Waterfowl Production for Food Security Vol

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Homestead Poultry Feed Brochure

PREMIUM QUALITY NUTRITION ® Mankato, MN 56001 www.HomesteadPoultryFeed.com www.facebook.com/homesteadpoultryfeeds W5191 Formulated to Produce Top-Quality Birds DUCKS & GEESE Waterfowl need somewhat less heat than chickens. In their rst week of life, their environment should be heated to 90º F. This temperature can be lowered in ve-degree increments each week until their fth week, after which they are usually ready to live without supplemental heat. Bedding Do not use wood shavings for birds less than two weeks old, as they are more likely to consume the shavings and get blocked up. Try to avoid using slick surfaces like newspapers; if you must use them, spread paper towels over the newspapers for the rst few days. Since they are so unsteady at rst, goslings are prone to a condition called splay-leg, or spraddle legs, so it is important for them to have good footing immediately after hatching. During warm weather, spending some time walking on grass each day can be very good for their legs — plus, they'll begin eating grass. Water A constant supply of fresh water is necessary for ducklings and goslings. For the rst week, a chick waterer works well. After that, however, they are too large to submerge their heads and clean their faces in the water, which all waterfowl must be able to do. ® Avoid using a bowl of water. Here’s why: First, ducklings and goslings may walk in their drinking water and/or leave droppings in it. Second, if they stay wet, they may catch a fatal cold. Provide a waterer that is deep enough for older ducklings and goslings Homestead Poultry Feeds to submerge their heads in but not deep enough for them to get inside or tip over. -

Incubating and Hatching Eggs

EPS-001 7/13 Incubating and Hatching Eggs Gregory S. Archer and A. Lee Cartwright* hether eggs come from a common chicken Factors that affect hatchability or an exotic bird, you must store and incu- W Breeder Hatchery bate them carefully for a successful hatch. Envi- Breeder nutrition Sanitation ronmental conditions, handling, sanitation, and Disease Egg storage record keeping are all important factors when it Mating activity Egg damage comes to incubating and hatching eggs. Egg damage Incubation—Management of Correct male and female setters and hatchers Fertile egg quality body weight Chick handling A fertile egg is alive; each egg contains living cells Egg sanitation that can become a viable embryo and then a chick. Egg storage Eggs are fragile and a successful hatch begins with undamaged eggs that are fresh, clean, and fertile. Collecting and storing fertile eggs You can produce fertile eggs yourself or obtain Fertile eggs must be collected carefully and stored them elsewhere. While commercial hatcheries properly until they are incubated. Keeping the produce quality eggs that are highly fertile, many eggs at proper storage temperatures keeps the do not ship small quantities. If you mail order embryo from starting and stopping development, eggs, be sure to pick them up promptly from your which increases embryo mortality. Collecting receiving area. Hatchability will decrease if eggs eggs frequently and storing them properly delays are handled poorly or get too hot or too cold in embryo development until you are ready to incu- transit. bate them. If you produce the eggs on site, you must care for the breeding stock properly to ensure maximum Egg storage reminders fertility. -

Than a Meal: the Turkey in History, Myth

More Than a Meal Abigail at United Poultry Concerns’ Thanksgiving Party Saturday, November 22, 1997. Photo: Barbara Davidson, The Washington Times, 11/27/97 More Than a Meal The Turkey in History, Myth, Ritual, and Reality Karen Davis, Ph.D. Lantern Books New York A Division of Booklight Inc. Lantern Books One Union Square West, Suite 201 New York, NY 10003 Copyright © Karen Davis, Ph.D. 2001 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the written permission of Lantern Books. Printed in the United States of America Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data For Boris, who “almost got to be The real turkey inside of me.” From Boris, by Terry Kleeman and Marie Gleason Anne Shirley, 16-year-old star of “Anne of Green Gables” (RKO-Radio) on Thanksgiving Day, 1934 Photo: Underwood & Underwood, © 1988 Underwood Photo Archives, Ltd., San Francisco Table of Contents 1 Acknowledgments . .9 Introduction: Milton, Doris, and Some “Turkeys” in Recent American History . .11 1. A History of Image Problems: The Turkey as a Mock Figure of Speech and Symbol of Failure . .17 2. The Turkey By Many Other Names: Confusing Nomenclature and Species Identification Surrounding the Native American Bird . .25 3. A True Original Native of America . .33 4. Our Token of Festive Joy . .51 5. Why Do We Hate This Celebrated Bird? . .73 6. Rituals of Spectacular Humiliation: An Attempt to Make a Pathetic Situation Seem Funny . .99 7 8 More Than a Meal 7. -

Dissertation

DISSERTATION THE ROLE OF DOMESTIC DUCKS IN THE MAINTENANCE AND SPREAD OF AVIAN INFLUENZA VIRUSES IN INDONESIA Submitted by Kristy L. Pabilonia Department of Microbiology, Immunology and Pathology In partial fulfillment of the requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Colorado State University Fort Collins, Colorado Summer 2012 Doctoral Committee: Advisor: Richard Bowen Tawfik Aboellail Doreene Hyatt Anthony Knight ABSTRACT THE ROLE OF DOMESTIC DUCKS IN THE MAINTENANCE AND SPREAD OF AVIAN INFLUENZA VIRUSES IN INDONESIA Wild waterfowl and aquatic birds serve as the natural reservoir host for influenza A viruses. As the reservoir, wild waterfowl play an important role in the persistence and transmission of influenza viruses among bird populations and to other mammalian species. In many Asian countries, domestic ducks are raised for meat and egg production. Some of these domestic ducks are ranged on rice paddies or post-harvest rice fields. The ducks provide service to the rice fields by fertilizing the field with feces and aerating the field by swimming and walking through the ground cover. Additionally, the ducks serve as a form of insect control through their natural grazing behaviors. The role that domestic ducks play in the ecology of influenza viruses is poorly understood. Highly pathogenic avian influenza H5N1 virus (HPAI H5N1) originated in Guangdong Province, China in 1996, which was followed by global dissemination of the virus that began in 2003. This virus is unprecedented in geographical spread, economic consequences and public health significance. At the present time, HPAI H5N1 virus is endemic six countries, including Indonesia. Indonesia has experienced the highest incidence of human infections with HPAI H5N1 virus and one of the highest case fatality rates. -

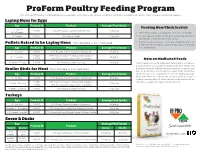

Proform Poultry Feeding Program

ProForm Poultry Feeding Program This ProForm® Poultry Feeding Program is available at Hi-Pro Feeds’ dealers in British Columbia excluding the Peace River and East Kootenay regions. Laying Hens for Eggs Age Product ID Product Average Feed Intake Feeding Hen/Chick Scratch 1st egg or 190481 18% All Purpose Laying Poultry Pellets 105 g/day 18 - 40 weeks • Hen/Chick Scratch is a mixture of corn, oats and wheat. 40+ weeks 190641 16% Laying Pellets 115 g/day • It is not a balanced diet, and birds may develop nutritional deficiencies if they are fed scratch alone. Pullets Raised to be Laying Hens (*also available in non-medicated) • Scratch can be used as a treat, but should be fed at no more than 5% of the bird’s daily diet (ex: max of 5-6 g/day Age Product ID Product Average Feed Intake for a mature hen). 0 - 6 weeks 190101 *22% Poultry Starter Crumbles (Medicated) 35 g/day 190461 18% Poultry Grower Crumbles (Medicated) or 6 - 14 weeks 65 g/day 190301 18% All Purpose Laying Poultry Crumbles Note on Medicated Feeds 14 weeks - 1st egg 190751 16% Poultry Grower Crumbles 75 g/day Poultry feeds containing medication help prevent coccidiosis, a disease which can cause lost productivity, poor health and Broiler Birds for Meat (*also available in non-medicated) mortality in your flock. Birds build immunity to coccidiosis over time so medication is not required in older birds. Medication Age Product ID Product Average Feed Intake should not be fed to laying hens that are producing eggs. Read and follow the instructions on your feed tag if you’re 0 - 21 days 190101 *22% Poultry Starter Crumbles (Medicated) 50 g/day feeding a medicated feed. -

A Molecular Phylogeny of Anseriformes Based on Mitochondrial DNA Analysis

MOLECULAR PHYLOGENETICS AND EVOLUTION Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 23 (2002) 339–356 www.academicpress.com A molecular phylogeny of anseriformes based on mitochondrial DNA analysis Carole Donne-Goussee,a Vincent Laudet,b and Catherine Haanni€ a,* a CNRS UMR 5534, Centre de Genetique Moleculaire et Cellulaire, Universite Claude Bernard Lyon 1, 16 rue Raphael Dubois, Ba^t. Mendel, 69622 Villeurbanne Cedex, France b CNRS UMR 5665, Laboratoire de Biologie Moleculaire et Cellulaire, Ecole Normale Superieure de Lyon, 45 Allee d’Italie, 69364 Lyon Cedex 07, France Received 5 June 2001; received in revised form 4 December 2001 Abstract To study the phylogenetic relationships among Anseriformes, sequences for the complete mitochondrial control region (CR) were determined from 45 waterfowl representing 24 genera, i.e., half of the existing genera. To confirm the results based on CR analysis we also analyzed representative species based on two mitochondrial protein-coding genes, cytochrome b (cytb) and NADH dehydrogenase subunit 2 (ND2). These data allowed us to construct a robust phylogeny of the Anseriformes and to compare it with existing phylogenies based on morphological or molecular data. Chauna and Dendrocygna were identified as early offshoots of the Anseriformes. All the remaining taxa fell into two clades that correspond to the two subfamilies Anatinae and Anserinae. Within Anserinae Branta and Anser cluster together, whereas Coscoroba, Cygnus, and Cereopsis form a relatively weak clade with Cygnus diverging first. Five clades are clearly recognizable among Anatinae: (i) the Anatini with Anas and Lophonetta; (ii) the Aythyini with Aythya and Netta; (iii) the Cairinini with Cairina and Aix; (iv) the Mergini with Mergus, Bucephala, Melanitta, Callonetta, So- materia, and Clangula, and (v) the Tadornini with Tadorna, Chloephaga, and Alopochen. -

Alpha Codes for 2168 Bird Species (And 113 Non-Species Taxa) in Accordance with the 62Nd AOU Supplement (2021), Sorted Taxonomically

Four-letter (English Name) and Six-letter (Scientific Name) Alpha Codes for 2168 Bird Species (and 113 Non-Species Taxa) in accordance with the 62nd AOU Supplement (2021), sorted taxonomically Prepared by Peter Pyle and David F. DeSante The Institute for Bird Populations www.birdpop.org ENGLISH NAME 4-LETTER CODE SCIENTIFIC NAME 6-LETTER CODE Highland Tinamou HITI Nothocercus bonapartei NOTBON Great Tinamou GRTI Tinamus major TINMAJ Little Tinamou LITI Crypturellus soui CRYSOU Thicket Tinamou THTI Crypturellus cinnamomeus CRYCIN Slaty-breasted Tinamou SBTI Crypturellus boucardi CRYBOU Choco Tinamou CHTI Crypturellus kerriae CRYKER White-faced Whistling-Duck WFWD Dendrocygna viduata DENVID Black-bellied Whistling-Duck BBWD Dendrocygna autumnalis DENAUT West Indian Whistling-Duck WIWD Dendrocygna arborea DENARB Fulvous Whistling-Duck FUWD Dendrocygna bicolor DENBIC Emperor Goose EMGO Anser canagicus ANSCAN Snow Goose SNGO Anser caerulescens ANSCAE + Lesser Snow Goose White-morph LSGW Anser caerulescens caerulescens ANSCCA + Lesser Snow Goose Intermediate-morph LSGI Anser caerulescens caerulescens ANSCCA + Lesser Snow Goose Blue-morph LSGB Anser caerulescens caerulescens ANSCCA + Greater Snow Goose White-morph GSGW Anser caerulescens atlantica ANSCAT + Greater Snow Goose Intermediate-morph GSGI Anser caerulescens atlantica ANSCAT + Greater Snow Goose Blue-morph GSGB Anser caerulescens atlantica ANSCAT + Snow X Ross's Goose Hybrid SRGH Anser caerulescens x rossii ANSCAR + Snow/Ross's Goose SRGO Anser caerulescens/rossii ANSCRO Ross's Goose -

Proteomic Analysis of 1-D Sarcoplasmic Protein Profiles of Pekin Duck Embryos’ Pectoralis Muscle As Influenced by Incubation Temperature

Proteomic analysis of 1-D Sarcoplasmic Protein Profiles of Pekin Duck Embryos’ Pectoralis Muscle as Influenced by Incubation Temperature THESIS Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science in the Graduate School of the Ohio State University By Yang Cheng Graduate Program in Animal Sciences The Ohio State University 2014 Master's Examination Committee: Dr. Michael Lilburn, Advisor Dr. MacDonald Wick Dr. William Pope Copyrighted by Yang Cheng 2014 Abstract The objective of this study was to identify sarcoplasmic proteins responsive to incubation temperature in Pekin duck embryos. Previous studies reported that a 1-degree Celsius increase in incubation temperature during the first 10 days can accelerate embryonic development and this study was designed to identify the effects of early incubation temperature on embryonic myogenesis. Pekin duck eggs were incubated at 37.5 ͦC or 38.5 ͦC for the first ten days and subsequently transferred to 37.5 ͦC for the rest of incubation (ED 11-28). The embryonic pectoralis muscle (PM) was collected at ED12, 18, 25 and hatch and sarcoplasmic proteins were subjected to 10% SDS-PAGE. Gels were digitized into TotalLabTM to acquire the mean band percentage (MBP) of bands. The body weight (BW) of embryos and pectoralis muscle weight (PMW) of the Pekin duck embryos were analyzed in SAS 9.3. An acceleration in BW at ED12 in the 38.5 ͦC treatment was observed but not at later ages. MIXED model is performed to determine bands responding significantly to incubation temperature. Three proteins/bands are determined to significantly respond to temperature. -

Canada Goose Control

CANADA GOOSE CONTROL LEGAL AND EFFECTIVE METHODS FOR DEALING WITH NUISANCE CANADA GEESE IN GEORGIA ABOUT THE CANADA GOOSE When sounds of their “honking” fill the air, hunters and wildlife enthusiasts look to the sky in search of Canada geese (Branta canadensis). These remarkable birds have become more common in Georgia, and in some areas they have developed into pests. The Canada goose is extremely adaptable and can live in a variety of locations, from open farmland and rural reservoirs to suburban and urban ponds, parks and developed areas. For this reason, geese are often found in areas heavily used by people. Geese grazing on lawns, golf courses, recreation areas and agricultural fields or leaving behind a collection of feathers or feces in unwanted areas are among the leading complaints the Department of Natural Resources’ Wildlife Resources Division (WRD) receives about geese each year. Although WRD has established a hunting season for Canada geese, these birds can sometimes continue to be a nui- sance in some areas. Despite that, it is important to re- member that Canada geese are a protected species under state and federal law. It is illegal to hunt, kill, sell, purchase or possess Canada geese except according to Georgia's mi- gratory bird regulations. The following guidelines provide legal means to help repel Canada geese. This can be a trial and error process requiring patience and persistence. The best way to prevent issues is to take early action. Suggestions and methods are detailed below. PHYSICAL BARRIERS Because geese usually walk from water to feeding areas, physical barriers are effective tools for solving many nuisance goose problems. -

Pinchin' Pennies in the Kitchen -- Tips and Recipes for Preparing Goose FN1734

NDSUNDSU EXTENSION EXTENSION SERVICE SERVICE FN1734 (Reviewed May 2019) Tips and Recipes for Preparing Goose Using game birds in your menus adds variety to your diet. Consider these tips as you expand your menu options to include game birds such as goose. Tip 1. Goose is considered a “white” meat and has Tip 5. Thaw and freeze a similar taste and texture to pheasant, duck, chicken game birds safely. or turkey, so they can be used interchangeably. • Thaw frozen meat in the Tip 2: Game meat usually has less fat, which means refrigerator in their original it tends to be dry. To compensate, use in soups and wrapping on the lowest stews, bake in oven bags, or marinate before cooking shelf. as a fillet or stir-fry. • For faster thawing, place meat in waterproof wrapping Tip 3. To keep as many juices as possible inside in cold water and change the meat, use tongs instead of a fork when cooking, the water as needed to keep and let it “rest” on a covered plate for five minutes the temperature cold. before slicing against the grain to keep meat tender. • Freeze meat in meal-size Tip 4. Handle game birds safely. pieces and packages. • Store raw wild game in the refrigerator below 40 F for Place a double layer of up to two days or freeze for longer storage. Properly freezer wrap between wrapped game birds can be stored in the freezer for individual pieces. up to six months for best quality. • Remove all air from packaging before freezing • Be sure to keep game birds outside the “danger zone” to maintain quality. -

Commitment to Product Quality and Food Safety

Commitment to Product Quality and Food Safety Schiltz Foods, Inc., and Schiltz Goose Farm, Inc., have made what we believe to be the most extensive commitment to our goose product quality and food safety in the history of goose production in the world. Our commitment starts at the farm breeding facility and continues throughout the hatchery and grow-out facility, and culminates at our processing plant, which produces quality goose products to the entire USA and other countries. Our breeding flocks are derived from a long regime of breeding work starting back in the 60’s where Schiltz Goose Farm brought in every known breed of goose in the world and created the only goose breed ever developed in the United States and has been recognized by the USDA in Beltsville, MD as being a unique breed. Our breeding flocks are kept in a clean and dry environment and have ample feed and water space in a free range environment. Each goose has 7 to 9 square feet per bird inside for inclement weather and 40 to 50 square feet per bird outside in their range pens. They are provided a clean water and feed source and all hay and bedding materials are kept under a shed to eliminate mold problems. Geese are one of the most sensitive animals to molds in the world, in the young molds can cause death and in breeding stock molds can cause sterility in the males. We adhere to strict daily water cleaning regimen which reduces the pathogen load on the breeders and the eggs in the barns. -

Raising Ducks

, . , RAISING DUCKS UNITED STATES FARMERS' PREPARED BY DEPARTMENT OF BULLETIN SCIENCE AND G AGRICULTURE NUMBER 2215 EDUCATION ADMINISTRATION CONTENTS Breeds _________ ______ _____ ____________ ______ ____ _ PAOli I ~eat b~8 ______ ___ ____ ___ _____ __ _______ __ _ _ I Egg-producingbreeds ______________________ __ __ 3 Breeding stock. ___ ____ ___ _____ _____________ ______ _ 4 Selection of breeders. _______ __________ ___ ____ _ _ 4 Breeder (acilities ___ _____ ___ ____ __ ______ __ ____ _ _ 4 EggXli~ucuon---- --- - - ---- --- -- --- --- -------- 5 HaD g eggs __ ____________________ __ ___ _____ _ 5 Incubation __ ___ __ _______ _____ ___ _______ _______ ____ 6 Artificial incuba.tion __ _____ __ . _. ___ • ______ .. __ . __ 6 Natural incubation. ____ __ • __ ____ _ . ___ ___._ . __ _ 8 Brooding and rearing __ __ ____ ______ _____ ____ __ ___ __ _ NuUition _______________ ____ _____ ____________ __ __ _ 8 10 ~arketing ____ _______________ __ ________ __ __ ______ _ II Diseases ______ ___ ______ ___ ____ ___ _____ __ __• __ ___ __ 13 lasued Mareh 1966 Slightly revi8ed AllgU/It 1969 W!l!!hington, D,C, Approved for reprinting September 1976 For ~ale by tho SU()(lrintondont of Doeumenlli, U.S, Government Printing Office Wa!hlnlton, O.C.!lru02 Stock No. 001-000-00070-6 11 RAISING DUCKS By William J. Ash, Department ot Biology, St. T..uwren(!c Uni\'crsity, Canton, N.Y. 13617' The number of ducks raised an are marketed through supply nually for meat in the United States houses and retail grocery outlets.