Front & Back Matter.Pages

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

741.5 Batman..The Joker

Darwyn Cooke Timm Paul Dini OF..THE FLASH..SUPERBOY Kaley BATMAN..THE JOKER 741.5 GREEN LANTERN..AND THE JUSTICE LEAGUE OF AMERICA! MARCH 2021 - NO. 52 PLUS...KITTENPLUS...DC TV VS. ON CONAN DVD Cuoco Bruce TImm MEANWHILE Marv Wolfman Steve Englehart Marv Wolfman Englehart Wolfman Marshall Rogers. Jim Aparo Dave Cockrum Matt Wagner The Comics & Graphic Novel Bulletin of In celebration of its eighty- queror to the Justice League plus year history, DC has of Detroit to the grim’n’gritty released a slew of compila- throwdowns of the last two tions covering their iconic decades, the Justice League characters in all their mani- has been through it. So has festations. 80 Years of the the Green Lantern, whether Fastest Man Alive focuses in the guise of Alan Scott, The company’s name was Na- on the career of that Flash Hal Jordan, Guy Gardner or the futuristic Legion of Super- tional Periodical Publications, whose 1958 debut began any of the thousands of other heroes and the contemporary but the readers knew it as DC. the Silver Age of Comics. members of the Green Lan- Teen Titans. There’s not one But it also includes stories tern Corps. Space opera, badly drawn story in this Cele- Named after its breakout title featuring his Golden Age streetwise relevance, emo- Detective Comics, DC created predecessor, whose appear- tional epics—all these and bration of 75 Years. Not many the American comics industry ance in “The Flash of Two more fill the pages of 80 villains become as iconic as when it introduced Superman Worlds” (right) initiated the Years of the Emerald Knight. -

TEPOZTLAN, MEXICO – 2006 12Th International Symposium on Vulcanospeleology Greg Middleton

TEPOZTLAN, MEXICO – 2006 12th International Symposium on Vulcanospeleology Greg Middleton ABSTRACT The 12th International Symposium on Vulcanospeleology was held at Tepoztlán, Mexico in July 2006. Field trips included visits to the spatter cones and vents of Los Cuescomates, Cueva del Diablo, Chimalacatepec, Iglesia Cave, Cueva del Ferrocarril, Cantona archaeological site, Alchichica Maar, El Volcancillo crater and tubes, Rio Actopan (river rafting). The author later visited some unusual volcanic caves near Colonia Moderna, northwest of Guadalajara. WELCOME TO MEXICO small band of helpers. Attendees included Arriving at Mexico City airport just before IUS Volcanic Caves Commission Chair Jan midnight on 1 July, after flying from Sydney Paul Van Der Pas (and Bep) (Netherlands), a for 25 hours (with a 3 hour stop-over in contingent from South Korea (Kyung Sik Santiago de Chile), can be slightly Woo, Kwang Choon Lee, In-Seok Son and harrowing. Then to find the last bus to others), a contingent from the Azores Cuernavaca (fare 1,100 Peso or US$10) (Paulino Costa, João C. Nunes, Paulo departed at 11:30 pm and be confronted by a Barcelos, João P. Constância and others), rather dubious-looking character offering a Marcus & Robin Gary, Diana Northup, Ken ‘taxi’ to take you there for US$160, can be Ingham and Peter Ruplinger from the USA, positively unnerving. Fortunately, with only Stephan Kempe and Horst-Volker Henschel my wallet considerably lighter, I made it to from Germany, Ed Waters and (of course) the small village of Tepoztlán, arriving at the Chris Wood from the UK, together with a Hospedaje Los Reyes at 1:45 am. -

Batman: Year One by Frank Miller and David Mazzucchelli Study Guide By

Graphic Novel Study Group Study Guides Batman: Year One By Frank Miller and David Mazzucchelli Study guide by 1. In 1986, Miller and Mazzucchelli were charged with updating the classic character of Batman. DC Comics wanted to give the origin story “depth, complexity, a wider context.” Did Miller and Mazzucchelli succeed? 2. Why or why not? Give specific examples. 3. We meet Jimmy Gordon and Bruce Wayne at roughly the same moment in the novel. How are they portrayed differently, right from the beginning? Are these initial impressions in line with what we come to know about both characters later? 4. In both Jimmy and Bruce’s initial scenes, how are color and drawing style used to create an atmosphere, or to set them apart – their characters and their surroundings? Give a specific example for each. 5. Batman’s origin story is a familiar one to most readers. How do Miller and Mazzucchelli embroider the basic story? 6. What effect do their additions or subtractions have on your understanding of Bruce Wayne? 7. What are the major plots and subplots contained in the novel? 8. Where are the moments of high tension in the novel? 9. What happens directly before and after each one? How does the juxtaposition of low-tension and high-tension scenes or the repetition of high-tension scenes affect the pacing of the novel? 10. How have Jimmy Gordon and Bruce Wayne/Batman evolved over the course of the novel? How do we as readers understand this? Give specific examples. . -

Crossmedia Adaptation and the Development of Continuity in the Dc Animated Universe

“INFINITE EARTHS”: CROSSMEDIA ADAPTATION AND THE DEVELOPMENT OF CONTINUITY IN THE DC ANIMATED UNIVERSE Alex Nader A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS May 2015 Committee: Jeff Brown, Advisor Becca Cragin © 2015 Alexander Nader All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Jeff Brown, Advisor This thesis examines the process of adapting comic book properties into other visual media. I focus on the DC Animated Universe, the popular adaptation of DC Comics characters and concepts into all-ages programming. This adapted universe started with Batman: The Animated Series and comprised several shows on multiple networks, all of which fit into a shared universe based on their comic book counterparts. The adaptation of these properties is heavily reliant to intertextuality across DC Comics media. The shared universe developed within the television medium acted as an early example of comic book media adapting the idea of shared universes, a process that has been replicated with extreme financial success by DC and Marvel (in various stages of fruition). I address the process of adapting DC Comics properties in television, dividing it into “strict” or “loose” adaptations, as well as derivative adaptations that add new material to the comic book canon. This process was initially slow, exploding after the first series (Batman: The Animated Series) changed networks and Saturday morning cartoons flourished, allowing for more opportunities for producers to create content. References, crossover episodes, and the later series Justice League Unlimited allowed producers to utilize this shared universe to develop otherwise impossible adaptations that often became lasting additions to DC Comics publishing. -

Threat, Authoritarianism, and Depictions of Crime, Law, and Order in Batman Films Brandon Bosch University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected]

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Sociology Department, Faculty Publications Sociology, Department of 4-2-2016 “Why So Serious?” Threat, Authoritarianism, and Depictions of Crime, Law, and Order in Batman Films Brandon Bosch University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/sociologyfacpub Part of the Criminal Law Commons, Criminology Commons, Family, Life Course, and Society Commons, Public Affairs, Public Policy and Public Administration Commons, and the Social Control, Law, Crime, and Deviance Commons Bosch, Brandon, "“Why So Serious?” Threat, Authoritarianism, and Depictions of Crime, Law, and Order in Batman Films" (2016). Sociology Department, Faculty Publications. 287. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/sociologyfacpub/287 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Sociology, Department of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Sociology Department, Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. VOLUME 17, ISSUE 1, PAGES 37–54 (2016) Criminology, Criminal Justice Law, & Society E-ISSN 2332-886X Available online at https://scholasticahq.com/criminology-criminal-justice-law-society/ “Why So Serious?” Threat, Authoritarianism, and Depictions of Crime, Law, and Order in Batman Films Brandon Bosch University of Nebraska-Lincoln A B S T R A C T A N D A R T I C L E I N F O R M A T I O N Drawing on research on authoritarianism, this study analyzes the relationship between levels of threat in society and representations of crime, law, and order in mass media, with a particular emphasis on the superhero genre. -

Monday Evening Television

DIARIES AJAMA P THE ERNEST & FRANK WORTH Y MAR FRIENDS BETWEEN BIZARRO OOP ALLEY LEE EDISON OF MIND BRILLIANT Monday Evening Television 6:00 6:30 7:00 7:30 8:00 8:30 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 11:30 12:00 2 News at 6:00pm Entertainment To- Kevin Can Wait: Man With a 2 Broke Girls (N) The Odd Couple: I Scorpion: Bat Poop Crazy. The team 2 News at (10:37) The Late Show With Stephen (11:39) The Late Late Show With KUTV (N) (CC) night (N) (s) (CC) Hallow-We-Ain’t- Plan (N) (s) (CC) (s) (CC) (TV14) Kid, You Not. (N) investigates a bat population. (N) (s) 10:00pm (N) (CC) Colbert: Ruth Wilson; J.B. Smoove. James Corden: Harry Connick Jr.; Home. (N) (TVPG) (TVPG) (TVPG) (CC) (TV14) (N) (s) (TVPG) Alice Eve. (N) (s) (CC) (TV14) ABC 4 Utah News Inside Edition (N) Dancing With the Stars: Halloween-themed routines. (N Same-day Tape) (s) (9:01) All Access Nashville: Celebrat- ABC 4 Utah News (10:35) Jimmy Kimmel Live (N) (s) (11:37) Nightline (12:07) Access KTVX at 6pm (N) (s) (CC) (TVPG) (CC) (TVPG) ing the CMA Awards With Robin at 10pm (N) (CC) (TV14) (N) (CC) (TVG) Hollywood (N) (s) Roberts (N) (s) (CC) (CC) (TVPG) KSL 5 News at 6p KSL 5 News at The Voice: The Knockouts, Part 3. Artists perform for the coaches. (N) (s) (9:01) Timeless: The Alamo. The KSL 5 News at 10 (10:34) The Tonight Show Starring (11:37) Late Night With Seth Meyers: KSL (N) (CC) 6:30p (CC) (CC) (TVPG) team is stranded inside the Alamo. -

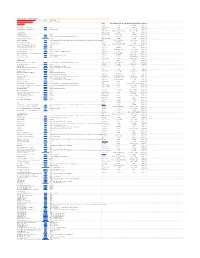

THANKSGIVING and BLACK FRIDAY STORE HOURS --->> ---> ---> Always Do a Price Comparison on Amazon Here Store Price Notes

THANKSGIVING AND BLACK FRIDAY STORE HOURS --->> ---> ---> Always do a price comparison on Amazon Here Store Price Notes KOHL's Coupon Codes: $15SAVEBIG15 Kohl's Cash 15% for everyoff through $50 spent 11/24 through 11/25 Electronics Store Thanksgiving Day Store HoursBlack Friday Store Hours Confirmed DVD PLAYERS AAFES Closed 4:00 AM Projected RCA 10" Dual Screen Portable DVD Player Walmart $59.00 Ace Hardware Open Open Confirmed Sylvania 7" Dual-Screen Portable DVD Player Shopko $49.99 Doorbuster Apple Closed 8 am to 10 pm Projected Babies"R"Us 5 pm to 11 pm on Friday Closes at 11 pm Projected BLU-RAY PLAYERS Barnes & Noble Closed Open Confirmed LG 4K Blu-Ray Disc Player Walmart $99.00 Bass Pro Shops 8 am to 6 pm 5:00 AM Confirmed LG 4K Ultra HD 3D Blu-Ray Player Best Buy $99.99 Deals online 11/24 at 12:01am, Doors open at 5pm; Only at Best Buy Bealls 6 pm to 11 pm 6 am to 10 pm Confirmed LG 4K Ultra-HD Blu-Ray Player - Model UP870 Dell Home & Home Office$109.99 Bed Bath & Beyond Closed 6:00 AM Confirmed Samsung 4K Blu-Ray Player Kohl's $129.99 Shop Doorbusters online at 12:01 a.m. (CT) Thursday 11/23, and in store Thursday at 5 p.m.* + Get $15 in Kohl's Cash for every $50 SpentBelk 4 pm to 1 am Friday 6 am to 10 pm Confirmed Samsung 4K Ultra Blu-Ray Player Shopko $169.99 Doorbuster Best Buy 5:00 PM 8:00 AM Confirmed Samsung Blu-Ray Player with Built-In WiFi BJ's $44.99 Save 11/17-11/27 Big Lots 7 am to 12 am (midnight) 6:00 AM Confirmed Samsung Streaming 3K Ultra HD Wired Blu-Ray Player Best Buy $127.99 BJ's Wholesale Club Closed 7 am -

Relationality and Masculinity in Superhero Narratives Kevin Lee Chiat Bachelor of Arts (Communication Studies) with Second Class Honours

i Being a Superhero is Amazing, Everyone Should Try It: Relationality and Masculinity in Superhero Narratives Kevin Lee Chiat Bachelor of Arts (Communication Studies) with Second Class Honours This thesis is presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of The University of Western Australia School of Humanities 2021 ii THESIS DECLARATION I, Kevin Chiat, certify that: This thesis has been substantially accomplished during enrolment in this degree. This thesis does not contain material which has been submitted for the award of any other degree or diploma in my name, in any university or other tertiary institution. In the future, no part of this thesis will be used in a submission in my name, for any other degree or diploma in any university or other tertiary institution without the prior approval of The University of Western Australia and where applicable, any partner institution responsible for the joint-award of this degree. This thesis does not contain any material previously published or written by another person, except where due reference has been made in the text. This thesis does not violate or infringe any copyright, trademark, patent, or other rights whatsoever of any person. This thesis does not contain work that I have published, nor work under review for publication. Signature Date: 17/12/2020 ii iii ABSTRACT Since the development of the superhero genre in the late 1930s it has been a contentious area of cultural discourse, particularly concerning its depictions of gender politics. A major critique of the genre is that it simply represents an adolescent male power fantasy; and presents a world view that valorises masculinist individualism. -

Activity Kit Proudly Presented By

ACTIVITY KIT PROUDLY PRESENTED BY: #BatmanDay dccomics.com/batmanday #Batman80 Entertainment Inc. (s19) Inc. Entertainment WB SHIELD: TM & © Warner Bros. Bros. Warner © & TM SHIELD: WB and elements © & TM DC Comics. DC TM & © elements and WWW.INSIGHTEDITIONS.COM BATMAN and all related characters characters related all and BATMAN Copyright © 2019 DC Comics Comics DC 2019 © Copyright ANSWERS 1. ALFRED PENNYWORTH 2. JAMES GORDON 3. HARVEY DENT 4. BARBARA GORDON 5. KILLER CROC 5. LRELKI CRCO LRELKI 5. 4. ARARBAB DRONGO ARARBAB 4. 3. VHYRAE TEND VHYRAE 3. 2. SEAJM GODORN SEAJM 2. 1. DELFRA ROTPYHNWNE DELFRA 1. WORD SCRAMBLE WORD BATMAN TRIVIA 1. WHO IS BEHIND THE MASK OF THE DARK KNIGHT? 2. WHICH CITY DOES BATMAN PROTECT? 3. WHO IS BATMAN'S SIDEKICK? 4. HARLEEN QUINZEL IS THE REAL NAME OF WHICH VILLAIN? 5. WHAT IS THE NAME OF BATMAN'S FAMOUS, MULTI-PURPOSE VEHICLE? 6. WHAT IS CATWOMAN'S REAL NAME? 7. WHEN JIM GORDON NEEDS TO GET IN TOUCH WITH BATMAN, WHAT DOES HE LIGHT? 9. MR. FREEZE MR. 9. 8. THOMAS AND MARTHA WAYNE MARTHA AND THOMAS 8. 8. WHAT ARE THE NAMES OF BATMAN'S PARENTS? BAT-SIGNAL THE 7. 6. SELINA KYLE SELINA 6. 5. BATMOBILE 5. 4. HARLEY QUINN HARLEY 4. 3. ROBIN 3. 9. WHICH BATMAN VILLAIN USES ICE TO FREEZE HIS ENEMIES? CITY GOTHAM 2. 1. BRUCE WAYNE BRUCE 1. ANSWERS Copyright © 2019 DC Comics WWW.INSIGHTEDITIONS.COM BATMAN and all related characters and elements © & TM DC Comics. WB SHIELD: TM & © Warner Bros. Entertainment Inc. (s19) WORD SEARCH ALFRED BANE BATMOBILE JOKER ROBIN ARKHAM BATMAN CATWOMAN RIDDLER SCARECROW I B W F P -

The Evolution of Batman and His Audiences

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University English Theses Department of English 12-2009 Static, Yet Fluctuating: The Evolution of Batman and His Audiences Perry Dupre Dantzler Georgia State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/english_theses Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Dantzler, Perry Dupre, "Static, Yet Fluctuating: The Evolution of Batman and His Audiences." Thesis, Georgia State University, 2009. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/english_theses/73 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of English at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in English Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STATIC, YET FLUCTUATING: THE EVOLUTION OF BATMAN AND HIS AUDIENCES by PERRY DUPRE DANTZLER Under the Direction of H. Calvin Thomas ABSTRACT The Batman media franchise (comics, movies, novels, television, and cartoons) is unique because no other form of written or visual texts has as many artists, audiences, and forms of expression. Understanding the various artists and audiences and what Batman means to them is to understand changing trends and thinking in American culture. The character of Batman has developed into a symbol with relevant characteristics that develop and evolve with each new story and new author. The Batman canon has become so large and contains so many different audiences that it has become a franchise that can morph to fit any group of viewers/readers. Our understanding of Batman and the many readings of him gives us insight into ourselves as a culture in our particular place in history. -

Extending and Visualizing Authorship in Comics Studies

AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS OF Nicholas A. Brown for the degree of Master of Arts in English presented on April 30, 2015 Title: Extending and Visualizing Authorship in Comics Studies. Abstract approved: ________________________________________________________________________ Tim T. Jensen Ehren H. Pflugfelder This thesis complicates the traditional associations between authorship and alphabetic composition within the comics medium and examines how the contributions of line artists and writers differ and may alter an audience's perceptions of the medium. As a fundamentally multimodal and collaborative work, the popular superhero comic muddies authorial claims and requires further investigations should we desire to describe authorship more accurately and equitably. How might our recognition of the visual author alter our understandings of the author construct within, and beyond, comics? In this pursuit, I argue that the terminology available to us determines how deeply we may understand a topic and examine instances in which scholars have attempted to develop on a discipline's body of terminology by borrowing from another. Although helpful at first, these efforts produce limited success, and discipline-specific terms become more necessary. To this end, I present the visual/alphabetic author distinction to recognize the possibility of authorial intent through the visual mode. This split explicitly recognizes the possibility of multimodal and collaborative authorships and forces us to re-examine our beliefs about authorship more generally. Examining the editors' note, an instance of visual plagiarism, and the MLA citation for graphic narratives, I argue for recognition of alternative authorships in comics and forecast how our understandings may change based on the visual/alphabetic split. -

47-Blueprints.Pdf

CAT-TALES BBLUEPRINTS CAT-TALES BBLUEPRINTS By Chris Dee Edited by David L. COPYRIGHT © 2006 BY CHRIS DEE ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. BATMAN, CATWOMAN, GOTHAM CITY, ET AL CREATED BY BOB KANE, PROPERTY OF DC ENTERTAINMENT, USED WITHOUT PERMISSION BLUEPRINTS Many Gothamites didn’t even know they existed, these rarified pockets of the world where the subtle and unconscious application of wealth and influence had fended off the ravages of time and change. One of these pockets was right in their midst, only a few minutes from the heart of the city: the Gotham suburb of Bristol. The ancient sycamores that once shaded Iroquois hunters tracking deer and pheasant had never been pulled down to build tract houses on quarter-acre plots. The roads were paved, but they didn’t lead to stripmalls or “superstores.” They led, under a canopy of those same leafy sycamores, to quaint, family-owned businesses like Perdita’s Florals and Harriman’s Gourmet Pantry. Mr. Harriman still wore a clean white apron, kept the customer accounts in a handwritten ledger, and tallied them himself at the end of each month. He didn’t bother sending the bill to Wayne Manor. He merely folded it in a brown envelope, wrote WAYNE on the flap, and handed it to Alfred Pennyworth when he came in the next Monday or Thursday to do his twice-weekly shopping. Alfred slipped the envelope into his pocket, for he would never insult Mr. Harriman by checking it in front of him. He would open it tonight while having his nightcap with Miss Selina’s little friend Nutmeg, and reconcile it with the records kept on his laptop.