National Register of Historic Places Continuation Sheet RESOURCES DIVISION

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Read This Issue

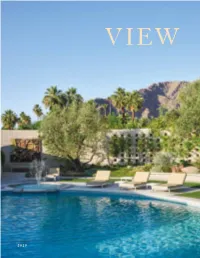

VIEW 2019 VIEW from the Director’s Office Dear Friends of LALH, This year’s VIEW reflects our recent sharpening focus on California, from the Bay Area to San Diego. We open with an article by JC Miller about Robert Royston’s final project, the Harris garden in Palm Springs, which he worked on personally and continues to develop with the owners. A forthcoming LALH book on Royston by Miller and Reuben M. Rainey, the fourth volume in our Masters of Modern Landscape Design series, will be released early next year at Modernism Week in Palm Springs. Both article and book feature new photographs by the stellar landscape photographer Millicent Harvey. Next up, Kenneth I. Helphand explores Lawrence Halprin’s extraordinary drawings and their role in his de- sign process. “I find that I think most effectively graphically,” Halprin explained, and Helphand’s look at Halprin’s prolific notebook sketches and drawings vividly illuminates the creative symbiosis that led to the built works. The California theme continues with an introduction to Paul Thiene, the German-born landscape architect who super- vised the landscape development of the 1915 Panama-California Exposition in San Diego and went on to establish a thriving practice in the Southland. Next, the renowned architect Marc Appleton writes about his own Santa Barbara garden, Villa Corbeau, inspired—as were so many of Thiene’s designs—by Italy. The influence of Italy was also major in the career of Lockwood de Forest Jr. Here, Ann de Forest remembers her grandparents and their Santa Barbara home as the family archives, recently donated by LALH, are moved to the Architecture & Design Collections at UC Santa Barbara. -

A Historic Guide to Pasadena

A HISTORIC GUIDE TO PASADENA WELCOME TO CICLAVIA—PASADENA Welcome to CicLAvia Pasadena, our first event held entirely outside of the city of Los Angeles! And we couldn’t have picked a prettier city; OUR PARTNERS bordered by the San Gabriel Mountains and the Arroyo Seco, Pasadena, which means “Crown of the Valley” in the Ojibwa/Chippewa language, has long been known for its beauty and ideal climate. After all, a place best known for a parade of flower-covered floats— OUR SUPPORTERS OUR SPONSORS City of Los Angeles Cirque du Soleil the world-famous Tournament of Roses since Annenberg Foundation Tern Bicycles Ralph M. Parsons Foundation The Laemmle Charitable Foundation 1890—can’t be bad, right? Rosenthal Family Foundation Los Angeles County Bicycle Coalition David Bohnett Foundation Indie Printing Today’s route centers on Colorado Boulevard— Wahoo’s Fish Taco OUR MEDIA PARTNERS Walden School Pasadena’s main east-west artery—a road with a The Los Angeles Times Laemmle Theatres THANKS TO long and rich history. Originally called Colorado 89.3 FM KPCC Public Radio La Grande Orange Café Time Out Los Angeles Old Pasadena Management District Street, the road was named to honor the latest Pasadena Star-News Pasadena Arts Council state to join the Union at the time (1876) and Pasadena Heritage Pasadena Museum of History was changed to “Boulevard” in 1958. The beau- Playhouse District Association South Lake Business Association tiful Colorado Street Bridge, which was built in 1913 and linked the San Gabriel Valley to the San Fernando Valley, still retains the old name. -

Classy City: Residential Realms of the Bay Region

Classy City: Residential Realms of the Bay Region Richard Walker Department of Geography University of California Berkeley 94720 USA On-line version Revised 2002 Previous published version: Landscape and city life: four ecologies of residence in the San Francisco Bay Area. Ecumene . 2(1), 1995, pp. 33-64. (Includes photos & maps) ANYONE MAY DOWNLOAD AND USE THIS PAPER WITH THE USUAL COURTESY OF CITATION. COPYRIGHT 2004. The residential areas occupy the largest swath of the built-up portion of cities, and therefore catch the eye of the beholder above all else. Houses, houses, everywhere. Big houses, little houses, apartment houses; sterile new tract houses, picturesque Victorian houses, snug little stucco homes; gargantuan manor houses, houses tucked into leafy hillsides, and clusters of town houses. Such residential zones establish the basic tone of urban life in the metropolis. By looking at residential landscapes around the city, one can begin to capture the character of the place and its people. We can mark out five residential landscapes in the Bay Area. The oldest is the 19th century Victorian townhouse realm. The most extensive is the vast domain of single-family homes in the suburbia of the 20th century. The grandest is the carefully hidden ostentation of the rich in their estates and manor houses. The most telling for the cultural tone of the region is a middle class suburbia of a peculiar sort: the ecotopian middle landscape. The most vital, yet neglected, realms are the hotel and apartment districts, where life spills out on the streets. More than just an assemblage of buildings and styles, the character of these urban realms reflects the occupants and their class origins, the economics and organization of home- building, and larger social purposes and planning. -

Report Draft Initial Study/Mitigated Negative Declaration 2016-10-14

Focused Environmental Impact Report SCREENCHECK DRAFT #2 Ursa Residential Development Project Appendix C Technical Memorandum – Summary Historical Resources Report Prepared for: City of Fremont AECOM September 2017 C-1 Focused Environmental Impact Report SCREENCHECK DRAFT #2 Ursa Residential Development Project This page intentionally left blank. Prepared for: City of Fremont AECOM September 2017 C-2 TECHNICAL MEMORANDUM AECOM 2020 L Street, Suite 400 Sacramento, CA 95811 Date: July 3, 2017; revised September 18, 2017 To: Bill Roth, Associate Planner, City of Fremont From: Jeremy Hollins, MA, Senior Architectural Historian, AECOM Chandra Miller, MA, Architectural Historian, AECOM Subject: Ursa Residential Development Project – Summary Historical Resources Report Introduction AECOM Technical Services, Inc. (AECOM) has been retained by the City of Fremont to complete an Initial Study and Focused EIR for the Ursa Residential Development Project (project). The project, located at 48495 Ursa Drive, is a Precise Planned Development that will construct 17 new residences and relocate one existing on-site residence on a property that has been previously determined a historical resource for purposes of the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA). Impacts to historical resources will be examined in the Focused EIR that addresses the relocation of the historical residence and the construction of the new residences. This memorandum provides additional historic context and more detailed evaluation of the property to support the findings of the Focused EIR. Proposed Project As part of the proposed Ursa Residential project, the applicant proposes rezoning a 2.67-acre site from R‐1‐6 to a Planned District; the relocation of the existing historic-period residence and ancillary tankhouse; demolition of other existing structures (barn, garage, and various sheds) on-site; and construction of 17 new single family houses. -

Draft Environmental Impact Report for the University of California, Santa

Appendix E Cultural Resources Information Appendix E1 – Archaeological Resources Report Bay Area Division Phone: 510.524.3991 900 Modoc Street Fax: 510.524.4419 Berkeley, CA 94707 www.pacificlegacy.com Date: July 3, 2020 To: Claudia Garcia, Ascent Environmental. From: John Holson Subject: Technical Memo For Cultural Resource Studies, UC Santa Cruz, Long Range Development Plan. Pacific Legacy has prepared this memo to assist Ascent Environmental in preparing the Cultural Resources Section of the UC Santa Cruz, Long Range Development Plan (LRDP) Environmental Impact Report. Below are our findings and sections for the LRDP. ENVIRONMENTAL SETTING Regional Prehistory The earliest confirmed evidence of prehistoric occupation in the Santa Cruz region comes from an archaeological site (CA-SCR-177) located 4 miles northeast of the campus in the Santa Cruz Mountains near Scotts Valley. Cartier (1993) postulated that CA-SCR-177 may date to approximately 10,000 years before present (BP). This is supported by the California Central Coast Chronology (Jones et al. 2007), which posits prehistoric life in the region extending to 10,000 years BP or earlier. While few sites have been identified from the Paleoindian through the Early Archaic (8000 to 5000 BP) periods in the Santa Cruz area, numerous sites have been dated to the Middle Archaic (5000 BP to 3000 BP) and Late Archaic (3000 BP to 1000 AD) periods. The Late Prehistoric Period (1000 to about 1600 AD) has been identified from at least one site near Santa Cruz (Fitzgerald and Ruby 1997; Hylkema 1991). Archaeological evidence indicates that Native groups in the region participated in extensive trade networks. -

Making a Place for Art

JC Miller MAKING A PLACE FOR ART: COLLABORATION BETWEEN EDITH HEATH AND ROBERT ROYSTON Edith Heath seated near the garden room, Heath Collection, EDA, UCB. 215 The years following World War II saw extraordinary growth in California. Philosophies Heath: Edith So began a collaboration that generated a remarkable garden that The home front effort brought industrial production to California coastal cities reflected both Royston’s modernist design principles and Heath’s creative on an unprecedented scale. This was especially true in the San Francisco Bay talents. Beyond the Heath’s garden, the pair collaborated on tile art in the Area. Thousands moved to the Golden State to work in wartime industries landscape and on furniture design. Perhaps as a result of their friendship and and returning veterans further swelled the numbers as they chose to stay after shared approach to design, Royston specified tile made by Heath for all the discharge from military service at the ports of Oakland and San Francisco.1 gardens he designed throughout his long career.3 This postwar boom was nourished by an increase in high-paying jobs in the commercial, manufacturing, and professional sectors, a home-building boom Robert Royston, Landscape Architect fueled by mortgages secured by the Federal Housing Administration and educational opportunities funded by the G.I. Bill of Rights. In Robert Royston, Heath found a kindred creative spirit whose work as a Many of the state’s new residents were creatives: architects, designers, landscape architect was becoming well known in California and nationally. artists, and performers drawn by the region’s vitality. -

Charles Luckman Papers, 1908-2000

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8057gjv No online items Charles Luckman Papers, 1908-2000 Clay Stalls William H. Hannon Library Loyola Marymount University One LMU Drive, MS 8200 Los Angeles, CA 90045-8200 Phone: (310) 338-5710 Fax: (310) 338-5895 Email: [email protected] URL: http://library.lmu.edu/ © 2012 Loyola Marymount University. All rights reserved. Charles Luckman Papers, CSLA-34 1 1908-2000 Charles Luckman Papers, 1908-2000 Collection number: CSLA-34 William H. Hannon Library Loyola Marymount University Los Angeles, California Processed by: Clay Stalls Date Completed: 2008 Encoded by: Clay Stalls © 2012 Loyola Marymount University. All rights reserved. Descriptive Summary Title: Charles Luckman papers Dates: 1908-2000 Collection number: CSLA-34 Creator: Luckman, Charles Collection Size: 101 archival document boxes; 16 oversize boxes; 2 unboxed scrapbooks, 2 flat files Repository: Loyola Marymount University. Library. Department of Archives and Special Collections. Los Angeles, California 90045-2659 Abstract: This collection consists of the personal papers of the architect and business leader Charles Luckman (1909-1999). Luckman was president of Pepsodent and Lever Brothers in the 1940s. In the 1950s, with William Pereira, he resumed his architectural career. Luckman eventually developed his own nationally-known firm, responsible for such buildings as the Boston Prudential Center, the Fabulous Forum in Los Angeles, and New York's Madison Square Garden. Languages: Languages represented in the collection: English Access Collection is open to research under the terms of use of the Department of Archives and Special Collections, Loyola Marymount University. Publication Rights Materials in the Department of Archives and Special Collections may be subject to copyright. -

University of California Santa Cruz

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA SANTA CRUZ PRECARIOUS CITY: MARGINAL WORKERS, THE STATE, AND WORKING-CLASS ACTIVISM IN POST-INDUSTRIAL SAN FRANCISCO, 1964-1979 A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in HISTORY by Laura Renata Martin March 2014 The dissertation of Laura Renata Martin is approved: ------------------------------------------------------- Professor Dana Frank, chair ------------------------------------------------------- Professor David Brundage ------------------------------------------------------- Professor Alice Yang ------------------------------------------------------- Professor Eileen Boris ------------------------------------------------------- Tyrus Miller, Vice Provost and Dean of Graduate Studies Table of Contents Introduction. 1 Chapter One. The War Over the War on Poverty: Civil Rights Groups, the War on Poverty, and the “Democratization” of the Great Society 53 Chapter Two. Crisis of Social Reproduction: Organizing Around Public Housing and Welfare Rights 107 Chapter Three. Policing and Black Power: The Hunters Point Riot, The San Francisco Police Department, and The Black Panther Party 171 Chapter Four. Labor Against the Working Class: The International Longshore Workers’ Union, Organized Labor, and Downtown Redevelopment 236 Chapter Five. Contesting Sexual Labor in the Post-Industrial City: Prostitution, Policing, and Sex Worker Organizing in the Tenderloin 296 Conclusion. 364 Bibliography. 372 iii Abstract Precarious City: Marginal Workers, the State, and Working-Class Activism in Post- Industrial San Francisco, 1964-1979 Laura Renata Martin This project investigates the effects of San Francisco’s transition from an industrial to a post-industrial economy on the city’s social movements between 1964 and 1979. I re-contextualize the city’s Black freedom, feminist, and gay and transgender liberation movements as struggles over the changing nature of urban working-class life and labor in the postwar period. -

Westchester-Playa Del

Historical Timeline of the WESTCHESTER-PLAYA DEL REY 1928 1948 Mines Field begins operation 1940 Loyola Theater built, Events Significant to Local Development (eventually becoming LAX) 1925 1929 Hughes Aircraft and Westchester 1834 1902 Waste treatment Oil discovered in the manufacturing plant opens High School opens Centinela Adobe The Beach Land Company Indigenous Gabrielino / Early 1800s facility first opens area, production grows constructed (now the purchases and begins subdividing Tongva people have Spanish land grants at Hyperion in the following decades oldest remaining over 1000 acres in Playa del Rey. inhabited the region for divide the area into Treatment Plant building in the area) Trolley from Los Angeles to the thousands of years ranchos, including: site 1938 1941. UNLV Library Special Collections Rancho La Ballona, beach opens, bringing visitors to Rancho Sausal Redondo, and the new resort. Ballona Creek channelized by Army Rancho Aguaje de Centinela LAX Early History, www.lawa.org 1938. Marina Del Rey Historical Society Corps of Engineers to control flooding 1929 1982. Jack Lardomita for the Loyola University moves Daily Breeze Historical Society of Centinela Valley 1941-46 to Westchester Planned 1946 Replica of a Tongva ki located in Franklin Canyon Park. 1886-89 Jengod via Wikimedia Commons community of Dredging to create Commercial 10,000 people airline ‘Port Ballona’ Kirk Crawford, via Wikimedia Commons developed in service begins, stalls, and is c1938. Marina Del Rey Historical Society Westchester abandoned Mishigaki at English Wikipedia begins at for defense LAX 1919. California Historical Society Collection, University of Southern California workers November 9, 1902, p. IV-6. Los Angeles Times 1700 1800 1850 1900 1910 1920 1930 1940 1932 1926 LA hosts Olympic Los Angeles City Hall 1781 Games. -

Thomas D. Church Collection, 1933-1977

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/tf938nb4jf Online items available Thomas D. Church Collection, 1933-1977 Processed by the Environmental Design Archives staff Environmental Design Archives College of Environmental Design 230 Wurster Hall #1820 University of California, Berkeley Berkeley, California, 94720-1820 Phone: (510) 642-5124 Fax: (510) 642-2824 Email: [email protected] http://www.ced.berkeley.edu/cedarchives/ © 1999 The Regents of California. All rights reserved. Note Arts and Humanities--ArchitectureHistory--California History--Bay Area HistoryHistory--California HistoryGeographical (By Place)--CaliforniaGeographical (By Place)--California--Bay AreaGeographical (By Place)--University of California--UC BerkeleyGeographical (By Place)--University of California--UC Santa CruzHistory--University of California History--UC Berkeley HistoryHistory--University of California History--UC Santa Cruz History Thomas D. Church Collection, 1997-1 1 1933-1977 Thomas D. Church Collection, 1933-1977 Collection Number: 1997-1 Environmental Design Archives University of California, Berkeley Berkeley, California Contact Information: Environmental Design Archives College of Environmental Design 230 Wurster Hall #1820 University of California, Berkeley Berkeley, California, 94720-1820 Phone: (510) 642-5124 Fax: (510) 642-2824 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.ced.berkeley.edu/cedarchives/ Processed by: Environmental Design Archives staff Date Completed: January 1999 Encoded by: Campbell J. Crabtree Funding: Arrangement and description of this collection was funded by the Department of Landscape Architecture and Environmental Planning and by a grant from the Getty Foundation. © 1999 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Descriptive Summary Collection Title: Thomas D. Church Collection, Date (inclusive): 1933-1977 Collection Number: 1997-1 Creator: Church, Thomas Dolliver, 1902-1978 Extent: 114 boxes, 9 flat boxes, 29 tubes, 8 flat file drawers Repository: Environmental Design Archives. -

National Register of Historic Places Registration Form

NPS Form 10-900 OMB No_1024-0018 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This fonn is for use in nominating or requesting detenninations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in National Register Bulletin, How lo Complele /he Nalional Register of Historic Places Regislralion Form. If any item does not 1\PPJY .to..tbe property being documented, enter "N/N for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas f sig¢(ECE I V'!:V~80 ~·~~~s;~;~::;;;"'"'''"" \ AUG- 8 2014 Other names/site number: \:lAT.REE: STEROF HlSTOOlGPLACES Name of related multiple property listing: _ r~·~IQ~LPAR !< SEI1Y ICE NIA (Enter "N/ A" if property is not part of a multiple property listing 2. Location Street & number: 3900 Manchester Boulevard City or town: Inglewood State: _..C=A=-==~-- County: Los Angeles Not For Publication: D Vicinity: D 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this _x_ nomination _ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property _x__ meets _does not meet the National Register Criteria. I recommend that this property be considered significant at the following level(s) of significance: national _statewide ..,X_ local Applicable National Register Criteria: _A _B _x_c D Jenan Saunders, Deputy State Historic Preservation Officer Date California State Office of Historic Preservation State or Federal agency/bureau or Tribal Government In my opinion, the property ·- meets _ does not meet the National Register criteria. -

Resilient Los Angeles

Introduction MARCH 2018 RESILIENT LOS ANGELES LOS RESILIENT RESILIENT LOS ANGELES lamayor.org/resilience RESILIENT LOS ANGELES Introduction 4 CHAPTERS, 15 GOALS, 96 ACTIONS CHAPTER 1 GOAL 1: Educate and engage Angelenos around risk pg 31 reduction and preparedness so they can be SAFE AND THRIVING ANGELENOS Resilient Los Angeles is a call to action for every Angeleno to contribute will call attention to the role that individuals, self-sufficient for at least seven to 14 days to the resilience of our city at every scale. families, businesses, and property owners after a major shock. can take to both prevent and prepare for GOAL 2: Develop additional pathways to employment pg 41 future shocks and stresses. and the delivery of financial literacy tools to support our most vulnerable Angelenos. GOAL 3: Cultivate leadership, stewardship, and pg 46 equity with young Angelenos. CHAPTER 2 GOAL 4: Build social cohesion and increase pg 56 STRONG AND CONNECTED preparedness through community collaboration. NEIGHBORHOODS will focus on actions that support and strengthen community GOAL 5: Increase programs and partnerships that pg 65 connectedness and collaboration. foster welcoming neighborhoods. GOAL 6: Prepare and protect those most vulnerable pg 69 to increasing extreme heat. GOAL 7: Reduce health and wellness disparities pg 76 across neighborhoods. CHAPTER 3 GOAL 8: Integrate resilience principles into pg 86 government to prioritize our most PREPARED AND RESPONSIVE CITY will emphasize strategies the City and vulnerable people, places, and systems. its partners will take to ensure that GOAL 9: Equip government with technology and pg 95 Los Angeles is equipped to address current data to increase situational awareness and future challenges.