A Performance Guide to Áskell Másson's Marimba Concerto

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

College Orchestra Director Programming Decisions Regarding Classical Twentieth-Century Music Mark D

James Madison University JMU Scholarly Commons Dissertations The Graduate School Summer 2017 College orchestra director programming decisions regarding classical twentieth-century music Mark D. Taylor James Madison University Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.lib.jmu.edu/diss201019 Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons Recommended Citation Taylor, Mark D., "College orchestra director programming decisions regarding classical twentieth-century music" (2017). Dissertations. 132. https://commons.lib.jmu.edu/diss201019/132 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the The Graduate School at JMU Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of JMU Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. College Orchestra Director Programming Decisions Regarding Classical Twentieth-Century Music Mark David Taylor A Doctor of Musical Arts Document submitted to the Graduate Faculty of JAMES MADISON UNIVERSITY In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts School of Music August 2017 FACULTY COMMITTEE Committee Chair: Dr. Eric Guinivan Committee Members/ Readers: Dr. Mary Jean Speare Mr. Foster Beyers Acknowledgments Dr. Robert McCashin, former Director of Orchestras and Professor of Orchestral Conducting at James Madison University (JMU) as well as a co-founder of College Orchestra Directors Association (CODA), served as an important sounding-board as the study emerged. Dr. McCashin was particularly helpful in pointing out the challenges of undertaking such a study. I would have been delighted to have Dr. McCashin serve as the chair of my doctoral committee, but he retired from JMU before my study was completed. -

Programnotes Brahms Double

Please note that osmo Vänskä replaces Bernard Haitink, who has been forced to cancel his appearance at these concerts. Program One HundRed TwenTy-SeCOnd SeASOn Chicago symphony orchestra riccardo muti Music director Pierre Boulez Helen Regenstein Conductor emeritus Yo-Yo ma Judson and Joyce Green Creative Consultant Global Sponsor of the CSO Thursday, October 18, 2012, at 8:00 Friday, October 19, 2012, at 8:00 Saturday, October 20, 2012, at 8:00 osmo Vänskä Conductor renaud Capuçon Violin gautier Capuçon Cello music by Johannes Brahms Concerto for Violin and Cello in A Minor, Op. 102 (Double) Allegro Andante Vivace non troppo RenAud CApuçOn GAuTieR CApuçOn IntermIssIon Symphony no. 1 in C Minor, Op. 68 un poco sostenuto—Allegro Andante sostenuto un poco allegretto e grazioso Adagio—Allegro non troppo, ma con brio This program is partially supported by grants from the Illinois Arts Council, a state agency, and the National Endowment for the Arts. Comments by PhilliP huscher Johannes Brahms Born May 7, 1833, Hamburg, Germany. Died April 3, 1897, Vienna, Austria. Concerto for Violin and Cello in a minor, op. 102 (Double) or Brahms, the year 1887 his final orchestral composition, Flaunched a period of tying up this concerto for violin and cello— loose ends, finishing business, and or the Double Concerto, as it would clearing his desk. He began by ask- soon be known. Brahms privately ing Clara Schumann, with whom decided to quit composing for he had long shared his most inti- good, and in 1890 he wrote to his mate thoughts, to return all the let- publisher Fritz Simrock that he had ters he had written to her over the thrown “a lot of torn-up manuscript years. -

The Italian Double Concerto: a Study of the Italian Double Concerto for Trumpet at the Basilica of San Petronio in Bologna, Italy

The Italian Double Concerto: A study of the Italian Double Concerto for Trumpet at the Basilica of San Petronio in Bologna, Italy a document submitted to the Division of Research and Advanced Studies of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts Performance Studies Division – The University of Cincinnati College-Conservatory of Music 2013 by Jason A. Orsen M.M., Kent State University, 2003 B.M., S.U.N.Y Fredonia, 2001 Committee Chair: Dr. Vivian Montgomery Prof. Alan Siebert Dr. Mark Ostoich © 2013 Jason A. Orsen All Rights Reserved 2 Table of Contents Chapter I. Introduction: The Italian Double Concerto………………………………………5 II. The Basilica of San Petronio……………………………………………………11 III. Maestri di Cappella at San Petronio…………………………………………….18 IV. Composers and musicians at San Petronio……………………………………...29 V. Italian Double Concerto…………………………………………………………34 VI. Performance practice issues……………………………………………………..37 Bibliography……………………………………………………………………………………..48 3 Outline I. Introduction: The Italian Double Concerto A. Background of Bologna, Italy B. Italian Baroque II. The Basilica of San Petronio A. Background information on the church B. Explanation of physical dimensions, interior and effect it had on a composer’s style III. Maestri di Cappella at San Petronio A. Maurizio Cazzati B. Giovanni Paolo Colonna C. Giacomo Antonio Perti IV. Composers and musicians at San Petronio A. Giuseppe Torelli B. Petronio Franceschini C. Francesco Onofrio Manfredini V. Italian Double Concerto A. Description of style and use B. Harmonic and compositional tendencies C. Compare and contrast with other double concerti D. Progression and development VI. Performance practice issues A. Ornamentation B. Orchestration 4 I. -

Vivaldi Piccolo Concerto in C Bolling, Claude Flute Sentimentale Briccialli Flute Carnival of Venice Chaminade, C

Composer Instrument Title DeMare Piccolo LaTourterelle (The Wren) Vivaldi Piccolo Concerto in C Bolling, Claude Flute Sentimentale Briccialli Flute Carnival of Venice Chaminade, C. Flute Concertino Griffis, Charles Flute Poem Kennan, Kent Flute Night Soliloguy Mozart, W.A. Flute Concerto, No.1 Mozart, W.A. Flute Concerto, No 2 Telemann Flute Suite in a minor Corelli Oboe Concereto Haydn, F.J. Oboe Concerto von Weber Oboe Concertino Mozart, W.A. Oboe Concerto in Eb-Rondo Vivaldi Oboe Concerto Mozart, W.A. Bassoon Concert #, KV 191 Mozart, W.A. Bassoon Concert #2 Phillips, Burrill Bassoon Concert Piece Senaille/Wright Bassoon Intro-AllegroSpiritoso von Weber Bassoon Andante e Rondo Ungarese Foot Bassoon Grandfathers Clock Wenzel Johann Bassoon Variations and Rondo Bencriscutto,Frank Clarinet Concertino for Clarinet and Band Bergson Clarinet Scene and Air Cavallini Clarinet Adagio Tarentella Messenger Clarinet Solo de Concours Rabaud Clarinet Solo de Concours Rimsky-Korsakov Clarinet Concert Rossini Clarinet Introduction, Theme and Variations von Weber Clarinet Concertino, op. 26 von Weber Clarinet Concerto No. 1 von Weber Clarinet Concerto No.2 Bennett Bass Clarinet Basswood Bozza Alto Sax Aria Debussy Alto Sax Rhapsodie Grundman Alto Sax Concertante Handel Alto Sax Adagio and Allegro Sonata #6 Husa Alto Sax Concerto Glazinov Alto Sax Concerto Whitney Alto Sax Introduction and Samba Devienne Tenor Sax Adagio and Allegro DeLuca Tenor Sax Beautiful Colorado Guilhaud Tenor Sax First Concertino Schmidt/Williams Tenor Sax Concerto for Tenor Sax Davis Baritone Sax Var.on a theme of Schumann Nelhybel Baritone Sax Concert Piece Aratunian Trumpet Concerto for Trumpet Arban Trumpet Fantasie Brillante Bellstedt Trumpet Napoli Bennett, Robt Russell Trumpet Rose Variations Clarke Trumpet Bride of the Waves Clarke Trumpet Carnival of Venice Clarke Trumpet From the Shores of the Mighty Pacific Clarke Trumpet Maid of the Mist Clarke Trumpet Stars of the Veltvety Sky Clarke Trumpet Sounds from the Hudson Goedicke Trumpet Concert Etude Haydn, F.J. -

An Ethnomusicology of Disability Alex Lubet, Ph.D. School of Music University of Minnesota

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by ScholarSpace at University of Hawai'i at Manoa Tunes of Impairment: An Ethnomusicology of Disability Alex Lubet, Ph.D. School of Music University of Minnesota Abstract: "Tunes of Impairment: An Ethnomusicology of Disability" contemplates the theory and methodology of disability studies in music, a sub-field currently in only its earliest phase of development. The article employs as its test case the field of Western art ("classical") music and examines the reasons for the near total exclusion from training and participation in music performance and composition by people with disabilities. Among the issues around which the case is built are left-handedness as a disability; gender construction in classical music and its interface with disability; canon formation, the classical notion of artistic perfection and its analogy to the flawless (unimpaired) body; and technological and organizational accommodations in music-making present and future. Key words: music; disability; classical Introduction: The Social Model of Disability Current scholarship in Disability Studies (DS) and disability rights activism both subscribe to the social modeli that defines disability as a construct correlated to biological impairment in a manner analogous to the relationship between gender and sex in feminist theory.ii Disability is thus a largely oppressive practice that cultures visit upon persons with, or regarded as having, functional impairments. While social constructs of femininity may not always be oppressive, the inherent negative implications of 'dis-ability' automatically imply oppression or at least dis-advantage. Like constructions of gender, categorizations of disability are fluid; variable between and within cultures. -

Adagio (1950–51) Metamorphose (1953) Symphony No. 1, Sinfonia Austéra (1953–55, Rev

WORKS BY PER NØRGÅRD Works for Orchestra Preludio (1950–51) Adagio (1950–51) Metamorphose (1953) Symphony No. 1, Sinfonia austéra (1953–55, rev. 1956) Bright Dances (1959) Fragment VI (1959–61) The Young Man Is Getting Married (1964–68) Le jeune homme à marier — Suite (1965) Composition for Orchestra (1966) Töne vom Hernst (1966) Iris (1966–67, rev. 1968) Luna, Four Phases for Orchestra (1967) Århus’ tapre skrædder (1968) Voyage into the Golden Screen (1968) The Man Who Thought Things (1969) Tango Chikane (chamber orchestra version) (1969) Symphony No. 2, in one movement (1970, rev. 1971) Symphony No. 3, in two movements (1972–75) Dream Play (1975, rev. 1980) Twilight (1976–77, rev. 1979) Towards Freedom? (1977) Symphony No. 4, Indian Rose Garden and Chinese Witch Sea (1981) Surf (1983) Burn (1984) Symphony No. 5 (1990, rev. 1991) Spaces of Time (1991) Night-Symphonies, Day Breaks (1991–92) Fugitive Summer (1992) Out of This World — Hommage à Lutosławski (1994) Four Observations — From an Infinite Rapport. Hommage à Bartók (1995) Tributes — Album for strings (1995) Voyage into the Broken Screen, Hommage à Sibelius (1995) Aspects of Leaving (1997) (more) Symphony No. 6, At the End of the Day (1997–99, rev. 2000) Terrains Vagues (2000) Intonation/Detonation (2001) Symphony No. 7 (2004–06) Lysning (Glade) (2006) Symphony No. 8 (2010–11) Works for Soloist(s) and Orchestra Rhapsody — in D (for piano) (1952) Concerto for Piano and Orchestra (1955–58) Nocturnes, Fragment VII (for soprano) (1961–62) Three Love Songs (for alto) (1963) Recall — Concerto for Accordion (1968) For a Change — Percussion Concerto No. -

February 22, 2012 SUPPLEMENT CHRISTOPHER ROUSE

FOR RELEASE: February 22, 2012 SUPPLEMENT CHRISTOPHER ROUSE THE 2012–13 MARIE-JOSÉE KRAVIS COMPOSER-IN-RESIDENCE First Season of Two-Year Term: WORLD PREMIERE, SEEING, PHANTASMATA Advisory Role on CONTACT!, with WORLD, U.S., AND NEW YORK PREMIERES, Led by JAYCE OGREN and ALAN GILBERT _____________________________________ “I just love the Philharmonic musicians: I love working with them, and they play my music with incredible commitment. As a kid in Baltimore I grew up with their recordings, and then, of course, I also heard them on the Young People’s Concerts on television. I’ve always had a special feeling for the Philharmonic because the musicians have always played like they really meant it, with such energy and commitment; and when I got older and wrote music that they played, they did it the same way. I’m thrilled to be able to work with them more closely.” — Christopher Rouse _______________________________________ Christopher Rouse has been named The Marie-Josée Kravis Composer-in-Residence at the Philharmonic, and will begin his two-year tenure in the 2012–13 season. He is the second composer to hold this title, following the tenure of Magnus Lindberg. The Pulitzer Prize- and Grammy Award-winning American composer will be represented by three works with the Philharmonic this season in concerts conducted by Alan Gilbert: Phantasmata, February 21 and 22, 2013; a World Premiere–New York Philharmonic Commission, April 17–20, 2013, which will also be taken on the EUROPE / SPRING 2013 tour; and the reprise of Seeing for Piano and Orchestra (commissioned by the Philharmonic and premiered in 1999), June 20–22, 2013, performed by Emanuel Ax, the 2012–13 Mary and James G. -

Program Notes by Jonathan Leshnoff and Dr

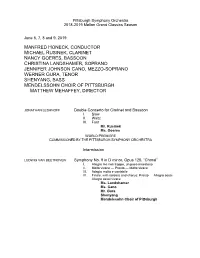

Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra 2018-2019 Mellon Grand Classics Season June 6, 7, 8 and 9, 2019 MANFRED HONECK, CONDUCTOR MICHAEL RUSINEK, CLARINET NANCY GOERES, BASSOON CHRISTINA LANDSHAMER, SOPRANO JENNIFER JOHNSON CANO, MEZZO-SOPRANO WERNER GURA, TENOR SHENYANG, BASS MENDELSSOHN CHOIR OF PITTSBURGH MATTHEW MEHAFFEY, DIRECTOR JONATHAN LESHNOFF Double Concerto for Clarinet and Bassoon I. Slow II. Waltz III. Fast Mr. Rusinek Ms. Goeres WORLD PREMIERE COMMISSIONED BY THE PITTSBURGH SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA Intermission LUDWIG VAN BEETHOVEN Symphony No. 9 in D minor, Opus 125, “Choral” I. Allegro ma non troppo, un poco maestoso II. Molto vivace — Presto — Molto vivace III. Adagio molto e cantabile IV. Finale, with soloists and chorus: Presto — Allegro assai — Allegro assai vivace Ms. Landshamer Ms. Cano Mr. Gura Shenyang Mendelssohn Choir of Pittsburgh June 6-9, 2019, page 1 PROGRAM NOTES BY JONATHAN LESHNOFF AND DR. RICHARD E. RODDA JONATHAN LESHNOFF Double Concerto for Clarinet and Bassoon (2018) Jonathan Leshnoff was born in New Brunswick, New Jersey on September 8, 1973, and resides in Baltimore, Maryland. His works have been performed by more than 65 orchestras worldwide in hundreds of orchestral concerts. He has received commissions from Carnegie Hall, the Philadelphia Orchestra, and the symphony orchestras of Atlanta, Baltimore, Dallas, Kansas City, Nashville, and Pittsburgh. His Double Concerto for Clarinet and Bassoon was commissioned by the Pittsburgh Symphony and co-commissioned by the Greenwich Village Orchestra and International Wolfegg Concerts of Wolfegg, Germany. These performances mark the world premiere. The score calls for piccolo, two flutes, two oboes, English horn, two clarinets, bass clarinet, two bassoons, contrabassoon, four horns, two trumpets, three trombones, tuba, timpani, percussion, harp, and strings. -

Ambassador Auditorium Collection ARS.0043

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt3q2nf194 No online items Guide to the Ambassador Auditorium Collection ARS.0043 Finding aid prepared by Frank Ferko and Anna Hunt Graves This collection has been processed under the auspices of the Council on Library and Information Resources with generous financial support from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation. Archive of Recorded Sound Braun Music Center 541 Lasuen Mall Stanford University Stanford, California, 94305-3076 650-723-9312 [email protected] 2011 Guide to the Ambassador Auditorium ARS.0043 1 Collection ARS.0043 Title: Ambassador Auditorium Collection Identifier/Call Number: ARS.0043 Repository: Archive of Recorded Sound, Stanford University Libraries Stanford, California 94305-3076 Physical Description: 636containers of various sizes with multiple types of print materials, photographic materials, audio and video materials, realia, posters and original art work (682.05 linear feet). Date (inclusive): 1974-1995 Abstract: The Ambassador Auditorium Collection contains the files of the various organizational departments of the Ambassador Auditorium as well as audio and video recordings. The materials cover the entire time period of April 1974 through May 1995 when the Ambassador Auditorium was fully operational as an internationally recognized concert venue. The materials in this collection cover all aspects of concert production and presentation, including documentation of the concert artists and repertoire as well as many business documents, advertising, promotion and marketing files, correspondence, inter-office memos and negotiations with booking agents. The materials are widely varied and include concert program booklets, audio and video recordings, concert season planning materials, artist publicity materials, individual event files, posters, photographs, scrapbooks and original artwork used for publicity. -

Focus Day 2011: Five Decades of New Music for Percussion: 1961

Focus Day 2011 Five Decades of New Music for Percussion: 1961–2011 In celebration of the 50th Anniversary of the Percussive Arts Society, the New Music/Research Focus Day 2011 Committee is extremely excited to present Focus Day 2011: Five Decades of New Music for Percussion. Featuring masterworks of the last fifty years of our repertoire performed by some of the most significant artists of our generation, Focus Day 2011 marks a monumental achievement for the Percussive Arts Society and its membership. As the Percussive Arts Society as a whole cel- ebrates its 50th anniversary, it is fitting that the New Music Research Committee is celebrating the “Five Decades of New Music for th 25 Anniversary of Focus Day (formerly New Music/Research Day) at PASIC. Since its founding by Stuart Smith in 1986, the mission of the New Music/Research Committee has been to present creative, innovative, and imaginative programming that exposes new compositional trends while Percussion 1961–2011” maintaining connections to the historically significant composers and performers of our field who together shaped the contemporary art-form of new music for percussion. Certainly, Focus Day 2011 defines this mission in every way. Many of the major masterworks by the most important composers of our field from 1961–2011 will be presented throughout the day, including works from Mark Applebaum, Herbert Brün, Michael Colgrass, Christopher Deane, Morton Feldman, Brian Ferneyhough, Michael Gordon, David Lang, Steve Reich, Paul Smad- beck, Stuart Smith, Karlheinz Stockhausen, Gordon Stout, Michael Udow, Julia Wolfe, and Ian- nis Xenakis. The New Music Research Committee also encourages the presentation of new and previously unknown works at PASIC, and we are delighted that Focus Day 2011 will include two PASIC Premieres—a unique new composition by Judith Shatin, and a truly epic new percussion ensemble work by one of the leading composers of our time, James Wood. -

Applied Percussion Syllabus & Handbook

ANGELO STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF ARTS & HUMANITIES DEPARTMENT OF VISUAL & PERFORMING ARTS APPLIED PERCUSSION SYLLABUS & HANDBOOK Instructor: Trent Shuey, D.M.A. | Office: Carr EFA 210 | Percussion Room: Carr EFA 288 | Email: [email protected] Office Phone: (325) 486-6036 | Cell Phone: (541) 314-2121 | Website: www.trentshuey.com Office Hours: Wednesday & Friday 10:00am-12:00pm | Percussion Studio Class: Monday 4-4:30PM (Room 288) Course Description Percussion studies at Angelo State University are designed to develop the highest possible level of musicianship, performance and teaching proficiency within a total percussion curriculum. Students will specifically focus on snare drum, two-mallet keyboards, four-mallet keyboards w/Stevens grip, timpani, multiple percussion and drumset. The understanding and development of technical facilities, a cross- section of literature, sight-reading skills and ensemble applications are required skills on each instrument, in addition to regular performances in studio classes, clinics/masterclasses and juries. Course Objectives Overall, to meet degree requirements students are expected to demonstrate significant proficiency in all areas of percussion including: 1) Snare Drum: Play all 40 Percussive Arts Society Standard Rudiments; Play a concert and rudimental snare drum roll; Play a concert snare drum etude using appropriate stickings, stroke types, embellishments, dynamics, playing areas and musicianship; Identify and perform important snare drum orchestral excerpts. 2) Keyboard: Play all major/minor (natural, harmonic & melodic) scales and arpeggios for three octaves; Play two-mallet and four-mallet etudes using appropriate stickings, stroke-types, dynamics, mallet choices and musicianship; Perform a four- mallet solo using appropriate stickings, stroke-types, dynamics, mallet choices and musicianship; Identify and perform important keyboard (xylophone and orchestra bells) orchestral excerpts. -

An Examination of David Maslanka's Marimba Concerti: Arcadia II For

AN EXAMINATION OF DAVID MASLANKA’S MARIMBA CONCERTI: ARCADIA II FOR MARIMBA AND PERCUSSION ENSEMBLE AND CONCERTO FOR MARIMBA AND BAND, A LECTURE RECITAL, TOGETHER WITH THREE RECITALS OF SELECTED WORKS OF K. ABE, M. BURRITT, J. SERRY, AND OTHERS Michael L. Varner, B.M.E., M.M. Dissertation Prepared for the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS December 1999 APPROVED: Thomas Clark, Major Professor Ron Fink, Major Professor John Michael Cooper, Minor Professor William V. May, Interim Dean of the College of Music C. Neal Tate, Dean of the Robert B. Toulouse School of Graduate Studies Varner, Michael L., An Examination of David Maslanka’s Marimba Concerti: Arcadia II for Marimba and Percussion Ensemble and Concerto for Marimba and Band, A Lecture Recital, Together with Three Recitals of Selected Works of K. Abe, M. Burritt, J. Serry, and Others. Doctor of Musical Arts (Performance), December 1999, 134 pp., 62 illustrations, bibliography, 40 titles. Although David Maslanka is not a percussionist, his writing for marimba shows a solid appreciation of the idiomatic possibilities developed by recent innovations for the instrument. The marimba is included in at least eighteen of his major compositions, and in most of those it is featured prominently. Both Arcadia II: Concerto for Marimba and Percussion Ensemble and Concerto for Marimba and Band display the techniques and influences that have become characteristic of his compositional style. However, they express radically different approaches to composition due primarily to Maslanka’s growth as a composer. Maslanka’s traditional musical training, the clear influence of diverse composers, and his sensitivity to extra-musical influences such as geographic location have resulted in a very distinct musical style.