Vasyl´ Iermilov in the Context of Ukrainian and European Art of the First Third of the Twentieth Century Olga Lagutenko

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Anti-Trump Street Art Along the US-Mexico Border" (2019)

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Center for Advanced Research in Global CARGC Papers Communication (CARGC) 8-2019 Dreamers and Donald Trump: Anti-Trump Street Art Along the US- Mexico Border Julia Becker [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/cargc_papers Part of the Communication Commons Recommended Citation Becker, Julia, "Dreamers and Donald Trump: Anti-Trump Street Art Along the US-Mexico Border" (2019). CARGC Papers. 11. https://repository.upenn.edu/cargc_papers/11 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/cargc_papers/11 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Dreamers and Donald Trump: Anti-Trump Street Art Along the US-Mexico Border Description What tools are at hand for residents living on the US-Mexico border to respond to mainstream news and presidential-driven narratives about immigrants, immigration, and the border region? How do citizen activists living far from the border contend with President Trump’s promises to “build the wall,” enact immigration bans, and deport the millions of undocumented immigrants living in the United States? How do situated, highly localized pieces of street art engage with new media to become creative and internationally resonant sites of defiance? CARGC Paper 11, “Dreamers and Donald Trump: Anti-Trump Street Art Along the US-Mexico Border,” answers these questions through a textual analysis of street art in the border region. Drawing on her Undergraduate Honors Thesis and fieldwork she conducted at border sites in Texas, California, and Mexico in early 2018, former CARGC Undergraduate Fellow Julia Becker takes stock of the political climate in the US and Mexico, examines Donald Trump’s rhetoric about immigration, and analyzes how street art situated at the border becomes a medium of protest in response to that rhetoric. -

The Evolution of Graffiti Art

Journal of Conscious Evolution Volume 11 Article 1 Issue 11 Issue 11/ 2014 June 2018 From Primitive to Integral: The volutE ion of Graffiti Art White, Ashanti Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.ciis.edu/cejournal Part of the Clinical Psychology Commons, Cognition and Perception Commons, Cognitive Psychology Commons, Critical and Cultural Studies Commons, Family, Life Course, and Society Commons, Gender, Race, Sexuality, and Ethnicity in Communication Commons, Liberal Studies Commons, Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons, Social and Philosophical Foundations of Education Commons, Social Psychology Commons, Sociology of Culture Commons, Sociology of Religion Commons, and the Transpersonal Psychology Commons Recommended Citation White, Ashanti (2018) "From Primitive to Integral: The vE olution of Graffiti Art," Journal of Conscious Evolution: Vol. 11 : Iss. 11 , Article 1. Available at: https://digitalcommons.ciis.edu/cejournal/vol11/iss11/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals and Newsletters at Digital Commons @ CIIS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Conscious Evolution by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ CIIS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. : From Primitive to Integral: The Evolution of Graffiti Art Journal of Conscious Evolution Issue 11, 2014 From Primitive to Integral: The Evolution of Graffiti Art Ashanti White California Institute of Integral Studies ABSTRACT Art is about expression. It is neither right nor wrong. It can be beautiful or distorted. It can be influenced by pain or pleasure. It can also be motivated for selfish or selfless reasons. It is expression. Arguably, no artistic movement encompasses this more than graffiti art. -

Annual Report 1995

19 9 5 ANNUAL REPORT 1995 Annual Report Copyright © 1996, Board of Trustees, Photographic credits: Details illustrated at section openings: National Gallery of Art. All rights p. 16: photo courtesy of PaceWildenstein p. 5: Alexander Archipenko, Woman Combing Her reserved. Works of art in the National Gallery of Art's collec- Hair, 1915, Ailsa Mellon Bruce Fund, 1971.66.10 tions have been photographed by the department p. 7: Giovanni Domenico Tiepolo, Punchinello's This publication was produced by the of imaging and visual services. Other photographs Farewell to Venice, 1797/1804, Gift of Robert H. and Editors Office, National Gallery of Art, are by: Robert Shelley (pp. 12, 26, 27, 34, 37), Clarice Smith, 1979.76.4 Editor-in-chief, Frances P. Smyth Philip Charles (p. 30), Andrew Krieger (pp. 33, 59, p. 9: Jacques-Louis David, Napoleon in His Study, Editors, Tarn L. Curry, Julie Warnement 107), and William D. Wilson (p. 64). 1812, Samuel H. Kress Collection, 1961.9.15 Editorial assistance, Mariah Seagle Cover: Paul Cezanne, Boy in a Red Waistcoat (detail), p. 13: Giovanni Paolo Pannini, The Interior of the 1888-1890, Collection of Mr. and Mrs. Paul Mellon Pantheon, c. 1740, Samuel H. Kress Collection, Designed by Susan Lehmann, in Honor of the 50th Anniversary of the National 1939.1.24 Washington, DC Gallery of Art, 1995.47.5 p. 53: Jacob Jordaens, Design for a Wall Decoration (recto), 1640-1645, Ailsa Mellon Bruce Fund, Printed by Schneidereith & Sons, Title page: Jean Dubuffet, Le temps presse (Time Is 1875.13.1.a Baltimore, Maryland Running Out), 1950, The Stephen Hahn Family p. -

CUBISM and ABSTRACTION Background

015_Cubism_Abstraction.doc READINGS: CUBISM AND ABSTRACTION Background: Apollinaire, On Painting Apollinaire, Various Poems Background: Magdalena Dabrowski, "Kandinsky: Compositions" Kandinsky, Concerning the Spiritual in Art Background: Serial Music Background: Eugen Weber, CUBISM, Movements, Currents, Trends, p. 254. As part of the great campaign to break through to reality and express essentials, Paul Cezanne had developed a technique of painting in almost geometrical terms and concluded that the painter "must see in nature the cylinder, the sphere, the cone:" At the same time, the influence of African sculpture on a group of young painters and poets living in Montmartre - Picasso, Braque, Max Jacob, Apollinaire, Derain, and Andre Salmon - suggested the possibilities of simplification or schematization as a means of pointing out essential features at the expense of insignificant ones. Both Cezanne and the Africans indicated the possibility of abstracting certain qualities of the subject, using lines and planes for the purpose of emphasis. But if a subject could be analyzed into a series of significant features, it became possible (and this was the great discovery of Cubist painters) to leave the laws of perspective behind and rearrange these features in order to gain a fuller, more thorough, view of the subject. The painter could view the subject from all sides and attempt to present its various aspects all at the same time, just as they existed-simultaneously. We have here an attempt to capture yet another aspect of reality by fusing time and space in their representation as they are fused in life, but since the medium is still flat the Cubists introduced what they called a new dimension-movement. -

Defining and Understanding Street Art As It Relates to Racial Justice In

Décor-racial: Defining and Understanding Street Art as it Relates to Racial Justice in Baltimore, Maryland A thesis presented to the faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of Ohio University In partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts Meredith K. Stone August 2017 © 2017 Meredith K. Stone All Rights Reserved 2 This thesis titled Décor-racial: Defining and Understanding Street Art as it Relates to Racial Justice in Baltimore, Maryland by MEREDITH K. STONE has been approved for the Department of Geography and the College of Arts and Sciences by Geoffrey L. Buckley Professor of Geography Robert Frank Dean, College of Arts and Sciences 3 ABSTRACT STONE, MEREDITH K., M.A., August 2017, Geography Décor-racial: Defining and Understanding Street Art as it Relates to Racial Justice in Baltimore, Maryland Director of Thesis: Geoffrey L. Buckley Baltimore gained national attention in the spring of 2015 after Freddie Gray, a young black man, died while in police custody. This event sparked protests in Baltimore and other cities in the U.S. and soon became associated with the Black Lives Matter movement. One way to bring communities together, give voice to disenfranchised residents, and broadcast political and social justice messages is through street art. While it is difficult to define street art, let alone assess its impact, it is clear that many of the messages it communicates resonate with host communities. This paper investigates how street art is defined and promoted in Baltimore, how street art is used in Baltimore neighborhoods to resist oppression, and how Black Lives Matter is influencing street art in Baltimore. -

Mural Mural on the Wall: Revisiting Fair Use of Street Art

UIC REVIEW OF INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY LAW MURAL MURAL ON THE WALL: REVISITING FAIR USE OF STREET ART MADYLAN YARC ABSTRACT Mural mural on the wall, what’s the fairest use of them all? Many corporations have taken advantage of public art to promote their own brand. Corporations commission graffiti advertising campaigns because they create a spectacle that gains traction on social media. The battle rages on between the independent artists who wish to protect the exclusive rights over their art, against the corporations who argue that the public art is fair game and digital advertising is fair use of art. The Eastern Market district of Detroit is home to the Murals in the Market Festival. In January 2018, Mercedes Benz obtained a permit from the City of Detroit to photograph its G 500 SUV in specific downtown areas. On January 26, 2018, Mercedes posted six of these photographs on its Instagram account. When Defendant-artists threatened to file suit, Mercedes removed the photos from Instagram as a courtesy. In March 2019, Mercedes filed three declaratory judgment actions against the artists for non-infringement. This Comment will analyze the claims for relief put forth in Mercedes’ complaint and evaluate Defendant-artists’ arguments. Ultimately, this Comment will propose how the court should rule in the pending litigation of MBUSA LLC v. Lewis. Cite as Madylan Yarc, Mural Mural on the Wall: Revisiting Fair Use of Street Art, 19 UIC REV. INTELL. PROP. L. 267 (2020). MURAL MURAL ON THE WALL: REVISITING FAIR USE OF STREET ART MADYLAN YARC I. INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................... 267 A. -

The Writing on the Wall: Graffiti, Street Art, and a New Organic Urban Architecture Name: Isabella Siegel Faculty Adviser: Professor Laura Mcgrane

The Writing on the Wall: Graffiti, Street Art, and a New Organic Urban Architecture Name: Isabella Siegel Faculty Adviser: Professor Laura McGrane In the past half a century, graffiti and street art have grown from roots in Philadelphia to become a worldwide phenomenon. Graffiti is a method of self-expression and defiance that has mutated into new art forms that breach the status quo and gesture toward insurrection. Street art has evolved from such work, as a thriving tradition that works to articulate fears and hopes of a city’s inhabitants on the very buildings they live in. Street art, and graffiti as well, is a complex art form, especially when detangling issues of legality in the U.S. The language of “Organic Architecture” describes the way that the inhabitants of a built space work to determine what fills the empty spaces that remain. Graffiti and street art often constitute the materials with which these inhabitants build. Both genres are methods of expression of a personality, a frustration, or a window into the urban subconscious. These issues speak to Fine Arts and Art History majors, but also to those who study Political Science, History, Economics, Sociology, and Anthropology, and the Growth and Form of Cities. Art history is often used as a bridge into all of these topics, and the study of un-commissioned wall-art is no exception. The insurrectionist political nature of many pieces of street art, and much of graffiti as well, can be studied through the unique lens of someone with a background in political science. -

Frank Zappa, Captain Beefheart and the Secret History of Maximalism

Frank Zappa, Captain Beefheart and the Secret History of Maximalism Michel Delville is a writer and musician living in Liège, Belgium. He is the author of several books including J.G. Ballard and The American Prose Poem, which won the 1998 SAMLA Studies Book Award. He teaches English and American literatures, as well as comparative literatures, at the University of Liège, where he directs the Interdisciplinary Center for Applied Poetics. He has been playing and composing music since the mid-eighties. His most recently formed rock-jazz band, the Wrong Object, plays the music of Frank Zappa and a few tunes of their own (http://www.wrongobject.be.tf). Andrew Norris is a writer and musician resident in Brussels. He has worked with a number of groups as vocalist and guitarist and has a special weakness for the interface between avant garde poetry and the blues. He teaches English and translation studies in Brussels and is currently writing a book on post-epiphanic style in James Joyce. Frank Zappa, Captain Beefheart and the Secret History of Maximalism Michel Delville and Andrew Norris Cambridge published by salt publishing PO Box 937, Great Wilbraham PDO, Cambridge cb1 5jx United Kingdom All rights reserved © Michel Delville and Andrew Norris, 2005 The right of Michel Delville and Andrew Norris to be identified as the authors of this work has been asserted by them in accordance with Section 77 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. This book is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Salt Publishing. -

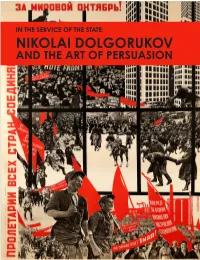

Nikolai Dolgorukov

IN THE SERVICE OF THE STATE: AGES IM CO U N R T IO E T S Y C E O L L F © T O H C E M N 2020 A E NIKOLAI DOLGORUKOV R M R R I E L L B . C AND THE ART OF PERSUASION IN THE SERVICE OF THE STATE: NIKOLAI DOLGORUKOV’ AND THE ART OF PERSUASION NIKOLAI DOLGORUKOV’ AND THE ART OF THE STATE: IN THE SERVICE © 2020 Merrill C. Berman Collection IN THE SERVICE OF THE STATE: NIKOLAI DOLGORUKOV AND THE ART OF PERSUASION 1 Published by the Merrill C. Berman Collection Series Editor, Adrian Sudhalter Concept and essay by Alla Rosenfeld, Ph.D. Content editing by Karen Kettering, Ph.D., Independent Scholar, Seattle, Washington Research assistance by Sofía Granados Dyer, graduate student, Higher School of Economics, Moscow, and Elena Emelyanova, Curator, Rare Books Department, The Russian State Library, Moscow Design, typesetting, production, and photography by Jolie Simpson Copy editing by Madeline Collins Printed and bound by www.blurb.com Plates © 2020 the Merrill C. Berman Collection Images courtesy of the Merrill C. Berman Collection unless otherwise noted © 2020 the Merrill C. Berman Collection, Rye, New York Illustrations on pages 39–41 for complete caption information. Cover: Poster: Za Mirovoi Oktiabr’! Proletarii vsekh stran soediniaites’! (Proletariat of the World, Unite Under the Banner of World October!), 1932 Lithograph 57 1/2 x 39 3/8” (146.1 x 100 cm) (p. 103) Acknowledgments We are especially grateful to Sofía Granados Dyer, graduate student at the Higher School of Economics in Moscow, for conducting research in various Russian archives as well as for assisting with the compilation of the documentary sections of this publication: Bibliography, Exhibitions, and Chronology. -

ALEXANDER ARCHIPENKO: the PARISIAN YEARS, Will Be on View at the Museum of Modern

(^<f FOR RELEASE: The Museum of Modern Art Tuesday, July 21, 1970 '1 West 53 Street, New York, N.Y. 10019 Tel. 956-6100 Cable: Modernart PRESS PREVIEW: Monday, July 20, 1970 11 a. m. - 4 p. m. ALEXANDER ARCHIPENKO: THE PARISIAN YEARS, will be on view at The Museum of Modern Art from July 21 through October 18, 1970. The exhibition, composed of 33 works, surveys the late artist's sculpture, reliefs, drawings and prints done between 1908 and 1921, the years in which he lived in Paris. William S. Lieberman, Director of the Museum's Department of Painting and Sculpture, notes, "As a sculptor, Archipenko explored spatial relationships and the movement of forms. He was also particularly interested in the uses of color in sculpture. No matter how abstract his analysis, his inspiration derived from nature. Throughout his life, he remained a solitary figure. Although an innovator, he always remained close to the Cubist tradition as it was established in France during the years of his sojourn there." In 1908, when he was 21, Archipenko left his native Russia for France, where he remained until 1921 when he moved to Berlin. Two years later he settled in the United States. He died in New York in 1964. "By 1913," comments Mr. Lieberman, "Archipenko had found the direction of his personal style, and in the same year he exhibited in the famous Armory Show in New York. The significance of his work during his heroic years in France can be clearly revealed only by comparison with the contemporaneous and Cubist sculpture of Ra3nnond Duchamp-Villon, Henri Laurens, Jacques Lipchitz, and Pablo Picasso." The illustrated checklist* that accompanies the exhibition contains an essay by the critic, Katharine Kuh, who comments that as early as 1912, Archipenko combined wood, glass, mirror, metal, canvas, and wire to manipulate light and exploit (more) *ARCHIPENK0: THE PARISIAN YEARS. -

Modern Art Collection

MODERN ART COLLECTION Alexander Archipenko Reclining 1922 Bronze 17½ × 11 × 11¼ in. (44.5 × 27.9 × 28.6 cm) Bequest of Ruth P. Phillips 2005.23.5 Widely acknowledged as the first cubist sculptor, Alexander Archipenko held a lifelong fascination with the human figure in the round. Archipenko began studies at the School of Art in Kiev in 1902 but was forced to leave in 1905 after criticizing the academicism of his instructors. He lived briefly in Moscow before settling in 1909 in Paris, where he enrolled at the École des Beaux- Arts. Yet he left after just two weeks of formal studies, believing that he could teach himself through the direct study of sculpture in the Musée du Louvre. The decade following Archipenko’s arrival in Paris proved to be his most inventive. By 1910 Archipenko began exhibiting with the cubists at the Salon des Indépendants and the Salon d’Automne, earning international renown for his nearly abstract sculptures. He was represented in many international cubist exhibitions and also exhibited in the landmark Armory Show of 1913 in New York. Following his marriage in 1921 to Angelica Schmitz, a German sculptor, Archipenko moved to Berlin, where he opened an art school. They left Berlin for New York in 1923, and Archipenko became a United States citizen in 1929. As a young artist in Paris, Archipenko began to adapt cubist techniques to sculpture. Influenced by the cubist notion of integrating the figure with surrounding space, Archipenko interchanged solids and voids so that protruding elements seemed to recede and internal features to advance. -

New Cummer Exhibit Features Work of Modern Sculptor Alexander Archipenko

New Cummer exhibit features work of modern sculptor Alexander Archipenko By Charlie Patton Sat, Jan 30, 2016 @ 10:27 am | updated Sat, Jan 30, 2016 @ 10:43 am Back Photo: 1 of 2 Though he isn’t particularly well known in the United States, where he lived the last four decades of his life, many Europeans consider Alexander Archipenko a founding father of modern sculpture. “Archipenko is of the same importance for sculpture as Picasso is for painting,” the poet Yvan Coll said in 1921. “He began to explore the interplay between interlocking voids and solids and between convex and concave surfaces, forming a sculptural equivalent to Cubist paintings’ overlapping planes and, in the process, revolutionizing modern sculpture,” reads an entry in the Encyclopedia Britannica. Now museum visitors in Jacksonville can look at Archipenko’s work at the Cummer Museum Art & Gardens, where “Archipenko: A Modern Legacy” will be on view through April 17. Archipenko was born in the Ukraine in 1887 and moved to Paris in 1908. His early work was influenced by Cubism and in 1912 he joined the Section d’Or group, which included Pablo Picasso, Marcel Duchamp and Georges Braque. In 1913, he had four sculptures and five drawings in the controversial International Exhibition of Modern Art in New York, known as the Armory Show, which was the first large exhibition of modern art in America. Viewed today as America’s introduction to the future of art, at the time the show outraged many critics, including former President Theodore Roosevelt, who declared, “That’s not art.” While in Europe, Archipenko was influenced not only of the French modernists but also of the German expressionists and the Italian futurists.