Parliamentarians' Actions Within Petition Systems: Their Impact on Public Perceptions of Fairness*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

3347 Business Paper

3347 PROOF LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY 2019-20-21 FIRST SESSION OF THE FIFTY-SEVENTH PARLIAMENT BUSINESS PAPER No. 95 TUESDAY 11 MAY 2021 GOVERNMENT BUSINESS ORDERS OF THE DAY— 1 Environmental Planning and Assessment Amendment (Territorial Limits) Bill; resumption of the adjourned debate on the motion of Mr Rob Stokes, "That this bill be now read a second time". (Introduced 24 October 2019—Mr Paul Scully). 2 Firearms and Weapons Legislation Amendment (Criminal Use) Bill; resumption of the adjourned debate on the motion of Mr David Elliott, "That this bill be now read a second time". (Introduced 26 February 2020— Ms Steph Cooke). 3 Prevention of Cruelty to Animals Amendment Bill; consideration of Legislative Council amendments. (Mr Adam Marshall). 4 Payroll Tax Amendment (Jobs Plus) Bill; resumption of the adjourned debate on the motion of Mr Dominic Perrottet, "That this bill be now read a second time". (Introduced 5 May 2021—Mr Paul Lynch). 5 Statute Law (Miscellaneous Provisions) Bill; resumption of the adjourned debate on the motion of Mr Mark Speakman, "That this bill be now read a second time". (Introduced 5 May 2021—Mr Paul Lynch). 6 Budget Estimates and related papers 2020-2021; resumption of the interrupted debate, on the motion of Mr Dominic Perrottet, "That this House take note of the Budget Estimates and related papers 2020-21". (Moved 19 November 2020—Mr Lee Evans speaking, 8 minutes remaining after obtaining an extension). 7 Address To Her Majesty The Queen; resumption of the adjourned debate on the motion of Ms Gladys Berejiklian. (Moved 5 May 2021—Mr Victor Dominello). -

Legislative Assembly- PROOF Page 1

Tuesday, 4 August 2020 Legislative Assembly- PROOF Page 1 LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY Tuesday, 4 August 2020 The Speaker (The Hon. Jonathan Richard O'Dea) took the chair at 12:00. The Speaker read the prayer and acknowledgement of country. [Notices of motions given.] Bills GAS LEGISLATION AMENDMENT (MEDICAL GAS SYSTEMS) BILL 2020 First Reading Bill introduced on motion by Mr Kevin Anderson, read a first time and printed. Second Reading Speech Mr KEVIN ANDERSON (Tamworth—Minister for Better Regulation and Innovation) (12:16:12): I move: That this bill be now read a second time. I am proud to introduce the Gas Legislation Amendment (Medical Gas Systems) Bill 2020. The bill delivers on the New South Wales Government's promise to introduce a robust and effective licensing regulatory system for persons who carry out medical gas work. As I said on 18 June on behalf of the Government in opposing the Hon. Mark Buttigieg's private member's bill, nobody wants to see a tragedy repeated like the one we saw at Bankstown-Lidcombe Hospital. As I undertook then, the Government has taken the steps necessary to provide a strong, robust licensing framework for those persons installing and working on medical gases in New South Wales. To the families of John Ghanem and Amelia Khan, on behalf of the Government I repeat my commitment that we are taking action to ensure no other families will have to endure as they have. The bill forms a key part of the Government's response to licensed work for medical gases that are supplied in medical facilities in New South Wales. -

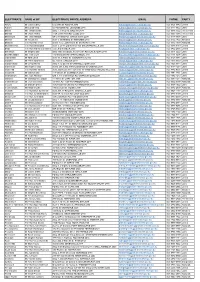

NSW Govt Lower House Contact List with Hyperlinks Sep 2019

ELECTORATE NAME of MP ELECTORATE OFFICE ADDRESS EMAIL PHONE PARTY Albury Mr Justin Clancy 612 Dean St ALBURY 2640 [email protected] (02) 6021 3042 Liberal Auburn Ms Lynda Voltz 92 Parramatta Rd LIDCOMBE 2141 [email protected] (02) 9737 8822 Labor Ballina Ms Tamara Smith Shop 1, 7 Moon St BALLINA 2478 [email protected] (02) 6686 7522 The Greens Balmain Mr Jamie Parker 112A Glebe Point Rd GLEBE 2037 [email protected] (02) 9660 7586 The Greens Bankstown Ms Tania Mihailuk 9A Greenfield Pde BANKSTOWN 2200 [email protected] (02) 9708 3838 Labor Barwon Mr Roy Butler Suite 1, 60 Maitland St NARRABRI 2390 [email protected] (02) 6792 1422 Shooters Bathurst The Hon Paul Toole Suites 1 & 2, 229 Howick St BATHURST 2795 [email protected] (02) 6332 1300 Nationals Baulkham Hills The Hon David Elliott Suite 1, 25-33 Old Northern Rd BAULKHAM HILLS 2153 [email protected] (02) 9686 3110 Liberal Bega The Hon Andrew Constance 122 Carp St BEGA 2550 [email protected] (02) 6492 2056 Liberal Blacktown Mr Stephen Bali Shop 3063 Westpoint, Flushcombe Rd BLACKTOWN 2148 [email protected] (02) 9671 5222 Labor Blue Mountains Ms Trish Doyle 132 Macquarie Rd SPRINGWOOD 2777 [email protected] (02) 4751 3298 Labor Cabramatta Mr Nick Lalich Suite 10, 5 Arthur St CABRAMATTA 2166 [email protected] (02) 9724 3381 Labor Camden Mr Peter Sidgreaves 66 John St CAMDEN 2570 [email protected] (02) 4655 3333 Liberal -

3119 Business Paper

3119 PROOF LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY 2019-20-21 FIRST SESSION OF THE FIFTY-SEVENTH PARLIAMENT BUSINESS PAPER No. 89 TUESDAY 23 MARCH 2021 GOVERNMENT BUSINESS ORDERS OF THE DAY— 1 Environmental Planning and Assessment Amendment (Territorial Limits) Bill; resumption of the adjourned debate on the motion of Mr Rob Stokes, "That this bill be now read a second time". (Introduced 24 October 2019—Mr Paul Scully). 2 Firearms and Weapons Legislation Amendment (Criminal Use) Bill; resumption of the adjourned debate on the motion of Mr David Elliott, "That this bill be now read a second time". (Introduced 26 February 2020— Ms Steph Cooke). 3 COVID-19 Recovery Bill; resumption of the adjourned debate on the motion of Mr Dominic Perrottet, "That this bill be now read a second time". (Introduced 17 March 2021—Ms Janelle Saffin). 4 Mutual Recognition (New South Wales) Amendment Bill; resumption of the adjourned debate on the motion of Mr Dominic Perrottet, "That this bill be now read a second time". (Introduced 17 March 2021— Ms Sophie Cotsis). 5 Real Property Amendment (Certificates of Title) Bill; resumption of the adjourned debate on the motion of Mr Victor Dominello, "That this bill be now read a second time". (Introduced 17 March 2021—Ms Sophie Cotsis). 6 Local Government Amendment Bill; resumption of the adjourned debate on the motion of Mrs Shelley Hancock, "That this bill be now read a second time". (Introduced 17 March 2021—Mr Greg Warren). 7 Civil Liability Amendment (Child Abuse) Bill; resumption of the adjourned debate on the motion of Mr Mark Speakman, "That this bill be now read a second time". -

Adequacy of Existing Residential Care Arrangements Available for Young

YOUNG PEOPLE WITH DISABILITIES SUPPORT SERVICES Discussion on Petition Signed by 10,000 or More Persons Mr ANDREW CONSTANCE (Bega—Minister for Finance and Services) [4.31 p.m.]: I acknowledge the representatives of the Brain Injury Association who are in the gallery today and thank the association for the enormous contribution it makes to raising awareness about brain injury in our community. In particular, I recognise the organisation that collected well over 10,000 signatures on this petition. I note that the shadow Minister, Barbara Perry, is in the Chamber this afternoon. The bottom line is that some issues are well and truly above and beyond politics. This is without doubt one of those issues. For too long both sides of politics have failed. They have failed to invest in the necessary pathways for people with acquired brain injury and failed to deal with the challenge presented by the interface between the disability and health sectors. We must recognise that many people who have brain injuries are faced with accommodation options that, unfortunately, will never be acceptable for their needs. It would not matter if it involved a nursing home or a rehabilitation bed in a hospital setting; the bottom line is that it is time for change. This has a profound impact on the daily lives and rehabilitation of those individuals who are forced to live in these types of accommodation. We have to have change. The reforms in the enabling legislation that is before the New South Wales Parliament to facilitate a transition to the National Disability Insurance Scheme must be rolled out carefully, in particular, the health and disability provisions for those with a brain injury. -

Legislative Assembly- PROOF Page 1

Thursday, 22 October 2020 Legislative Assembly- PROOF Page 1 LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY Thursday, 22 October 2020 The Speaker (The Hon. Jonathan Richard O'Dea) took the chair at 09:30. The Speaker read the prayer and acknowledgement of country. Announcements THOUGHT LEADERSHIP BREAKFAST The SPEAKER: I inform the House that we had two outstanding leaders of Indigenous heritage at our Thought Leadership breakfast this morning. I thank all those members who attended that event. In particular I thank our guest speakers: Tanya Denning-Allman, the director of Indigenous content at SBS, and Benson Saulo, the incoming Consul-General to the United States, based in Houston. I thank both of them and note we will have another event in November. [Notices of motions given.] Bills STRONGER COMMUNITIES LEGISLATION AMENDMENT (DOMESTIC VIOLENCE) BILL 2020 First Reading Bill introduced on motion by Mr Mark Speakman, read a first time and printed. Second Reading Speech Mr MARK SPEAKMAN (Cronulla—Attorney General, and Minister for the Prevention of Domestic Violence) (09:46:44): I move: That this bill be now read a second time. The Stronger Communities Legislation Amendment (Domestic Violence) Bill 2020 introduces amendments to support procedural improvements and to close gaps in the law that have become apparent. Courts can be a daunting place for victims of domestic and family violence. The processes can be overwhelming. Domestic violence is a complex crime like no other because of the intimate relationships between perpetrators and victims. Those close personal connections intertwine complainants and defendants in ways that maintain a callous grip on victims. This grip can silence reports of abuse, delay reports when victims are brave enough to come forward, and intimidate victims to discontinue cooperating with prosecutions. -

2173 Business Paper

2173 LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY 2019-20 FIRST SESSION OF THE FIFTY-SEVENTH PARLIAMENT BUSINESS PAPER No. 64 THURSDAY 17 SEPTEMBER 2020 GOVERNMENT BUSINESS NOTICES OF MOTION— 1 DR GEOFF LEE to move— That a bill be introduced for an Act to amend the Sporting Venues Authorities Act 2008 to reconstitute Venues NSW and dissolve the Sydney Cricket Ground Trust; to repeal and make consequential or related amendments to certain legislation. (Sporting Venues Authorities Amendment (Venues NSW) Bill). (Notice given 15 September 2020) ORDERS OF THE DAY— 1 Environmental Planning and Assessment Amendment (Territorial Limits) Bill; resumption of the adjourned debate on the motion of Mr Rob Stokes, "That this bill be now read a second time". (Introduced 24 October 2019—Mr Paul Scully). 2 Firearms and Weapons Legislation Amendment (Criminal Use) Bill; resumption of the adjourned debate on the motion of Mr David Elliott, "That this bill be now read a second time". (Introduced 26 February 2020— Ms Steph Cooke). 3 Strata Schemes Management Amendment (Sustainability Infrastructure) Bill: consideration of the Legislative Council Amendment. (Mr Kevin Anderson). 2174 BUSINESS PAPER Thursday 17 September 2020 4 Budget Estimates and related papers 2019-2020; resumption of the interrupted debate, on the motion of Mr Dominic Perrottet, "That this House take note of the Budget Estimates and related papers 2019-20". (Moved 20 June 2019—Ms Steph Cooke speaking, 2 minutes remaining after obtaining an extension). 5 Superannuation Legislation Amendment Bill; resumption of the adjourned debate on the motion of Mr Dominic Perrottet, "That this bill be now read a second time". (Introduced 16 September 2020—Mr Edmond Atalla). -

Lee Evans MP MEMBER for HEATHCOTE

Lee Evans MP MEMBER FOR HEATHCOTE Community Newsletter – July 2017 THE HEATHCOTE HERALD from This budget issue of the Heathcote Herald highlights the ongoing commitment of the NSW Liberal and Nationals Government to the people of NSW. Six years of responsible fiscal management has allowed the government to deliver projects that support our everyday lives through investment in health, education, transport and by assisting families with the cost of living. The NSW Budget 2017/18 delivers for local communities with some of the projects for Heathcote highlighted on page 3. Contact my office if you would like more information about these projects or others that are planned for Heathcote. Earlier this year I was pleased to host Premier Gladys Berejiklian, Minister for Planning Anthony Roberts and CEO of The Greater Sydney Commission Sarah Hill to hear firsthand from community representatives their comments and suggestions regarding housing affordability in NSW. The subsequent announcement of the Housing Affordability Package is yet another example of our government listening and responding to the issues that are important to you. July 2017 NSW NSW Premier Budget 2017 LIBERALS Stronger Communities, Stronger NSW Gladys Berejiklian and Lee Evans MP are working The Hon Dominic Perrottet MP hard for our local area The Hon Gladys Berejiklian MP Treasurer of New South Wales Premier of New South Wales Dear resident, With the NSW economy leading the nation and our Budget in surplus, the NSW Government is investing the benefits of the State’s success back into local communities right across NSW. The NSW Budget 2017-18 delivers more than ever before on the things that matter: health, education, roads and transport, support for families, help for those who need it WATTAMOLLA SUTHERLAND OTFORD most, and the right conditions for businesses to grow. -

Legislation Review Digest No. 17 of 57 I Title

PARLIAMENT OF NEW SOUTH WALES Legislation Review Committee LEGISLATION REVIEW DIGEST NO. 17/57 – 4 August 2020 New South Wales Parliamentary Library cataloguing-in-publication data: New South Wales. Parliament. Legislative Assembly. Legislation Review Committee Legislation Review Digest, Legislation Review Committee, Parliament NSW [Sydney, NSW]: The Committee, 2020, 80pp 30cm Chair: Felicity Wilson MP 4 August 2020 ISSN 1448-6954 1. Legislation Review Committee – New South Wales 2. Legislation Review Digest No. 17 of 57 I Title. II Series: New South Wales. Parliament. Legislation Review Committee Digest; No. 17 of 57 The motto of the coat of arms for the state of New South Wales is “Orta recens quam pura nites”. It is written in Latin and means “newly risen, how brightly you shine”. LEGISLATION REVIEW DIGEST Contents Membership _____________________________________________________________ ii Guide to the Digest _______________________________________________________ iii Conclusions ______________________________________________________________iv PART ONE – BILLS ______________________________________________________________________ 1 1. CASINO CONTROL AMENDMENT (INQUIRIES) BILL 2020 _________________________________ 1 2. PRIVACY AND PERSONAL INFORMATION PROTECTION AMENDMENT (SERVICE PROVIDERS) BILL 2020* _________________________________________________________________________ 7 3. STRATA SCHEMES MANAGEMENT AMENDMENT (SUSTAINABILITY INFRASTRUCTURE) BILL 2020 8 4. WATER MANAGEMENT AMENDMENT (WATER RIGHTS TRANSPARENCY) BILL 2020 (NO 2)* -

Standing Orders and Procedure Committee

LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY STANDING ORDERS AND PROCEDURE COMMITTEE Modernisation and reform of practices and procedures: ePetitions sessional orders Interim report 3/57 – June 2020 New South Wales Parliamentary Library cataloguing-in-publication data: New South Wales. Parliament. Legislative Assembly. Standing Orders and Procedure Committee. Modernisation and reform of practices and procedures: ePetitions sessional orders / Legislative Assembly, Standing Orders and Procedure Committee. [Sydney, N.S.W.] : the Committee, 2020. – 1 online resource (15 pages). (Report ; no. 3/57) ISBN: 978-1-921012-91-4 1. New South Wales. Parliament. Legislative Assembly—Rules and practice. 2. Parliamentary practice—New South Wales. I. Title. II. O'Dea, Jonathan. III. Series: New South Wales. Parliament. Legislative Assembly. Standing Orders and Procedure Committee. Report ; no. 3/57. 328.944 (DDC22) The motto of the coat of arms for the state of New South Wales is “Orta recens quam pura nites”. It is written in Latin and means “newly risen, how brightly you shine”. MODERNISATION AND REFORM: ePETITIONS SESSIONAL ORDERS Contents Membership ________________________________________________________________ IV Terms of reference ____________________________________________________________ V Speaker’s foreword __________________________________________________________ VI Recommendation ____________________________________________________________ VII Chapter One – ePetitions sessional orders _________________________________________ 1 Appendix One – Proposed ePetitions -

22 Apr 2020: Nsw, Legislation Review Committee

PARLIAMENT OF NEW SOUTH WALES Legislation Review Committee LEGISLATION REVIEW DIGEST NO. 12/57 – 22 April 2020 New South Wales Parliamentary Library cataloguing-in-publication data: New South Wales. Parliament. Legislative Assembly. Legislation Review Committee Legislation Review Digest, Legislation Review Committee, Parliament NSW [Sydney, NSW]: The Committee, 2020, 45pp 30cm Chair: Felicity Wilson MP 22 April 2020 ISSN 1448-6954 1. Legislation Review Committee – New South Wales 2. Legislation Review Digest No. 12 of 57 I Title. II Series: New South Wales. Parliament. Legislation Review Committee Digest; No. 12 of 57 The motto of the coat of arms for the state of New South Wales is “Orta recens quam pura nites”. It is written in Latin and means “newly risen, how brightly you shine”. LEGISLATION REVIEW DIGEST Contents Membership _____________________________________________________________ ii Guide to the Digest _______________________________________________________ iii Conclusions ______________________________________________________________iv PART ONE – BILLS ______________________________________________________________________ 1 1. COVID-19 LEGISLATION (EMERGENCY MEASURES) BILL 2020 _____________________________ 1 2. TREASURY LEGISLATION AMENDMENT (COVID-19) BILL 2020 ____________________________ 27 APPENDIX ONE – FUNCTIONS OF THE COMMITTEE __________________________________________ 29 22 APRIL 2020 i LEGISLATION REVIEW COMMITTEE Membership CHAIR Ms Felicity Wilson MP, Member for North Shore DEPUTY CHAIR The Hon Trevor Khan MLC -

Standing Orders and Procedure Committee

LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY OF NEW SOUTH WALES Standing Orders and Procedure Committee REPORT 1/57 – AUGUST 2019 MODERNISATION AND REFORM OF PRACTICES AND PROCEDURES INTERIM REPORT LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY STANDING ORDERS AND PROCEDURE COMMITTEE Modernisation and reform of practices and procedures Interim report 1/57 – August 2019 New South Wales Parliamentary Library cataloguing-in-publication data: New South Wales. Parliament. Legislative Assembly. Standing Orders and Procedure Committee. Modernisation and reform of practices and procedures / Legislative Assembly, Standing Orders and Procedure Committee. [Sydney, N.S.W.] : the Committee, 2019. – 1 online resource (35 pages). (Report ; no. 1/57) ISBN: 978-1-921012-81-5 1. New South Wales. Parliament. Legislative Assembly—Rules and practice. 2. Parliamentary practice—New South Wales. I. Title. II. O'Dea, Jonathan. III. Series: New South Wales. Parliament. Legislative Assembly. Standing Orders and Procedure Committee. Report ; no. 1/57. 328.944 (DDC22) The motto of the coat of arms for the state of New South Wales is “Orta recens quam pura nites”. It is written in Latin and means “newly risen, how brightly you shine”. MODERNISATION AND REFORM Contents Membership _________________________________________________________________ ii Tems of reference ___________________________________________________________ iii Speaker’s foreword ___________________________________________________________iv Recommendation _____________________________________________________________vi Chapter One – Changes to the Sessional Orders _____________________________________ 1 Appendix One – Extracts from Minutes ___________________________________________ 24 i MODERNISATION AND REFORM Membership CHAIR The Hon. Jonathan O'Dea MP MEMBERS The Hon. Andrew Constance MP Ms Steph Cooke MP Mr Mark Coure MP Mr Adam Crouch MP Mr Michael Daley MP Mr Lee Evans MP Mr Nick Lalich MP (9 May 2019 – 30 July 2019) Mr Paul Lynch MP (9 May 2019 – 30 July 2019) Mr Ryan Park MP (from 30 July 2019) Mr Greg Piper MP Ms Anna Watson MP (from 30 July 2019) The Hon.