AML with Myelodysplasia-Related Changes: Development, Challenges, and Treatment Advances

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Prospective, Multicenter, Phase-II Trial of Ibrutinib Plus Venetoclax In

BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance Supplemental material placed on this supplemental material which has been supplied by the author(s) BMJ Open HOVON 141 CLL Version 4, 20 DEC 2018 A prospective, multicenter, phase-II trial of ibrutinib plus venetoclax in patients with creatinine clearance ≥ 30 ml/min who have relapsed or refractory chronic lymphocytic leukemia (RR-CLL) with or without TP53 aberrations HOVON 141 CLL / VIsion Trial of the HOVON and Nordic CLL study groups PROTOCOL Principal Investigator : Arnon P Kater (HOVON) Carsten U Niemann (Nordic CLL study Group)) Sponsor : HOVON EudraCT number : 2016-002599-29 ; Page 1 of 107 Levin M-D, et al. BMJ Open 2020; 10:e039168. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-039168 BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance Supplemental material placed on this supplemental material which has been supplied by the author(s) BMJ Open Levin M-D, et al. BMJ Open 2020; 10:e039168. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-039168 BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance Supplemental material placed on this supplemental material which has been supplied by the author(s) BMJ Open HOVON 141 CLL Version 4, 20 DEC 2018 LOCAL INVESTIGATOR SIGNATURE PAGE Local site name: Signature of Local Investigator Date Printed Name of Local Investigator By my signature, I agree to personally supervise the conduct of this study in my affiliation and to ensure its conduct in compliance with the protocol, informed consent, IRB/EC procedures, the Declaration of Helsinki, ICH Good Clinical Practices guideline, the EU directive Good Clinical Practice (2001-20-EG), and local regulations governing the conduct of clinical studies. -

214120Orig1s000

CENTER FOR DRUG EVALUATION AND RESEARCH APPLICATION NUMBER: 214120Orig1s000 MULTI-DISCIPLINE REVIEW Summary Review Office Director Cross Discipline Team Leader Review Clinical Review Non-Clinical Review Statistical Review Clinical Pharmacology Review NDA Multidisciplinary Review and Evaluation Application Number NDA 214120 Application Type Type 3 Priority or Standard Priority Submit Date 3/3/2020 Received Date 3/3/2020 PDUFA Goal Date 9/3/2020 Office/Division OOD/DHM1 Review Completion Date 9/1/2020 Applicant Celgene Corporation Established Name Azacitidine (Proposed) Trade Name Onureg Pharmacologic Class Nucleoside metabolic inhibitor Formulations Tablet (200 mg, 300 mg) (b) (4) Applicant Proposed Indication/Population Recommendation on Regulatory Regular approval Action Recommended Indication/ For continued treatment of adult patients with acute Population myeloid leukemia who achieved first complete remission (CR) or complete remission with incomplete blood count recovery (CRi) following intensive induction chemotherapy and are not able to complete intensive curative therapy. SNOMED CT for the Recommended 91861009 Indication/Population Recommended Dosing Regimen 300 mg orally daily on Days 1 through 14 of each 28-day cycle Reference ID: 4664570 NDA Multidisciplinary Review and Evaluation NDA 214120 Onureg (azacitidine tablets) TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS ................................................................................................................................... 2 TABLE OF TABLES ....................................................................................................................................... -

The Clinical Management of Chronic Myelomonocytic Leukemia Eric Padron, MD, Rami Komrokji, and Alan F

The Clinical Management of Chronic Myelomonocytic Leukemia Eric Padron, MD, Rami Komrokji, and Alan F. List, MD Dr Padron is an assistant member, Dr Abstract: Chronic myelomonocytic leukemia (CMML) is an Komrokji is an associate member, and Dr aggressive malignancy characterized by peripheral monocytosis List is a senior member in the Department and ineffective hematopoiesis. It has been historically classified of Malignant Hematology at the H. Lee as a subtype of the myelodysplastic syndromes (MDSs) but was Moffitt Cancer Center & Research Institute in Tampa, Florida. recently demonstrated to be a distinct entity with a distinct natu- ral history. Nonetheless, clinical practice guidelines for CMML Address correspondence to: have been inferred from studies designed for MDSs. It is impera- Eric Padron, MD tive that clinicians understand which elements of MDS clinical Assistant Member practice are translatable to CMML, including which evidence has Malignant Hematology been generated from CMML-specific studies and which has not. H. Lee Moffitt Cancer Center & Research Institute This allows for an evidence-based approach to the treatment of 12902 Magnolia Drive CMML and identifies knowledge gaps in need of further study in Tampa, Florida 33612 a disease-specific manner. This review discusses the diagnosis, E-mail: [email protected] prognosis, and treatment of CMML, with the task of divorcing aspects of MDS practice that have not been demonstrated to be applicable to CMML and merging those that have been shown to be clinically similar. Introduction Chronic myelomonocytic leukemia (CMML) is a clonal hemato- logic malignancy characterized by absolute peripheral monocytosis, ineffective hematopoiesis, and an increased risk of transformation to acute myeloid leukemia. -

Philadelphia Chromosome Unmasked As a Secondary Genetic Change in Acute Myeloid Leukemia on Imatinib Treatment

Letters to the Editor 2050 The ELL/MLLT1 dual-color assay described herein entails 3Department of Cytogenetics, City of Hope National Medical Center, Duarte, CA, USA and co-hybridization of probes for the ELL and MLLT1 gene regions, 4 each labeled in a different fluorochrome to allow differentiation Cytogenetics Laboratory, Seattle Cancer Care Alliance, between genes involved in 11q;19p chromosome translocations Seattle, WA, USA E-mail: [email protected] in interphase or metaphase cells. In t(11;19) acute leukemia cases, gain of a signal easily pinpoints the specific translocation breakpoint to either 19p13.1 or 19p13.3 and 11q23. In the References re-evaluation of our own cases in light of the FISH data, the 19p breakpoints were re-assigned in two patients, underscoring a 1 Harrison CJ, Mazzullo H, Cheung KL, Gerrard G, Jalali GR, Mehta A certain degree of difficulty in determining the precise 19p et al. Cytogenetic of multiple myeloma: interpretation of fluorescence in situ hybridization results. Br J Haematol 2003; 120: 944–952. breakpoint in acute leukemia specimens in the context of a 2 Thirman MJ, Levitan DA, Kobayashi H, Simon MC, Rowley JD. clinical cytogenetics laboratory. Furthermore, we speculate that Cloning of ELL, a gene that fuses to MLL in a t(11;19)(q23;p13.1) the ELL/MLLT1 probe set should detect other 19p translocations in acute myeloid leukemia. Proc Natl Acad Sci 1994; 91: 12110– that involve these genes with partners other than MLL. Accurate 12114. molecular classification of leukemia is becoming more im- 3 Tkachuk DC, Kohler S, Cleary ML. -

Intravesical Instillation of Azacitidine Suppresses Tumor Formation Through TNF-R1 and TRAIL-R2 Signaling in Genotoxic Carcinogen-Induced Bladder Cancer

cancers Article Intravesical Instillation of Azacitidine Suppresses Tumor Formation through TNF-R1 and TRAIL-R2 Signaling in Genotoxic Carcinogen-Induced Bladder Cancer Shao-Chuan Wang 1,2,3, Ya-Chuan Chang 2, Min-You Wu 2, Chia-Ying Yu 2, Sung-Lang Chen 1,2,3 and Wen-Wei Sung 1,2,3,* 1 Department of Urology, Chung Shan Medical University Hospital, Taichung 40201, Taiwan; [email protected] (S.-C.W.); [email protected] (S.-L.C.) 2 School of Medicine, Chung Shan Medical University, Taichung 40201, Taiwan; [email protected] (Y.-C.C.); [email protected] (M.-Y.W.); [email protected] (C.-Y.Y.) 3 Institute of Medicine, Chung Shan Medical University, Taichung 40201, Taiwan * Correspondence: [email protected] or fl[email protected]; Tel.: +886-4-2473-9595 Simple Summary: Approximately 70% of all bladder cancer is diagnosed as non-muscle invasive bladder cancer and can be treated by transurethral resection of the bladder tumor, followed by intravesical instillation chemotherapy. Bacille Calmette-Guérin (BCG) is the first-line agent for intravesical instillation, but its accessibility has been limited for years due to a BCG shortage. Here, our aim was to evaluate the therapeutic role of intravesical instillation of azacitidine, a DNA methyltransferase inhibitor, in bladder cancer. Cell model experiments showed that azacitidine inhibited TNFR1 downstream pathways to downregulate HIF-1α, claspin, and survivin. Concomitant Citation: Wang, S.-C.; Chang, Y.-C.; upregulation of the TRAIL R2 pathway by azacitidine ultimately drove the tumor cells to apoptosis. Wu, M.-Y.; Yu, C.-Y.; Chen, S.-L.; Sung, Rats with genotoxic carcinogen-induced bladder cancer showed a significantly reduced in vivo tumor W.-W. -

The New Therapeutic Strategies in Pediatric T-Cell Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia

International Journal of Molecular Sciences Review The New Therapeutic Strategies in Pediatric T-Cell Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia Marta Weronika Lato 1 , Anna Przysucha 1, Sylwia Grosman 1, Joanna Zawitkowska 2 and Monika Lejman 3,* 1 Student Scientific Society, Laboratory of Genetic Diagnostics, Medical University of Lublin, 20-093 Lublin, Poland; [email protected] (M.W.L.); [email protected] (A.P.); [email protected] (S.G.) 2 Department of Pediatric Hematology, Oncology and Transplantology, Medical University of Lublin, 20-093 Lublin, Poland; [email protected] 3 Laboratory of Genetic Diagnostics, Medical University of Lublin, 20-093 Lublin, Poland * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: Childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia is a genetically heterogeneous cancer that ac- counts for 10–15% of T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (T-ALL) cases. The T-ALL event-free survival rate (EFS) is 85%. The evaluation of structural and numerical chromosomal changes is important for a comprehensive biological characterization of T-ALL, but there are currently no ge- netic prognostic markers. Despite chemotherapy regimens, steroids, and allogeneic transplantation, relapse is the main problem in children with T-ALL. Due to the development of high-throughput molecular methods, the ability to define subgroups of T-ALL has significantly improved in the last few years. The profiling of the gene expression of T-ALL has led to the identification of T-ALL subgroups, and it is important in determining prognostic factors and choosing an appropriate treatment. Novel therapies targeting molecular aberrations offer promise in achieving better first remission with the Citation: Lato, M.W.; Przysucha, A.; hope of preventing relapse. -

LEUKEMIA CHEMOTHERAPY REGIMENS (Part 1 of 2) the Selection, Dosing, and Administration of Anti-Cancer Agents and the Management of Associated Toxicities Are Complex

LEUKEMIA CHEMOTHERAPY REGIMENS (Part 1 of 2) The selection, dosing, and administration of anti-cancer agents and the management of associated toxicities are complex. Drug dose modifications and schedule and initiation of supportive care interventions are often necessary because of expected toxicities and because of individual patient variability, prior treatment, and comorbidities. Thus, the optimal delivery of anti-cancer agents requires a healthcare delivery team experienced in the use of such agents and the management of associated toxicities in patients with cancer. The chemotherapy regimens below may include both FDA-approved and unapproved uses/regimens and are provided as references only to the latest treatment strategies. Clinicians must choose and verify treatment options based on the individual patient. REGIMEN DOSING Acute Myeloid Leukemia (AML) Induction Therapy Cytarabine (Cytosar-U; ARA-C) + Days 1–3: An anthracycline (eg, daunorubicin at least 60mg/m2/day IV, an anthracycline idarubicin 10–12mg/m2/day IV, or mitoxantrone 10–12mg/m2/day IV), plus (daunorubicin [Cerubidine], Days 1–7: Cytarabine 100–200mg/m2/day continuous IV infusion. idarubicin [Idamycin], OR mitoxantrone [Novantrone])1, 2 Days 1–3: An anthracycline (eg, daunorubicin 45mg/m2/day IV, idarubicin 12mg/m2/day IV, or mitoxantrone 12mg/m2/day IV), plus Days 1–7: Cytarabine 100mg/m2/day continuous IV infusion. Intermediate-dose cytarabine3 Cycle 1 Days 1–7: Cytarabine 200mg/m2/day continuous IV infusion, plus Days 5–6: Idarubicin 12mg/m2/day IV. Cycle 2 Days 1–6: Cytarabine 1,000mg/m2 continuous IV infusion for 3 hrs twice daily, plus Days 3, 5 and 7: Amsacrine 120mg/m2/day. -

Acute Myeloid Leukemia Evolving from JAK 2-Positive Primary Myelofibrosis and Concomitant CD5-Negative Mantle Cell

Hindawi Publishing Corporation Case Reports in Hematology Volume 2012, Article ID 875039, 6 pages doi:10.1155/2012/875039 Case Report Acute Myeloid Leukemia Evolving from JAK 2-Positive Primary Myelofibrosis and Concomitant CD5-Negative Mantle Cell Lymphoma: A Case Report and Review of the Literature Diana O. Treaba,1 Salwa Khedr,1 Shamlal Mangray,1 Cynthia Jackson,1 Jorge J. Castillo,2 and Eric S. Winer2 1 Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, Rhode Island Hospital, The Warren Alpert Medical School, Brown University, Providence, RI 02903, USA 2 Division of Hematology/Oncology, The Miriam Hospital, The Warren Alpert Medical School, Brown University, Providence, RI 02904, USA Correspondence should be addressed to Diana O. Treaba, [email protected] Received 2 April 2012; Accepted 21 June 2012 Academic Editors: E. Arellano-Rodrigo, G. Damaj, and M. Gentile Copyright © 2012 Diana O. Treaba et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Primary myelofibrosis (formerly known as chronic idiopathic myelofibrosis), has the lowest incidence amongst the chronic myeloproliferative neoplasms and is characterized by a rather short median survival and a risk of progression to acute myeloid leukemia (AML) noted in a small subset of the cases, usually as a terminal event. As observed with other chronic myeloproliferative neoplasms, the bone marrow biopsy may harbor small lymphoid aggregates, often assumed reactive in nature. In our paper, we present a 70-year-old Caucasian male who was diagnosed with primary myelofibrosis, and after 8 years of followup and therapy developed an AML. -

Vidaza, INN-Azacitidine

ANNEX I SUMMARY OF PRODUCT CHARACTERISTICS 1 1. NAME OF THE MEDICINAL PRODUCT Vidaza 25 mg/ml powder for suspension for injection 2. QUALITATIVE AND QUANTITATIVE COMPOSITION Each vial contains 100 mg azacitidine. After reconstitution, each ml suspension contains 25 mg azacitidine. For a full list of excipients, see section 6.1. 3. PHARMACEUTICAL FORM Powder for suspension for injection. White lyophilised powder. 4. CLINICAL PARTICULARS 4.1 Therapeutic indications Vidaza is indicated for the treatment of adult patients who are not eligible for haematopoietic stem cell transplantation with: • intermediate-2 and high-risk myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS) according to the International Prognostic Scoring System (IPSS), • chronic myelomonocytic leukaemia (CMML) with 10-29 % marrow blasts without myeloproliferative disorder, • acute myeloid leukaemia (AML) with 20-30 % blasts and multi-lineage dysplasia, according to World Health Organisation (WHO) classification. 4.2 Posology and method of administration Vidaza treatment should be initiated and monitored under the supervision of a physician experienced in the use of chemotherapeutic agents. Patients should be premedicated with anti-emetics for nausea and vomiting. Posology The recommended starting dose for the first treatment cycle, for all patients regardless of baseline haematology laboratory values, is 75 mg/m2 of body surface area, injected subcutaneously, daily for 7 days, followed by a rest period of 21 days (28-day treatment cycle). It is recommended that patients be treated for a minimum of 6 cycles. Treatment should be continued as long as the patient continues to benefit or until disease progression. Patients should be monitored for haematologic response/toxicity and renal toxicities (see section 4.4); a delay in starting the next cycle or a dose reduction as described below may be necessary. -

Draft Matrix Post Referral PDF 189 KB

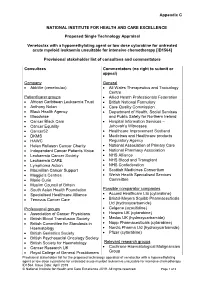

Appendix C NATIONAL INSTITUTE FOR HEALTH AND CARE EXCELLENCE Proposed Single Technology Appraisal Venetoclax with a hypomethylating agent or low dose cytarabine for untreated acute myeloid leukaemia unsuitable for intensive chemotherapy [ID1564] Provisional stakeholder list of consultees and commentators Consultees Commentators (no right to submit or appeal) Company General • AbbVie (venetoclax) • All Wales Therapeutics and Toxicology Centre Patient/carer groups • Allied Health Professionals Federation • African Caribbean Leukaemia Trust • British National Formulary • Anthony Nolan • Care Quality Commission • Black Health Agency • Department of Health, Social Services • Bloodwise and Public Safety for Northern Ireland • Cancer Black Care • Hospital Information Services – • Cancer Equality Jehovah’s Witnesses • Cancer52 • Healthcare Improvement Scotland • DKMS • Medicines and Healthcare products • HAWC Regulatory Agency • Helen Rollason Cancer Charity • National Association of Primary Care • Independent Cancer Patients Voice • National Pharmacy Association • Leukaemia Cancer Society • NHS Alliance • Leukaemia CARE • NHS Blood and Transplant • Lymphoma Action • NHS Confederation • Macmillan Cancer Support • Scottish Medicines Consortium • Maggie’s Centres • Welsh Health Specialised Services • Marie Curie Committee • Muslim Council of Britain • South Asian Health Foundation Possible comparator companies • Specialised Healthcare Alliance • Accord Healthcare Ltd (cytarabine) • Tenovus Cancer Care • Bristol-Meyers Squibb Pharmaceuticals Ltd -

A Novel CDK9 Inhibitor Increases the Efficacy of Venetoclax (ABT-199) in Multiple Models of Hematologic Malignancies

Leukemia (2020) 34:1646–1657 https://doi.org/10.1038/s41375-019-0652-0 ARTICLE Molecular targets for therapy A novel CDK9 inhibitor increases the efficacy of venetoclax (ABT-199) in multiple models of hematologic malignancies 1 1 2,3 4 1 5 6 Darren C. Phillips ● Sha Jin ● Gareth P. Gregory ● Qi Zhang ● John Xue ● Xiaoxian Zhao ● Jun Chen ● 1 1 1 1 1 1 Yunsong Tong ● Haichao Zhang ● Morey Smith ● Stephen K. Tahir ● Rick F. Clark ● Thomas D. Penning ● 2,7 3 5 1 4 2,7 Jennifer R. Devlin ● Jake Shortt ● Eric D. Hsi ● Daniel H. Albert ● Marina Konopleva ● Ricky W. Johnstone ● 8 1 Joel D. Leverson ● Andrew J. Souers Received: 27 November 2018 / Revised: 18 October 2019 / Accepted: 13 November 2019 / Published online: 11 December 2019 © The Author(s) 2019 Abstract MCL-1 is one of the most frequently amplified genes in cancer, facilitating tumor initiation and maintenance and enabling resistance to anti-tumorigenic agents including the BCL-2 selective inhibitor venetoclax. The expression of MCL-1 is maintained via P-TEFb-mediated transcription, where the kinase CDK9 is a critical component. Consequently, we developed a series of potent small-molecule inhibitors of CDK9, exemplified by the orally active A-1592668, with CDK selectivity profiles 1234567890();,: 1234567890();,: that are distinct from related molecules that have been extensively studied clinically. Short-term treatment with A-1592668 rapidly downregulates RNA pol-II (Ser 2) phosphorylation resulting in the loss of MCL-1 protein and apoptosis in MCL-1- dependent hematologic tumor cell lines. This cell death could be attenuated by either inhibiting caspases or overexpressing BCL-2 protein. -

The AML Guide Information for Patients and Caregivers Acute Myeloid Leukemia

The AML Guide Information for Patients and Caregivers Acute Myeloid Leukemia Emily, AML survivor Revised 2012 Inside Front Cover A Message from Louis J. DeGennaro, PhD President and CEO of The Leukemia & Lymphoma Society The Leukemia & Lymphoma Society (LLS) wants to bring you the most up-to-date blood cancer information. We know how important it is for you to understand your treatment and support options. With this knowledge, you can work with members of your healthcare team to move forward with the hope of remission and recovery. Our vision is that one day most people who have been diagnosed with acute myeloid leukemia (AML) will be cured or will be able to manage their disease and have a good quality of life. We hope that the information in this Guide will help you along your journey. LLS is the world’s largest voluntary health organization dedicated to funding blood cancer research, advocacy and patient services. Since the first funding in 1954, LLS has invested more than $814 million in research specifically targeting blood cancers. We will continue to invest in research for cures and in programs and services that improve the quality of life for people who have AML and their families. We wish you well. Louis J. DeGennaro, PhD President and Chief Executive Officer The Leukemia & Lymphoma Society Inside This Guide 2 Introduction 3 Here to Help 6 Part 1—Understanding AML About Marrow, Blood and Blood Cells About AML Diagnosis Types of AML 11 Part 2—Treatment Choosing a Specialist Ask Your Doctor Treatment Planning About AML Treatments Relapsed or Refractory AML Stem Cell Transplantation Acute Promyelocytic Leukemia (APL) Treatment Acute Monocytic Leukemia Treatment AML Treatment in Children AML Treatment in Older Patients 24 Part 3—About Clinical Trials 25 Part 4—Side Effects and Follow-Up Care Side Effects of AML Treatment Long-Term and Late Effects Follow-up Care Tracking Your AML Tests 30 Take Care of Yourself 31 Medical Terms This LLS Guide about AML is for information only.