Examining Employer Liability for the Crimes and Bad Acts of Employees

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Emotion, Seduction and Intimacy: Alternative Perspectives on Human Behaviour RIDLEY-DUFF, R

Emotion, seduction and intimacy: alternative perspectives on human behaviour RIDLEY-DUFF, R. J. Available from Sheffield Hallam University Research Archive (SHURA) at: http://shura.shu.ac.uk/2619/ This document is the author deposited version. You are advised to consult the publisher's version if you wish to cite from it. Published version RIDLEY-DUFF, R. J. (2010). Emotion, seduction and intimacy: alternative perspectives on human behaviour. Silent Revolution Series . Seattle, Libertary Editions. Repository use policy Copyright © and Moral Rights for the papers on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. Users may download and/or print one copy of any article(s) in SHURA to facilitate their private study or for non- commercial research. You may not engage in further distribution of the material or use it for any profit-making activities or any commercial gain. Sheffield Hallam University Research Archive http://shura.shu.ac.uk Silent Revolution Series Emotion Seduction & Intimacy Alternative Perspectives on Human Behaviour Third Edition © Dr Rory Ridley-Duff, 2010 Edited by Dr Poonam Thapa Libertary Editions Seattle © Dr Rory Ridley‐Duff, 2010 Rory Ridley‐Duff has asserted his right to be identified as the author of this work in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Acts 1988. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution‐Noncommercial‐No Derivative Works 3.0 Unported License. Attribution — You must attribute the work in the manner specified by the author or licensor (but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work). Noncommercial — You may not use this work for commercial purposes. -

The Seduction of Innocence: the Attraction and Limitations of the Focus on Innocence in Capital Punishment Law and Advocacy

Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology Volume 95 Article 7 Issue 2 Winter Winter 2005 The educS tion of Innocence: The Attraction and Limitations of the Focus on Innocence in Capital Punishment Law and Advocacy Carol S. Steiker Jordan M. Steiker Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.northwestern.edu/jclc Part of the Criminal Law Commons, Criminology Commons, and the Criminology and Criminal Justice Commons Recommended Citation Carol S. Steiker, Jordan M. Steiker, The eS duction of Innocence: The ttrA action and Limitations of the Focus on Innocence in Capital Punishment Law and Advocacy, 95 J. Crim. L. & Criminology 587 (2004-2005) This Symposium is brought to you for free and open access by Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology by an authorized editor of Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. 0091-41 69/05/9502-0587 THE JOURNAL OF CRIMINAL LAW & CRIMINOLOGY Vol. 95, No. 2 Copyright 0 2005 by Northwestern University, School of Law Printed in US.A. THE SEDUCTION OF INNOCENCE: THE ATTRACTION AND LIMITATIONS OF THE FOCUS ON INNOCENCE IN CAPITAL PUNISHMENT LAW AND ADVOCACY CAROL S. STEIKER"& JORDAN M. STEIKER** INTRODUCTION Over the past five years we have seen an unprecedented swell of debate at all levels of public life regarding the American death penalty. Much of the debate centers on the crisis of confidence engendered by the high-profile release of a significant number of wrongly convicted inmates from the nation's death rows. Advocates for reform or abolition of capital punishment have seized upon this issue to promote various public policy initiatives to address the crisis, including proposals for more complete DNA collection and testing, procedural reforms in capital cases, substantive limits on the use of capital punishment, suspension of executions, and outright abolition. -

The Boundaries of Vicarious Liability: an Economic Analysis of the Scope of Employment Rule and Related Legal Doctrines

University of Chicago Law School Chicago Unbound Journal Articles Faculty Scholarship 1987 The Boundaries of Vicarious Liability: An Economic Analysis of the Scope of Employment Rule and Related Legal Doctrines Alan O. Sykes Follow this and additional works at: https://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/journal_articles Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Alan O. Sykes, "The Boundaries of Vicarious Liability: An Economic Analysis of the Scope of Employment Rule and Related Legal Doctrines," 101 Harvard Law Review 563 (1987). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at Chicago Unbound. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal Articles by an authorized administrator of Chicago Unbound. For more information, please contact [email protected]. VOLUME 101 JANUARY 1988 NUMBER 3 HARVARD LAW REVIEW1 ARTICLES THE BOUNDARIES OF VICARIOUS LIABILITY: AN ECONOMIC ANALYSIS OF THE SCOPE OF EMPLOYMENT RULE AND RELATED LEGAL DOCTRINES Alan 0. Sykes* 441TICARIOUS liability" may be defined as the imposition of lia- V bility upon one party for a wrong committed by another party.1 One of its most common forms is the imposition of liability on an employer for the wrong of an employee or agent. The imposition of vicarious liability usually depends in part upon the nature of the activity in which the wrong arises. For example, if an employee (or "servant") commits a tort within the ordinary course of business, the employer (or "master") normally incurs vicarious lia- bility under principles of respondeat superior. If the tort arises outside the "scope of employment," however, the employer does not incur liability, absent special circumstances. -

Around Frolic and Detour, a Persistent Problem on the Highway of Torts William A

Campbell Law Review Volume 19 Article 4 Issue 1 Fall 1996 January 1996 Automobile Insurance Policies Build "Write-Away" Around Frolic and Detour, a Persistent Problem on the Highway of Torts William A. Wines Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.campbell.edu/clr Part of the Insurance Law Commons Recommended Citation William A. Wines, Automobile Insurance Policies Build "Write-Away" Around Frolic and Detour, a Persistent Problem on the Highway of Torts, 19 Campbell L. Rev. 85 (1996). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarly Repository @ Campbell University School of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Campbell Law Review by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Repository @ Campbell University School of Law. Wines: Automobile Insurance Policies Build "Write-Away" Around Frolic an AUTOMOBILE INSURANCE POLICIES BUILD "WRITE-AWAY" AROUND FROLIC AND DETOUR, A PERSISTENT PROBLEM ON THE HIGHWAY OF TORTS WILLIAM A. WINESt Historians trace the origin of the doctrine of frolic and detour to the pronouncement of Baron Parke in 1834.1 The debate over the wisdom and the theoretical underpinnings of the doctrine seems to have erupted not long after the birth of the doctrine. No less a scholar than Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr., questioned whether the doctrine was contrary to common sense.2 This doc- trine continued to attract legal scholars who were still debating the underlying policy premises as the doctrine celebrated its ses- quicentennial and headed toward the second century mark.3 However, the main source of cases which test the doctrine, namely automobile accidents, has started to decline, at least insofar as it involves "frolic and detour" questions and thus the impact of this doctrine may becoming minimized.4 t William A. -

Vicarious Liability

STATE OF FLORIDA TRANSPORTATION COMPENDIUM OF LAW Kurt M. Spengler Wicker, Smith, O’Hara, McCoy & Ford, P.A. 390 N. Orange Ave., Suite 1000 Orlando, FL 32802 Tel: (407) 843‐3939 Email: [email protected] www.wickersmith.com Christopher Barkas Carr Allison 305 S. Gadsden Street Tallahassee, FL 32301 Tel: (850) 222‐2107 Email: [email protected] L. Johnson Sarber III Marks Gray, P.A. 1200 Riverplace Boulevard, Suite 800 Jacksonville, FL 32207 Tel: (904) 398‐0900 Email: [email protected] www.marksgray.com A. Elements of Proof for the Derivative Negligence Claims of Negligent Entrustment, Hiring/Retention and Supervision 1. Respondeat Superior a. What are the elements necessary to establish liability under a theory of Respondeat Superior? Under Florida law, an employer is only vicariously liable for an employee's acts if the employee was acting to further the employer's interest through the scope of the employee’s employment at the time of the incident. An employee acts within the scope of his employment only if (1) his act is of the kind he is required to perform, (2) it occurs substantially within the time and space limits of employment, and (3) is activated at least in part by a purpose to serve the master. Kane Furniture Corp. v. Miranda, 506 So.2d 1061 (Fla. 2d DCA 1987). Additionally, once an employee deviates from the scope of his employment, he may return to that employment only by doing something which meaningfully benefits his employer's interests. Borrough’s Corp. v. American Druggists’ Insur. Co., 450 So.2d 540 (Fla. -

![2019-Ohio-3745.]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1630/2019-ohio-3745-501630.webp)

2019-Ohio-3745.]

[Cite as Rieger v. Giant Eagle, Inc., 157 Ohio St.3d 512, 2019-Ohio-3745.] RIEGER, APPELLEE, v. GIANT EAGLE, INC., APPELLANT. [Cite as Rieger v. Giant Eagle, Inc., 157 Ohio St.3d 512, 2019-Ohio-3745.] Civil law—Application of Civ.R. 50(A)(4)—Directed verdict should be granted when there is insufficient evidence as a matter of law establishing causation for claims of negligence and negligent entrustment—Court of appeals’ judgment reversed. (No. 2018-0883—Submitted April 24, 2019—Decided September 19, 2019.) APPEAL from the Court of Appeals for Cuyahoga County, No. 105714, 2018-Ohio-1837. _________________ STEWART, J. {¶ 1} This is a discretionary appeal from the Eighth District Court of Appeals challenging a jury verdict awarding compensatory and punitive damages on claims of negligence and negligent entrustment against appellant, Giant Eagle, Inc. Because there is insufficient evidence as a matter of law to establish causation for purposes of those claims, the court of appeals should have reversed the trial court’s denial of Giant Eagle’s Civ.R. 50(A)(4) motion for a directed verdict. Accordingly, we reverse the judgment of the court of appeals and enter judgment in favor of Giant Eagle. I. FACTS AND PROCEDURAL HISTORY {¶ 2} In December 2012, appellee, Barbara Rieger,1 was at the Giant Eagle grocery store in Brook Park. While she was standing at the bakery counter, her shopping cart was hit by a Giant Eagle motorized cart driven by Ruth Kurka. As a result of the collision, Rieger was knocked to the ground and injured. Rieger was 1. -

Employer Liability for Employee Actions: Derivative Negligence Claims in New Mexico Timothy C. Holm Matthew W. Park Modrall, Sp

Employer Liability for Employee Actions: Derivative Negligence Claims in New Mexico Timothy C. Holm Matthew W. Park Modrall, Sperling, Roehl, Harris & Sisk, P.A. Post Office Box 2168 Bank of America Centre 500 Fourth Street NW, Suite 1000 Albuquerque, New Mexico 87103-2168 Telephone: 505.848.1800 Email: [email protected] Every employer is concerned about potential liability for the tortious actions of its employees. Simply stated: Where does an employer’s responsibility for its employee’s actions end, the employee’s personal responsibility begin, and to what extent does accountability overlap? This article is intended to detail the various derivative negligence claims recognized in New Mexico that may impute liability to an employer for its employee’s actions, the elements of each claim, and possible defenses. This subject matter is of particular importance to New Mexico employers generally and transportation employers specifically. A. Elements of Proof for the Derivative Negligent Claim of Negligent Entrustment, Hiring/Retention and Supervision In New Mexico, there are four distinct theories by which an employer might be held to have derivative or dependent liability for the conduct of an employee.1 The definition of derivative or dependent liability is that the employer can be held liable for the fault of the employee in causing to a third party. 1. Respondeat Superior a. What are the elements necessary to establish liability under a theory of Respondeat Superior? An employer is responsible for injury to a third party when its employee commits negligence while acting within the course and scope of his or employment. See McCauley v. -

Negligent Entrustment

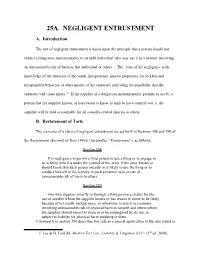

25A. NEGLIGENT ENTRUSTMENT A. Introduction The tort of negligent entrustment is based upon the principle that a person should not entrust a dangerous instrumentality to an unfit individual who may use it in a manner involving an unreasonable risk of harm to that individual or others. The “crux of the negligence is the knowledge of the entrustor of the youth, inexperience, known propensity for reckless and irresponsible behavior, or other quality of the entrustee, indicating the possibility that the entrustee will cause injury.”1 If the supplier of a dangerous instrumentality permits its use by a person that the supplier knows, or has reason to know, is unfit to have control over it, the supplier will be held accountable for all causally-related injuries to others. B. Restatement of Torts The elements of a claim of negligent entrustment are set forth in Sections 308 and 390 of the Restatement (Second) of Torts (1965) (hereinafter “Restatement”), as follows: Section 308 It is negligence to permit a third person to use a thing or to engage in an activity which is under the control of the actor, if the actor knows or should know that such person intends or is likely to use the thing or to conduct himself in the activity in such a manner as to create an unreasonable risk of harm to others. Section 390 One who supplies directly or through a third person a chattel for the use of another whom the supplier knows or has reason to know to be likely because of his youth, inexperience, or otherwise, to use it in a manner involving unreasonable risk of physical harm to himself and others whom the supplier should expect to share in or be endangered by its use, is subject to liability for physical harm resulting to them. -

Alienation of Affection Suits in Connecticut a Guide to Resources in the Law Library

Connecticut Judicial Branch Law Libraries Copyright © 2006-2020, Judicial Branch, State of Connecticut. All rights reserved. 2020 Edition Alienation of Affection Suits in Connecticut A Guide to Resources in the Law Library This guide is no longer being updated on a regular basis. But we make it available for the historical significance in the development of the law. Table of Contents Introduction .................................................................................................... 3 Section 1: Spousal Alienation of Affection ............................................................ 4 Table 1: Spousal Alienation of Affections in Other States ....................................... 8 Table 2: Brown v. Strum ................................................................................... 9 Section 2: Criminal Conversation ..................................................................... 11 Table 3: Criminal Conversation in Other States .................................................. 14 Section 3: Alienation of Affection of Parent or Child ............................................ 15 Table 4: Intentional Infliction of Emotional Distress ............................................ 18 Table 5: Campos v. Coleman ........................................................................... 20 Prepared by Connecticut Judicial Branch, Superior Court Operations, Judge Support Services, Law Library Services Unit [email protected] Alienation-1 These guides are provided with the understanding that they represent -

Injury to Passengers and Visitors

(intro Son of a Son of a Sailor): 35 (voice of John Hughes Cooper): Good morning to Captain and crew alike and welcome to the Admiralty Docket. This is John Hughes Cooper with a glimpse into your rights and responsibilities at sea and upon the navigable waters. Today our subject is Shipboard Injury to Passengers and Visitors. A person who contracts to travel aboard a vessel in exchange for payment of a fare, is called a passenger. Other than passengers and seamen, a person aboard a vessel with the consent of her owner is called a visitor, whether aboard for business or pleasure. Historically, the general maritime law imposed upon vessel owners a very high duty of care to protect passengers from injury or death aboard a vessel, but imposed a lesser duty of care to protect visitors while aboard. In many cases this distinction was based upon common law real property concepts of invitees and licensees and was said to flow from the greater benefits to the vessel owners from the presence of fare paying passengers as compared to lesser benefits to the vessel owners from the presence of non paying visitors. However, this landside distinction was abandoned by the U. S. Supreme Court in the 1959 case, Kermarec v. Compagnie Gererale TransatlantigUe, which requires vessel owners to exercise reasonable care to protect from injury or death all non-crewmembers lawfully aboard a vessel, whether passengers or visitors. Generally, this means that passengers and visitors are entitled to safe means of boarding the vessel, safe facilities aboard the vessel, and compliance with all applicable safety standards and regulations. -

Institutional Liability for Employees' Intentional Torts

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by ValpoScholar Valparaiso University Law Review Volume 53 Number 1 pp.1-45 Institutional Liability for Employees’ Intentional Torts: Vicarious Liability as a Quasi-Substitute for Punitive Damages Catherine M. Sharkey Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.valpo.edu/vulr Part of the Torts Commons Recommended Citation Catherine M. Sharkey, Institutional Liability for Employees’ Intentional Torts: Vicarious Liability as a Quasi- Substitute for Punitive Damages, 53 Val. U. L. Rev. 1 (). Available at: https://scholar.valpo.edu/vulr/vol53/iss1/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Valparaiso University Law School at ValpoScholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Valparaiso University Law Review by an authorized administrator of ValpoScholar. For more information, please contact a ValpoScholar staff member at [email protected]. Sharkey: Institutional Liability for Employees’ Intentional Torts: Vicario Articles INSTITUTIONAL LIABILITY FOR EMPLOYEES’ INTENTIONAL TORTS: VICARIOUS LIABILITY AS A QUASI-SUBSTITUTE FOR PUNITIVE DAMAGES Catherine M. Sharkey* Abstract Modern day vicarious liability cases often address the liability of enterprises and institutions whose agents have committed intentional acts. Increasingly, when employers are sued, the line is blurred between the principal’s vicarious liability for its agent’s acts and its own direct liability for hiring and/or failing to supervise or control its agent. From an economic deterrence perspective, the imposition of vicarious liability induces employers to adopt cost-justified preventative measures, including selective hiring and more stringent supervision and discipline, and, in some instances, to truncate the scope of their business activities. -

On Curiosity: the Art of Market Seduction

MATTERING PRESS Mattering Press is an academic-led Open Access publisher that operates on a not-for-profit basis as a UK registered charity. It is committed to developing new publishing models that can widen the constituency of academic knowledge and provide authors with significant levels of support and feedback. All books are available to download for free or to purchase as hard copies. More at matteringpress.org. The Press’s work has been supported by: Centre for Invention and Social Process (Goldsmiths, University of London), Centre for Mobilities Research (Lancaster University), European Association for the Study of Science and Technology, Hybrid Publishing Lab, infostreams, Institute for Social Futures (Lancaster University), Open Humanities Press, and Tetragon. Making this book Mattering Press is keen to render more visible the unseen processes that go into the production of books. We would like to thank Joe Deville, who acted as the Press’s coordinating editor for this book, Jenn Tomomitsu for the copy-editing, Tetragon for the production and typesetting, Sarah Terry for the proofreading, and Ed Akerboom at infostreams for the website design. Cover Mattering Press thanks Łukasz Dziedzic for Lato, our incomparable cover typeface. It remains one of the best free typefaces available and is released by his foundry tyPoland under the free, libre and open source Open Font License. Cover art by Julien McHardy. ON CURIOSITY The Art of Market Seduction FRANCK COCHOY TRANslated bY JaciARA T. liRA Originally published as De la curiosité: L’art de la séduction marchande © Armand Colin, 2011. This translation © Franck Cochoy, 2016. First published by Mattering Press, Manchester.