliament since 1984. Subsequent years saw Greens from many other countries joining their Belgian and German colleagues in the Euro- pean Parliament. European elections continued to be important for party formation in new EU member countries. In the 1980s it was the South European countries (Greece, Portugal and Spain), following 4 GREENS FOR A BETTER EUROPE their successful transition to democracies, that became members. Green parties did not have a strong role in their national party systems, and European elections became an important focus for party develop- ment. In the 1990s it was the turn of Austria, Finland and Sweden to join; green parties were already well established in all three nations and provided ongoing support for Greens in the European Parliament. -

1. Debbie Abrahams, Labour Party, United Kingdom 2

1. Debbie Abrahams, Labour Party, United Kingdom 2. Malik Ben Achour, PS, Belgium 3. Tina Acketoft, Liberal Party, Sweden 4. Senator Fatima Ahallouch, PS, Belgium 5. Lord Nazir Ahmed, Non-affiliated, United Kingdom 6. Senator Alberto Airola, M5S, Italy 7. Hussein al-Taee, Social Democratic Party, Finland 8. Éric Alauzet, La République en Marche, France 9. Patricia Blanquer Alcaraz, Socialist Party, Spain 10. Lord John Alderdice, Liberal Democrats, United Kingdom 11. Felipe Jesús Sicilia Alférez, Socialist Party, Spain 12. Senator Alessandro Alfieri, PD, Italy 13. François Alfonsi, Greens/EFA, European Parliament (France) 14. Amira Mohamed Ali, Chairperson of the Parliamentary Group, Die Linke, Germany 15. Rushanara Ali, Labour Party, United Kingdom 16. Tahir Ali, Labour Party, United Kingdom 17. Mahir Alkaya, Spokesperson for Foreign Trade and Development Cooperation, Socialist Party, the Netherlands 18. Senator Josefina Bueno Alonso, Socialist Party, Spain 19. Lord David Alton of Liverpool, Crossbench, United Kingdom 20. Patxi López Álvarez, Socialist Party, Spain 21. Nacho Sánchez Amor, S&D, European Parliament (Spain) 22. Luise Amtsberg, Green Party, Germany 23. Senator Bert Anciaux, sp.a, Belgium 24. Rt Hon Michael Ancram, the Marquess of Lothian, Former Chairman of the Conservative Party, Conservative Party, United Kingdom 25. Karin Andersen, Socialist Left Party, Norway 26. Kirsten Normann Andersen, Socialist People’s Party (SF), Denmark 27. Theresa Berg Andersen, Socialist People’s Party (SF), Denmark 28. Rasmus Andresen, Greens/EFA, European Parliament (Germany) 29. Lord David Anderson of Ipswich QC, Crossbench, United Kingdom 30. Barry Andrews, Renew Europe, European Parliament (Ireland) 31. Chris Andrews, Sinn Féin, Ireland 32. Eric Andrieu, S&D, European Parliament (France) 33. -

Recruited by Referendum: Party Membership in the SNP and Scottish Greens

Recruited by Referendum: Party membership in the SNP and Scottish Greens Lynn Bennie, University of Aberdeen ([email protected]) James Mitchell, University of Edinburgh ([email protected]) Rob Johns, University of Essex ([email protected]) Work in progress – please do not cite Paper prepared for the 66th Annual International Conference of the Political Science Association, Brighton, UK, 21-23 March 2016 1 Introduction This paper has a number of objectives. First, it documents the dramatic rise in membership of the Scottish National Party (SNP) and Scottish Green Party (SGP) following the 2014 referendum on Scottish independence. The pace and scale of these developments is exceptional in the context of international trends in party membership. Secondly, the paper examines possible explanations for these events, including the movement dynamics of pre and post referendum politics. In doing so, the paper outlines the objectives of a new ESRC- funded study of the SNP and Scottish Greens, exploring the changing nature of membership in these parties following the referendum.1 A key part of the study will be a survey of SNP and SGP members in the spring of 2016 and we are keen to hear views of academic colleagues on questionnaire design, especially those working on studies of other parties’ members. The paper concludes by considering some of the implications of the membership surges for the parties and their internal organisations. The decline of party membership Party membership across much of the Western world has been in decline for decades (Dalton 2004, 2014; Whiteley 2011; van Biezen et al. -

Wales Green Party

Wales Green Party 1 CONTENTS Introduction – Anthony Slaughter 2 Our candidates 4 Green Guarantee: Our top 10 points 6 Our Approach 9 Joined-up thinking and policies Listening to science and honesty with the public Responding at scale Leading change that is fair Listening and learning government A Wales that can really work for change Finding the finance Green Window on the Valleys 12 How it fits together 14 Green Window on Rural and Coastal areas 16 Our Plan of Action 18 ENVIRONMENT 19 COMMUNITY 22 WORK 25 GOVERNMENT 28 Green Window on our Cities and Urban areas 32 2 1 his election is taking place in challenging These ambitious plans include the establishment times. The ongoing Covid 19 crisis has of a Green Transformation Fund for Wales which exposed the serious structural and systemic will raise finance, through issuing bonds, to fund: faults in our society and highlighted the ■ building thousands of zero carbon new homes obscene and growing levels of inequality each year thatT are destroying our communities. The coming INTRODUCTION severe financial recession will be made all the worse ■ installing rooftop solar on every hospital here in Wales by the predictable negative impacts of ■ converting thousands of houses to warm zero the Brexit fallout. This will impact most heavily on carbon homes each year poorer communities leaving them even more vulnerable. ■ replacing all diesel buses in Wales with electric Meanwhile both the ever-present Climate Emergency buses assembled in Wales and Nature Crisis become more urgent. Previous ‘once Wales Green Party’s Green New Deal will transform in a lifetime’ extreme weather events are happening Welsh society, providing Green jobs in a genuine with increasing regularity across the globe. -

Partisan Dealignment and the Rise of the Minor Party at the 2015 General Election

MEDIA@LSE MSc Dissertation Series Compiled by Bart Cammaerts, Nick Anstead and Richard Stupart “The centre must hold” Partisan dealignment and the rise of the minor party at the 2015 general election Peter Carrol MSc in Politics and Communication Other dissertations of the series are available online here: http://www.lse.ac.uk/media@lse/research/mediaWorkingPapers/Electroni cMScDissertationSeries.aspx MSc Dissertation of Peter Carrol Dissertation submitted to the Department of Media and Communications, London School of Economics and Political Science, August 2016, in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the MSc in Politics and Communication. Supervised by Professor Nick Couldry. The author can be contacted at: [email protected] Published by Media@LSE, London School of Economics and Political Science ("LSE"), Houghton Street, London WC2A 2AE. The LSE is a School of the University of London. It is a Charity and is incorporated in England as a company limited by guarantee under the Companies Act (Reg number 70527). Copyright, Peter Carrol © 2017. The authors have asserted their moral rights. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means without the prior permission in writing of the publisher nor be issued to the public or circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published. In the interests of providing a free flow of debate, views expressed in this dissertation are not necessarily those of the compilers or the LSE. 2 MSc Dissertation of Peter Carrol “The centre must hold” Partisan dealignment and the rise of the minor party at the 2015 general election Peter Carrol ABSTRACT For much of Britain’s post-war history, Labour or the Conservatives have formed a majority government, even when winning less than half of the popular vote. -

European Manifesto 2004

EUROPEAN ELECTION MANIFESTO 2004 From our MEPs Real Progress: The future is Green A Message from Jean Lambert A Message from Caroline Lucas This manifesto puts forward a distinctive radical message that is based Contents Green MEP for London Green MEP for South East England on our core principles of ecological sustainability and economic justice. The EU needs the Greens. Hard-won gains Being elected as one of Britain’s first Green From our MEPs Inside front cover such as the commitment to sustainable MEPs has been a wonderful opportunity to In 1999, the British people elected two Green Party history. We want a social Europe, one that protects The future is Green 1 members of the European Parliament. In 2000, London workers, public services and minorities. We want a development and conflict prevention are at raise the profile of the Green Party and green returned three Green members of the London Assembly. commonsense Europe, one that works for the interests of Protecting our environment 2 risk if the Greens aren’t there to push policy politics in the UK and, working with In 2003, Scotland returned seven Green members of the all. An economy for people and planet 6 in that direction. It was teamwork between colleagues, to act as a catalyst for vitally Scottish Parliament. Greens in other countries have Some decisions are best made at a European level. We Safe food and sustainable farming 10 Green MEPs and environment ministers that needed change within the EU – for peace, ministers of state and members of national applaud the environmental, judicial and safety Transport 14 kept the Kyoto Protocol alive. -

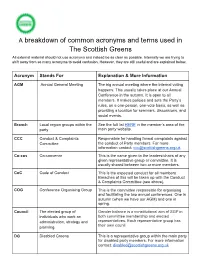

A Breakdown of Common Acronyms and Terms Used in the Scottish

A breakdown of common acronyms and terms used in The Scottish Greens All external material should not use acronyms and instead be as clear as possible. Internally we are trying to shift away from so many acronyms to avoid confusion. However, they are still useful and are explained below. Acronym Stands For Explanation & More Information AGM Annual General Meeting The big annual meeting where the internal voting happens. This usually takes place at our Annual Conference in the autumn. It is open to all members. It makes policies and sets the Party’s rules, on a one-person, one-vote basis, as well as providing a location for seminars, discussions, and social events. Branch Local region groups within the See the full list HERE in the member’s area of the party main party website. CCC Conduct & Complaints Responsible for handling formal complaints against Committee the conduct of Party members. For more information contact: [email protected] Co-cos Co-convenor This is the name given to the leaders/chairs of any given representative group or committee. It is usually shared between two or more members. CoC Code of Conduct This is the expected conduct for all members. Breaches of this will be taken up with the Conduct & Complaints Committee (see above). COG Conference Organising Group This is the committee responsible for organising and facilitating the two annual conferences. One in autumn (when we have our AGM) and one in spring. Council The elected group of Gender balance is a constitutional aim of SGP in individuals who work on both committee membership and elected administration, strategy and representatives. -

Greens Oppose Environment of Catholic Schools in Scotland

Fr Colin ACN reacts to Pro-life activists MacInnes unanimous ISIS stand up in reports from genocide Edinburgh and quake in recognition by Glasgow. Ecuador. Page 7 MPs. Page 3 Pages 4-5 No 5669 VISIT YOUR NATIONAL CATHOLIC NEWSPAPER ONLINE AT WWW.SCONEWS.CO.UK Friday April 29 2016 | £1 Greens oppose environment of Catholic schools in Scotland I Controversial stance omitted from 2016 Scottish Green Party manifesto but still remains party policy By Ian Dunn and Daniel Harkins what the thinking behind that policy is. last year, the group said that ‘our posi- Catholic education in Scotland out of education in Scotland. It doesn’t seem to be about tolerating tion stated in [a] 2013 report has not their manifesto for the 2016 elections. “I am very supportive of state-funded THE Scottish Green Party has other people’s wishes, or allowing changed from the belief that sectarian- Mr McGrath suggested the hostile Catholic schools,” Ms Sturgeon told the admitted that it remains intent on parental choices, but instead imposing ism would not be eradicated by closing response the party received in 2007 to SCO last year. “They perform ending state-funded Catholic edu- a one size fits all system contrary to all schools.’ its education policy may have moti- very well.” cation in Scotland. developments in education all over Another Green candidate, David vated members to leave it out of their Ms Davidson has also told the SCO Despite the policy being left out of the world.” Officer, who is on the Scottish Green manifesto this time. -

A City-Level Analysis of B2C Carsharing in Europe

A city-level analysis of B2C carsharing in Europe Master’s thesis Jan Lodewijk Blomme Master’s program: Innovation Sciences Student number: 3642658 Email: [email protected] Telephone: +316 4419 6103 Supervisor: Prof. Dr. Koen Frenken Second reader: Dr. Wouter Boon Date: May 13, 2016 A city-level analysis of B2C carsharing in Europe – Master’s thesis J. L. Blomme Summary Business to consumer (B2C) carsharing is a phenomenon that started in Europe in the 1940s but has gained in popularity quickly since the 1990s. This development is a welcome addition to the means that can be supported by local governments in order to mitigate greenhouse gas emissions and curb congestion in cities. Cities have however experienced differences in the extent to which carsharing has been adopted in their area. This research uncovers several important city features that explain this differential adoption of carsharing in a city. This study uses the multi-level perspective (MLP) to distinguish between the contemporary car regime and the carsharing niche. Several indicators are identified that theoretically would weaken the regime and/or strengthen the niche in a city. These indicators are therefore expected to have a noticeable effect on the amount of shared B2C vehicles in cities, as the local car regime would be weaker. The research develops a unique database by collecting the amount of shared B2C cars online through carsharing operator (CSO) websites. Independent variables are in turn collected through various sources both on- and offline, including national statistics databases and Eurostat. Results are initially analyzed through bivariate correlations. -

Les Thèses Récentes Soutenues En Histoire Contemporaine (Février 2018)

Les thèses récentes soutenues en histoire contemporaine (février 2018) Nous recensons ici un ensemble de thèses d’histoire contemporaine soutenues en 2017 (et de rares thèses plus anciennes qui nous avaient précédemment échappé) avec, lorsque nous avons pu trouver ces informations en ligne, nom, titre, université et date de soutenance, composition du jury et résumé de la thèse. La discipline de la thèse peut ne pas être l’histoire, tant que le sujet nous a semblé relever de l’histoire contemporaine. Ce recensement ne peut pas être complet, même si nous avons fait de notre mieux… Pour signaler une thèse soutenue après août 2017 et non recensée ici (elle sera annoncée dans la prochaine livraison) : - vérifiez d’abord qu'elle n'avait pas été annoncée en juillet 2017 : http://ahcesr.hypotheses.org/765 - remplissez ce formulaire : https://ahcesr.hypotheses.org/nous-signaler-une-soutenance-de-these - ou bien écrivez-nous : [email protected] Julie d’Andurain Stéphane Lembré Claire Lemercier Manuela Martini Nicolas Patin Clément Thibaud 1 Index des thèses ALIX, Sébastien-Akira, L’éducation progressiste aux Etats-Unis : histoire, philosophie et pratiques (1876-1919), thèse soutenue le 15 octobre 2016, à l’université Paris-Descartes. ARMAND, Cécile, « Placing the history of advertising » : une histoire spatiale de la publicité à Shanghai (1905-1949), thèse soutenue le 27 juin 2017 à l’ENS de Lyon. AUBÉ, Carole, La naissance du Sentier. L’espace du commerce des tissus dans la première moitié du XIXe siècle, thèse soutenue le 14 décembre 2017, à l’EHESS. AYACHE, Nadia, Maillage et implantation du Socialisme en Aquitaine (acteurs, réseaux, mobilisations électorales) de 1958 à la fin des années 1990, thèse soutenue le 7 novembre 2017, à l’université Bordeaux Montaigne.