ROWDY GAINES: a WALK DOWN MEMORY LANE by Mark Muckenfuss

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Swimming for the Queen Save Record by Andrew P

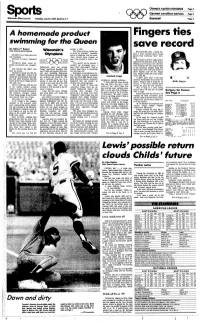

Olympic cyclist reinstated Page 2 Spoils Ganassi condition serious Page 2 Wisconsin State Journal Tuesday, July 24,1984, Section 2 • Baseball Page 3 A homemade product Fingers ties swimming for the Queen save record By Andrew P. Baggot Wisconsin's tember of 1979. State Journal sports reporter "My father always wanted me MILWAUKEE (AP) - Rollie Fin- to swim for England," Annabelle gers is more worried about saving •She didn't say a thing about tea Olympians said in a telephone visit last week. games than collecting "save" num- and crumpets. "He's always been English at bers. Princess Di wasn't mentioned heart and wanted to keep it that Milwaukee's veteran right-hander at all. way. registered his 23rd save of the season Liverpool's latest soccer tri- "If it weren't for my parents, I Monday in a 6-4 victory over the New umph was passed over complete- wouldn't be swimming here, I York Yankees. The save was his 216th ly. Parliament were not among know that," said added. "They've in the American League, tying him And, horrors, she didn't even Cripps' uppermost thoughts. She always been there to encourage with former New York and Texas re- have an accent. was 11 then, just another all-Amer- me and help me." liever Sparky Lyle for the league Chances are good, too, that An- ican girl, attending Edgewood Expensive encouragement, too. lead. Fingers holds the major-league nabelle Cripps didn't curtsy at all School in Madison and doing things The monthly overseas telephone Annabelle Cripps mark with 324. -

Tracy Caulkins: She's No

USS NATIONALS BY BILL BELL PHOTOGRAPHY BY DAN HELMS TRACY CAULKINS: SHE'S NO. 1 Way back in the good oi' Indeed, there was a very good 39 national championships, set 31 days, before Tracy Caulkins swimmer. He was an American. An individual American records and Olympic champion. A world record one world record (the 200 IM at the was a tiny gleam in her holder. His name was Johnny Woodlands in August 1978). parents' eyes, before Weissmuller. At the C)'Connell Center Pool anybody had heard of Mark Tarzan. He could swing from the here in Gainesville, April 7-10, Spitz or Donna de Varona or vines with the best of 'em. But during the U.S. Short Course Debbie Meyer, back even before entering show biz he was a Nationals, she tied Weissmuller's 36 wins by splashing to the 200 back before the East German great swimmer. The greatest American swimmer (perhaps the title opening night (1:57.77, just off Wundermadchen or Ann greatest in all the world) of his era. her American record 1:57.02). The Curtis or smog in Los He won 36 national championships next evening Tarzan became just Angeles or Pac-Man over a seven-year span (1921-28) another name in the U.S. Swimming .... there was a swimmer. and rather than king of the jungle, record book as Caulkins won the Weissmuller should have been more 400 individual medley for No. 37, accurately known as king of the swept to No. 38 Friday night (200 swimming pool. IM) and climaxed her 14th Na- From 100 yards or meters through tionals by winning the 100 breast 500 yards or 400 meters he was Saturday evening. -

Rowdy Gaines(Pdf)

Profile: Member of the 1980 Olympic Swim Team that boycotted the Olympics held in Moscow, then came back to win three gold medals in the 1984 Olympic Games in the 100m free, the 400m free relay and the 400m medley relay. Rowdy Gaines life is one of inspiration and courage. Gaines, born in Winter Haven, Florida, didn't start swimming until the age of 17. He tried other sports as youngster but was either to short, to slow, or not coordinated enough. As he recalls, "I wanted to play football but was so intimidated by the size of the other players." A shy boy growing up, Gaines found the solitude of swimming laps to be just what the doctor ordered. But his shyness quickly dissipated with his new found swimming success. After two years of rapid improvement as a high school swimmer, he was offered a scholarship to swim for Auburn University and under legendary coach Richard Quick. If it hadn't been for the 1980 Olympic boycott, Gaines might very well be one of America's most famous Olympians. He was favored to win 4 Olympic Gold Medals in 1980. He had broken 11 World Records. But as he says today, while disappointed by the decision to boycott, he supported President Carter and the U.S.A 100%. With every set back in his life, Gaines has persevered. He graduated from Auburn in 1981 and thought his swimming career was over. Professional swimming didn't exist at that time. He left the water for nearly a year, worked in his dad's gas station, and went through post-collegiate depression thinking he'd missed his dream to swim in the Olympics. -

NCAA Championships 11Th (128 Pts.) March 27-29 NCAA Championships Federal Way, Wash

649064-2 Swimming Guide.qxp:2008 Swimming Guide.qxd 12/7/07 9:19 AM Page 1 2007-08 Tennessee Swimming and Diving TABLE OF CONTENTS Media Information 1 Quick Facts and Phone Numbers 1 2007-08 Schedule and Top Returning Times 12 Team Roster 13 Season Outlook 14 2007-08 Opponents 15 Head Coach John Trembley 16-17 Bud Ford Coaching Staff 18-19 David Garner Associate Athletics Director Swimming Contact Head Diving Coach Dave Parrington 18-19 Media Relations Assistant Coach Joe Hendee 19 The 2007-08 Tennessee Men’s Swimming and Diving Media Guide is published pri- University Administration 20 marily as a source of information for reporters representing newspapers, television and Support Staff 21 radio stations, wire services and magazines. Persons with any questions regarding Tennessee men’s swimming and diving should not hesitate to call the UT Sports The Volunteers 22-33 Information Office. 2006-07 Season Review 34-37 PRESS SERVICES: Members of the media are provided official results at the conclusion 2007 SEC/NCAA Meet Results 36 of each home meet. Coaches and athletes are made available upon request as quickly as pos- 2007 Volunteer Honorees 37 sible after the meet. Telephones and a fax machine are available at the Tennessee Sports Through the Years 38 Information Office, 1720 Volunteer Blvd., in Room 261 of Stokely Athletics Center. Swimming and diving notes, information on upcoming meets and previous meet results are Dual-Meet History 39 available via the University of Tennessee’s athletics Web site at www.utsports.com. Year-by-Year Results 40-42 1978 NCAA Champions 43 FACILITIES: The Allan Jones Intercollegiate Aquatic Center and UT’s Student Aquatic Center both are located on Andy Holt Avenue. -

The NCAA News

ational Collegiate Athletic Association Official Notice to be mailed The Official Notice of the 1984 included in copies to athletic dents) and vacancies on the NCAA NCAA Convention will be mailed directors, reminding them that Council, as proposed by the November 22 to the chiefexecutive the chief executive officers of Nominating Committee. officer, faculty athletic represen- their institutions receive the This is the second year that the tative, director of athletics and delegate appointment forms. Nominating Committee’s recom- primary woman administrator of Also included in the Official mendations have been distributed athletics programs at each active Notice is an up-to-date schedule to the membership prior to the member institution, as well as to of meetings being held January Convention. The committee’s officers of allied and affiliated 6-12 in conjunction with the 78th recommendations also will be members. annual NCAA Convention. featured in the November 2 I issue Included in the annual publi- of The NCAA News. cation are all 162 proposed All members are urged to review Accompanying the Nominating amendments to the Association’s the opening section of the Official Committee’s recommendations in legislation that were submitted Notice, which sets forth in detail the Official Notice is a review of by the November 1 deadline. the procedure for appointing dele- the Council-approved procedures Chief executive officers receive gates and other pertinent policies for nominating and electing with their copies the official forms regarding Convention operations members of the Council and on which CEOs appoint their and voting. NCAA officers. That information delegates to the Convention, which The official Notice also contains also will be reprinted in the will be held January 9-l I, 1983, an appendix listing the candidates Convention Program, which is at Loews Anatole Hotel, Dallas, being proposed for NCAA offcers distributed at the Convention Texas. -

2018-19 Almanac

2018-19 AUBURN SWIMMING & DIVING ALMANAC TABLE OF CONTENTS QUICK FACTS INFORMATION Location .............................................................. Auburn, Ala. Table of Contents/Quick Facts .............................................................................................................................1 Founded ................................................................Oct. 1, 1856 2018-19 Rosters ...........................................................................................................................................................2 Enrollment ......................................................................29,776 2018-19 Schedule ......................................................................................................................................................3 Nickname .........................................................................Tigers COACHING STAFF School Colors .................Burnt Orange and Navy Blue Head Coach Gary Taylor ....................................................................................................................................4-5 Facility ......James E. Martin Aquatics Center (1,000) Diving Coach Jeff Shaffer.................................................................................................................................. 6-7 Affiliation .....................................................NCAA Division I Assistant Coach Michael Joyce ...........................................................................................................................8 -

Swimming and Diving DIVISION I MEN’S

Swimming and Diving DIVISION I MEN’S Highlights Michigan wins fi rst championship since 1995, 12th overall: — When Michigan’s Bruno Ortiz pulled himself out of the water after swimming the anchor leg in the 400- yard freestyle relay at the 2013 Division I Men’s Swimming and Diving Championships, the singing started. “Hail to the Victors” echoed around the Indiana University Natatorium at IUPUI March 30, beginning with two Michigan spectator sections on one side of the building and carrying over to the Michigan bench area on the pool deck. The Wolverines did not win the 400 free relay; they fi nished second. But it didn’t matter. Michigan had wrapped up its fi rst national team title since 1995 long before that fi nal relay event. It was the 12th national title for Michigan, and meant it was no longer tied with Ohio State for the overall lead in Division I men’s titles. “This morning, we just kind of let our passion drive us. And that was it,” said Connor Jaeger, who began Michigan’s title drive on the fi nal night of the three-day meet with a victory in the 1,650-yard freestyle. He also won the 500 free in the meet’s fi rst individual race. Michigan’s victory halted a two-year title run by California, which fi nished second. “We started four years ago working on this,” said Michigan’s fi fth-year coach Mike Bottom. “You do it one day at a time; you do it one student-athlete at a time. -

National Collegiate Athletic Association

NATIONAL COLLEGIATE ATHLETIC ASSOCIATION OFFICIAL SUMMARY 49th NCAA SWIMMING & DIVING CHAMPIONSHIPS MARCH 23, 24, 25, 1972 OLYMPIC POOL UNITED STATES MILITARYACADEMY WEST POINT, NEW YORK MEET OFFICIALS DIREDCOTR OF OFFICIALS: MR. CHARLEST BUTT STARTERS: MR. JOE ROGERS – MR. KENNETH TREADYWAY CHIEF TIMER: MR. THOMAS STUBBS CHIEF JUDGE: MR. ED FEDOWSKY STROKE INSPECTORS TURN JUDGES ED. LEIBINGER LANE 1. CHARLIE ARNOLD DICK HELLER LANE 2. DAVE ALLEN DICK ANDERSON LANE 3. RICHARD SCHLIERKERS JIM SPREITZER LANE 4. TOM LIOTTI LANE 5. SAM FREAS LANE 6. BILL MILLER LANE 7. JOHN SPRING LANE 8. JOE STETZ TIMERS LANE 1. EDWARD E. GRAY LANE 5. STEVE MAHONEY BOB SLAUGHTER DAVID BARTHOLOW J. ROBERT MTHENEY ROBERT A. BRUCE LANE 2. ALEXANDER BUNCHER LANE 6. ROBERT A. WILSON A. M. TRUMBATORE LT. JOHN RYAN HOWARD BETHEL DUNCAN P. HINCKLEY LANE 3. TONY MALINOWSKI LANE 7. JAMES RANKIN CHARLES W. BROWN JOHN P. BOURASSA CHARLES J. HATTER EMANUEL S. RATNER LANE 4. VICTOR B. LISKE LANE 8. ROY EDWARD STALEY HAROLD PAULSON RICHARD L. TETCHELEKIS ALLEN GOODWIN JOHN ARCIENGA SCORING TABLE MR. ROBERT BARTELS MR. VIC GUSTAFSON MR. ROBERT MOWERSON MR. WILLIAM HEUSNER MR. GREG WRIGHT OFFICIALS FOR DIVING EVENTS DIVING COORDINATORS: MR. TED BITONDO – WIN YOUNG REFEREE: MR. DAVE GLANDERS ANNOUNCERS: JIM WOOD – JERRY DARDA SCORING TABLE ROLLIE BESTER JACK ROMAINE FLETCHER GILDERS JIM HARTMAN JERRY SYMONS MRS. JOHN WALKER JOHN WALKER BIM STULTS BRETT EVANS JUDGING PANEL HOBIE BILLINGSLEY DICK SMITH DOB WEBSTER JIM WOOD MIKE MAYFIELD DOUGLAS WILLIAMS DON MCGOVERN RICK GILBERT BIM STULTS DENNY GOLDEN WARD O’CONNELL MEET ADMINISTRATION MEET DIRECTOR COLONEL JACK SCHUDER DIRECTOR OF ATHLETICS - USMA MEET MANAGER ASSISTANT MEET MANAGERS JACK RYAN DAN MILNE - SWIMMING A/ATHLETIC DIRECTOR ASST. -

USC's Mcdonald's Swim Stadium

2003-2004 USC Swimming and Diving USC’s McDonald’s Swim Stadium Home of Champions The McDonald’s Swim Stadium, the site of the 1984 Olympic swimming and diving competition, the 1989 U.S. Long Course Nationals and the 1991 Olympic Festival swimming and diving competition, is comprised of a 50-meter open-air pool next to a 25-yard, eight-lane diving well featuring 5-, 7 1/2- and 10- meter platforms. The home facility for both the USC men’s and women’s swimming and diving teams conforms to all specifications and requirements of the International Swimming Federation (FINA). One of the unusual features of the pool is a set of movable bulkheads, one at each end of the pool. These bulkheads are riddled with tiny holes to allow the water to pass Kennedy Aquatics Center, which houses locker features is the ability to show team names and through and thus absorb some of the waves facilities and coaches’ offices for both men’s scores, statistics, game times and animation. that crash into the pool ends. The bulkheads and women’s swimming and diving. It has a viewing distance of more than 200 can be moved, so that the pool length can be The Peter Daland Wall of Champions, yards and a viewing angle of more than 160 adjusted anywhere up to 50 meters. honoring the legendary USC coach’s nine degrees. The McDonald’s Swim Complex is located NCAA Championship teams, is located on the The swim stadium celebrated its 10th in the northwest corner of the USC campus, exterior wall of the Lyon Center. -

American Swimming Magazine Published for the American Swimming Coaches Association by the American Swimming Coaches Council for Sport Development

VOL 2021 | ISSUE 2 AMERICAN Staying Engaged in the Sport of Swimming in the Age of Gaming and Social Media: Creating the Game of Swimming by Thomas Meek on page 8 TM AMERICA'S #1 SWIM CAMPS FEATURES American Swimming Magazine Published for the American Swimming Coaches Association by the American Swimming Coaches Council for Sport Development. Snorkel Train Your Breaststroke 4 Board of Directors: by Coach Cokie Lepinski, Sun City President: Mike Koleber Creating the Game of swimming 8 Vice President of Fiscal Oversight: by Thomas Meek Dave Gibson Treasurer: Chad Onken The “Impossible” 12 by Ulysses Perez Secretary: Michael Murray At-Large Member: Matt Kredich Members: David Marsh, David C. Salo, Ken Heis, Jeff Julian, Mark Schubert, Jim Tierney, Megan Oesting, Mitch Dalton, Braden Holloway, Doug Wharam ASCA CEO Jennifer LaMont ASCA Staff Digital Director: Kyle Mills Membership Services: Matt Hooper Publications: Salomon Soza SwimAmerica Account Manager: Karen Downey The Magazine for Professional Swimming Coaches. A Publication of the American Swimming Coaches Council for Sport Development, American Swimming Magazine (ISSN: 0747-6000) is published by the American Swimming Coaches Association. Membership/subscription price is $88.00 per year (US). International $132.00. Disseminating swimming knowledge to swimming coaches since 1958. Postmaster: Send address changes to: American Swimming Coaches Association, 6750 N. Andrews Ave. Fort Lauderdale, FL 33309 (954) 563-4930 | Toll Free: 1 (800) 356-2722 | Fax: (954) 563-9813 | swimmingcoach.org | [email protected] © & TM 2018 American Swimming Coaches Association. AMERICAN SWIMMING | 2021 EDITION ISSUE 2 3 Snorkel Train Your Breaststroke Try training breaststroke with a snorkel by Coach Cokie Lepinski, Sun City Grand Geckos You’ll find a lot of articles and videos about breaststroke timing and that’s because breast- stroke’s efficiency is intricately tied to properly timing all the individual elements. -

Men's Swimming and Diving

DIVISION I MEN’S Swimming and Diving DIVISION I MEN’S History SWIMMING and DIVING Team Results Year Champion Coach Points Runner-Up Points Host or Site Attendance 1937.......................................... Michigan Matt Mann 75 Ohio St. 39 Minnesota — 1938.......................................... Michigan Matt Mann 46 Ohio St. 45 Rutgers — 1939.......................................... Michigan Matt Mann 65 Ohio St. 58 Michigan — 1940.......................................... Michigan Matt Mann 45 Yale 42 Yale — 1941.......................................... Michigan Matt Mann 61 Yale 58 Michigan St. — 1942.......................................... Yale Robert J.H. Kiphuth 71 Michigan 39 Harvard — 1943.......................................... Ohio St. Mike Peppe 81 Michigan 47 Ohio St. — 1944.......................................... Yale Robert J.H. Kiphuth 39 Michigan 38 Yale — 1945.......................................... Ohio St. Mike Peppe 56 Michigan 48 Michigan — 1946.......................................... Ohio St. Mike Peppe 61 Michigan 37 Yale — 1947.......................................... Ohio St. Mike Peppe 66 Michigan 39 Washington — 1948.......................................... Michigan Matt Mann 44 Ohio St. 41 Michigan — 1949.......................................... Ohio St. Mike Peppe 49 Iowa 35 North Carolina — 1950.......................................... Ohio St. Mike Peppe 64 Yale 43 Ohio St. — 1951.......................................... Yale Robert J.H. Kiphuth 81 Michigan St. 60 Texas — 1952......................................... -

Florida Swimming & Diving

FLORIDA SWIMMING & DIVING 2015-16 MEDIA SUPPLEMENT FLORIDA SWIMMING & DIVING 2015-16 MEDIA SUPPLEMENT 2015-16 SCHEDULE Date Meet Competition Site Time (ET) 2015 Fri.-Sun. Sep. 18-20 All Florida Invitational Gainesville, FL All Day Thu. Oct. 8 Vanderbilt (Women Only - No Divers)* Nashville, TN 7 p.m. Sat. Oct. 10 Minnesota Minneapolis, MN 10 a.m. Fri-Sat. Oct. 16-17 Texas/Indiana Austin, TX 7 p.m. Fri (50 LCM) / Sat (25 SCY) Fri. Oct. 30 Georgia (50 LCM)* Gainesville, FL 11 a.m. Fri. Nov. 6 South Carolina* Gainesville, FL 2 p.m. Fri-Sun. Nov. 20-22 Buckeye Invitational Columbus, OH All Day Thu-Sat. Dec. 3-5 USA Swimming Nationals (50 LCM) Federal Way, WA All Day Tue-Sun. Dec. 15-20 USA Diving Nationals Indianapolis, IN All Day 2016 Sat. Jan. 2 FSU Gainesville, FL 2 p.m. Sat. Jan. 23 Auburn (50 LCM)* Gainesville, FL 11 a.m. Sat. Jan. 30 Tennessee* Knoxville, TN 10 a.m. Tue-Sat. Feb. 16-20 SEC Championships Columbia, MO All Day Fri-Sun. Feb 26-28 Florida Invitational (Last Chance) Gainesville, FL All Day Mon-Wed. March 7-9 NCAA Diving Zones Atlanta, GA All Day Thu-Sat. March 16-19 Women’s NCAA Championships Atlanta, GA All Day Thu-Sat. March 23-26 Men’s NCAA Championships Atlanta, GA All Day Key: SCY - Standard Course Yards, LCM - Long Course Meters, * - Denotes SEC events 1 FLORIDA SWIMMING & DIVING 2015-16 MEDIA SUPPLEMENT CONTENTS / QUICK facts Schedule ......................................1 Elisavet Panti ..........................33 Gator Men’s Bios – Freshmen ..................