The Year in Revie Review the Year in Review

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Capturing the Starlight

Capturing the starlight Welcome Celestial sights for 2016 Welcome to the 2nd edition of the IFAS calendar, highlighting many items of interest during 2016 for the keen sky watcher. Eclipses Occultations Our first calendar was a great success and let IFAS buy and A total solar eclipse on March 9th tracks across Sumatra, A daylight occultation of Venus occurs on April 6th, while the distribute 1,500 eclipse shades free in time for the March 20th Borneo, Sulawesi, and a narrow span of the Pacific Ocean. East planet Jupiter lies a scant 4° from the Sun when occulted on solar eclipse. Due to various issues we have been unable to Asia, Australia, and Pacific regions, see a partial eclipse. September 30th. This is a very risky event to observe due to print up the calendar in time for distribution before the start of Jupiter’s nearness to the Sun. Neptune is occulted 3 times in The penumbral lunar eclipse on March 23rd is visible from 2016. As a result we have made the calendar freely available 2016 from the UK/Ireland — compute local circumstances via the Americas, Asia, and Australia. This eclipse has a maximum for people to download. Until the 2017 calendar, we wish you eco.mtk.nao.ac.jp/cgi-bin/koyomi/occulx_p_en.cgi the astronomer’s adieu; Clear skies! magnitude of 77%. Nothing will be seen of the penumbral lunar eclipse of August 18th as the Moon's disk barely brushes the Asteroid occultations are only given for stars brighter than Contact us, link up with the Irish astronomy community, or outer edge of the northern part of the Earth's penumbral shadow. -

Determination of the Spectroscopic Stellar Parameters for 257 Field Giant

Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 000, 1–18 (2015) Printed 10 May 2018 (MN LATEX style file v2.2) Determination of the spectroscopic stellar parameters for 257 field giant stars⋆⋆ S. Alves1,2†, L. Benamati3,4,5, N. C. Santos3,4,5, V. Zh. Adibekyan3,4, S. G. Sousa3,4,5, G. Israelian6,7, J. R. De Medeiros8, C. Lovis9, S. Udry9 1 Instituto de Astrof´ısica, Pontificia Universidad Cat´olica de Chile, Av. Vicu˜na Mackenna 4860, 782-0436, Macul, Santiago, Chile 2 CAPES Foundation, Ministry of Education of Brazil, Bras´ılia / DF, Brazil 3 Centro de Astrof´ısica da Universidade do Porto, Rua das Estrelas, 4150-762 Porto, Portugal 4 Instituto de Astrof´ısica e Ciˆencias do Espa¸co, Universidade do Porto, Rua das Estrelas, PT4150-762 Porto, Portugal 5 Departamento de F´ısica e Astronomia, Faculdade de Ciˆencias da Universidade do Porto, Portugal 6 Instituto de Astrof´ısica de Canarias, 38200 La Laguna, Tenerife, Spain 7 Departamento de Astrof´ısica, Universidad de La Laguna, 38206 La Laguna, Tenerife, Spain 8 Departamento de F´ısica Te´orica e Experimental, Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Norte, Campus Universit´ario Lagoa Nova, 59072-970 Natal, RN, Brasil 9 Observatoire de Gen`eve, Universit´ede Gen`eve, 51 ch. des Maillettes, 1290, Sauverny, Switzerland Accepted 2015 January 26. Received 2015 January 20; in original form 2014 November 26 ABSTRACT The study of stellar parameters of planet-hosting stars, such as metallicity and chemical abun- dances, help us to understand the theory of planet formation and stellar evolution. Here, we present a catalogue of accurate stellar atmospheric parameters and iron abundances for a sam- ple of 257 K and G field evolved stars that are being surveyed for planets using precise radial– velocity measurements as part of the CORALIE programme to search for planets around giants. -

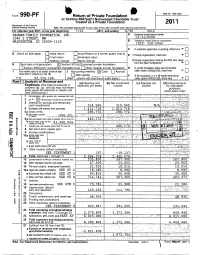

0 Return of Private Foundation

16 0 OMB No 1545.0052 Form 990 -PF Return of Private Foundation or Section 4947(aXl) Nonexempt Charitable Trust Treated as a Private Foundation 2011 Department of the Treasury Internal Revenue Service Note . The foundation may be able to use a copy of this return to satisfy state reporting requi For calendar year 2011 , or tax year beginning 7/01 , 2011, and ending 6/30 , 2012 BAUMAN FAMILY FOUNDATION, INC. A Employer identification number 2040 S STREET, NW 13-3119290 WASHINGTON, DC 20009-1110 B Telephone number (see the instructions) (202) 328-2040 C If exemntlon aonllcatlon Is oendlna. check here n G Check all that apply Initial return Initial Return of a former public charity D 1 Foreign organizations, check here Final return Amended return Address change Name change 2 Foreign organizations meeting the 85% test, check q here and attach computation H Check type of organization X Section 501 (c)(3) exempt private foundation Section 4947(a)(1 ) nonexem pt charitable trust Other taxable p rivate foundation E If private foundation status was terminated q Fair market value of all assets at end of year J Accounting method: X Cash Accrual under section 507(b)(1)(A), check here (from Part ll, column (c), line 16) [] Other (specify) F If the foundation is in a 60-month termination $ 93, 310, 166. I (Part 1, column (d) must be on cash basis under section 507(b)(1)(B'. check here ;Part:I T Analysis of Revenue and (a) Revenue and (b) Net investment (c) Adjusted net (d) Disbursements Expenses (The total of amounts in expenses per books income income for charitable columns (b), (c), and (d) may not neces- purposes sarily equal the amounts in column (a) (cash basis only) (see instructions) ) 1 Contributions, gifts, grants, etc, received (att sch) 2 Ck rf the toundn is not req to att Sch B = = ? .= -_ - - 3 Interest on savings and temporary '-_ ' - - cash investments 314 545. -

Redox DAS Artist List for Period: 01.08.2018

Page: 1 Redox D.A.S. Artist List for period: 01.08.2018 - 31.08.2018 Date time: Number: Title: Artist: Publisher Lang: 01.08.2018 00:00:21 HD 15025 KRI BOHEM SLO 01.08.2018 00:04:28 HD 62653 LAST SUMMER SONG THE STRANGE ANG 01.08.2018 00:08:36 HD 62142 KO CVETIJO CESNJE DUCO SLO 01.08.2018 00:12:07 HD 17160 BABY SMILE THE KELLY FAMILY ANG 01.08.2018 00:15:37 HD 13144 DRUGACNO NEBO AVTOMOBILI SLO 01.08.2018 00:19:16 HD 58199 SAILOR JARDIER ANG 01.08.2018 00:23:15 HD 43493 ANGELS THE BASEBALLS ANG 01.08.2018 00:26:30 HD 46352 NE BOM POZABIL NA STARE CASE ALENKA GODEC SLO 01.08.2018 00:29:53 HD 40133 BE THE ONE THE TING TINGS ANG 01.08.2018 00:32:45 HD 05300 I'LL REMEMBER MADONNA ANG 01.08.2018 00:37:01 HD 61402 REVENGE (FEAT. EMINEM) PINK ANG 01.08.2018 00:40:44 HD 61537 NI PREDAJE, NI UMIKA BQL IN NIKA ZORJAN SLO 01.08.2018 00:43:42 HD 05176 MY DESTINY LIONEL RICHIE ANG 01.08.2018 00:48:29 HD 60173 AVENIR LOUANE FRA 01.08.2018 00:51:32 HD 03848 CLOSE ENCOUNTERS CLOUSEAU ANG 01.08.2018 00:55:12 HD 61938 PLEASE SAMANTHA HARVEY ANG 01.08.2018 00:58:05 HD 61551 LEPA SI NINA PUSLAR SLO 01.08.2018 01:01:46 HD 29595 HEY JOE (LIVE) WILLY DEVILLE ANG 01.08.2018 01:06:40 HD 01539 TO PRI NAS MOZNO VLADO KRESLIN SLO 01.08.2018 01:11:06 HD 61855 ALFIE'S SONG (NOT SO TYPICAL LOVEBLEACHERS SONG) ANG 01.08.2018 01:14:04 HD 29265 WISH YOU WERE HERE WYCLEF JEAN ANG 01.08.2018 01:18:01 HD 28058 CRTA DANILO KOCJANCIC SLO 01.08.2018 01:21:29 HD 36930 THE RISING BRUCE SPRINGSTEEN ANG 01.08.2018 01:26:08 HD 60103 A MATTER OF TRUST BILLY JOEL ANG 01.08.2018 01:30:10 -

7-9 Booklist by Title - Full

7-9 Booklist by Title - Full When using this booklist, please be aware of the need for guidance to ensure students select texts considered appropriate for their age, interest and maturity levels. This title also appears on the 5-6 booklist. This title is usually read by students in years 9, 10 and above. PRC Title/Author Publisher Year ISBN Annotations 825 10 little insects Wilkins Farago Pty 2012 9780987109910 10 intelligent insects, each with something to hide, are invited to a Cali, Davide & Pianina, V (ill) Ltd secluded island for the weekend. One by one, unusual things start to happen and they begin tracking a murderer. 5891 100 things to know about science Usborne Publishing 2015 9781409582182 Find out about familiar and less familiar topics, from the Earth's Frith, Alex & Lacey, Minna & Martin, Jerome Ltd magnetic poles to spider venom and black holes. Lots of facts and & Melmoth, Jonathan colourful infographics cover one hundred science topics. 87206 101 ways to save the earth Frances Lincoln 2008 9781845079246 This book deals with the fragility of our planet's ecosystem. Topics Bellamy, David & Dann, Penny (ill) include household recycling, earth-friendly shopping tips, biodegradable products and links for further information. 4983 1836 Do you dare: Fighting bones Penguin Books 2014 9780143307556 In 1836, Irish brothers, Danny and Declan Sheehan, are inmates at Laguna, Sofie Australia Tasmania's Point Puer prison for convict boys. When tragedy strikes and the prison bully is on the rampage, escape is the brothers only chance to survive. 7080 1854 Do you dare: Eureka boys Puffin Australia 2015 9780143308454 Henry lives with his father and sister on the Victorian goldfields. -

STATE CHAMPS Magicvalley.Com M ORE THAN a DROP Dept

Business, Idaho jobless rate drops for first time in four years on Religion 3 SATURDAY May 21, 2011 TIMES-NEWS 75 CENTS Jerome girls take 4A track title, Sports 1 STATE CHAMPS Magicvalley.com M ORE THAN A DROP Dept. of IN THE BUCKET Xavier Correction likely to run own to close T.F. finances work center Charter management company Paragon to Cut could save $900K a year, close shop in Idaho stave off employee furloughs By Amy Huddleston By Nick Coltrain Times-News writer Times-News writer After a tumultuous relation- ship over the last three months, The Idaho Department of Correction will Xavier Charter School and pri- close its Twin Falls Work Center Aug. 1 — ship- vate school management compa- ping its 78 prisoners to other facilities in the ny Paragon Schools are not only state, offering new positions to its 13 employees ending their relationship, but and hopefully saving more than $900,000 in Paragon is also shutting down the process,officials said. shop in Idaho. IDOC Director Brent Reinke said his depart- Paragon CEO Brandon Fair- ment hopes to turn those savings into fewer banks said Friday his company has furloughs for his employees. They won’t know taken steps to wrap up its agree- until the fall how much money is saved by clos- ments in Idaho in preparation to ing the center, he said, or what that extra cash leave the state, mostly due to its means for furloughs. The Twin Falls Work Cen- involvement with Xavier. ter has been in operation since July 1992. -

The British Astronomical Association Handbook 2016

THE HANDBOOK OF THE BRITISH ASTRONOMICAL ASSOCIATION 2016 2015 October ISSN 0068–130–X CONTENTS CALENDAR 2016 . 2 PREFACE . 3 HIGHLIGHTS FOR 2016 . 4 SKY DIARY . .. 5 VISIBILITY OF PLANETS . 6 RISING AND SETTING OF THE PLANETS IN LATITUDES 52°N AND 35°S . 7-8 ECLIPSES . 9-15 TIME . 16-17 EARTH . 18 SUN . 19-21 LUNAR LIBRATION . 22 MOON . 23 MOONRISE AND MOONSET . 24-27 SUN’S SELENOGRAPHIC COLONGITUDE . 28 LUNAR OCCULTATIONS . 29-35 GRAZING LUNAR OCCULTATIONS . 36-37 APPEARANCE OF PLANETS . 38 MERCURY . 39-40 VENUS . 41 MARS . 42-43 ASTEROIDS . 44-49 ASTEROID OCCULTATIONS .. 50-53 ASTEROIDS: FAVOURABLE OBSERVING OPPORTUNITIES . 54-56 NEO CLOSE APPROACHES TO EARTH . 57 JUPITER . .. 58-62 SATELLITES OF JUPITER . 62-66 JUPITER ECLIPSES, OCCULTATIONS AND TRANSITS . 67-76 SATURN . 77-80 SATELLITES OF SATURN . 81-84 URANUS . 85 NEPTUNE . 86 TRANS–NEPTUNIAN & SCATTERED DISK OBJECTS . 87 DWARF PLANETS . 88-91 COMETS . 92-96 METEOR DIARY . 97-99 VARIABLE STARS (RZ Cassiopeiae; Algol; λ Tauri) . 100-101 MIRA STARS . 102 VARIABLE STAR OF THE YEAR (Z Andromedæ) . .. 103-105 EPHEMERIDES OF VISUAL BINARY STARS . 106-107 BRIGHT STARS . 108 ACTIVE GALAXIES . 109 PLANETS – EXPLANATION OF TABLES . 110 ELEMENTS OF PLANETARY ORBITS . 111 ASTRONOMICAL AND PHYSICAL CONSTANTS . 112-113 INTERNET RESOURCES . 114-115 GREEK ALPHABET . 115 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS / ERRATA . 116 Front Cover: The previous Transit of Mercury - as taken through a Hydrogen Alpha telescope on 08 November 2006 at 08:19-22UT (D.C.Parker) British Astronomical Association HANDBOOK FOR 2016 NINETY–FIFTH -

December 2019

Page: 1 Redox D.A.S. Artist List for period: 01.12.2019 - 31.12.2019 Date time: Number: Title: Artist: Publisher Lang: 01.12.2019 00:03:06 HD 10072 I MASCHI GIANNA NANNINI ITA 01.12.2019 00:07:20 HD 14286 YOU ALL DAT BAHA MEN ANG 01.12.2019 00:10:40 HD 62332 NO TEARS LEFT TO CRY ARIANA GRANDE ANG 01.12.2019 00:14:08 HD 05349 EMOTIONS MARIAH CAREY ANG 01.12.2019 00:18:14 HD 21034 NA PRIMORSKO REQUIEM SLO 01.12.2019 00:23:18 HD 13520 SHE'S SO HIGH KURT NILSEN ANG 01.12.2019 00:27:20 HD 33297 ABRACADABRA STEVE MILLER ANG 01.12.2019 00:30:59 HD 60614 ATTENTION CHARLIE PUTH ANG 01.12.2019 00:34:25 HD 45281 CAKAL SN TE KO KRETEN MI2 SLO 01.12.2019 00:38:42 HD 06037 MERCY MERCY ME ROBERT PALMER ANG 01.12.2019 00:44:28 HD 56521 HEROES MANS ZELMERLOW ANG 01.12.2019 00:47:40 HD 03278 KOKOMO BEACH BOYS ANG 01.12.2019 00:51:07 HD 50270 VEC OD LAJFA ZLATKO SLO 01.12.2019 00:55:07 HD 61566 LEAVE A LIGHT ON TOM WALKER ANG 01.12.2019 00:58:10 HD 63959 CRAZY TO LOVE YOU DECCO, ALEX CLARE ANG 01.12.2019 01:00:58 HD 06769 UN-BREAK MY HEART TONI BRAXTON ANG 01.12.2019 01:05:16 HD 13010 NOCOJ LJUBILA BI SE S TEBOJ C'EST LA VIE SLO 01.12.2019 01:10:00 HD 40201 REHAB RIHANNA ANG 01.12.2019 01:13:56 HD 35226 HAPPY HOUR AGAIN THE HOUSEMARTINS ANG 01.12.2019 01:16:17 HD 63697 I DON'T CARE ED SHEERAN & JUSTIN BIEBER ANG 01.12.2019 01:19:50 HD 13145 ENKRAT V ZIVLJENJU AVTOMOBILI SLO 01.12.2019 01:24:14 HD 07270 ENGLISHMAN IN NEW YORK STING ANG 01.12.2019 01:28:25 HD 61052 OUTTA MY MIND ZEBRA DOTS ANG 01.12.2019 01:31:50 HD 19168 EVERYBODY HURTS R.E.M.