Implicit Memory, Constructive Memory, and Imagining the Future: a Career Perspective

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Cognitive Interview for Witnesses with High-Functioning Autism

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Bath Research Portal Citation for published version: Maras, KL & Bowler, DM 2010, 'The cognitive interview for eyewitnesses with autism spectrum disorder', Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, vol. 40, no. 11, pp. 1350-1360. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-010- 0997-8 DOI: 10.1007/s10803-010-0997-8 Publication date: 2010 Document Version Peer reviewed version Link to publication The final publication is available at link.springer.com University of Bath General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 13. May. 2019 Cognitive Interview and ASD 1 The cognitive interview for witnesses with autism spectrum disorder Katie L. Maras Dermot M Bowler Autism Research Group City University Running Head: Cognitive interview and ASD 1 Cognitive Interview and ASD 2 Abstract The Cognitive Interview (CI) is one of the most widely accepted forms of interviewing techniques for eliciting the most detailed, yet accurate reports from witnesses. No research, however, has examined its effectiveness with witnesses with autism spectrum disorder (ASD). Twenty-six adults with ASD and 26 matched typical adults viewed a video of an enacted crime, and were then interviewed with either a CI, or a Structured Interview (SI) without the CI mnemonics. -

How Self-Relevant Imagination Affects Memory for Behaviour

APPLIED COGNITIVE PSYCHOLOGY Appl. Cognit. Psychol. 21: 69–86 (2007) Published online 10 July 2006 in Wiley InterScience (www.interscience.wiley.com). DOI: 10.1002/acp.1270 How Self-Relevant Imagination Affects Memory for Behaviour AYANNA K. THOMAS1*, DEBORAH E. HANNULA2 and ELIZABETH F. LOFTUS3 1Colby College, USA 2University of California, Davis, USA 3University of California, Irvine, USA SUMMARY Research has demonstrated that imagination can be used to affect behaviour and also to distort memory, yet few studies have examined whether the effects of imagination on behavioural estimates and memory are related. In two experiments, the effects of imagination on self-reported behaviour and subsequent memory for that behaviour were investigated. A comparison of behavioural estimates collected before and after imagination demonstrated that reported estimates of behaviour changed after imagination. In addition, memory for the original estimates of behaviour was also affected, suggesting that imagination may impair one’s ability to remember originally reported behaviour. Experiment 2 demonstrated that the observed changes in reported behaviour were accompanied by the largest errors in memory for originally reported behaviour when participants generate images based on self-relevant scenarios. On the other hand, memory distortion was minimized when participants read but did not imagine self-relevant scenarios. These results have direct application to clinicians and researchers who employ imagination techniques as behavioural modifiers, and suggest that techniques that are self-relevant but do not include imagery may be a useful alternative to imagination. Copyright # 2006 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. For decades, researchers have been interested in whether imagination, or mental simulation, can influence how we plan, perform, study and behave. -

7.1 Memory Systems

Psychological Science – Chapter 7: Memory 7.1 Memory Systems • Memory is a collection of several systems that store information in different forms for differing amounts of time. • The Atkinson-Shiffrin Model o Memory is a multistage process. Information flows through a brief sensory memory store into short-term memory, where rehearsal encodes it to long-term memory for permanent storage. Memories are retrieved from long-term memory and brought into short-term storage for further processing. o The Atkinson-Shiffrin model includes three memory stores: sensory memory, short-term memory (STM), and long- term memory (LTM). o Stores retain information in memory without using it for any specific purpose. o Control processes shift information from one memory store to another. o Some information in STM goes through encoding, the process of storing information in the LTM system. o Retrieval brings information from LTM back into STM. This happens when you become aware of existing memories, such as what you did last week. • Sensory memory is a memory store that accurately holds perceptual information for a very brief amount of time. o Iconic memory is the visual form of sensory memory and is held for about one-half to one second. o Echoic memory is the auditory form of sensory memory and is held for considerably longer, but still only about five seconds. o Iconic memory can be detected in a memory experiment: the whole report and partial report conditions. In the whole report condition, researchers flash a grid of latters on a screen for a split second and participants attempt to recall as many as possible – the whole screen. -

Crashing Memory 2.0: False Memories in Adults for an Upsetting Childhood Event

UC Irvine UC Irvine Previously Published Works Title Crashing Memory 2.0: False Memories in Adults for an Upsetting Childhood Event Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/6vx8w81s Journal Applied Cognitive Psychology, 30(1) ISSN 0888-4080 Authors Patihis, L Loftus, EF Publication Date 2015 DOI 10.1002/acp.3165 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Applied Cognitive Psychology, Appl. Cognit. Psychol. 30:41–50 (2016) Published online 15 September 2015 in Wiley Online Library (wileyonlinelibrary.com) DOI: 10.1002/acp.3165 Crashing Memory 2.0: False Memories in Adults for an Upsetting Childhood Event LAWRENCE PATIHIS1* and ELIZABETH F. LOFTUS2 1University of Southern Mississippi, Hattiesburg, USA 2University of California, Irvine, USA Summary: Previous crashing memory studies have shown that adults can be led to believe they witnessed video footage of news events for which no video footage actually exists. The current study is the first to investigate adults’ tendency to report memories of viewing footage that took place when they were children: the plane crash in Pennsylvania on 11 September 2001. We found that in a computer questionnaire, 33% indicated a false memory with at least one false detail. In a more detailed face-to-face interview, only 13% of the group described a detailed false memory. Familiarity with the news story, fantasy proneness, alcohol use, and frequency of negative emotions after 9/11 were all associated with a Persistent False Memory. Participants who had received prior suggestion were more likely to later report false memories in the subsequent interview. We discuss our novel results and the importance of the paradigm. -

What Is It Like to Be Confabulating?

What is it like to be Confabulating? Sahba Besharati, Aikaterini Fotopoulou and Michael D. Kopelman Kings College London, Institute of Psychiatry, London UK Different kinds of confabulations may arise in neurological and psychiatric disorders. This chapter first offers conceptual distinctions between spontaneous and momentary (“provoked”) confabulations, as well as between these types of confabulation and other kinds of false memories. The chapter then reviews current explanatory theories, emphasizing that both neurocognitive and motivational factors account for the content of confabulations. We place particular emphasis on a general model of confabulation that considers cognitive dysfunctions in memory and executive functioning in parallel with social and emotional factors. It is argued that all these dimensions need to be taken into account for a phenomenologically rich description of confabulation. The role of the motivated content of confabulation and the subjective experience of the patient are particularly relevant in effective management and rehabilitation strategies. Finally, we discuss a case example in order to illustrate how seemingly meaningless false memories are actually meaningful if placed in the context of the patient’s own perspective and autobiographical memory. Key words: Confabulation; False memory; Motivation; Self; Rehabilitation. 1 Memory is often subject to errors of omission and commission such that recollection includes instances of forgetting, or distorting past experience. The study of pathological forms of exaggerated memory distortion has provided useful insights into the mechanisms of normal reconstructive remembering (Johnson, 1991; Kopelman, 1999; Schacter, Norman & Kotstall, 1998). An extreme form of pathological memory distortion is confabulation. Different variants of confabulation are found to arise in neurological and psychiatric disorders. -

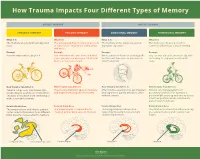

How Trauma Impacts Four Different Types of Memory

How Trauma Impacts Four Different Types of Memory EXPLICIT MEMORY IMPLICIT MEMORY SEMANTIC MEMORY EPISODIC MEMORY EMOTIONAL MEMORY PROCEDURAL MEMORY What It Is What It Is What It Is What It Is The memory of general knowledge and The autobiographical memory of an event The memory of the emotions you felt The memory of how to perform a facts. or experience – including the who, what, during an experience. common task without actively thinking and where. Example Example Example Example You remember what a bicycle is. You remember who was there and what When a wave of shame or anxiety grabs You can ride a bicycle automatically, with- street you were on when you fell off your you the next time you see your bicycle out having to stop and recall how it’s bicycle in front of a crowd. after the big fall. done. How Trauma Can Affect It How Trauma Can Affect It How Trauma Can Affect It How Trauma Can Affect It Trauma can prevent information (like Trauma can shutdown episodic memory After trauma, a person may get triggered Trauma can change patterns of words, images, sounds, etc.) from differ- and fragment the sequence of events. and experience painful emotions, often procedural memory. For example, a ent parts of the brain from combining to without context. person might tense up and unconsciously make a semantic memory. alter their posture, which could lead to pain or even numbness. Related Brain Area Related Brain Area Related Brain Area Related Brain Area The temporal lobe and inferior parietal The hippocampus is responsible for The amygdala plays a key role in The striatum is associated with producing cortex collect information from different creating and recalling episodic memory. -

Emotionally Charged Autobiographical Memories Across the Life Span: the Recall of Happy, Sad, Traumatic, and Involuntary Memories

Psychology and Aging Copyright 2002 by the American Psychological Association, Inc. 2002, Vol. 17, No. 4, 636–652 0882-7974/02/$5.00 DOI: 10.1037//0882-7974.17.4.636 Emotionally Charged Autobiographical Memories Across the Life Span: The Recall of Happy, Sad, Traumatic, and Involuntary Memories Dorthe Berntsen David C. Rubin University of Aarhus Duke University A sample of 1,241 respondents between 20 and 93 years old were asked their age in their happiest, saddest, most traumatic, most important memory, and most recent involuntary memory. For older respondents, there was a clear bump in the 20s for the most important and happiest memories. In contrast, saddest and most traumatic memories showed a monotonically decreasing retention function. Happy involuntary memories were over twice as common as unhappy ones, and only happy involuntary memories showed a bump in the 20s. Life scripts favoring positive events in young adulthood can account for the findings. Standard accounts of the bump need to be modified, for example, by repression or reduced rehearsal of negative events due to life change or social censure. Many studies have examined the distribution of autobiographi- (1885/1964) drew attention to conscious memories that arise un- cal memories across the life span. No studies have examined intendedly and treated them as one of three distinct classes of whether this distribution is different for different classes of emo- memory, but did not study them himself. In his well-known tional memories. Here, we compare the event ages of people’s textbook, Miller (1962/1974) opened his chapter on memory by most important, happiest, saddest, and most traumatic memories quoting Marcel Proust’s description of how the taste of a Made- and most recent involuntary memory to explore whether different leine cookie unintendedly brought to his mind a long-forgotten kinds of emotional memories follow similar patterns of retention. -

Obtaining Initial Accounts from Victims and Witnesses

Obtaining initial accounts from victims and witnesses A Rapid Evidence Assessment to support the development of College guidelines on obtaining initial accounts from victims and witnesses Version 1.0 Will Finn Abigail McNeill Fiona Mclean Obtaining initial accounts REA report © – College of Policing Limited (2019) This publication is licensed under the terms of the Open Government Licence v3.0 except where otherwise stated. To view this licence, visit nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open- government-licence/version/3, write to the Information Policy Team, The National Archives, Kew, London TW9 4DU or email: [email protected]. Where we have identified any third party copyright information, you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned. This publication is available at: http://whatworks.college.police.uk/Research/Pages/Published.aspx The College of Policing will provide fair access to all readers and, to support this commitment, this document can be provided in alternative formats. Send any enquiries regarding this publication, including requests for an alternative format to: [email protected]. Page 2 of 142 Version 1.0 Obtaining initial accounts REA report Contents Executive summary .............................................................................................................. 5 Introduction ......................................................................................................................... 10 Background....................................................................................................................... -

Imagination Reduces False Memories for Everyday Action Sentences: Evidence from Pragmatic Inferences

ORIGINAL RESEARCH published: 20 August 2021 doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.668899 Imagination Reduces False Memories for Everyday Action Sentences: Evidence From Pragmatic Inferences María J. Maraver *, Ana Lapa , Leonel Garcia-Marques , Paula Carneiro and Ana Raposo CICPSI, Faculdade de Psicologia, Universidade de Lisboa, Lisbon, Portugal Human memory can be unreliable, and when reading a sentence with a pragmatic implication, such as “the karate champion hit the cinder block,” people often falsely remember that the karate champion “broke” the cinder block. Yet, research has shown that encoding instructions affect the false memories we form. On the one hand, instructing participants to imagine themselves manipulating the to-be-recalled items increase false Edited by: Rui Paulo, memories (imagination inflation effect). But on the other hand, instructions to imagine Bath Spa University, United Kingdom have reduced false memories in the DRM paradigm (imagination facilitation effect). Here, Reviewed by: we explored the effect of imaginal encoding with pragmatic inferences, a way to study Marie Geurten, false memories for information about everyday actions. Across two experiments, University of Liège, Belgium Marek Nieznan´ski, we manipulated imaginal encoding through the instructions given to participants and the Cardinal Stefan Wyszyn´ski University, after-item filler task (none vs. math operations). In Experiment 1, participants were either Poland Naveen Kashyap, assigned to the encoding condition of imagine + no filler; pay attention + math; or Indian Institute of Technology memorize + math. In Experiment 2, the encoding instructions (imagine vs. memorize) and Guwahati, India the filler task (none vs. math) were compared across four separate conditions. Results *Correspondence: from the two experiments showed that imagination instructions lead to better memory, María J. -

Pervasive Autobiographical Memory Loss Encompassing Personali

Autobiographical memory unknown 1 Autobiographical memory unknown: Pervasive autobiographical memory loss encompassing personality trait knowledge in an individual with medial temporal lobe amnesia Aubrey A. Wanka,b, Anna Robertsona1, Sean C. Thayera, Mieke Verfaelliec,d, Steven Z. Rapcsaka,b,f, & Matthew D. Grillia,e,f* aDepartment of Psychology, 1503 E University Blvd., University of Arizona, Tucson, Arizona 85721, USA; bBanner Alzheimer’s Institute, 2626 E River Rd., Tucson, Arizona 85718, USA; cMemory Disorders Research Center, 150 South Huntington Ave., VA Boston Healthcare System, Boston, Massachusetts 02130, USA; dDepartment of Psychiatry, Boston University School of Medicine, 72 East Concord St. Boston, Massachusetts 02118 ; eEvelyn F. McKnight Brain Institute, 1503 E University Blvd., University of Arizona, Tucson, Arizona, 85721, USA; fDepartment of Neurology, 1501 N Campbell Ave., University of Arizona, Tucson, Arizona, 85724, USA. 1Anna Robertson is now at the University of Colorado Colorado Springs Psychology Department, 1420 Austin Bluffs Pkwy., Colorado Springs, Colorado 80918, USA Email addresses: [email protected], [email protected], [email protected], [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] Corresponding Authors: Matthew D. Grilli; Aubrey A. Wank Email Address: [email protected]; [email protected] Postal Address: 1503 E University Blvd., Tucson, Arizona 85721 Autobiographical memory unknown 2 Abstract Autobiographical memory consists of distinct memory types varying from highly abstract to episodic. Self trait knowledge, which is considered one of the more abstract types of autobiographical memory, is thought to rely on regions of the autobiographical memory neural network implicated in schema representation, including the ventromedial prefrontal cortex, and critically, not the medial temporal lobes. -

Development of Strategies for Recall and Recognition

Developmental Psvchology 1976, Vol. 12, No'. 5. 406-410 Development of Strategies for Recall and Recognition BARBARA TVERSKY AND EVELYN TEIFFER Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Jerusalem, Israel Kindergartners, third graders, and fifth graders viewed 30 pictures of familiar objects, and then their free recall of the object names and their recognition of the original pictures were tested. The recognition test included pairing each picture with another similar picture of the same object. Half the subjects in each age-group were prepared for recall with a strategy known to improve it in adults, and half were prepared for recognition with a strategy known to improve recognition in adults. Children encoded the stimuli differentially in accordance with the expected mem- ory task and retrieved different stored information for each task. Both free recall and picture recognition memory improved with age. The recall strategy improved free recall performance at all ages, but the recognition strategy improved recogni- tion performance only at the oldest age tested. Investigators of both children's and ing pictorial comparison (Tversky, 1973a). adults' memory have found different Finally, there is evidence that the cognitive strategies beneficial for different memory skills underlying various strategies develop tasks (e.g., Flavell, 1970; Paivio, 1971). at different ages. Rohwer (1970) has argued Strategies are ways of encoding or repre- that children are unable to utilize imaginal senting material to facilitate later retrieval. codes effectively until they are efficient at For instance, Paivio and Csapo (1969) found verbal encoding; presumably the verbal that whereas verbal codes are particularly code allows effective access or retrieval of effective in sequential memory tasks, imagi- the image. -

The Neuroscience of Memory Development: Implications for Adults Recalling Childhood Experiences in the Courtroom

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by City Research Online Howe, M. L. (2013). Memory development: implications for adults recalling childhood experiences in the courtroom. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 14(12), pp. 869-876. doi: 10.1038/nrn3627 City Research Online Original citation: Howe, M. L. (2013). Memory development: implications for adults recalling childhood experiences in the courtroom. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 14(12), pp. 869-876. doi: 10.1038/nrn3627 Permanent City Research Online URL: http://openaccess.city.ac.uk/4186/ Copyright & reuse City University London has developed City Research Online so that its users may access the research outputs of City University London's staff. Copyright © and Moral Rights for this paper are retained by the individual author(s) and/ or other copyright holders. All material in City Research Online is checked for eligibility for copyright before being made available in the live archive. URLs from City Research Online may be freely distributed and linked to from other web pages. Versions of research The version in City Research Online may differ from the final published version. Users are advised to check the Permanent City Research Online URL above for the status of the paper. Enquiries If you have any enquiries about any aspect of City Research Online, or if you wish to make contact with the author(s) of this paper, please email the team at [email protected]. 1 The Neuroscience of Memory Development: Implications for Adults Recalling Childhood Experiences in the Courtroom Mark L. Howe1 1Department of Psychology City University London Northampton Square London EC1V 0HB UK [email protected] IN PRESS: Nature Reviews Neuroscience Preface Adults frequently provide compelling, detailed accounts of early childhood experiences in the courtroom.