Making Labour Laws in Semi-Authoritarian Hong Kong

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reviewing and Evaluating the Direct Elections to the Legislative Council and the Transformation of Political Parties in Hong Kong, 1991-2016

Journal of US-China Public Administration, August 2016, Vol. 13, No. 8, 499-517 doi: 10.17265/1548-6591/2016.08.001 D DAVID PUBLISHING Reviewing and Evaluating the Direct Elections to the Legislative Council and the Transformation of Political Parties in Hong Kong, 1991-2016 Chung Fun Steven Hung The Education University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong After direct elections were instituted in Hong Kong, politicization inevitably followed democratization. This paper intends to evaluate how political parties’ politics happened in Hong Kong’s recent history. The research was conducted through historical comparative analysis, with the context of Hong Kong during the sovereignty transition and the interim period of democratization being crucial. For the implementation of “one country, two systems”, political democratization was hindered and distinct political scenarios of Hong Kong’s transformation were made. The democratic forces had no alternative but to seek more radicalized politics, which caused a decisive fragmentation of the local political parties where the establishment camp was inevitable and the democratic blocs were split into many more small groups individually. It is harmful. It is not conducive to unity and for the common interests of the publics. This paper explores and evaluates the political history of Hong Kong and the ways in which the limited democratization hinders the progress of Hong Kong’s transformation. Keywords: election politics, historical comparative, ruling, democratization The democratizing element of the Hong Kong political system was bounded within the Legislative Council under the principle of the separation of powers of the three governing branches, Executive, Legislative, and Judicial. Popular elections for the Hong Kong legislature were introduced and implemented for 25 years (1991-2016) and there were eight terms of general elections for the Legislative Council. -

Official Record of Proceedings

LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL ─ 3 November 2010 1399 OFFICIAL RECORD OF PROCEEDINGS Wednesday, 3 November 2010 The Council met at Eleven o'clock MEMBERS PRESENT: THE PRESIDENT THE HONOURABLE JASPER TSANG YOK-SING, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE ALBERT HO CHUN-YAN IR DR THE HONOURABLE RAYMOND HO CHUNG-TAI, S.B.S., S.B.ST.J., J.P. THE HONOURABLE LEE CHEUK-YAN DR THE HONOURABLE DAVID LI KWOK-PO, G.B.M., G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE FRED LI WAH-MING, S.B.S., J.P. DR THE HONOURABLE MARGARET NG THE HONOURABLE JAMES TO KUN-SUN THE HONOURABLE CHEUNG MAN-KWONG THE HONOURABLE CHAN KAM-LAM, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE MRS SOPHIE LEUNG LAU YAU-FUN, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE LEUNG YIU-CHUNG DR THE HONOURABLE PHILIP WONG YU-HONG, G.B.S. 1400 LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL ─ 3 November 2010 THE HONOURABLE WONG YUNG-KAN, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE LAU KONG-WAH, J.P. THE HONOURABLE LAU WONG-FAT, G.B.M., G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE MIRIAM LAU KIN-YEE, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE EMILY LAU WAI-HING, J.P. THE HONOURABLE ANDREW CHENG KAR-FOO THE HONOURABLE TIMOTHY FOK TSUN-TING, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE TAM YIU-CHUNG, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE ABRAHAM SHEK LAI-HIM, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE LI FUNG-YING, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE TOMMY CHEUNG YU-YAN, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE FREDERICK FUNG KIN-KEE, S.B.S., J.P. -

Minutes of the 1St Meeting Held in Conference Room 1 of the Legislative Council Complex at 2:30 Pm on Friday, 14 October 2011

立法會 Legislative Council LC Paper No. CB(2) 97/11-12 Ref : CB2/H/5/10 House Committee of the Legislative Council Minutes of the 1st meeting held in Conference Room 1 of the Legislative Council Complex at 2:30 pm on Friday, 14 October 2011 Members present: Hon Miriam LAU Kin-yee, GBS, JP (Chairman) Hon Fred LI Wah-ming, SBS, JP (Deputy Chairman) Ir Dr Hon Raymond HO Chung-tai, SBS, S.B.St.J., JP Hon LEE Cheuk-yan Dr Hon David LI Kwok-po, GBM, GBS, JP Dr Hon Margaret NG Hon James TO Kun-sun Hon CHEUNG Man-kwong Hon CHAN Kam-lam, SBS, JP Hon Mrs Sophie LEUNG LAU Yau-fun, GBS, JP Hon LEUNG Yiu-chung Dr Hon Philip WONG Yu-hong, GBS Hon WONG Yung-kan, SBS, JP Hon LAU Kong-wah, JP Hon Emily LAU Wai-hing, JP Hon Andrew CHENG Kar-foo Hon TAM Yiu-chung, GBS, JP Hon Abraham SHEK Lai-him, SBS, JP Hon LI Fung-ying, SBS, JP Hon Tommy CHEUNG Yu-yan, SBS, JP Hon Audrey EU Yuet-mee, SC, JP Hon Vincent FANG Kang, SBS, JP Hon WONG Kwok-hing, MH Hon LEE Wing-tat Dr Hon Joseph LEE Kok-long, SBS, JP Hon Jeffrey LAM Kin-fung, GBS, JP Hon Andrew LEUNG Kwan-yuen, GBS, JP Hon CHEUNG Hok-ming, GBS, JP Hon WONG Ting-kwong, BBS, JP - 2 - Hon Ronny TONG Ka-wah, SC Hon CHIM Pui-chung Prof Hon Patrick LAU Sau-shing, SBS, JP Hon KAM Nai-wai, MH Hon Cyd HO Sau-lan Dr Hon LAM Tai-fai, BBS, JP Hon CHAN Hak-kan Hon Paul CHAN Mo-po, MH, JP Hon CHAN Kin-por, JP Dr Hon Priscilla LEUNG Mei-fun, JP Hon CHEUNG Kwok-che Hon WONG Sing-chi Hon WONG Kwok-kin, BBS Hon IP Wai-ming, MH Hon IP Kwok-him, GBS, JP Hon Mrs Regina IP LAU Suk-yee, GBS, JP Dr Hon PAN Pey-chyou Hon Paul TSE Wai-chun, -

Should Functional Constituency Elections in the Legislative Council Be

Hong Kong Diploma of Secondary Education Liberal Studies Independent Enquiry Study Report Standard Covering Page (for written reports and short written texts of non-written reports starting from 2017) Enquiry Question: Should Functional Constituency elections in the Legislative Council be abolished? Year of Examination: Name of Student: Class/ Group: Class Number: Number of words in the report: 3162 Notes: 1. Written reports should not exceed 4500 words. The reading time for non-written reports should not exceed 20 minutes and the short written texts accompanying non-written reports should not exceed 1000 words. The word count for written reports and the short written texts does not include the covering page, the table of contents, titles, graphs, tables, captions and headings of photos, punctuation marks, footnotes, endnotes, references, bibliography and appendices. 2. Candidates are responsible for counting the number of words in their reports and the short written texts and indicating it accurately on this covering page. 3. If the Independent Enquiry Study Report of a student is selected for review by the School-Based Assessment System, the school should ensure that the student’s name, class/ group and class number have been deleted from the report before submitting it to the Hong Kong Examinations and Assessment Authority. Schools should also ensure that the identities of both the schools and students are not disclosed in the reports. For non-written reports, the identities of the students and schools, including the appearance of the students, should be deleted. Sample 1 Table of Contents A. Problem Definition P.3 B. Relevant Concepts and Knowledge/ Facts/ Data P.5 C. -

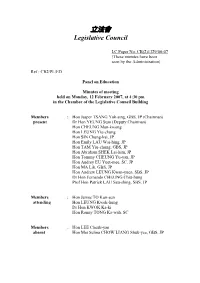

Minutes Have Been Seen by the Administration)

立法會 Legislative Council LC Paper No. CB(2)1329/06-07 (These minutes have been seen by the Administration) Ref : CB2/PL/ED Panel on Education Minutes of meeting held on Monday, 12 February 2007, at 4:30 pm in the Chamber of the Legislative Council Building Members : Hon Jasper TSANG Yok-sing, GBS, JP (Chairman) present Dr Hon YEUNG Sum (Deputy Chairman) Hon CHEUNG Man-kwong Hon LEUNG Yiu-chung Hon SIN Chung-kai, JP Hon Emily LAU Wai-hing, JP Hon TAM Yiu-chung, GBS, JP Hon Abraham SHEK Lai-him, JP Hon Tommy CHEUNG Yu-yan, JP Hon Audrey EU Yuet-mee, SC, JP Hon MA Lik, GBS, JP Hon Andrew LEUNG Kwan-yuen, SBS, JP Dr Hon Fernando CHEUNG Chiu-hung Prof Hon Patrick LAU Sau-shing, SBS, JP Members : Hon James TO Kun-sun attending Hon LEUNG Kwok-hung Dr Hon KWOK Ka-ki Hon Ronny TONG Ka-wah, SC Members : Hon LEE Cheuk-yan absent Hon Mrs Selina CHOW LIANG Shuk-yee, GBS, JP - 2 - Public Officers : Item IV attending Professor Maurice GALTON Consultant, Study on Small Class Teaching Ms Bernadette LINN, JP Deputy Secretary (Education and Manpower)2 Ms IP Ling-bik Principal Assistant Secretary (Education Commission and Planning) Ms CHUM Chui-che Senior Education Officer (Research and Test Development)2 Item V Professor Arthur LI, GBS, JP Secretary for Education and Manpower Mr Raymond WONG, JP Permanent Secretary for Education and Manpower Mrs Betty IP Deputy Secretary for Education and Manpower 4 Mr LEE Yuk-fai Principal Assistant Secretary (Professional Development and Training) Professor Edmond KO Chairman of the Committee on Teachers' Work Attendance by : Item IV invitation Hong Kong Professional Teachers' Union Miss SY On-na Vice-President Mr IP Kin-yuen Principal - 3 - Civic Party Ms Annie KI Hong Kong Island Branch District Development Officer Centre for Development and Research in Small Class Teaching, The Hong Kong Institute of Education Dr LAI Kwok-chan Head Professor Peter BLATCHFORD Professor, School of Psychology and Human Development in the Institute of Education, University of London S.K.H. -

OFFICIAL RECORD of PROCEEDINGS Wednesday, 12

LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL ─ 12 December 2012 3497 OFFICIAL RECORD OF PROCEEDINGS Wednesday, 12 December 2012 The Council met at Eleven o'clock MEMBERS PRESENT: THE PRESIDENT THE HONOURABLE JASPER TSANG YOK-SING, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE ALBERT HO CHUN-YAN THE HONOURABLE LEE CHEUK-YAN THE HONOURABLE JAMES TO KUN-SUN THE HONOURABLE CHAN KAM-LAM, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE LEUNG YIU-CHUNG DR THE HONOURABLE LAU WONG-FAT, G.B.M., G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE EMILY LAU WAI-HING, J.P. THE HONOURABLE TAM YIU-CHUNG, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE ABRAHAM SHEK LAI-HIM, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE TOMMY CHEUNG YU-YAN, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE VINCENT FANG KANG, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE WONG KWOK-HING, M.H. DR THE HONOURABLE JOSEPH LEE KOK-LONG, S.B.S., J.P. 3498 LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL ─ 12 December 2012 THE HONOURABLE JEFFREY LAM KIN-FUNG, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE ANDREW LEUNG KWAN-YUEN, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE WONG TING-KWONG, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE RONNY TONG KA-WAH, S.C. THE HONOURABLE CYD HO SAU-LAN THE HONOURABLE STARRY LEE WAI-KING, J.P. DR THE HONOURABLE LAM TAI-FAI, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE CHAN HAK-KAN, J.P. THE HONOURABLE CHAN KIN-POR, B.B.S., J.P. DR THE HONOURABLE PRISCILLA LEUNG MEI-FUN, J.P. DR THE HONOURABLE LEUNG KA-LAU THE HONOURABLE CHEUNG KWOK-CHE THE HONOURABLE WONG KWOK-KIN, B.B.S. -

The Brookings Institution Center for Northeast Asian Policy Studies

THE BROOKINGS INSTITUTION CENTER FOR NORTHEAST ASIAN POLICY STUDIES The 2004 Legislative Council Elections and Implications for U.S. Policy toward Hong Kong Wednesday, September 15, 2004 Introduction: RICHARD BUSH Director, Center for Northeast Asian Policy Studies The Brookings Institution Presenter: SONNY LO SHIU-HING Associate Professor of Political Science University of Waterloo Discussant: ELLEN BORK Deputy Director Project for the New American Century [TRANSCRIPT PREPARED FROM A TAPE RECORDING.] THE BROOKINGS INSTITUTION CENTER FOR NORTHEAST ASIAN POLICY STUDIES 1775 MASSACHUSETTS AVENUE, NW WASHINGTON, D.C. 20036 202-797-6307 P R O C E E D I N G S MR. BUSH: [In progress] I've long thought that politically Hong Kong plays a very important role in the Chinese political system because it can be, I think, a test bed, or a place to experiment on different political forums on how to run large Chinese cities in an open, competitive, and accountable way. So how Hong Kong's political development proceeds is very important for some larger and very significant issues for the Chinese political system as a whole, and therefore the debate over democratization in Hong Kong is one that has significance that reaches much beyond the rights and political participation of the people there. The election that occurred last Sunday is a kind of punctuation mark in that larger debate over democratization, and we're very pleased to have two very qualified people to talk to us today. The first is Professor Sonny Lo Shiu-hing, who has just joined the faculty of the University of Waterloo in Canada. -

Minutes Have Been Seen by the Administration)

立法會 Legislative Council LC Paper No. CB(2)2168/16-17 (These minutes have been seen by the Administration) Ref : CB2/PL/FE Panel on Food Safety and Environmental Hygiene Minutes of meeting held on Tuesday, 13 June 2017, at 2:30 pm in Conference Room 3 of the Legislative Council Complex Members : Dr Hon Helena WONG Pik-wan (Chairman) present Hon LAU Kwok-fan, MH (Deputy Chairman) Hon Tommy CHEUNG Yu-yan, GBS, JP Prof Hon Joseph LEE Kok-long, SBS, JP Hon WONG Ting-kwong, SBS, JP Hon Starry LEE Wai-king, SBS, JP Hon CHAN Hak-kan, BBS, JP Hon Claudia MO Hon Michael TIEN Puk-sun, BBS, JP Hon Steven HO Chun-yin, BBS Hon CHAN Chi-chuen Hon CHAN Han-pan, JP Dr Hon KWOK Ka-ki Hon KWOK Wai-keung Hon Christopher CHEUNG Wah-fung, SBS, JP Dr Hon Fernando CHEUNG Chiu-hung Dr Hon Elizabeth QUAT, JP Hon Martin LIAO Cheung-kong, SBS, JP Dr Hon CHIANG Lai-wan, JP Ir Dr Hon LO Wai-kwok, SBS, MH, JP Hon HO Kai-ming Hon SHIU Ka-fai Hon SHIU Ka-chun Hon Wilson OR Chong-shing, MH Dr Hon Pierre CHAN Hon Tanya CHAN Hon CHEUNG Kwok-kwan, JP Hon HUI Chi-fung Hon Kenneth LAU Ip-keung, MH, JP - 2 - Hon KWONG Chun-yu Hon Jeremy TAM Man-ho Dr Hon LAU Siu-lai Members : Hon LEUNG Yiu-chung absent Dr Hon Priscilla LEUNG Mei-fun, SBS, JP Hon WONG Kwok-kin, SBS, JP Hon LEUNG Kwok-hung Hon LEUNG Che-cheung, BBS, MH, JP Hon Alice MAK Mei-kuen, BBS, JP Hon Andrew WAN Siu-kin Hon CHU Hoi-dick Hon LUK Chung-hung Hon Nathan LAW Kwun-chung Dr Hon YIU Chung-yim [According to the Judgment of the Court of First Instance of the High Court on 14 July 2017, LEUNG Kwok-hung, Nathan LAW -

Legco Development Panel

(3) 22 April 2008 – Legislative Council Development Panel 立法會 Legislative Council LC Paper No. CB(1)1952/07-08 (These minutes have been seen by the Administration) Ref : CB1/PL/DEV/1 Panel on Development Minutes of meeting held on Tuesday, 22 April 2008, at 2:00 pm in Conference Room A of the Legislative Council Building Members present : Hon LAU Wong-fat, GBM, GBS, JP (Chairman) Prof Hon Patrick LAU Sau-shing, SBS, JP (Deputy Chairman) Hon James TIEN Pei-chun, GBS, JP Hon Albert HO Chun-yan Ir Dr Hon Raymond HO Chung-tai, SBS, S.B.St.J., JP Hon James TO Kun-sun Hon CHAN Kam-lam, SBS, JP Hon Miriam LAU Kin-yee, GBS, JP Hon CHOY So-yuk, JP Hon Timothy FOK Tsun-ting, GBS, JP Hon Albert CHAN Wai-yip Hon LEE Wing-tat Hon Daniel LAM Wai-keung, SBS, JP Hon Alan LEONG Kah-kit, SC Dr Hon KWOK Ka-ki Hon CHEUNG Hok-ming, SBS, JP Members attending: Hon CHAN Yuen-han, SBS, JP Hon WONG Kwok-hing, MH Members absent : Hon Mrs Sophie LEUNG LAU Yau-fun, GBS, JP Dr Hon Philip WONG Yu-hong, GBS Hon Abraham SHEK Lai-him, SBS, JP Public officers : Agenda item IV attending Mrs Carrie LAM Secretary for Development Mrs Susan MAK Deputy Secretary for Development (Planning & Lands)1 Miss Annie TAM Director of Lands Mr CHEUNG Hau-wai Director of Buildings Agenda item V Mrs Carrie LAM Secretary for Development Mrs Susan MAK Deputy Secretary for Development (Planning & Lands) 1 Mrs Ava NG Director of Planning Miss Ophelia WONG Deputy Director of Planning/District Agenda item VI Mrs Carrie LAM Secretary for Development Mrs Susan MAK Deputy Secretary for Development (Planning & Lands)1 Mr K K LING Principal Assistant Secretary (Planning & Lands) 5 Mrs Ava NG Director of Planning Mr YIP Sai-chor Head of Civil Engineering Office Clerk in attendance : Ms Anita SIT Chief Council Secretary (1)4 Staff in attendance : Mr WONG Siu-yee Senior Council Secretary (1)7 Ms Christina SHIU Legislative Assistant (1)7 *** V Urban Design Study for the New Central Harbourfront Stage 2 Public Engagement (LC Paper No. -

Minutes of the 27Th Meeting Held in Conference Room 1 of the Legislative Council Complex at 2:30 Pm on Friday, 31 May 2013

立法會 Legislative Council LC Paper No. CB(2)1278/12-13 Ref : CB2/H/5/12 House Committee of the Legislative Council Minutes of the 27th meeting held in Conference Room 1 of the Legislative Council Complex at 2:30 pm on Friday, 31 May 2013 Members present: Hon Andrew LEUNG Kwan-yuen, GBS, JP (Chairman) Hon Ronny TONG Ka-wah, SC (Deputy Chairman) Hon Albert HO Chun-yan Hon LEE Cheuk-yan Hon James TO Kun-sun Hon CHAN Kam-lam, SBS, JP Hon LEUNG Yiu-chung Hon Emily LAU Wai-hing, JP Hon TAM Yiu-chung, GBS, JP Hon Abraham SHEK Lai-him, SBS, JP Hon Tommy CHEUNG Yu-yan, SBS, JP Hon Frederick FUNG Kin-kee, SBS, JP Hon Vincent FANG Kang, SBS, JP Hon WONG Kwok-hing, MH Dr Hon Joseph LEE Kok-long, SBS, JP Hon Jeffrey LAM Kin-fung, GBS, JP Hon WONG Ting-kwong, SBS, JP Hon Cyd HO Sau-lan Hon Starry LEE Wai-king, JP Dr Hon LAM Tai-fai, SBS, JP Hon CHAN Hak-kan, JP Hon CHAN Kin-por, BBS, JP Dr Hon Priscilla LEUNG Mei-fun, JP Hon CHEUNG Kwok-che Hon WONG Kwok-kin, BBS Hon IP Kwok-him, GBS, JP Hon Mrs Regina IP LAU Suk-yee, GBS, JP Hon Paul TSE Wai-chun, JP Hon Alan LEONG Kah-kit, SC - 2 - Hon LEUNG Kwok-hung Hon Albert CHAN Wai-yip Hon WONG Yuk-man Hon Claudia MO Hon Michael TIEN Puk-sun, BBS, JP Hon James TIEN Pei-chun, GBS, JP Hon NG Leung-sing, SBS, JP Hon Steven HO Chun-yin Hon Frankie YICK Chi-ming Hon WU Chi-wai, MH Hon YIU Si-wing Hon Gary FAN Kwok-wai Hon MA Fung-kwok, SBS, JP Hon Charles Peter MOK Hon CHAN Chi-chuen Hon CHAN Han-pan Dr Hon Kenneth CHAN Ka-lok Hon CHAN Yuen-han, SBS, JP Hon LEUNG Che-cheung, BBS, MH, JP Hon Kenneth LEUNG Hon Alice -

Prospects for Democracy in Hong Kong: China's December 2007

Order Code RS22787 January 10, 2008 Prospects for Democracy in Hong Kong: China’s December 2007 Decision Michael F. Martin Analyst in Asian Trade and Finance Foreign Affairs, Defense, and Trade Summary The prospects for democratization in Hong Kong became clearer following a decision of the Standing Committee of China’s National People’s Congress (NPCSC) on December 29, 2007. The NPCSC’s decision effectively set the year 2017 as the earliest date for the direct election of Hong Kong’s Chief Executive and the year 2020 as the earliest date for the direct election of all members of Hong Kong’s Legislative Council (Legco). However, ambiguities in the language used by the NPCSC have contributed to differences in interpretation of its decision. According to Hong Kong’s current Chief Executive, Donald Tsang Yam-kuen, the decision sets a clear timetable for democracy in Hong Kong. However, representatives of Hong Kong’s “pro- democracy” parties believe the decision includes no solid commitment to democratization in Hong Kong. The NPCSC’s decision also established some guidelines for the process of election reform in Hong Kong, including what can and cannot be altered in the 2012 elections. Since China established the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region (HKSAR) on July 1, 1997, there have been questions about when and how the democratization of Hong Kong will take place.1 At present, Hong Kong’s Chief Executive is selected by an “Election Committee” of 800 largely appointed people, and its Legislative Council (Legco) consists of 30 members elected by universal suffrage in five geographic districts and 30 members selected by 28 “functional constituencies” representing various important sectors. -

OFFICIAL RECORD of PROCEEDINGS Wednesday, 28

LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL ─ 28 May 2003 6877 OFFICIAL RECORD OF PROCEEDINGS Wednesday, 28 May 2003 The Council met at half-past Two o'clock MEMBERS PRESENT: THE PRESIDENT THE HONOURABLE MRS RITA FAN HSU LAI-TAI, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE KENNETH TING WOO-SHOU, J.P. THE HONOURABLE JAMES TIEN PEI-CHUN, G.B.S., J.P. DR THE HONOURABLE DAVID CHU YU-LIN, J.P. THE HONOURABLE CYD HO SAU-LAN THE HONOURABLE ALBERT HO CHUN-YAN IR DR THE HONOURABLE RAYMOND HO CHUNG-TAI, J.P. THE HONOURABLE LEE CHEUK-YAN THE HONOURABLE MARTIN LEE CHU-MING, S.C., J.P. THE HONOURABLE ERIC LI KA-CHEUNG, J.P. DR THE HONOURABLE DAVID LI KWOK-PO, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE FRED LI WAH-MING, J.P. DR THE HONOURABLE LUI MING-WAH, J.P. THE HONOURABLE NG LEUNG-SING, J.P. 6878 LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL ─ 28 May 2003 THE HONOURABLE MARGARET NG THE HONOURABLE MRS SELINA CHOW LIANG SHUK-YEE, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE JAMES TO KUN-SUN THE HONOURABLE CHEUNG MAN-KWONG THE HONOURABLE HUI CHEUNG-CHING, J.P. THE HONOURABLE CHAN KWOK-KEUNG THE HONOURABLE CHAN YUEN-HAN, J.P. THE HONOURABLE BERNARD CHAN, J.P. THE HONOURABLE CHAN KAM-LAM, J.P. THE HONOURABLE MRS SOPHIE LEUNG LAU YAU-FUN, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE LEUNG YIU-CHUNG THE HONOURABLE SIN CHUNG-KAI THE HONOURABLE ANDREW WONG WANG-FAT, J.P. DR THE HONOURABLE PHILIP WONG YU-HONG THE HONOURABLE WONG YUNG-KAN THE HONOURABLE JASPER TSANG YOK-SING, G.B.S., J.P.