A Question of Patriotism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reviewing and Evaluating the Direct Elections to the Legislative Council and the Transformation of Political Parties in Hong Kong, 1991-2016

Journal of US-China Public Administration, August 2016, Vol. 13, No. 8, 499-517 doi: 10.17265/1548-6591/2016.08.001 D DAVID PUBLISHING Reviewing and Evaluating the Direct Elections to the Legislative Council and the Transformation of Political Parties in Hong Kong, 1991-2016 Chung Fun Steven Hung The Education University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong After direct elections were instituted in Hong Kong, politicization inevitably followed democratization. This paper intends to evaluate how political parties’ politics happened in Hong Kong’s recent history. The research was conducted through historical comparative analysis, with the context of Hong Kong during the sovereignty transition and the interim period of democratization being crucial. For the implementation of “one country, two systems”, political democratization was hindered and distinct political scenarios of Hong Kong’s transformation were made. The democratic forces had no alternative but to seek more radicalized politics, which caused a decisive fragmentation of the local political parties where the establishment camp was inevitable and the democratic blocs were split into many more small groups individually. It is harmful. It is not conducive to unity and for the common interests of the publics. This paper explores and evaluates the political history of Hong Kong and the ways in which the limited democratization hinders the progress of Hong Kong’s transformation. Keywords: election politics, historical comparative, ruling, democratization The democratizing element of the Hong Kong political system was bounded within the Legislative Council under the principle of the separation of powers of the three governing branches, Executive, Legislative, and Judicial. Popular elections for the Hong Kong legislature were introduced and implemented for 25 years (1991-2016) and there were eight terms of general elections for the Legislative Council. -

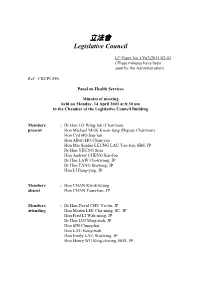

Minutes Have Been Seen by the Administration)

立法會 Legislative Council LC Paper No. CB(2)2011/02-03 (These minutes have been seen by the Administration) Ref : CB2/PL/HS Panel on Health Services Minutes of meeting held on Monday, 14 April 2003 at 8:30 am in the Chamber of the Legislative Council Building Members : Dr Hon LO Wing-lok (Chairman) present Hon Michael MAK Kwok-fung (Deputy Chairman) Hon Cyd HO Sau-lan Hon Albert HO Chun-yan Hon Mrs Sophie LEUNG LAU Yau-fun, SBS, JP Dr Hon YEUNG Sum Hon Andrew CHENG Kar-foo Dr Hon LAW Chi-kwong, JP Dr Hon TANG Siu-tong, JP Hon LI Fung-ying, JP Members : Hon CHAN Kwok-keung absent Hon CHAN Yuen-han, JP Members : Dr Hon David CHU Yu-lin, JP attending Hon Martin LEE Chu-ming, SC, JP Hon Fred LI Wah-ming, JP Dr Hon LUI Ming-wah, JP Hon SIN Chung-kai Hon LAU Kong-wah Hon Emily LAU Wai-hing, JP Hon Henry WU King-cheong, BBS, JP - 2 - Public Officers : Mr Thomas YIU, JP attending Deputy Secretary for Health, Welfare and Food Mr Nicholas CHAN Assistant Secretary for Health, Welfare and Food Dr P Y LAM, JP Deputy Director of Health Dr W M KO, JP Director (Professional Services & Public Affairs) Hospital Authority Dr Thomas TSANG Consultant Clerk in : Ms Doris CHAN attendance Chief Assistant Secretary (2) 4 Staff in : Ms Joanne MAK attendance Senior Assistant Secretary (2) 2 I. Confirmation of minutes (LC Paper No. CB(2)1735/02-03) The minutes of the regular meeting on 10 March 2003 were confirmed. -

I Am Sorry. Would Members Please Deal with One Piece of Business. It Is Now Eight O’Clock and Under Standing Order 8(2) This Council Should Now Adjourn

4920 HONG KONG LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL ― 29 June 1994 8.00 pm PRESIDENT: I am sorry. Would Members please deal with one piece of business. It is now eight o’clock and under Standing Order 8(2) this Council should now adjourn. ATTORNEY GENERAL: Mr President, with your consent, I move that Standing Order 8(2) should be suspended so as to allow the Council’s business this evening to be concluded. Question proposed, put and agreed to. Council went into Committee. CHAIRMAN: Council is now in Committee and is suspended until 15 minutes to nine o’clock. 8.56 pm CHAIRMAN: Committee will now resume. MR MARTIN LEE (in Cantonese): Mr Chairman, thank you for adjourning the debate on my motion so that Members could have a supper break. I hope I can secure a greater chance of success if they listen to my speech after dining. Mr Chairman, on behalf of the United Democrats of Hong Kong (UDHK), I move the amendments to clause 22 except item 12 of schedule 2. The amendments have already been set out under my name in the paper circulated to Members. Mr Chairman, before I make my speech, I would like to raise a point concerning Mr Jimmy McGREGOR because he was quite upset when he heard my previous speech. He hoped that I could clarify one point. In fact, I did not mean that all the people in the commercial sector had not supported democracy. If all the voters in the commercial sector had not supported democracy, Mr Jimmy McGREGOR would not have been returned in the 1988 and 1991 elections. -

The Basic Law and Democratization in Hong Kong

THE BASIC LAW AND DEMOCRATIZATION IN HONG KONG Michael C. Davis† I. Introduction Hong Kong’s status as a Special Administrative Region of China has placed it on the foreign policy radar of most countries having relations with China and interests in Asia. This interest in Hong Kong has encouraged considerable inter- est in Hong Kong’s founding documents and their interpretation. Hong Kong’s constitution, the Hong Kong Basic Law (“Basic Law”), has sparked a number of debates over democratization and its pace. It is generally understood that greater democratization will mean greater autonomy and vice versa, less democracy means more control by Beijing. For this reason there is considerable interest in the politics of interpreting Hong Kong’s Basic Law across the political spectrum in Hong Kong, in Beijing and in many foreign capitals. This interest is en- couraged by appreciation of the fundamental role democratization plays in con- stitutionalism in any society. The dynamic interactions of local politics and Beijing and foreign interests produce the politics of constitutionalism in Hong Kong. Understanding the Hong Kong political reform debate is therefore impor- tant to understanding the emerging status of both Hong Kong and China. This paper considers the politics of constitutional interpretation in Hong Kong and its relationship to developing democracy and sustaining Hong Kong’s highly re- garded rule of law. The high level of popular support for democratic reform in Hong Kong is a central feature of the challenge Hong Kong poses for China. Popular Hong Kong values on democracy and human rights have challenged the often undemocratic stance of the Beijing government and its supporters. -

Entire Dissertation Noviachen Aug2021.Pages

Documentary as Alternative Practice: Situating Contemporary Female Filmmakers in Sinophone Cinemas by Novia Shih-Shan Chen M.F.A., Ohio University, 2008 B.F.A., National Taiwan University, 2003 Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Gender, Sexuality, and Women’s Studies Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences © Novia Shih-Shan Chen 2021 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY SUMMER 2021 Copyright in this work rests with the author. Please ensure that any reproduction or re-use is done in accordance with the relevant national copyright legislation. Declaration of Committee Name: Novia Shih-Shan Chen Degree: Doctor of Philosophy Thesis title: Documentary as Alternative Practice: Situating Contemporary Female Filmmakers in Sinophone Cinemas Committee: Chair: Jen Marchbank Professor, Department of Gender, Sexuality and Women’s Studies Helen Hok-Sze Leung Supervisor Professor, Department of Gender, Sexuality and Women’s Studies Zoë Druick Committee Member Professor, School of Communication Lara Campbell Committee Member Professor, Department of Gender, Sexuality and Women’s Studies Christine Kim Examiner Associate Professor, Department of English The University of British Columbia Gina Marchetti External Examiner Professor, Department of Comparative Literature The University of Hong Kong ii Abstract Women’s documentary filmmaking in Sinophone cinemas has been marginalized in the film industry and understudied in film studies scholarship. The convergence of neoliberalism, institutionalization of pan-Chinese documentary films and the historical marginalization of women’s filmmaking in Taiwan, Hong Kong, and the People’s Republic of China (PRC), respectively, have further perpetuated the marginalization of documentary films by local female filmmakers. -

Hong Kong's Endgame and the Rule of Law (Ii): the Battle Over "The People" and the Business Community in the Transition to Chinese Rule

HONG KONG'S ENDGAME AND THE RULE OF LAW (II): THE BATTLE OVER "THE PEOPLE" AND THE BUSINESS COMMUNITY IN THE TRANSITION TO CHINESE RULE JACQUES DELISLE* & KEVIN P. LANE- 1. INTRODUCTION Transitional Hong Kong's endgame formally came to a close with the territory's reversion to Chinese rule on July 1, 1997. How- ever, a legal and institutional order and a "rule of law" for Chi- nese-ruled Hong Kong remain works in progress. They will surely bear the mark of the conflicts that dominated the final years pre- ceding Hong Kong's legal transition from British colony to Chinese Special Administrative Region ("S.A.R."). Those endgame conflicts reflected a struggle among adherents to rival conceptions of a rule of law and a set of laws and institutions that would be adequate and acceptable for Hong Kong. They unfolded in large part through battles over the attitudes and allegiance of "the Hong Kong people" and Hong Kong's business community. Hong Kong's Endgame and the Rule of Law (I): The Struggle over Institutions and Values in the Transition to Chinese Rule ("Endgame I") focused on the first aspect of this story. It examined the political struggle among members of two coherent, but not monolithic, camps, each bound together by a distinct vision of law and sover- t Special Series Reprint: Originally printed in 18 U. Pa. J. Int'l Econ. L. 811 (1997). Assistant Professor, University of Pennsylvania Law School. This Article is the second part of a two-part series. The first part appeared as Hong Kong's End- game and the Rule of Law (I): The Struggle over Institutions and Values in the Transition to Chinese Rule, 18 U. -

The Globalization of Chinese Food ANTHROPOLOGY of ASIA SERIES Series Editor: Grant Evans, University Ofhong Kong

The Globalization of Chinese Food ANTHROPOLOGY OF ASIA SERIES Series Editor: Grant Evans, University ofHong Kong Asia today is one ofthe most dynamic regions ofthe world. The previously predominant image of 'timeless peasants' has given way to the image of fast-paced business people, mass consumerism and high-rise urban conglomerations. Yet much discourse remains entrenched in the polarities of 'East vs. West', 'Tradition vs. Change'. This series hopes to provide a forum for anthropological studies which break with such polarities. It will publish titles dealing with cosmopolitanism, cultural identity, representa tions, arts and performance. The complexities of urban Asia, its elites, its political rituals, and its families will also be explored. Dangerous Blood, Refined Souls Death Rituals among the Chinese in Singapore Tong Chee Kiong Folk Art Potters ofJapan Beyond an Anthropology of Aesthetics Brian Moeran Hong Kong The Anthropology of a Chinese Metropolis Edited by Grant Evans and Maria Tam Anthropology and Colonialism in Asia and Oceania Jan van Bremen and Akitoshi Shimizu Japanese Bosses, Chinese Workers Power and Control in a Hong Kong Megastore WOng Heung wah The Legend ofthe Golden Boat Regulation, Trade and Traders in the Borderlands of Laos, Thailand, China and Burma Andrew walker Cultural Crisis and Social Memory Politics of the Past in the Thai World Edited by Shigeharu Tanabe and Charles R Keyes The Globalization of Chinese Food Edited by David Y. H. Wu and Sidney C. H. Cheung The Globalization of Chinese Food Edited by David Y. H. Wu and Sidney C. H. Cheung UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI'I PRESS HONOLULU Editorial Matter © 2002 David Y. -

立法會 Legislative Council

立法會 Legislative Council LC Paper No. CB(2)280/00-01 (These minutes have been seen by the Administration) Ref : CB2/BC/13/00 Legislative Council Bills Committee on Chief Executive Election Bill Minutes of the tenth meeting held on Thursday, 31 May 2001 at 8:30 am in the Chamber of the Legislative Council Building Members : Hon IP Kwok-him, JP (Chairman) Present Hon James TIEN Pei-chun, JP Hon David CHU Yu-lin Hon Martin LEE Chu-ming, SC, JP Hon NG Leung-sing Prof Hon NG Ching-fai Hon Margaret NG Hon CHEUNG Man-kwong Hon HUI Cheung-ching Dr Hon Philip WONG Yu-hong Hon Jasper TSANG Yok-sing, JP Hon Howard YOUNG, JP Dr Hon YEUNG Sum Hon Ambrose LAU Hon-chuen, JP Hon Emily LAU Wai-hing, JP Hon CHOY So-yuk Hon SZETO Wah Hon Timothy FOK Tsun-ting, SBS, JP Hon TAM Yiu-chung, GBS, JP Hon LEUNG Fu-wah, MH, JP Hon LAU Ping-cheung Hon Audrey EU Yuet-mee, SC, JP Members: Hon Andrew WONG Wang-fat, JP (Deputy Chairman) Absent Hon Cyd HO Sau-lan Ir Dr Hon Raymond HO Chung-tai, JP Hon Eric LI Ka-cheung, JP - 2 - Hon CHAN Yuen-han Hon Michael MAK Kwok-fung Hon Abraham SHEK Lai-him, JP Hon Tommy CHEUNG Yu-yan, JP Dr Hon LO Wing-lok Public Officers : Mr Michael M Y SUEN, GBS, JP Attending Secretary for Constitutional Affairs Mr Robin IP Deputy Secretary for Constitutional Affairs Ms Doris HO Principal Assistant Secretary for Constitutional Affairs Mr Bassanio SO Principal Assistant Secretary for Constitutional Affairs Mr James O'NEIL Deputy Solicitor General (Constitutional) Mr Gilbert MO Deputy Law Draftsman (Bilingual Drafting & Administration) Ms Phyllis KO Senior Assistant Law Draftsman Clerk in : Mrs Percy MA Attendance Chief Assistant Secretary (2)3 Staff in : Mr Stephen LAM Attendance Assistant Legal Adviser 4 Mr Paul WOO Senior Assistant Secretary (2)3 - 3 - Action Column I. -

The Brookings Institution Center for Northeast Asian Policy Studies

THE BROOKINGS INSTITUTION CENTER FOR NORTHEAST ASIAN POLICY STUDIES The 2004 Legislative Council Elections and Implications for U.S. Policy toward Hong Kong Wednesday, September 15, 2004 Introduction: RICHARD BUSH Director, Center for Northeast Asian Policy Studies The Brookings Institution Presenter: SONNY LO SHIU-HING Associate Professor of Political Science University of Waterloo Discussant: ELLEN BORK Deputy Director Project for the New American Century [TRANSCRIPT PREPARED FROM A TAPE RECORDING.] THE BROOKINGS INSTITUTION CENTER FOR NORTHEAST ASIAN POLICY STUDIES 1775 MASSACHUSETTS AVENUE, NW WASHINGTON, D.C. 20036 202-797-6307 P R O C E E D I N G S MR. BUSH: [In progress] I've long thought that politically Hong Kong plays a very important role in the Chinese political system because it can be, I think, a test bed, or a place to experiment on different political forums on how to run large Chinese cities in an open, competitive, and accountable way. So how Hong Kong's political development proceeds is very important for some larger and very significant issues for the Chinese political system as a whole, and therefore the debate over democratization in Hong Kong is one that has significance that reaches much beyond the rights and political participation of the people there. The election that occurred last Sunday is a kind of punctuation mark in that larger debate over democratization, and we're very pleased to have two very qualified people to talk to us today. The first is Professor Sonny Lo Shiu-hing, who has just joined the faculty of the University of Waterloo in Canada. -

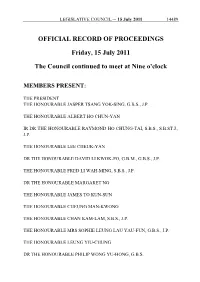

OFFICIAL RECORD of PROCEEDINGS Friday, 15 July

LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL ─ 15 July 2011 14489 OFFICIAL RECORD OF PROCEEDINGS Friday, 15 July 2011 The Council continued to meet at Nine o'clock MEMBERS PRESENT: THE PRESIDENT THE HONOURABLE JASPER TSANG YOK-SING, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE ALBERT HO CHUN-YAN IR DR THE HONOURABLE RAYMOND HO CHUNG-TAI, S.B.S., S.B.ST.J., J.P. THE HONOURABLE LEE CHEUK-YAN DR THE HONOURABLE DAVID LI KWOK-PO, G.B.M., G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE FRED LI WAH-MING, S.B.S., J.P. DR THE HONOURABLE MARGARET NG THE HONOURABLE JAMES TO KUN-SUN THE HONOURABLE CHEUNG MAN-KWONG THE HONOURABLE CHAN KAM-LAM, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE MRS SOPHIE LEUNG LAU YAU-FUN, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE LEUNG YIU-CHUNG DR THE HONOURABLE PHILIP WONG YU-HONG, G.B.S. 14490 LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL ─ 15 July 2011 THE HONOURABLE WONG YUNG-KAN, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE LAU KONG-WAH, J.P. THE HONOURABLE LAU WONG-FAT, G.B.M., G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE MIRIAM LAU KIN-YEE, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE EMILY LAU WAI-HING, J.P. THE HONOURABLE ANDREW CHENG KAR-FOO THE HONOURABLE TAM YIU-CHUNG, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE LI FUNG-YING, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE TOMMY CHEUNG YU-YAN, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE FREDERICK FUNG KIN-KEE, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE VINCENT FANG KANG, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE WONG KWOK-HING, M.H. -

PDF Full Report

Heightening Sense of Crises over Press Freedom in Hong Kong: Advancing “Shrinkage” 20 Years after Returning to China April 2018 YAMADA Ken-ichi NHK Broadcasting Culture Research Institute Media Research & Studies _____________________________ *This article is based on the same authors’ article Hong Kong no “Hodo no Jiyu” ni Takamaru Kikikan ~Chugoku Henkan kara 20nen de Susumu “Ishuku”~, originally published in the December 2017 issue of “Hoso Kenkyu to Chosa [The NHK Monthly Report on Broadcast Research]”. Full text in Japanese may be accessed at http://www.nhk.or.jp/bunken/research/oversea/pdf/20171201_7.pdf 1 Introduction Twenty years have passed since Hong Kong was returned to China from British rule. At the time of the 1997 reversion, there were concerns that Hong Kong, which has a laissez-faire market economy, would lose its economic vigor once the territory is put under the Chinese Communist Party’s one-party rule. But the Hong Kong economy has achieved generally steady growth while forming closer ties with the mainland. However, new concerns are rising that the “One Country, Two Systems” principle that guarantees Hong Kong a different social system from that of China is wavering and press freedom, which does not exist in the mainland and has been one of the attractions of Hong Kong, is shrinking. On the rankings of press freedom compiled by the international journalists’ group Reporters Without Borders, Hong Kong fell to 73rd place in 2017 from 18th in 2002.1 This article looks at how press freedom has been affected by a series of cases in the Hong Kong media that occurred during these two decades, in line with findings from the author’s weeklong field trip in mid-September 2017. -

Beijing's Visible Hand

China Perspectives 2012/2 | 2012 Mao Today: A Political Icon for an Age of Prosperity Beijing’s Visible Hand Power struggles and media meddling in the Hong Kong chief executive election Karita Kan Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/chinaperspectives/5896 DOI: 10.4000/chinaperspectives.5896 ISSN: 1996-4617 Publisher Centre d'étude français sur la Chine contemporaine Printed version Date of publication: 4 June 2012 Number of pages: 81-84 ISSN: 2070-3449 Electronic reference Karita Kan, « Beijing’s Visible Hand », China Perspectives [Online], 2012/2 | 2012, Online since 30 June 2012, connection on 15 September 2020. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/chinaperspectives/ 5896 © All rights reserved Current affairs China perspectives Beijing’s Visible Hand Power struggles and political interventions in the 2012 Hong Kong chief executive election KARITA KAN ong Kong’s next chief executive was revealed on 25 March 2012, reignited frenzied probes into Tang’s extra-marital affairs and added fuel to when the 1,193-member election committee, made up largely of incriminating remarks about his dishonesty, infidelity, and “emotional fault” Hbusiness leaders, professionals, and influential persons loyal to Bei - (ganqing queshi 感情缺失 ). jing, voted in majority for Leung Chun-ying. Leung defeated his main op - Commentator Willy Lam Wo-lap and Open University computing profes - ponent, former chief secretary for administration Henry Tang Ying-yen, by sor Li Tak-shing both raised the alarm that these “black materials” ( hei cailiao garnering 689 votes over the 285 that Tang received. The third candidate, 黑材料 ) might in fact have come from national security and intelligence Democratic Party chairman Albert Ho Chun-yan, secured only 76 votes.