Geography of the Middle East Through the Western Lens

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mustang Daily, April 15, 1970

. '• ohlvpc Kennedy vows EOP support by FRANK ALDERETE of. the Mexican American; rTrviouHiyIKuaHAUAUi •kAutMDoui me only--- s— way— —a in 196*70 kicked te Staff Wrttar monetary and educational x person- could get himself Into a MO,000. SAC State students gave Noting that “success of the deprivations In the case of other college was to excell In athletics. $90,000 which enabled 07 more program la related to financial minorities such as Afro- "But now, Kennedy said, "we students to enroll In classes, support,Prei. Robert E. American and American Indian. can admit 2 per cent of minority Kennedy said that "he would Kennedy announced h^ ad The ability of an Individual to „ groups Into our campus. Now like to see the EOP program vocacy for the support of the rise up out of the ghetto quagmire they have a chance." expand." but that he would Economic Opportunity Program and to make himself a success is Tomorrow students will vote In rather see "a good program for a In an Interview yeeterday. a problem that has faced the a special election to determine few students than a mediocre one The problem of a lack of underprlvillged for years. whether or not ASI funds could be for a lot." motivation of an Individual Kennedy said that the "EOP used to support the EOP. Kennedy said that the program toward echolaetlc achievement la offers a minority lndivudual the Currently eight state colleges use oould and should utilise any funds ceueed by aeveral reasons— chance to make himself good and ASI funds to support their It could get. -

Under Western Stars by Howard Kazanjian and Chris Enss

Under Western Stars By Howard Kazanjian and Chris Enss King of the Cowboys Roy Rogers made his starring mo- tion picture debut in Republic Studio’s engaging western mu- sical “Under Western Stars.” Released in 1938, the charm- ing, affable Rogers portrayed the most colorful Congressman Congressional candidate Roy Rogers gets tossed into a water trough by his ever to walk up the steps of the horse to the amusement of locals gathered to hear him speak at a political rally. nation’s capital. Rogers’ character, Courtesy Library of Congress Collection. a fearless, two-gun cowboy and ranger from the western town of Sageville, is elected culties with Herbert Yates, head of Republic Studios, to office to try to win legislation favorable to dust bowl paved the way for Rogers to ride into the leading role residents. in “Under Western Stars.” Yates felt he alone was responsible for creating Autry’s success in films and Rogers represents a group of ranchers whose land wanted a portion of the revenue he made from the has dried up when a water company controlling the image he helped create. Yates demanded a percent- only dam decides to keep the coveted liquid from the age of any commercial, product endorsement, mer- hard working cattlemen. Spurred on by his secretary chandising, and personal appearance Autry made. and publicity manager, Frog Millhouse, played by Autry did not believe Yates was entitled to the money Smiley Burnette, Rogers campaigns for office. The he earned outside of the movies made for Republic portly Burnette provides much of the film’s comic re- Studios. -

International Geology Review Unroofing History of Alabama And

This article was downloaded by: [Canadian Research Knowledge Network] On: 2 March 2010 Access details: Access Details: [subscription number 918588849] Publisher Taylor & Francis Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37- 41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK International Geology Review Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.informaworld.com/smpp/title~content=t902953900 Unroofing history of Alabama and Poverty Hills basement blocks, Owens Valley, California, from apatite (U-Th)/He thermochronology Guleed A. H. Ali a; Peter W. Reiners a; Mihai N. Ducea a a Department of Geosciences, University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ, USA To cite this Article Ali, Guleed A. H., Reiners, Peter W. and Ducea, Mihai N.(2009) 'Unroofing history of Alabama and Poverty Hills basement blocks, Owens Valley, California, from apatite (U-Th)/He thermochronology', International Geology Review, 51: 9, 1034 — 1050 To link to this Article: DOI: 10.1080/00206810902965270 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00206810902965270 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Full terms and conditions of use: http://www.informaworld.com/terms-and-conditions-of-access.pdf This article may be used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contents will be complete or accurate or up to date. The accuracy of any instructions, formulae and drug doses should be independently verified with primary sources. -

Hanks, Spielberg Tops in U.S. Army Europe Hollywood Poll

Hanks, Spielberg tops in U.S. Army Europe Hollywood poll June 8, 2011 By U.S. Army Europe Public Affairs HEIDELBERG, Germany -- “Band of Brothers” narrowly edged “Saving Private Ryan” in a two-week U.S. Army Europe Web poll asking the public to select their five favorite Related Links films portraying U.S. Soldiers in Europe. Poll Results The final tally for the top spot was 128 votes to 126, revealing the powerful appeal Tom U.S. Army Europe Facebook Hanks and Steven Spielberg hold among poll participants in detailing the experiences of U.S. Army Europe Twitter WWII veterans. U.S. Army Europe YouTube The two movies were both the result of collaborations by the Hollywood A-listers. U.S. Army Europe Flickr Rounding out the top five was “The Longest Day,” a 1962 drama starring John Wayne about the events of D-Day; “Patton,” directed by Francis Ford Coppola in 1970 and starring George C. Scott as the famed American general; and “A Bridge Too Far,” a 1977 film starring Sean Connery about the failed Operation Market- Garden. The poll received a total of 814 votes and was based on the realism, entertainment value and overall quality of 20 movies featuring the U.S. Army in Europe. Some of Hollywood's biggest stars throughout history - Elvis, Clint Eastwood, Gary Cooper, Bill Murray, Gene Hackman – have all taken turns on the big screen portraying U.S. Soldiers in Europe. But to participants of the U.S. Army Europe poll, it was the lesser-known “Band of Brothers” in Easy Company who were most endearing. -

The Old Story Teller As a John the Baptist-Figure in Demille's Samson and Delilah

CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture ISSN 1481-4374 Purdue University Press ©Purdue University Volume 8 (2006) Issue 3 Article 2 The Old Story Teller as a John the Baptist-figure in DeMille's Samson and Delilah Anton Karl Kozlovic Flinders University Follow this and additional works at: https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/clcweb Part of the Comparative Literature Commons, and the Critical and Cultural Studies Commons Dedicated to the dissemination of scholarly and professional information, Purdue University Press selects, develops, and distributes quality resources in several key subject areas for which its parent university is famous, including business, technology, health, veterinary medicine, and other selected disciplines in the humanities and sciences. CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture, the peer-reviewed, full-text, and open-access learned journal in the humanities and social sciences, publishes new scholarship following tenets of the discipline of comparative literature and the field of cultural studies designated as "comparative cultural studies." Publications in the journal are indexed in the Annual Bibliography of English Language and Literature (Chadwyck-Healey), the Arts and Humanities Citation Index (Thomson Reuters ISI), the Humanities Index (Wilson), Humanities International Complete (EBSCO), the International Bibliography of the Modern Language Association of America, and Scopus (Elsevier). The journal is affiliated with the Purdue University Press monograph series of Books in Comparative Cultural Studies. Contact: <[email protected]> Recommended Citation Kozlovic, Anton Karl. "The Old Story Teller as a John the Baptist-figure in DeMille's Samson and Delilah." CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture 8.3 (2006): <https://doi.org/10.7771/1481-4374.1314> This text has been double-blind peer reviewed by 2+1 experts in the field. -

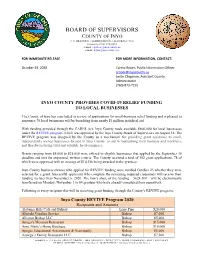

Board of Supervisors

BOARD OF SUPERVISORS COUNTY OF INYO P. O. DRAWER N INDEPENDENCE, CALIFORNIA 93526 TELEPHONE (760) 878-0373 e-mail: [email protected] e-mail: [email protected] FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE FOR MORE INFORMATION, CONTACT: October 29, 2020 Carma Roper, Public Information Officer [email protected] Leslie Chapman, Assistant County Administrator (760) 873-7191 INYO COUNTY PROVIDES COVID-19 RELIEF FUNDING TO LOCAL BUSINESSES The County of Inyo has concluded its review of applications for small-business relief funding and is pleased to announce 78 local businesses will be benefiting from nearly $1 million in federal aid. With funding provided through the CARES Act, Inyo County made available $800,000 for local businesses under the REVIVE program, which was approved by the Inyo County Board of Supervisors on August 18. The REVIVE program was designed by the County as a mechanism for providing grant assistance to small, independently owned businesses located in Inyo County, to aid in maintaining their business and workforce and thereby restoring vital and valuable local commerce. Grants ranging from $5,000 to $25,000 were offered to eligible businesses that applied by the September 18 deadline and met the expressed, written criteria. The County received a total of 102 grant applications, 78 of which were approved with an average of $10,256 being awarded to the grantees. Inyo County business owners who applied for REVIVE funding were notified October 23 whether they were selected for a grant. Successful applicants who complete the remaining required credentials will receive their funding no later than November 6, 2020. The lion’s share of the funding – $624,300 – will be electronically transferred on Monday, November 1 to 64 grantees who have already completed their paperwork. -

Ordinary Heroes: Depictions of Masculinity in World War II Film a Thesis Submitted to the Miami University Honors Program in Pa

Ordinary Heroes: Depictions of Masculinity in World War II Film A thesis submitted to the Miami University Honors Program in partial fulfillment of the requirements for University Honors with Distinction by Robert M. Dunlap May 2007 Oxford, Ohio Abstract Much work has been done investigating the historical accuracy of World War II film, but no work has been done using these films to explore social values. From a mixed film studies and historical perspective, this essay investigates movie images of American soldiers in the European Theater of Operations to analyze changing perceptions of masculinity. An examination of ten films chronologically shows a distinct change from the post-war period to the present in the depiction of American soldiers. Masculinity undergoes a marked change from the film Battleground (1949) to Band of Brothers (2001). These changes coincide with monumental shifts in American culture. Events such as the loss of the Vietnam War dramatically changed perceptions of the Second World War and the men who fought during that time period. The United States had to deal with a loss of masculinity that came with their defeat in Vietnam and that shift is reflected in these films. The soldiers depicted become more skeptical of their leadership and become more uncertain of themselves while simultaneously appearing more emotional. Over time, realistic images became acceptable and, in fact, celebrated as truthful while no less masculine. In more recent years, there is a return to the heroism of the World War II generation, with an added emotionality and dimensionality. Films reveal not only the popular opinions of the men who fought and reflect on the validity of the war, but also show contemporary views of masculinity and warfare. -

Moab Area Movie Locations Auto Tours – Discovermoab.Com - 8/21/01 Page 1

Moab Area Movie Locations Auto Tours – discovermoab.com - 8/21/01 Page 1 Moab Area Movie Locations Auto Tours Discovermoab.com Internet Brochure Series Moab Area Travel Council The Moab area has been a filming location since 1949. Enjoy this guide as a glimpse of Moab's movie past as you tour some of the most spectacular scenery in the world. All movie locations are accessible with a two-wheel drive vehicle. Locations are marked with numbered posts except for locations at Dead Horse Point State Park and Canyonlands and Arches National Parks. Movie locations on private lands are included with the landowner’s permission. Please respect the land and location sites by staying on existing roads. MOVIE LOCATIONS FEATURED IN THIS GUIDE Movie Description Map ID 1949 Wagon Master - Argosy Pictures The story of the Hole-in-the-Rock pioneers who Director: John Ford hire Johnson and Carey as wagonmasters to lead 2-F, 2-G, 2-I, Starring: Ben Johnson, Joanne Dru, Harry Carey, Jr., them to the San Juan River country 2-J, 2-K Ward Bond. 1950 Rio Grande - Republic Reunion of a family 15 years after the Civil War. Directors: John Ford & Merian C. Cooper Ridding the Fort from Indian threats involves 2-B, 2-C, 2- Starring: John Wayne, Maureen O'Hara, Ben Johnson, fighting with Indians and recovery of cavalry L Harry Carey, Jr. children from a Mexican Pueblo. 1953 Taza, Son of Cochise - Universal International 3-E Starring: Rock Hudson, Barbara Rush 1958 Warlock - 20th Century Fox The city of Warlock is terrorized by a group of Starring: Richard Widmark, Henry Fonda, Anthony cowboys. -

Movie History in Lone Pine, CA

Earl’s Diary - Saturday - February 1, 2014 Dear Loyal Readers from near and far; !Boy, was it cold last night! When I looked out the window this morning, the sun was shining and the wind still blowing. As I looked to the west, I found the reason for the cold. The wind was blowing right off the mountains covered with snow! The furnace in The Peanut felt mighty good! !Today was another sightseeing day. My travels took me to two sites in and around Lone Pine. The two sites are interconnected by subject matter. You are once again invited to join me as I travel in Lone Pine, California. !My first stop was at the Movie History Museum where I spent a couple hours enjoying the history of western movies - especially those filmed here in Lone Pine. I hurried through the place taking pictures. There were so many things to see that I went back after the photo taking to just enjoy looking and reading all the memorabilia. This was right up my alley. I spent my childhood watching cowboys and Indians, in old films showing on afternoon TV and in original TV shows from the early 50's on. My other interest is silent movies. This museum even covers that subject. ! This interesting place has an impressively large collection of movie props from all ages of film. They've got banners and posters from the 20's, sequined cowboy jumpers and instruments used by the singing cowboys of the 30's and 40's, even the guns and costumes worn by John Wayne, Clint Eastwood and several other iconic cowboy actors. -

Alabama Hills Management Plan Comments

Steve Nelson, Field Manager Sherri Lisius, Assistant Field Manager Bureau of Land Management 351 Pacu Lane, Suite 100 Bishop, CA 93514 Submitted via email: [email protected] RE: DOI-BLM-CA-C070-2020-0001-EA Bishop BLM Field Office and Alabama Hills Planning Team, Thank you for the opportunity to review and submit comments on the DOI-BLM-CA-C070-2020-0001-EA for the Alabama Hills Draft Management Plan, published July 8th 2020. Please accept these comments on behalf of Friends of the Inyo and our 1,000+ members across the state of California and country. About Friends of the Inyo & Project Background Friends of the Inyo is a conservation non-profit 501(c)(3) based in Bishop, California. We promote the conservation of public lands ranging from the eastern slopes of Yosemite to the sands of Death Valley National Park. Founded in 1986, Friends of the Inyo has over 1,000 members and executes a variety of conservation programs ranging from interpretive hikes, trail restoration, exploratory outings, and public lands policy engagement. Over our 30-year history, FOI has become an active partner with federal land management agencies in the Eastern Sierra and California Desert, including extensive work with the Bishop BLM. Friends of the Inyo was an integral partner in gaining the passage of S.47, or the John D. Dingell Jr. Conservation, Management, and Recreation Act, that designated the Alabama Hills as a National Scenic Area. Our board and staff have served this area for many years and have seen it change over time. With this designation comes the opportunity to address these changes and promote the conservation of the Alabama Hills. -

John Wayne at Fox — the Westerns

JOHN WAYNE AT FOX — THE WESTERNS ohn Wayne at Fox – not a lot of films, Bernstein’s music is as iconic and big as the federate who decides to burn his plantation but some extraordinarily entertaining Duke himself. (rather than leave it to the carpetbaggers) Jones. Interestingly, John Wayne’s first and take his people to Mexico. Wayne is a credited screen appearance, The Big Trail, A year earlier, the John Wayne Fox western Union soldier trying to sell horses – the two was for Fox. The 1930 western should have was North to Alaska, a big, sprawling comedy former enemies join up and there follows made him a star – but it didn’t. Wayne toiled western starring the Duke, Stewart Granger, much excitement, drunken brawls, a romance in all kinds of films for all kinds of studios enticing Capucine, Ernie Kovacs and teen between Wayne’s adopted Indian son and and it took John Ford and his smash hit film, heartthrob Fabian. The director was Henry Hudson’s daughter, and more excitement, all Stagecoach, to make Wayne an “overnight Hathaway, a regular at Fox, who’d helmed rousingly scored by Hugo Montenegro. sensation” and box-office star. Unlike many such classics as The House on 92nd Street, of the stars of that era, Wayne wasn’t tied to Call Northside 777, Kiss of Death, Fourteen Montenegro, born in 1925, began as an or- one studio – he bounced around from studio Hours, Niagara, Prince Valiant and many chestra leader in the mid-1950s, then going to studio, maintaining his independence. He others, as well as several films with Wayne, to Time Records, where he did several great returned to Fox in 1958 not for a western but including The Shepherd of the Hills, Legend albums in the early 1960s. -

Alabama Hills Management Plan 351 Pacu Lane, Suite 100 Bishop, CA 93514

December 23, 2019 BLM Bishop Field Office Attn: Alabama Hills Management Plan 351 Pacu Lane, Suite 100 Bishop, CA 93514 Submitted Via Email to [email protected]: RE: Access Fund Comments on Alabama Hills Management Plan Scoping Process Dear BLM Bishop Field Office Planning Staff, The Access Fund and Outdoor Alliance California (OACA) appreciate this opportunity to provide preliminary comments on the BLM’s initial scoping process for the Alabama Hills National Scenic Area (NSA) and National Recreation Area (NRA) Management Plan. The Alabama Hills provide a unique and valuable climbing and recreational experience within day trip distance of several major population centers. The distinct history, rich cultural resources, dramatic landscape, and climbing opportunities offered by the Alabama Hills have attracted increasing numbers of visitors, something which the new National Scenic Area designation1 will compound, leading to a need for proactive management strategies to mitigate growing impacts from recreation. We look forward to collaborating with the BLM on management strategies that protect both the integrity of the land and continued climbing opportunities. The Access Fund The Access Fund is a national advocacy organization whose mission keeps climbing areas open and conserves the climbing environment. A 501c(3) nonprofit and accredited land trust representing millions of climbers nationwide in all forms of climbing—rock climbing, ice climbing, mountaineering, and bouldering—the Access Fund is a US climbing advocacy organization with over 20,000 members and over 123 local affiliates. Access Fund provides climbing management expertise, stewardship, project specific funding, and educational outreach. California is one of Access Fund’s largest member states and many of our members climb regularly at the Alabama Hills.