Saltmarsh and Wetland

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wild Mersey Mountain Bike Development

Wild Mersey Mountain Bike Development Natural Values Report Warrawee Conservation Area through to Railton Prepared for : Kentish Council and Latrobe Council Report prepared by: Matt Rose Natural State PO Box 139, Ulverstone, TAS, 7315 www.naturalstate.com.au 1 | NATURAL STATE – PO Box 139, Ulverstone TAS 7315. Mobile: 0437 971 144 www.naturalstate.com.au Table of contents Executive Summary ......................................................................................................................................... 5 1 Introduction ................................................................................................................................................ 6 1.1 Background ........................................................................................................................................... 6 1.2 Description of the proposed development activities ...................................................................... 6 1.3 Description of the study areas ............................................................................................................ 8 1.4 The Warrawee Conservation Area ..................................................................................................... 8 1.5 Warrawee to Railton trail ..................................................................................................................... 8 2 Methodology .............................................................................................................................................. -

Ramsar Sites in Order of Addition to the Ramsar List of Wetlands of International Importance

Ramsar sites in order of addition to the Ramsar List of Wetlands of International Importance RS# Country Site Name Desig’n Date 1 Australia Cobourg Peninsula 8-May-74 2 Finland Aspskär 28-May-74 3 Finland Söderskär and Långören 28-May-74 4 Finland Björkör and Lågskär 28-May-74 5 Finland Signilskär 28-May-74 6 Finland Valassaaret and Björkögrunden 28-May-74 7 Finland Krunnit 28-May-74 8 Finland Ruskis 28-May-74 9 Finland Viikki 28-May-74 10 Finland Suomujärvi - Patvinsuo 28-May-74 11 Finland Martimoaapa - Lumiaapa 28-May-74 12 Finland Koitilaiskaira 28-May-74 13 Norway Åkersvika 9-Jul-74 14 Sweden Falsterbo - Foteviken 5-Dec-74 15 Sweden Klingavälsån - Krankesjön 5-Dec-74 16 Sweden Helgeån 5-Dec-74 17 Sweden Ottenby 5-Dec-74 18 Sweden Öland, eastern coastal areas 5-Dec-74 19 Sweden Getterön 5-Dec-74 20 Sweden Store Mosse and Kävsjön 5-Dec-74 21 Sweden Gotland, east coast 5-Dec-74 22 Sweden Hornborgasjön 5-Dec-74 23 Sweden Tåkern 5-Dec-74 24 Sweden Kvismaren 5-Dec-74 25 Sweden Hjälstaviken 5-Dec-74 26 Sweden Ånnsjön 5-Dec-74 27 Sweden Gammelstadsviken 5-Dec-74 28 Sweden Persöfjärden 5-Dec-74 29 Sweden Tärnasjön 5-Dec-74 30 Sweden Tjålmejaure - Laisdalen 5-Dec-74 31 Sweden Laidaure 5-Dec-74 32 Sweden Sjaunja 5-Dec-74 33 Sweden Tavvavuoma 5-Dec-74 34 South Africa De Hoop Vlei 12-Mar-75 35 South Africa Barberspan 12-Mar-75 36 Iran, I. R. -

Partial Flora Survey Rottnest Island Golf Course

PARTIAL FLORA SURVEY ROTTNEST ISLAND GOLF COURSE Prepared by Marion Timms Commencing 1 st Fairway travelling to 2 nd – 11 th left hand side Family Botanical Name Common Name Mimosaceae Acacia rostellifera Summer scented wattle Dasypogonaceae Acanthocarpus preissii Prickle lily Apocynaceae Alyxia Buxifolia Dysentry bush Casuarinacea Casuarina obesa Swamp sheoak Cupressaceae Callitris preissii Rottnest Is. Pine Chenopodiaceae Halosarcia indica supsp. Bidens Chenopodiaceae Sarcocornia blackiana Samphire Chenopodiaceae Threlkeldia diffusa Coast bonefruit Chenopodiaceae Sarcocornia quinqueflora Beaded samphire Chenopodiaceae Suada australis Seablite Chenopodiaceae Atriplex isatidea Coast saltbush Poaceae Sporabolis virginicus Marine couch Myrtaceae Melaleuca lanceolata Rottnest Is. Teatree Pittosporaceae Pittosporum phylliraeoides Weeping pittosporum Poaceae Stipa flavescens Tussock grass 2nd – 11 th Fairway Family Botanical Name Common Name Chenopodiaceae Sarcocornia quinqueflora Beaded samphire Chenopodiaceae Atriplex isatidea Coast saltbush Cyperaceae Gahnia trifida Coast sword sedge Pittosporaceae Pittosporum phyliraeoides Weeping pittosporum Myrtaceae Melaleuca lanceolata Rottnest Is. Teatree Chenopodiaceae Sarcocornia blackiana Samphire Central drainage wetland commencing at Vietnam sign Family Botanical Name Common Name Chenopodiaceae Halosarcia halecnomoides Chenopodiaceae Sarcocornia quinqueflora Beaded samphire Chenopodiaceae Sarcocornia blackiana Samphire Poaceae Sporobolis virginicus Cyperaceae Gahnia Trifida Coast sword sedge -

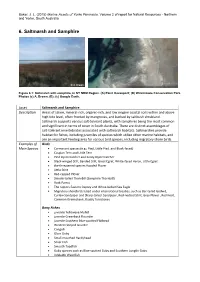

Saltmarsh and Samphire

Baker, J. L. (2015) Marine Assets of Yorke Peninsula. Volume 2 of report for Natural Resources - Northern and Yorke, South Australia 6. Saltmarsh and Samphire © A. Brown Figure 6.1: Saltmarsh with samphire, in NY NRM Region. (A) Point Davenport; (B) Winninowie Conservation Park. Photos (c) A. Brown. (B): (c) Google Earth. Asset Saltmarsh and Samphire Description Areas of saline, mineral-rich, organic-rich, and low oxygen coastal soils within and above high tide level, often fronted by mangroves, and backed by saltbush shrubland. Saltmarsh supports various salt-tolerant plants, with samphires being the most common and significant in terms of cover in South Australia. There are distinct assemblages of salt-tolerant invertebrates associated with saltmarsh habitats. Saltmarshes provide habitat for fishes, including juveniles of species which utilise other marine habitats, and are an important feeding area for various bird species, including migratory shore birds. Examples of Birds Main Species Cormorant species (e.g.; Pied, Little Pied, and Black-faced) Caspian Tern and Little Tern Pied Oystercatcher and Sooty Oystercatcher Black-winged Stilt, Banded Stilt, Great Egret, White-faced Heron, Little Egret the threatened species Hooded Plover Little Stint Red-capped Plover Slender-billed Thornbill (Samphire Thornbill) Rock Parrot The raptors Eastern Osprey and White-bellied Sea Eagle Migratory shorebirds listed under international treaties, such as Bar-tailed Godwit, Curlew Sandpiper and Sharp-tailed Sandpiper, Red-necked Stint, Grey Plover , Red Knot, Common Greenshank, Ruddy Turnstones Bony Fishes juvenile Yelloweye Mullet juvenile Greenback Flounder juvenile Southern Blue-spotted Flathead Western Striped Grunter Congolli Glass Goby Small-mouthed Hardyhead Silver Fish Smooth Toadfish Goby species such as Blue-spotted Goby and Southern Longfin Goby Adelaide Weedfish Baker, J. -

Jervis Bay Territory Page 1 of 50 21-Jan-11 Species List for NRM Region (Blank), Jervis Bay Territory

Biodiversity Summary for NRM Regions Species List What is the summary for and where does it come from? This list has been produced by the Department of Sustainability, Environment, Water, Population and Communities (SEWPC) for the Natural Resource Management Spatial Information System. The list was produced using the AustralianAustralian Natural Natural Heritage Heritage Assessment Assessment Tool Tool (ANHAT), which analyses data from a range of plant and animal surveys and collections from across Australia to automatically generate a report for each NRM region. Data sources (Appendix 2) include national and state herbaria, museums, state governments, CSIRO, Birds Australia and a range of surveys conducted by or for DEWHA. For each family of plant and animal covered by ANHAT (Appendix 1), this document gives the number of species in the country and how many of them are found in the region. It also identifies species listed as Vulnerable, Critically Endangered, Endangered or Conservation Dependent under the EPBC Act. A biodiversity summary for this region is also available. For more information please see: www.environment.gov.au/heritage/anhat/index.html Limitations • ANHAT currently contains information on the distribution of over 30,000 Australian taxa. This includes all mammals, birds, reptiles, frogs and fish, 137 families of vascular plants (over 15,000 species) and a range of invertebrate groups. Groups notnot yet yet covered covered in inANHAT ANHAT are notnot included included in in the the list. list. • The data used come from authoritative sources, but they are not perfect. All species names have been confirmed as valid species names, but it is not possible to confirm all species locations. -

Introduction Methods Results

Papers and Proceedings Royal Society ofTasmania, Volume 1999 103 THE CHARACTERISTICS AND MANAGEMENT PROBLEMS OF THE VEGETATION AND FLORA OF THE HUNTINGFIELD AREA, SOUTHERN TASMANIA by J.B. Kirkpatrick (with two tables, four text-figures and one appendix) KIRKPATRICK, J.B., 1999 (31:x): The characteristics and management problems of the vegetation and flora of the Huntingfield area, southern Tasmania. Pap. Proc. R. Soc. Tasm. 133(1): 103-113. ISSN 0080-4703. School of Geography and Environmental Studies, University ofTasmania, GPO Box 252-78, Hobart, Tasmania, Australia 7001. The Huntingfield area has a varied vegetation, including substantial areas ofEucalyptus amygdalina heathy woodland, heath, buttongrass moorland and E. amygdalina shrubbyforest, with smaller areas ofwetland, grassland and E. ovata shrubbyforest. Six floristic communities are described for the area. Two hundred and one native vascular plant taxa, 26 moss species and ten liverworts are known from the area, which is particularly rich in orchids, two ofwhich are rare in Tasmania. Four other plant species are known to be rare and/or unreserved inTasmania. Sixty-four exotic plantspecies have been observed in the area, most ofwhich do not threaten the native biodiversity. However, a group offire-adapted shrubs are potentially serious invaders. Management problems in the area include the maintenance ofopen areas, weed invasion, pathogen invasion, introduced animals, fire, mechanised recreation, drainage from houses and roads, rubbish dumping and the gathering offirewood, sand and plants. Key Words: flora, forest, heath, Huntingfield, management, Tasmania, vegetation, wetland, woodland. INTRODUCTION species with the most cover in the shrub stratum (dominant species) was noted. If another species had more than half The Huntingfield Estate, approximately 400 ha of forest, the cover ofthe dominant one it was noted as a codominant. -

Information Sheet on Ramsar Wetlands (RIS) – 2009-2012 Version

Information Sheet on Ramsar Wetlands (RIS) – 2009-2012 version Available for download from http://www.ramsar.org/ris/key_ris_index.htm. Categories approved by Recommendation 4.7 (1990), as amended by Resolution VIII.13 of the 8th Conference of the Contracting Parties (2002) and Resolutions IX.1 Annex B, IX.6, IX.21 and IX. 22 of the 9th Conference of the Contracting Parties (2005). Notes for compilers: 1. The RIS should be completed in accordance with the attached Explanatory Notes and Guidelines for completing the Information Sheet on Ramsar Wetlands. Compilers are strongly advised to read this guidance before filling in the RIS. 2. Further information and guidance in support of Ramsar site designations are provided in the Strategic Framework and guidelines for the future development of the List of Wetlands of International Importance (Ramsar Wise Use Handbook 14, 3rd edition). A 4th edition of the Handbook is in preparation and will be available in 2009. 3. Once completed, the RIS (and accompanying map(s)) should be submitted to the Ramsar Secretariat. Compilers should provide an electronic (MS Word) copy of the RIS and, where possible, digital copies of all maps. 1. Name and address of the compiler of this form: FOR OFFICE USE ONLY. DD MM Y Y Department of Primary Industries, Parks, Water and Environment (DPIPWE) GPO Box 44 HOBART Tasmania 7001 Designation date Site Reference Number Australia Ph: +61 3 6233 8011 2. Date this sheet was completed/updated: July 2012 3. Country: Australia 4. Name of the Ramsar site: The precise name of the designated site in one of the three official languages (English, French or Spanish) of the Convention. -

Ecological Influences in the Biogeography of the Austral Sedges

ECOLOGICALINFLUENCESINTHEBIOGEOGRAPHYOFTHE AUSTRALSEDGES jan-adriaan viljoen Dissertation presented in fulfillment of the requirements for the degree MSc in Botany Department of Biological Sciences Faculty of Sciences University of Cape Town UniversityFebruary of2016 Cape Town The copyright of this thesis vests in the author. No quotation from it or information derived from it is to be published without full acknowledgement of the source. The thesis is to be used for private study or non- commercial research purposes only. Published by the University of Cape Town (UCT) in terms of the non-exclusive license granted to UCT by the author. University of Cape Town Jan-Adriaan Viljoen. Ecological influences in the biogeography of the aus- tral sedges. MSc dissertation. University of Cape Town. Cape Town. February 2016. supervisors: A. Muthama Muasya G. Anthony Verboom ABSTRACT The biogeographic history of a species is a result of both stochastic processes such as dispersal and habitat filters that determine where a population with a given set of biological requirements can become es- tablished. In this dissertation, I examine the geographical and ecolog- ical distribution of the sedge tribe Schoeneae in conjunction with its inferred speciation history in order to determine the pattern of disper- sal and the environmental factors that have influenced establishment. The biogeographic reconstruction indicates numerous transoceanic dispersal events consistent with random diffusion from an Australian point of origin, but with a bias towards habitats with vegetation type and moisture regime similar to the ancestral conditions of the given subgroup (open and dry habitats in the majority of cases). The global distribution of the tribe also suggests a preference for low-nutrient soils, which I investigate at the local (microhabitat) scale by contrast- ing the distributions of the tribes Schoeneae and Cypereae on the Cape Peninsula along soil fertility axes. -

Origin and Age of Australian Chenopodiaceae

ARTICLE IN PRESS Organisms, Diversity & Evolution 5 (2005) 59–80 www.elsevier.de/ode Origin and age of Australian Chenopodiaceae Gudrun Kadereita,Ã, DietrichGotzek b, Surrey Jacobsc, Helmut Freitagd aInstitut fu¨r Spezielle Botanik und Botanischer Garten, Johannes Gutenberg-Universita¨t Mainz, D-55099 Mainz, Germany bDepartment of Genetics, University of Georgia, Athens, GA 30602, USA cRoyal Botanic Gardens, Sydney, Australia dArbeitsgruppe Systematik und Morphologie der Pflanzen, Universita¨t Kassel, D-34109 Kassel, Germany Received 20 May 2004; accepted 31 July 2004 Abstract We studied the age, origins, and possible routes of colonization of the Australian Chenopodiaceae. Using a previously published rbcL phylogeny of the Amaranthaceae–Chenopodiaceae alliance (Kadereit et al. 2003) and new ITS phylogenies of the Camphorosmeae and Salicornieae, we conclude that Australia has been reached in at least nine independent colonization events: four in the Chenopodioideae, two in the Salicornieae, and one each in the Camphorosmeae, Suaedeae, and Salsoleae. Where feasible, we used molecular clock estimates to date the ages of the respective lineages. The two oldest lineages both belong to the Chenopodioideae (Scleroblitum and Chenopodium sect. Orthosporum/Dysphania) and date to 42.2–26.0 and 16.1–9.9 Mya, respectively. Most lineages (Australian Camphorosmeae, the Halosarcia lineage in the Salicornieae, Sarcocornia, Chenopodium subg. Chenopodium/Rhagodia, and Atriplex) arrived in Australia during the late Miocene to Pliocene when aridification and increasing salinity changed the landscape of many parts of the continent. The Australian Camphorosmeae and Salicornieae diversified rapidly after their arrival. The molecular-clock results clearly reject the hypothesis of an autochthonous stock of Chenopodiaceae dating back to Gondwanan times. -

Lutregala Marsh Reserve: Background Report

Lutregala Marsh Reserve: Background Report www.tasland.org.au Lutregala Marsh Reserve: Background Report Tasmanian Land Conservancy (2016). Lutregala Marsh Reserve Background Report. Tasmanian Land Conservancy, Tasmania Australia 7005. Copyright ©Tasmanian Land Conservancy The views expressed in this report are those of the Tasmanian Land Conservancy and not the Federal or State Governments. This work is copyright but may be reproduced for study, research or training purposes subject to an acknowledgment of the sources and no commercial usage or sale. Requests and enquires concerning reproduction and rights should be addressed to the Tasmanian Land Conservancy. Front Image: Bruny Island Environmental Network volunteers helping erect property signs © Sally Bryant Contact Address Tasmanian Land Conservancy PO Box 2112, Lower Sandy Bay, 827 Sandy Bay Road, Sandy Bay TAS 7005 | p: 03 6225 1399 | www.tasland.org.au Lutregala Marsh Reserve Background Document Page 2 of 23 Table of Contents Acronyms ................................................................................................................................................................. 4 Acknowledgements ................................................................................................................................................. 5 Background ........................................................................................................................................................... 6 Introduction ......................................................................................................................................................... -

NORTH SCOTTSDALE BOTANICAL & FAUNA HABITAT SURVEY For

BOTANICAL & FAUNA HABITAT SURVEY FOR ABX4 PTY LTD: NORTH SCOTTSDALE NORTH SCOTTSDALE BOTANICAL & FAUNA HABITAT SURVEY For ABX4 PTY LTD 15th February 2013 PHILIP MILNER LANDSCAPE CONSULTANT PTY LTD 144 Allisons Road, LOWER BARRINGTON POSTAL: C/O Post Office, BARRINGTON, 7306 TASMANIA Mobile: 0417 052 605 Home Phone: (03) 6492 3201 Email: [email protected] A.B.N.No. 32 068 906 258 1/31 PHILIP MILNER LANDSCAPE CONSULTANT PTY LTD ……………………………….. 15th February 2013 BOTANICAL & FAUNA HABITAT SURVEY FOR ABX4 PTY LTD: NORTH SCOTTSDALE CONTENTS 1.0 Introduction 1.1 Objectives 1.2 Location of Study Area 1.3 Site Description 2.0 Desktop Survey of Natural Values 2.1 Desktop Survey Results 3.0 Field Survey 3.1 Field Survey Results 4.0 Recommendations APPENDIX 1: Vegetation Communities and Species Recorded References PHOTOS 2/31 PHILIP MILNER LANDSCAPE CONSULTANT PTY LTD ……………………………….. 15th February 2013 BOTANICAL & FAUNA HABITAT SURVEY FOR ABX4 PTY LTD: NORTH SCOTTSDALE 1.0 Introduction: ABX4 Pty Ltd a wholly owned subsidiary of Australian Bauxite Ltd is undertaking an exploratory program in an area to the north of Scottsdale and is proposing to undertake a drilling program of targeted locations within State Forest, Forest Reserve and freehold properties within the EL. The exploration program will involve numerous shallow drill holes which will not require the clearing and/or leveling of drill pad sites and so is expected to have a minimal impact on the ground surface and adjacent vegetation. A botanical and fauna habitat survey is required of the target areas as part of the MRT licence conditions to determine any likely impacts on threatened species, threatened vegetation communities and other natural values. -

080057-03.001.Pdf

'urirJo uels pu€ r"IToJ olur uorsr^rp e lset8ns pFoc l"ql ql?oqs eql ur uorl"cr"rusp ,{l?punoq Jo I€rJol?ru 'ut{€.{) Jo ou sI eJeql l?ql luer?dd€ sr lI tcoJJoc sI aoIA Jo^aqclql6 (€96I segol "uts ol peanpor oJBse^"el eql l?ql pu€ xolroc enJl ? slueseJdeJql€eqs lualn$ns eql lEql paunss€ 'ue{leJ) sI 1r qclq,^Aut pasodord ueeq s"q eJnlcnJls e^rl"uJell€ uV (Lg6I ses"q Jeel ;o suorlrod I?u"q? luoJlnaop eql -,{qpepuno:rns srx€ ruels e;o dn epeu eq ol petunss€ ueaq .{11zreue3el"rl e€eproruJocrT?Soq} Jo crlsrlolr?J?qc s3qJusrq ol€lnJllJ" eyL :wals ,{SoloqdroN '(Z/6I uoslrlA) poqsllqnd ueeq ^p?orl€ se\I ou)oru)al snue8 eql uorsr,\er 'posr^eJ Jo v eJB"rJe.rlsny ur lusseJd Sureqs? pesruSoceJDJeueB xrs eql Jo e^g .radsdslql ul 'Bxel luenlrlsuoc JJor{l ^ueut osrsSocoJpu? €roue8 eql eleeullep ,{lJ"elc oloru ol 'sJerllo Jo 'se^rl"lussoJdeJ elqlssod uooq s"q lr Jo suerurcedspeup pooB pu€ atuosJo lEl.roleu pol{cld ro qse.ggo ,{11rge1e,r"eql qll,^A 'sercedspue ereue8 oq1 q}oq os"q o} q3lq,r uo 'uleql sJelr?J?gc oql o-lenp-,(pred pu" ol olq"lr"As ppq o^?q s}s[uouox€l eql luql Jo,{lrcned 'el?qop I"LrelEruJooo oql ol enp ,\ll.rBou00q sBq srqJ alqBloprsuoJJo esn€oeql uesq s"q ereue8 eql go uo4drrcsrunc:rc eq1 'e8€lqurass"elercsrp ? s? pesruSoceJ-,{lI?JeueB ueeq e^eq e€eploluloarl"S eql ellq,4A.