Dwain Chambers Runs out of Time CHARLISH, P

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Olympic, World, European and Commonwealth Champion, Greg

Olympic, World, European and Commonwealth champion, Greg Rutherford is Great Britain’s most decorated long jumper and one of the country’s most successful Olympic athletes. After a successful junior career, Greg won gold at the London 2012 Olympics - changing his life forever and playing his part in the most successful night of British olympic sport in history. This iconic victory began a winning streak of gold medals; at the 2014 European Championships, 2014 Commonwealth Games and the 2015 World Championships. In 2015, Greg topped the long jump ranking in the IAAF Diamond League, the athletics equivalent of the Champions League. At the end of his 2015 season, he held every available elite outdoor title. In 2016 at the Rio Olympic’s, Greg backed up his 2012 Olympic success with a further Olympic medal - he also found himself on the Strictly Come Dancing ballroom floor shortly after! Greg is the British record holder, both indoors and outdoors, with bests of 8.26m (indoors) and 8.51m (outdoors). These sporting successes place Greg among the ranks of the British supreme athletics performers - simultaneously holding 4 major outdoors titles - he sits alongside legends such as, Linford Christie, Sally Gunnell, Johnathan Edwards & Daley Thompson. Greg’s route to the top was anything but smooth. From humble and often difficult beginnings, Greg rebelled during his teenage years and ended up dropping out of school, telling his teachers he was going to be a professional sportsman, no matter what - despite having no job, no money and little more than a firm belief in his own raw talent. -

Welcome WHAT IS IT ABOUT GOLF? EX-GREENKEEPERS JOIN

EX-GREENKEEPERS JOIN HEADLAND James Watson and Steve Crosdale, both former side of the business, as well as the practical. greenkeepers with a total of 24 years experience in "This position provides the ideal opportunity to the industry behind them, join Headland Amenity concentrate on this area and help customers as Regional Technical Managers. achieve the best possible results from a technical Welcome James has responsibility for South East England, perspective," he said. including South London, Surrey, Sussex and Kent, James, whose father retired as a Course while Steve Crosdale takes East Anglia and North Manager in December, and who practised the London including Essex, profession himself for 14 years before moving into WHAT IS IT Hertfordshire and sales a year ago, says that he needed a new ABOUT GOLF? Cambridgeshire. challenge but wanted something where he could As I write the BBC are running a series of Andy Russell, use his experience built programmes in conjunction with the 50th Headland's Sales and up on golf courses anniversary of their Sports Personality of the Year Marketing Director said around Europe. Award with a view to identifying who is the Best of that the creation of these "This way I could the Best. two new posts is take a leap of faith but I Most sports are represented. Football by Bobby indicative of the way the didn't have to leap too Moore, Paul Gascoigne, Michael Owen and David company is growing. Beckham. Not, surprisingly, by George Best, who was James Watson far," he explains. "I'm beaten into second place by Princess Anne one year. -

Anewplace Toplay

U-14 girls Carole Hester’s ON THE MARKET win Roseville Looking About Guide to local real estate Tournament UDJ column .......................................Inside ..........Page A-8 .............Page A-3 INSIDE Mendocino County’s World briefly The Ukiah local newspaper .......Page A-2 Tomorrow: Sunny; near-record heat 7 58551 69301 0 FRIDAY June 23, 2006 50 cents tax included DAILY JOURNAL ukiahdailyjournal.com 44 pages, Volume 148 Number 75 email: [email protected] Discussion on ordinance turns testy By KATIE MINTZ whose terms coincide with those of the The Daily Journal UKIAH CITY COUNCIL councilmembers who appointed them. The Ukiah City Council covered a If passed, the ordinance will allow number of topics Wednesday evening at each councilmember to nominate a its regular meeting, some with a tinge of to the City Planning Commission. planning commissioner, but will also testy discussion. Currently, the city has five planning require the council as a whole to ratify Of the most fervent was the council’s commissioners -- Ken Anderson, Kevin the selection by a full vote at a City deliberation regarding the introduction Jennings, James Mulheren, Judy Pruden Council meeting. of an ordinance that would affect how and Michael Whetzel -- who were each planning commissioners are appointed appointed by a council member, and See COUNCIL, Page A-10 ANEW PLACE TO PLAY Ukiah soldier killed in Iraq Orchard Park to open on Saturday The Daily Journal Sgt. Jason Buzzard, 31, of Ukiah, has been reported killed in Iraq. The Department of Defense has not yet made a public announcement although a family member has confirmed his death. -

I Vincitori I Campionati Europei Indoor

0685-0862_CAP08a_Manifestazioni Internazionali_1 - 2009 11/07/16 11:41 Pagina 824 ANNUARIO 2016 I campionati Europei indoor Le sedi GIOCHI EUROPEI 6. 1975 Katowice (pol) 16. 1985 Atene (gre) 26. 2000 Gand (bel) 1. 1966 Dortmund (frg) 8/9 marzo, Rondo, 160m 2/3 marzo, 25/27 febbraio, 27 marzo, Westfallenhalle, 160m 7. 1976 Monaco B. (frg) Peace and Friendship Stadium, 200m Flanders Indoor Hall, 200m 2. 1967 Praga (tch) 21/22 febbraio, Olympiahalle, 179m 17. 1986 Madrid (spa) 27. 2002 Vienna (aut) 11/12 marzo, Sportovní Hala Pkojf, 160m 8. 1977 San Sebastian (spa) 22/23 febbraio, Palacio de los Deportes, 164m 1/3 marzo, Ferry-Dusika-Halle, 200m 3. 1968 Madrid (spa) 12/13 marzo, Anoeta, 200m 18. 1987 Liévin (fra) 28. 2005 Madrid (spa) 9/10 marzo, 9. 1978 Milano (ita) 21/22 febbraio, Palais des Sports, 200m 4/6 marzo, Palacio de los Deportes, 200m 19. 1988 (ung) Palacio de los Deportes, 182m 11/12 marzo, Palazzo dello Sport, 200m Budapest 29. 2007 Birmingham (gbr) 5/6 marzo, Sportscárnok, 200m 4. 1969 Belgrado (jug) 10. 1979 Vienna (aut) 2/4 marzo, National Indoor Arena, 200m 20. 1989 (ola) 8/9 marzo, Veletrzna hala, 195m 24/25 febbraio, Den Haag 30. 2009 (ita) 17/18 febbraio, Houtrust, 200m Torino Ferry-Dusika-Halle, 200m 6/8 marzo, Oval, 200 m 21. 1990 Glasgow (gbr) CAMPIONATI EUROPEI 11. 1980 Sindelfingen (frg) 3/4 marzo, Kelvin Hall, 200m 31. 2011 Parigi-Bercy (fra) 1. 1970 (aut) 1/2 marzo, Glaspalast, 200m Vienna 22. 1992 Genova (ita) 4/6 marzo, 12. -

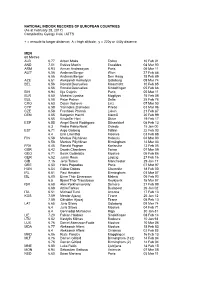

As at February 28, 2017) Compiled by György Csiki / ATFS

NATIONAL INDOOR RECORDS OF EUROPEAN COUNTRIES (As at February 28, 2017) Compiled by György Csiki / ATFS + = enroute to longer distance; A = high altitude; y = 220y or 440y distance MEN 60 Metres ALB 6.77 Arben Maka Torino 10 Feb 01 AND 7.01 Estéve Martin Escaldes 04 Mar 00 ARM 6.93 Arman Andreasyan Paris 05 Mar 11 AUT* 6.56 Andreas Berger Wien 27 Feb 88 6.56 Andreas Berger Den Haag 18 Feb 89 AZE 6.61 Aleksandr Kornelyuk Göteborg 09 Mar 74 BEL 6.56 Ronald Desruelles Maastricht 10 Feb 85 6.56 Ronald Desruelles Sindelfingen 05 Feb 88 BIH 6.94 Ilija Cvijetic Paris 05 Mar 11 BLR 6.60 Maksim Lynsha Mogilyov 15 Feb 08 BUL 6.58 Petar Petrov Sofia 25 Feb 78 CRO 6.63 Dejan Vojnovic Linz 07 Mar 03 CYP 6.58 Yiannakis Zisimides Pireás 03 Mar 96 CZE 6.58 Frantisek Ptácník Liévin 21 Feb 87 DEN 6.65 Benjamin Hecht Malmö 20 Feb 99 6.65 Kristoffer Hari Skive 19 Feb 17 ESP 6.55 Angel David Rodriguez Düsseldorf 08 Feb 13 6.3 Pedro Pablo Nolet Oviedo 15 Jan 00 EST 6.71 Argo Golberg Tallinn 22 Feb 03 6.4 Enn Lilienthal Moskva 03 Feb 88 FIN 6.58 Markus Pöyhönen Helsinki 04 Mar 03 6.58 Markus Pöyhönen Birmingham 14 Mar 03 FRA 6.45 Ronald Pognon Karlsruhe 13 Feb 05 GBR 6.42 Dwain Chambers Torino 07 Mar 09 GEO 6.71 Besik Gotsiridze Moskva 05 Feb 86 GER 6.52 Julian Reus Leipzig 27 Feb 16 GIB 7.16 Jerai Torres Manchester 29 Jan 17 GRE 6.50 Haris Papadiás Paris 07 Mar 97 HUN 6.54 Gábor Dobos Chemnitz 18 Feb 00 IRL 6.61 Paul Hession Birmingham 03 Mar 07 ISL 6.80 Einar Thór Einarsson Malmö 06 Feb 93 6.5 Bjarni Thór Traustason Reykjavík 15 Mar 97 ISR 6.68 Alex Porkhomovskiy -

A Small Sample of Some Athlete and Celebrity Users on Prohero.Com

A small sample of some athlete and celebrity users on ProHero.com: Norman Nixon https://prohero.com/profile/normnixon – FOX Sports Analyst and former Los Angeles Laker Point Guard. Won two NBA championships and was twice named an NBA All-Star. Spent 12 seasons with the Lakers. During his NBA career, he scored 12,065 points (15.7 points per game) and had 6,386 assists (8.3) in 768 games played. As a professional sports agent he represented, Doug Edwards, Samaki Walker, Jalen Rose, Maurice Taylor, Teddy Dupay, Gary Grant, Gerald Fitch, the NFL's Peter Warrick, Larry Smith, and Al Wilson, and entertainers such as LL Cool J and TLC. Maurice Greene https://prohero.com/profile/Mogreene World Record Holder, Olympian. The world’s fastest man. 2x 2000 Olympic champion in the 100m and 4x100 m relay. Former 100m world record holder with a time of 9.79 sec. Still 60m World Record holder with a time of 6.39 sec. Mike Little – https://prohero.com/profile/mikelittle Co-founder and developer of WordPress. Used by approx. 25% of the world’s websites accounting for the top ten of all website traffic. Amanda Bingson – https://prohero.com/profile/bingson Olympian and American record holder in the hammer throw and multiple medalist. Graced the 2016 cover of ESPN’s body issue. American Track and Field athlete training for the upcoming Olympic Games. Blaine Bishop – https://prohero.com/profile/Bbishop23 NFL great. Blaine was drafted in the eighth round (214 overall) of the 1993 NFL Draft by the Houston Oilers. -

2012 European Championships Statistics – Men's 100M

2012 European Championships Statistics – Men’s 100m by K Ken Nakamura All time performance list at the European Championships Performance Performer Time Wind Name Nat Pos Venue Year 1 1 9.99 1.3 Francis Obikwelu POR 1 Göteborg 20 06 2 2 10.04 0.3 Darren Campbell GBR 1 Budapest 1998 3 10.06 -0.3 Francis Obikwelu 1 München 2002 3 3 10.06 -1.2 Christophe Lemaitre FRA 1sf1 Barcelona 2010 5 4 10.08 0.7 Linford Christie GBR 1qf1 Helsinki 1994 6 10.09 0.3 Linford Christie 1sf1 Sp lit 1990 7 5 10.10 0.3 Dwain Chambers GBR 2 Budapest 1998 7 5 10.10 1.3 Andrey Yepishin RUS 2 Göteborg 2006 7 10.10 -0.1 Dwain Chambers 1sf2 Barcelona 2010 10 10.11 0.5 Darren Campbell 1sf2 Budapest 1998 10 10.11 -1.0 Christophe Lemaitre 1 Barce lona 2010 12 10.12 0.1 Francis Obikwelu 1sf2 München 2002 12 10.12 1.5 Andrey Yepishin 1sf1 Göteborg 2006 14 10.14 -0.5 Linford Christie 1 Helsinki 1994 14 7 10.14 1.5 Ronald Pognon FRA 2sf1 Göteborg 2006 14 7 10.14 1.3 Matic Osovnikar SLO 3 Gö teborg 2006 17 10.15 -0.1 Linford Christie 1 Stuttgart 1986 17 10.15 0.3 Dwain Chambers 1sf1 Budapest 1998 17 10.15 -0.3 Darren Campbell 2 München 2002 20 9 10.16 1.5 Steffen Bringmann GDR 1sf1 Stuttgart 1986 20 10.16 1.3 Ronald Pognon 4 Göteb org 2006 20 9 10.16 1.3 Mark Lewis -Francis GBR 5 Göteborg 2006 20 9 10.16 -0.1 Jaysuma Saidy Ndure NOR 2sf2 Barcelona 2010 24 12 10.17 0.3 Haralabos Papadias GRE 3 Budapest 1998 24 12 10.17 -1.2 Emanuele Di Gregorio IA 2sf1 Barcelona 2010 26 14 10.18 1.5 Bruno Marie -Rose FRA 2sf1 Stuttgart 1986 26 10.18 -1.0 Mark Lewis Francis 2 Barcelona 2010 -

Linford Christie

LINFORD CHRISTIE Europe’s greatest ever 100m sprinter Undoubtedly Europe’s greatest ever 100m sprinter, Linford Christie became the Olympic 100m Champion after winning the Gold Medal in Barcelona, 1992. In an International career spanning seventeen years, Linford competed over 60 times for his country and won more major championship medals, 23, than any other British sprinter. Linford is the only British athlete to have won Gold medals in the 100 metres at all four major competitions and was the first European to have run sub ten seconds. His fastest time 9.87 seconds, recorded when he won the 1993 World Championship in Stuttgart, is the European record. Topics Amongst the numerous awards bestowed upon Linford was the prestigious 1993 Motivation ‘BBC Sports Personality of the Year’ and ‘European Athlete of the Year’. Olympics He has worked as a technical commentator in Athletics and has presented many Sports sports specific programmes over the years. Linford was CNN’s lead commentator throughout the Olympic Games Period when he analysed the athletics and provided his expert views having been in the sport for over 30 years. He is also one of Britain’s most successful Coaches and had 5 Athletes competing in the London Olympics. Linford launched Street Athletics in June 2004 in conjunction with Manchester City Council, in an attempt to find the raw sprinting talent that is being lost to other sports and computer games. The scheme was extended to cover 4 cities in 2006. Since 2005 the project has grown and become more successful, visiting its greatest amount of venues, 22, in 2009 and still going strong in 2014. -

“Where the World's Best Athletes Compete”

6 0 T H A N N U A L “Where the world’s best athletes compete” MEDIA INFORMATION updated on April 5, 2018 6 0 T H A N N U A L “Where the world’s best athletes compete” MEDIA INFORMATION April 5, 2018 Dear Colleagues: The 60th Annual Mt. SAC Relays is set for April 19, 20 and 21, 2018 at Murdock Stadium, on the campus of El Camino College in Torrance, CA. Once again we expect over 5,000 high school, masters, community college, university and other champions from across the globe to participate. We look forward to your attendance. Due to security reasons, ALL MEDIA CREDENTIALS and Parking Permits will be held at the Credential Pick-up area in Parking Lot D, located off of Manhattan Beach Blvd. (please see attached map). Media Credentials and Parking Permit will be available for pick up on: Thursday, April 19 from 2pm - 8pm Friday, April 20 from 8am - 8pm Saturday, April 21 from 8am - 2pm Please present a photo ID to pick up your credentials and then park in lot C which is adjacent to the media credential pick up. Please remember to place your parking pass in your window prior to entering the stadium. The Mt. SAC Relays provides the following services for members of the media: Access to press box, infield and media interview area Access to copies of official results as they become available Complimentary food and beverage for all working media April 20 & 21 WiFi access Additional information including time schedules, dates, times and other important information can be accessed via our website at http://www.mtsacrelays.com If you have any additional questions or concerns, please feel free to call or e-mail me at anytime. -

QUIZ TIME Test Your Knowledge of All Things Olympic

TASK TIME ONLINE - PART 8 QUIZ TIME Test your knowledge of all things Olympic. Use the information from Part 8 in the newspaper to see how much you understand. 1. What is the name of the medal given to a sportsperson who demonstrates an outstanding level of sportsmanship? 2. Which country did Lawrence Lemieux represent at the 1988 Olympics? In which sport? 3. What are the ‘medals of friendship’ made up of? 4. What is the connection between the 2012 London Olympics and women? 5. What is the name given to a judo competitor? 6. Where would you be if you were standing in the Whispering Gallery? 7. Who was Australia’s first winner on the athletics track? 8. In which event did Australian Mitchell watt compete at London 2012? 9. Name two sports at these Olympics in which athletes compete in weight categories. Can you think of another sport? 10. How long does a women’s boxing bout last if it goes the full round? COMPETITION CATEGORY Judo Weight Categories In Judo, there are seven weight categories for men and seven for women but the list has been muddled. Can you put the list together so it is in order with the correct weights for each category? In which category would you fight? Men Category Weight Half Middleweight over 100 Kg Half Lightweight over 60 up to and including 66 Kg Lightweight over 81 up to and including 90 Kg Half Heavyweight up to and including 60 Kg Extra Lightweight over 90 up to and including 100 Kg Heavyweight over 73 up to and including 81 Kg Middleweight over 66 up to and including 73 Kg Women Category Weight Lightweight over 78 Kg Middleweight over 52 up to and including 57 Kg Heavyweight over 57 up to and including 63 Kg Half Lightweight over 63 up to and including 70 Kg Half Heavyweight over 70kg up to and including 78 Kg Extra Lightweight over 48 up to and including 52 Kg Half Middleweight up to and including 48 Kg POSTCARD FROM LONDON You have just spent two weeks in London. -

Men's 100M Diamond Discipline - Heat 1 20.07.2019

Men's 100m Diamond Discipline - Heat 1 20.07.2019 Start list 100m Time: 14:35 Records Lane Athlete Nat NR PB SB 1 Julian FORTE JAM 9.58 9.91 10.17 WR 9.58 Usain BOLT JAM Berlin 16.08.09 2 Adam GEMILI GBR 9.87 9.97 10.11 AR 9.86 Francis OBIKWELU POR Athina 22.08.04 3 Yuki KOIKE JPN 9.97 10.04 10.04 =AR 9.86 Jimmy VICAUT FRA Paris 04.07.15 =AR 9.86 Jimmy VICAUT FRA Montreuil-sous-Bois 07.06.16 4 Arthur CISSÉ CIV 9.94 9.94 10.01 NR 9.87 Linford CHRISTIE GBR Stuttgart 15.08.93 5 Yohan BLAKE JAM 9.58 9.69 9.96 WJR 9.97 Trayvon BROMELL USA Eugene, OR 13.06.14 6 Akani SIMBINE RSA 9.89 9.89 9.95 MR 9.78 Tyson GAY USA 13.08.10 7 Andrew ROBERTSON GBR 9.87 10.10 10.17 DLR 9.69 Yohan BLAKE JAM Lausanne 23.08.12 8 Oliver BROMBY GBR 9.87 10.22 10.22 SB 9.81 Christian COLEMAN USA Palo Alto, CA 30.06.19 9 Ojie EDOBURUN GBR 9.87 10.04 10.17 2019 World Outdoor list 9.81 -0.1 Christian COLEMAN USA Palo Alto, CA 30.06.19 Medal Winners Road To The Final 9.86 +0.9 Noah LYLES USA Shanghai 18.05.19 1 Christian COLEMAN (USA) 23 9.86 +0.8 Divine ODUDURU NGR Austin, TX 07.06.19 2018 - Berlin European Ch. -

The Olympic 100M Sprint

Exploring the winning data: the Olympic 100 m sprint Performances in athletic events have steadily improved since the Olympics first started in 1896. Chemists have contributed to these improvements in a number of ways. For example, the design of improved materials for clothing and equipment; devising and monitoring the best methods for training for particular sports and gaining a better understanding of how energy is released from our food so ensure that athletes get the best diet. Figure 1 Image of a gold medallist in the Olympic 100 m sprint. Year Winner (Men) Time (s) Winner (Women) Time (s) 1896 Thomas Burke (USA) 12.0 1900 Francis Jarvis (USA) 11.0 1904 Archie Hahn (USA) 11.0 1906 Archie Hahn (USA) 11.2 1908 Reginald Walker (S Africa) 10.8 1912 Ralph Craig (USA) 10.8 1920 Charles Paddock (USA) 10.8 1924 Harold Abrahams (GB) 10.6 1928 Percy Williams (Canada) 10.8 Elizabeth Robinson (USA) 12.2 1932 Eddie Tolan (USA) 10.38 Stanislawa Walasiewick (POL) 11.9 1936 Jessie Owens (USA) 10.30 Helen Stephens (USA) 11.5 1948 Harrison Dillard (USA) 10.30 Fanny Blankers-Koen (NED) 11.9 1952 Lindy Remigino (USA) 10.78 Majorie Jackson (USA) 11.5 1956 Bobby Morrow (USA) 10.62 Betty Cuthbert (AUS) 11.4 1960 Armin Hary (FRG) 10.32 Wilma Rudolph (USA) 11.3 1964 Robert Hayes (USA) 10.06 Wyomia Tyus (USA) 11.2 1968 James Hines (USA) 9.95 Wyomia Tyus (USA) 11.08 1972 Valeriy Borzov (USSR) 10.14 Renate Stecher (GDR) 11.07 1976 Hasely Crawford (Trinidad) 10.06 Anneqret Richter (FRG) 11.01 1980 Allan Wells (GB) 10.25 Lyudmila Kondratyeva (USA) 11.06 1984 Carl Lewis (USA) 9.99 Evelyn Ashford (USA) 10.97 1988 Carl Lewis (USA) 9.92 Florence Griffith-Joyner (USA) 10.62 1992 Linford Christie (GB) 9.96 Gail Devers (USA) 10.82 1996 Donovan Bailey (Canada) 9.84 Gail Devers (USA) 10.94 2000 Maurice Green (USA) 9.87 Eksterine Thanou (GRE) 11.12 2004 Justin Gatlin (USA) 9.85 Yuliya Nesterenko (BLR) 10.93 2008 Usain Bolt (Jam) 9.69 Shelly-Ann Fraser (Jam) 10.78 2012 Usain Bolt (Jam) 9.63 Shelly-Ann Fraser (Jam) 10.75 Exploring the wining data: 100 m sprint| 11-16 Questions 1.