From Mow Cop to Airedale Street by D

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![Schedule 14.1 Schedule of Historic Heritage [Rcp/Dp]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2664/schedule-14-1-schedule-of-historic-heritage-rcp-dp-142664.webp)

Schedule 14.1 Schedule of Historic Heritage [Rcp/Dp]

Schedule 14.1 Schedule of Historic Heritage [rcp/dp] Introduction The criteria in B5.2.2(1) to (5) have been used to determine the significant historic heritage places in this schedule and will be used to assess any proposed additions to it. The criteria that contribute to the heritage values of scheduled historic heritage in Schedule 14.1 are referenced with the following letters: A: historical B: social C: Mana Whenua D: knowledge E: technology F: physical attributes G: aesthetic H: context. Information relating to Schedule 14.1 Schedule 14.1 includes for each scheduled historic heritage place; • an identification reference (also shown on the Plan maps) • a description of a scheduled place • a verified location and legal description and the following information: Reference to Archaeological Site Recording Schedule 14.1 includes in the place name or description a reference to the site number in the New Zealand Archaeological Association Site Recording Scheme for some places, for example R10_709. Categories of scheduled historic heritage places Schedule 14.1 identifies the category of significance for historic heritage places, namely: (a) outstanding significance well beyond their immediate environs (Category A); or (b) the most significant scheduled historic heritage places scheduled in previous district plans where the total or substantial demolition or destruction was a discretionary or non-complying activity, rather than a prohibited activity (Category A*). This is an interim category until a comprehensive re-evaluation of these places is undertaken and their category status is addressed through a plan change process; or 1 (c) considerable significance to a locality or greater geographic area (Category B). -

Old Heath Hayes' Have Been Loaned 1'Rom Many Aources Private Collections, Treasured Albums and Local Authority Archives

OLD HEATH HAVES STAFFORDSHIRE COUNTY COUNCIL. EDUCATION DEPARTMENT, LOCAL HISTORY SOURCE BOOK L.50 OLD HEATH HAVES BY J.B. BUCKNALL AND J,R, FRANCIS MARQU£SS OF' ANGl.ESEV. LORO OF' THE MAtt0R OF HEATH HAVES STAFFORDSHIRE COUNTY COUNCIL, EDUCATION DEPAR TMENT. IN APPRECIATION It is with regret that this booklet will be the last venture produced by the Staffordshire Authority under the inspiration and guidance of Mr. R.A. Lewis, as historical resource material for schools. Publi cation of the volume coincides with the retirement of Roy Lewis, a former Headteacher of Lydney School, Gloucestershire, after some 21 years of service in the Authority as County Inspector for History. When it was first known that he was thinking of a cessation of his Staffordshire duties, a quick count was made of our piles of his 'source books' . Our stock of his well known 'Green Books' (Local History Source Books) and 'Blue Books' (Teachers Guides and Study Books) totalled, amazingly, just over 100 volumes, ·a mountain of his torical source material ' made available for use within our schools - a notable achievement. Stimulating, authoritative and challenging, they have outlined our local historical heritage in clear and concise form, and have brought the local history of Staffordshire to the prominence that it justly deserves. These volumes have either been written by him or employed the willing ly volunteered services of Staffordshire teachers. Whatever the agency behind the pen it is obvious that forward planning, correlation of text and pictorial aspects, financial considerations for production runs, organisation of print-run time with a busy print room, distri bution of booklets throughout Staffordshire schools etc. -

SALES TRACK RECORD City Metro Team April 2018 Sales Track Record

SALES TRACK RECORD City MEtro Team April 2018 sales track record 777-779 NEW NORTH ROAD, MT ALBERT 31 MACKELVIE STREET, GREY LYNN 532-536 PARNELL ROAD, PARNELL PRICE: $1,300,000 PRICE: $2,715,000 PRICE: $13,600,000 METHOD: Tender METHOD: Deadline Private Treaty METHOD: Tender ANALYSIS: Part Vacant, $7,103/m² land & buildings ANALYSIS: $5,645/m² on land ANALYSIS: $7,039/m² land area BROKERS: Reese Barragar BROKERS: Reese Barragar, Murray Tomlinson BROKERS: Andrew Clark, Graeme McHoull, Cam Paterson DATE: March 2018 DATE: March 2018 DATE: March 2018 VENDOR: St Albans Limited VENDOR: Telecca New Zealand Limited VENDOR: Empire Trust (Mike & Irene Rosser) sales track record 35 CHURCH STREET, ONEHUNGA 57L LIVINGSTONE STREET, GREY LYNN 62 BROWN STREET, ONEHUNGA PRICE: $1,210,000 PRICE: $515,000 PRICE: $2,700,000 METHOD: Auction METHOD: Deadline Private Treaty METHOD: Auction ANALYSIS: $4,115/m² land & building ANALYSIS: Vacant, $8,583/m2 Land & Buildings ANALYSIS: 4.62% yield BROKERS: Murry Tomlinson BROKERS: Reese Barragar, Shaydon Young BROKERS: Murry Tomlinson, Reese Barragar DATE: March 2018 DATE: March 2018 DATE: March 2018 VENDOR: Walker Trust VENDOR: Lion Rock Roast Limited VENDOR: Shanks & Holmes sales track record 69/210-218 VICTORIA STREET WEST, VICTORIA QUARTER 10 ADELAIDE STREET, VICTORIA QUARTER 60 MT EDEN ROAD, MT EDEN PRICE: $1,300,000 PRICE: $855,000 PRICE: $2,600,000 METHOD: Private Treaty METHOD: Deadline Private Treaty METHOD: Tender ANALYSIS: Vacant, $6,075/m2 land & buildings ANALYSIS: Vacant, $8,066/m² land & building ANALYSIS: -

Proceedings Wesley Historical Society

Proceedings OF THE Wesley Historical Society Editor: REV. JOHN c. BOWMER, M.A., B.O. Volume XXXIV December 1963 CHURCH METHODISTS IN IRELAND R. OLIVER BECKERLEGGE'S interesting contribution on the Church Methodists (Proceedings, xxxiv, p. 63) draws D attention to the fact that the relationship of Methodists with the Established Church followed quite a different pattern in Ireland. Had it not been so, there would have been no Primitive Wesleyan Methodist preacher to bring over to address a meeting in Beverley, as mentioned in that article. Division in Methodism in Ireland away from the parent Wesleyan body was for the purpose of keeping in closer relation with-and not to move further away from-the Established (Anglican) Church of Ireland. Thus, until less than ninety years ago, there was still a Methodist connexion made up of members of the Anglican Church. In Ireland, outside the north-eastern region where Presbyterian ism predominates, tensions between the Roman Catholic and Protestant communities made it seem a grievous wrong to break with the Established Church. In the seventeenth century, the Independent Cromwellian settlers very soon threw in their lot with that Church, which thereby has had a greate~ Protestant Puritan element than other branches of Anglicanism. Even though early Methodism in Ireland showed the same anomalous position regard ing sacraments and Church polity generally, the sort of solution provided in England by the Plan of Pacification was not adopted until 1816, over twenty years later. Those who disagreed were not able to have the decision reversed at the 1817 Irish Conference. Meeting at Clones, they had formed a committee to demand that no Methodist preacher as such should administer the sacraments, and then in 1818, at a conference in Dublin, they established the Primitive Wesleyan Methodist Connexion. -

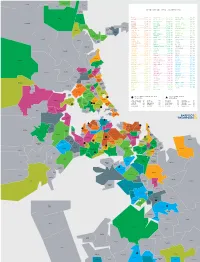

TOP MEDIAN SALE PRICE (OCT19—SEP20) Hatfields Beach

Warkworth Makarau Waiwera Puhoi TOP MEDIAN SALE PRICE (OCT19—SEP20) Hatfields Beach Wainui EPSOM .............. $1,791,000 HILLSBOROUGH ....... $1,100,000 WATTLE DOWNS ......... $856,750 Orewa PONSONBY ........... $1,775,000 ONE TREE HILL ...... $1,100,000 WARKWORTH ............ $852,500 REMUERA ............ $1,730,000 BLOCKHOUSE BAY ..... $1,097,250 BAYVIEW .............. $850,000 Kaukapakapa GLENDOWIE .......... $1,700,000 GLEN INNES ......... $1,082,500 TE ATATŪ SOUTH ....... $850,000 WESTMERE ........... $1,700,000 EAST TĀMAKI ........ $1,080,000 UNSWORTH HEIGHTS ..... $850,000 Red Beach Army Bay PINEHILL ........... $1,694,000 LYNFIELD ........... $1,050,000 TITIRANGI ............ $843,000 KOHIMARAMA ......... $1,645,500 OREWA .............. $1,050,000 MOUNT WELLINGTON ..... $830,000 Tindalls Silverdale Beach SAINT HELIERS ...... $1,640,000 BIRKENHEAD ......... $1,045,500 HENDERSON ............ $828,000 Gulf Harbour DEVONPORT .......... $1,575,000 WAINUI ............. $1,030,000 BIRKDALE ............. $823,694 Matakatia GREY LYNN .......... $1,492,000 MOUNT ROSKILL ...... $1,015,000 STANMORE BAY ......... $817,500 Stanmore Bay MISSION BAY ........ $1,455,000 PAKURANGA .......... $1,010,000 PAPATOETOE ........... $815,000 Manly SCHNAPPER ROCK ..... $1,453,100 TORBAY ............. $1,001,000 MASSEY ............... $795,000 Waitoki Wade HAURAKI ............ $1,450,000 BOTANY DOWNS ....... $1,000,000 CONIFER GROVE ........ $783,500 Stillwater Heads Arkles MAIRANGI BAY ....... $1,450,000 KARAKA ............. $1,000,000 ALBANY ............... $782,000 Bay POINT CHEVALIER .... $1,450,000 OTEHA .............. $1,000,000 GLENDENE ............. $780,000 GREENLANE .......... $1,429,000 ONEHUNGA ............. $999,000 NEW LYNN ............. $780,000 Okura Bush GREENHITHE ......... $1,425,000 PAKURANGA HEIGHTS .... $985,350 TAKANINI ............. $780,000 SANDRINGHAM ........ $1,385,000 HELENSVILLE .......... $985,000 GULF HARBOUR ......... $778,000 TAKAPUNA ........... $1,356,000 SUNNYNOOK ............ $978,000 MĀNGERE ............. -

General Index

Wesley Historical Society GENERAL INDEX TO THE "PROCEEDINGS" VOLS. I - XXX AND PUBLICATIONS I - IV (1897-1956) Compiled by JOHN A. VICKERS, B.A. PR.IN1ED FOR. THE WESLEY HISTOR.ICAL SOCIETY by ALFRED A. T ABERER 295. WELFORD ROAD, LEICESTER 19 60 CONTENTS Introductory Note IV Abbreviations VI General Index Letters of John Wesley 45 Index to Illustrations 49 Index to Contributors 53 INTRODUCTORY NOTE HIS general Index to the Society's Proceedings Volumes I-XXX and Publications Nos. I-IV has occupied the leisure hours of Tthe past five years. Begun on a much more limited scale in response to a· passing remark by the Editor in Volume XXXI, p. 106, it has since been revised, at the request of the Society's Executive Committee, to make it as comprehensive as the limit ations of the compiler and the hard economics of publication allow. It is an entirely new index, the fruit of three successive journeys through the Proceedings; not an amalgam of the indexes to the sep arate volumes (though it has been carefully checked against many of these in the closing stages of the work). It has also been checked against L. T. Daw's "Skeleton" Index to Volumes I-XVI, which it therefore supersedes. A very large proportion of the references given in the volume indexes are too incidental to be of any value: the unconvinced reader is invited to confirm this the hard way. I have attempted both to exclude incidental references which would merely waste the time and patience of the user, and at the same time to include all references, however incidental, which may at some time be of use. -

Geocene-24.Pdf

Geocene Auckland GeoClub Magazine Number 24, December 2020 Editor: Jill Kenny CONTENTS Instructions on use of hyperlinks last page 19 NEW 14C RESULT CONFIRMS 28,000 YEAR OLD Elaine R. Smid, 2 – 5 MAUNGAWHAU / MT EDEN ERUPTION AGE Bruce W. Hayward, Thomas Stolberger, Roderick Wallace, Ewart Barnsley FORTY-SEVEN YEARS OF EROSION AND WEATHERING Bruce W. Hayward 6 – 7 OF LION ROCK BOMB, PIHA MAORI BAY MICROMINERALS Tim Saunderson 8 – 14 PROXY EVIDENCE FROM TAMAKI DRIVE FOR THE Bruce W. Hayward 15 – 16 LOCATION OF SUBMERGED STREAM VALLEYS BENEATH HOBSON BAY, AUCKLAND CITY THE FIRST EXPLANATION IS NOT ALWAYS THE BEST Bruce W. Hayward 17 – 18 Corresponding authors’ contact information 19 Geocene is a periodic publication of Auckland Geology Club, a section of the Geoscience Society of New Zealand’s Auckland Branch. Contributions about the geology of New Zealand (particularly northern New Zealand) from members are welcome. Articles are lightly edited but not refereed. Please contact Jill Kenny [email protected] 1 NEW 14C RESULT CONFIRMS 28,000 YEAR OLD MAUNGAWHAU / MT EDEN ERUPTION AGE Elaine R Smid1, Bruce W Hayward2, Thomas Stolberger1, Roderick Wallace1, and Ewart Barnsley3 1 The University of Auckland 2 Geomarine Research 3 City Rail Link In February 2019, City Rail Link (CRL) reported that their The large obstruction (>1 m diameter in a 2 m drill hole) micro-tunnel boring machine “Jeffie” became entangled caused Jeffie to veer off course. CRL removed the wood in a large tree at 15 m depth, approximately 50 m north fragments and pulled them to the surface (Fig. -

The Demographic Transformation of Inner City Auckland

New Zealand Population Review, 35:55-74. Copyright © 2009 Population Association of New Zealand The Demographic Transformation of Inner City Auckland WARDLOW FRIESEN * Abstract The inner city of Auckland, comprising the inner suburbs and the Central Business District (CBD) has undergone a process of reurbanisation in recent years. Following suburbanisation, redevelopment and motorway construction after World War II, the population of the inner city declined significantly. From the 1970s onwards some inner city suburbs started to become gentrified and while this did not result in much population increase, it did change the characteristics of inner city populations. However, global and local forces converged in the 1990s to trigger a rapid repopulation of the CBD through the development of apartments, resulting in a great increase in population numbers and in new populations of local and international students as well as central city workers and others. he transformation of Central Auckland since the mid-twentieth century has taken a number of forms. The suburbs encircling the TCentral Business District (CBD) have seen overall population decline resulting from suburbanisation, as well as changing demographic and ethnic characteristics resulting from a range of factors, and some areas have been transformed into desirable, even elite, neighbourhoods. Towards the end of the twentieth century and into the twenty first century, a related but distinctive transformation has taken place in the CBD, with the rapid construction of commercial and residential buildings and a residential population growth rate of 1000 percent over a fifteen year period. While there are a number of local government and real estate reports on this phenomenon, there has been relatively little academic attention to its nature * School of Environment, The University of Auckland. -

DSO 12D Stoke on Trent DA

Digital Switchover (DSO) Programme Radio DSO Block 12D Stoke-on-Trent Document Reference: Radio DSO Stoke-on-Trent–2.0 Release Date: 02 June 2011 Company Confidential © Copyright – Arqiva Limited, 2011 The information that is contained in this document is the property of Arqiva Limited. The contents of the document must not be reproduced or disclosed wholly or in part or used for purposes other than that for which it is supplied without the prior written permission of Arqiva Limited. Document template: c:\templates\dsot_0102_v4-1.dot Radio DSO Block 12D Stoke-on-Trent Radio DSO Stoke-on-Trent–2.0 Released: 02 June 2011 Document Details General Detail Abstract Radio DSO plan and details of the Stoke-on-Trent local multiplex on Block 12D Author Denis Ripley Verifier Brian Tait Owner Glenn Doel Optional Information Author Defined Reference No Not used Project No 951225 Cross Reference Document History Ver Date Amendment 1.0 08/04/11 Draft version for review. 1.0 18/04/11 Initial release 2.0 25/05/11 Editorial Area changes Radio DSO project UNCONTROLLED COPY ONCE PRINTED Page 2 of 21 © Copyright – Arqiva Limited, 2011 Company Confidential Radio DSO Block 12D Stoke-on-Trent Radio DSO Stoke-on-Trent–2.0 Released: 02 June 2011 Table of Contents 1 Stoke-on-Trent (12D) DSO Narrative ................................................................4 1.1 Incoming interference and sensitivity to other co-block multiplexes .....................8 1.2 Outgoing interference to other co-block multiplexes ............................................8 2 Coverage of the Multiplex ...............................................................................10 2.1 Coverage Maps ................................................................................................. 10 2.2 Population Coverage tables within Editorial Area.............................................. -

Parking Changes for Eden Terrace

Your feedback on: Parking changes for Eden Terrace November 2020 – Report on Public Feedback – Parking Changes for Eden Terrace Contents 1. Summary .......................................................................................................................................... 3 Overview ...........................................................................................................................................................3 Q1: What do submitters think about proposal? ..............................................................................................3 Q2: Top 10 feedback themes ............................................................................................................................4 Q3: Top 10 feedback themes ............................................................................................................................5 Project decisions ...............................................................................................................................................6 Next steps .........................................................................................................................................................6 2. Background ...................................................................................................................................... 7 What did we seek feedback on?.......................................................................................................................7 Why did we propose these parking -

Proceedings Wesley Historical Society

Proceedings OF THE Wesley Historical Society Editor: REv. WESLEY F. SWIFT Volume XXVIII September 1952 EDITORIAL VERY member of the Wesley Historical Society will wish to congratulate our Secretary, the Rev. Frank Baker, who has Ebeen awarded the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by the University of Nottingham for a thesis entitled: "The Rev. William Grimshaw (1708-1763) and the eighteenth-century revival of religion in England ". Dr. Baker's friends never cease to marvel at his capacity for meticulous and sustained research, his mastery of detail, and the wide range of his interests, though they often wish that in his eagerness to crowd his days he would not so fre quently burn the candle at both ends. He is a tower of strength to our Society., and his learning as well as the contents of his numerous filing cabinets are always at the disposal of any inquiring student. We have been privileged to read in typescript the thesis on Grim shaw of Haworth. It is a massive work on an important subject, and will never be superseded for the simple reason that every possible scrap of information, direct and indirect, has been care fully gathered and woven into the theme. We are glad to know that the work is being prepared for publication, and meanwhile we rejoice in Dr. Frank Baker's new distinction and the reflected glory which has thereby come to our Society . • • • • We did not know that there existed a Swedish Methodist His torical Society until a letter recently arrived from its Secretary, the Rev. Vilh. -

Memorials of Old Staffordshire, Beresford, W

M emorials o f the C ounties of E ngland General Editor: R e v . P. H. D i t c h f i e l d , M.A., F.S.A., F.R.S.L., F.R.Hist.S. M em orials of O ld S taffordshire B e r e s f o r d D a l e . M em orials o f O ld Staffordshire EDITED BY REV. W. BERESFORD, R.D. AU THOft OF A History of the Diocese of Lichfield A History of the Manor of Beresford, &c. , E d i t o r o f North's .Church Bells of England, &■V. One of the Editorial Committee of the William Salt Archaeological Society, &c. Y v, * W ith many Illustrations LONDON GEORGE ALLEN & SONS, 44 & 45 RATHBONE PLACE, W. 1909 [All Rights Reserved] T O T H E RIGHT REVEREND THE HONOURABLE AUGUSTUS LEGGE, D.D. LORD BISHOP OF LICHFIELD THESE MEMORIALS OF HIS NATIVE COUNTY ARE BY PERMISSION DEDICATED PREFACE H ILST not professing to be a complete survey of Staffordshire this volume, we hope, will W afford Memorials both of some interesting people and of some venerable and distinctive institutions; and as most of its contributors are either genealogically linked with those persons or are officially connected with the institutions, the book ought to give forth some gleams of light which have not previously been made public. Staffordshire is supposed to have but little actual history. It has even been called the playground of great people who lived elsewhere. But this reproach will not bear investigation.