Branding Camden

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Joys of Advertisements Istorians and Others Who Study Suschitzky’S Bookshop Libris at 38 Boundary in 1968

VOLUME 15 NO.3 MARCH 2015 journal The Association of Jewish Refugees The joys of advertisements istorians and others who study Suschitzky’s bookshop Libris at 38 Boundary in 1968. Its second branch, just off Finchley patterns of consumption have long Road, a mecca for scholars and connoisseurs Road facing the side of what is now Waitrose been aware of the importance of of German books. Well known in its time was John Barnes, opened in 1956 and survived Hadvertisements as rich sources of material; the Blue Danube Club at 153 Finchley Road, into the 21st century. Gideon Reuveni of the Centre for German- where Peter Herz directed Continental-style Refugee businesses in this part of London Jewish Studies at the University of Sussex, for reviews until he returned to his native Vienna catered to their clients’ needs across the example, has published fascinating work on in 1953; the Blue Danube Club was itself board of everyday life. In the sphere of office the Jews of Germany as consumers in the pre- an offshoot of another Kleinkunstbühne, the equipment, A. Breuer of 43 Buckland Crescent Hitler era. As I have myself learnt a great deal small-stage cabaret theatre Das Laterndl (The specialised in the repair and maintenance of about the community of Jewish refugees from Lantern), which had been set up at 69 Eton typewriters, while Ernst Rosenthal of 92 Eton Nazism in Britain from the ads in the back Avenue by the wartime Austrian Centre. Place, Eton College Road, offered ‘photocopies issues of AJR Information, I was intrigued by The distinctively Continental atmosphere in the middle of Hampstead’. -

Phil Cohen, Reading Room Only: Memoir of a Radical Bibliophile And

Phil Cohen, Reading Room Only: Memoir of a Radical Bibliophile, hardback, 274 pages, Nottingham: Five Leaves, 2013. ISBN: 978-1907869785; £14.99. and Sophie Parkin, The Colony Room Club: A History of Bohemian Soho, 1948-2006, hardback, 265 pages, London: Palmtree Publishers, 2012. ISBN: 978-0957435407; £35. Reviewed by James Heartfield (Freelance, UK) The Literary London Journal, Volume 12 Number 1–2 (Spring/Autumn 2015) Bloomsbury and Soho in the nineteenth century were places where political refugees lived, though the Germans preferred Bloomsbury, just to the north, on the grounds that the Parisians of Soho were all drunks and womanisers. Phil Cohen is a long-standing activist and now academic, who has written his memoir of radical Bloomsbury, while writer and club manager Sophie Parkin’s history of drinking clubs takes Soho as its epicentre, and in particular the Colony Club on Dean Street. Phil Cohen was sent to St Paul’s School and later Oxford, but his attention was taken up by the London of Somerstown and Bloomsbury. As a youth worker, he wandered through the radical 1960s, being involved in various movements of the Fluxus and Situationist art scene that he met in bookshops like Better Books, India, and later Gay’s the Word, and working for a while as an assistant to the surrealist John Latham. He participated in the radical psychoanalytic movement led by R. D. Laing, paying for his treatment with more youth work, and then took part in the Dialectic of Liberation conference with Black Power’s Stokely Carmichael, New Leftist Herbert Marcuse and Beat poet Allen Ginsberg at the Roundhouse in 1967. -

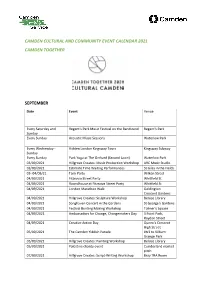

Camden Cultural and Community Event Calendar 2021 Camden Together

CAMDEN CULTURAL AND COMMUNITY EVENT CALENDAR 2021 CAMDEN TOGETHER SEPTEMBER Date Event Venue Every Saturday and Regent's Park Music Festival on the Bandstand Regent's Park Sunday Every Sunday Acoustic Music Sessions Waterlow Park Every Wednesday - Hidden London Kingsway Tours Kingsway Subway Sunday Every Sunday Park Yoga at The Orchard (Second Lawn) Waterlow Park 03/09/2021 Hillgrove Creates: Music Production Workshop ARC Music Studio 03/09/2021 Estimate Time Waiting Performances St Giles in the Fields 03- 04/09/21 Tank Party Wilken Street 04/09/2021 Fitzrovia Street Party Whitfield St 04/09/2021 Roundhouse at Fitzroiva Street Party Whitfield St 04/09/2021 London Marathon Walk Goldington Crescent Gardens 04/09/2021 Hillgrove Creates: Sculpture Workshop Belsize Library 04/09/2021 Songhaven Concert in the Gardens St George's Gardens 04/09/2021 Festival Bunting Making Workshop Tolmer's Square 04/09/2021 Ambassadors for Change, Changemakers Day 3 Point Park, Raydon Street 04/09/2021 Creative Action Day Queen's Crescent High Street 05/09/2021 The Camden Yiddish Parade JW3 to Kilburn Grange Park 05/09/2021 Hillgrove Creates: Painting Workshop Belsize Library 05/09/2021 Palestine charity event Cumberland market pitch 07/09/2021 Hillgrove Creates: Script-Writing Workshop Bray TRA Room 07/09/2021 Hillgrove Creates: Music Production Workshop ARC Music Studio 08/09/2021 Hillgrove Creates: Music Production Workshop ARC Music Studio 09/09/2021 Hillgrove Creates: Theatre Performance Belsize Library Workshop 09/09/2021 Hillgrove Creates: Music Production -

Roundhouse Access Guide 1. Introduction 2. Contact Details 3

Roundhouse Access Guide 1. Introduction 2. Contact Details 3. Venue Description 4. Bookable Access Facilities 5. How to apply 6. Travel Guide 7.1 By Tube 7.2 By Overground 7.3 By Bus 7.4 By Coach 7.5 By CarArrival Guide 7. Toilets 8. Customers with Medical Requirements 9. Access to Performance 9.1 Facilities for Deaf and Hard of Hearing Patrons 9.2 Facilities for Blind or Vision-Impaired Visitors 9.3 Venue Accessibility for Wheelchair Users 9.4 Relaxed Performances at the Roundhouse 10. Assistance Dogs 11. Strobe Lighting ///////////////////////////////////////////////// 1. Introduction We’re committed to making all aspects of your visit to the Roundhouse enjoyable, universally welcoming and physically accessible and are proud to have been awarded a Gold Standard Award from Attitude is Everything, recognising our on-going commitment to provide the best possible experience for deaf and disabled visitors ///////////////////////////// 2. Contact Details To discuss any access-related enquiries, please don’t hesitate to contact us: [email protected] www.roundhouse.org.uk 0300 6789 222, Option 3 (Roundhouse Access Enquiries and Accessible Ticket Purchasing) Roundhouse, Chalk Farm Road, London, NW1 8EH We will endeavor to respond to your enquiries as soon as possible. Generally speaking, this will be within 24 hours, though postal responses and requests received outside workings hours (weekends and holidays) may take a little longer. //////////////////////////////////// 3. Venue Description The Roundhouse has step free (lift) access to Accessible Toilets, Bars and Performance Spaces on all levels as well as level access to the Box Office, MADE Bar and Kitchen and Paul Hamlyn Roundhouse Studios on Level 0. -

Restaurants British French Italian Greek

11 6 RESTAURANTS BRITISH Freud 1. ODETTE’S Museum 130 Regents Park Road NW1 8XL Tel. 020 7586 8569 FRENCH TOP LOCAL ATTRACTIONS 2. BRADLEYS 25 Winchester Road 9 NW3 3NR Tel. 020 7722 3457 ENTERTAINMENT & SPORTS 3. L’ABSINTHE VENUES Hampstead Chalk 40 Chalcot Road Theatre Farm Roundhouse NW1 8LS Tel. 020 7843 4848 Regent’s Park Open Air Theatre Swiss ITALIAN Roundhouse 19 Camden CoƩage 18 4. VILLA BIANCA Lord's Cricket Ground 2 Market Jason’sJa Trip 1 Perrin’s Court, Hampstead //London NW3 1QS Tel. 020 7435 3131 Hampstead Theatre 5. J PIZZERIA AND CUCINA 17 WWaterbus 10 7 148 Regents Park Road PARKS & OUTDOOR ACTIVITIES 13 NW1 8XN Tel. 020 7586 9100 5 6. ARTIGIANO Regent's Park 12A Belsize Terrace Primrose Hill South 14 1 NW3 4AX Tel. 020 7794 4288 Primrose 16 15 Camden GREEK ZSL London Zoo Hampstead Hill Lock Camden 3 Town 7. LEMONIA Jason’s Trip - Canal Tours 89 Regents Park Road London Waterbus Company - Boat Trips NW1 8UY Tel. 020 7586 7454 CHINESE 8. ROYAL CHINA CLUB SHOPS & MARKETS 40-42 Baker Street Camden Market W1U 7AJ Tel. 020 7486 3898 9. CHINA GARDEN Camden Lock 5-6 New College Parade NW3 5EP Tel. 020 7722 9552 MUSEUMS & LANDMARKS The Jewish MALAYSIAN Museum Madame Tussauds 10. SINGAPORE GARDEN ZSL London 83 Fairfax Road Freud Museum Zoo NW6 4DY Tel. 020 7328 5314 The Jewish Museum Mornington INDIAN Crescent 11. HAZARA Abbey Road Studios & Crossing St. John’s 44 Belsize Lane Wood NW3 5AR Tel. 020 7433 1147 STEAKHOUSE FOR MORE ATTRACTIONS, 12. -

C4,700 Sq Ft 5Th Floor Office to Let Building Specification

C4,700 SQ FT 5TH FLOOR OFFICE TO LET BUILDING The Roundhouse (212 Regent’s Park Road, NW1) is an award winning, contemporary, design led building constructed from upcycled shipping containers. An additional storey is being installed. London Planning Awards 2015/2016 BEST NEW PLACE TO WORK New London Awards 2016 Office Buildings WINNER SPECIFICATION • Bike racks • Commissionaire • Passenger lift • Showers • Shell and core 4th floor fit out FLOORPLAN Balcony WC Kitchenette Lift WC Balcony View over The Roundhouse into The City LOCATION KENTISH TOWN WEST The property is located on Regent’s Park Road and is a one Kentish minute walk from Chalk Farm Town Underground station. Nearby stations include Camden Road CHALK FARM Overground, Kentish Town West Overground, Camden Town Underground and Mornington CAMDEN ROAD Crescent Underground. The Camden property is a short walk from Market Camden Market. Primrose Hill CAMDEN Regent’s Terms: Upon application Canal EPC: A(17) King’s Cross MORNINGTON CRESENT Regent’s Park KING’S CROSS Hannah Buxton Mark Gilbart-Smith 020 7075 2858 020 7409 5925 ST PANCRAS EUSTON [email protected] [email protected] INTERNATIONAL Important Notice: Savills and their clients give notice that: 1. They are not authorised to make or give any representations or warranties in relation to the property either here or elsewhere, either on their own behalf or on behalf of their client or otherwise They assume no responsibility for any statement that may be made in these particulars. These particulars do not WARREN STREET form part of any offer or contract and must not be relied upon as statements or representations of fact. -

Roundhouse Events

ROUNDHOUSE EVENTS EVENT OPPORTUNITIES IN AN ICONIC VENUE E:E: [email protected] [email protected] T: 020 7424 6771 T: 020 7424 6771 1 WHYHIRE THE ROUNDHOUSE? From Victorian beginnings as a steam-engine repair shed, to legendary cultural venue, the Roundhouse is steeped in history. Having hosted performances from Jimi Hendrix, The Doors and Pink Floyd during the 60s and 70s, the Roundhouse re-opened in 2006 following a £30m refurbishment. Performances from Britney Spears, Radiohead, Pharrell Williams and The Chemical Brothers have re-established the Roundhouse as one of London’s most iconic music venues and performance spaces. We’re available for private and corporate hire offering over 2500sqm of event space. Whether you are planning a dinner, drinks reception or awards ceremony the Roundhouse is the perfect venue to create the ultimate event. WE’RE A BIT “STUNNING − THE PERFECT BACKDROP FOR HOSPITALITY.” SPECIAL ITV There’s nothing quite like an event at the Roundhouse. Our clients enjoy... A beautiful building Explore a Grade 2 listed building, where original features sit alongside modern glass and concrete. A space where history is made Stand on the same stage that once played host to David Bowie, the Rolling Stones and Andy Warhol. A creative playground Go wild on the blank canvas our Main Space provides and make the most of our incredible lighting and sound packages. A helping hand Our attentive team of event specialists will work with you to realise your vision for your event. VENUE HIRE One of the most stunning and architecturally astounding venues in London, the Main Space is the beating heart of the Roundhouse. -

Darcus Howe: a Political Biography

Bunce, Robin, and Paul Field. "‘Dabbling with Revolution’: Black Power Comes to Britain." Darcus Howe: A Political Biography. London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2014. 27–42. Bloomsbury Collections. Web. 1 Oct. 2021. <http://dx.doi.org/10.5040/9781472544407.ch-002>. Downloaded from Bloomsbury Collections, www.bloomsburycollections.com, 1 October 2021, 10:59 UTC. Copyright © Robin Bunce and Paul Field 2014. You may share this work for non-commercial purposes only, provided you give attribution to the copyright holder and the publisher, and provide a link to the Creative Commons licence. 2 ‘ Dabbling with Revolution ’ : Black Power Comes to Britain Th e Dialectics of Liberation conference of July 1967 brought the 1960s ’ counterculture to the heart of London. Th e 2-week conference, convened by R. D. Laing and leading fi gures in the anti-psychiatry movement, featured contributions from Beat Generation writers William Burroughs and Allen Ginsberg; Emmett Grogan, founder of the San Francisco anarchist movement Th e Diggers; and the Frankfurt School neo-Marxist, Herbert Marcuse (Cooper 1968: 9). Th e conference practised the countercultural values that it preached, spontaneously transforming the Roundhouse and Camden ’ s pubs and bars into informal collegiums, the founding event of the anti-university of London (Ibid., 11). Black Power, a movement that had emerged at the cutting edge of the American Civil Rights struggle the year before, had several representatives at the conference. Th e headline black radical and the most controversial speaker by far was Howe ’ s fellow Trinidadian and childhood friend, Stokely Carmichael, now the harbinger of the Black Power revolution. Th e British press responded to his visit by branding him ‘ an evil campaigner of hate ’ and ‘ the most eff ective preacher of racial hatred at large today ’ (Humphry and Tindall 1977: 63). -

Diversity and Integration How Young People at the Roundhouse Shape

Diversity and integration How young people at the Roundhouse shape each other’s experience nef is an independent think-and-do tank that inspires and demonstrates real economic well-being. We aim to improve quality of life by promoting innovative solutions that challenge mainstream thinking on economic, environmental and social issues. We work in partnership and put people and the planet first. nef (the new economics foundation) is a registered charity founded in 1986 by the leaders of The Other Economic Summit (TOES), which forced issues such as international debt onto the agenda of the G8 summit meetings. It has taken a lead in helping establish new coalitions and organisations such as the Jubilee 2000 debt campaign; the Ethical Trading Initiative; the UK Social Investment Forum; and new ways to measure social and economic well-being. Contents Executive summary 1 Introduction 3 Understanding diversity 6 Young people’s journeys through open access programmes 15 Quantifying progress 18 Longer term outcomes for young people 20 Implications for the Roundhouse 21 Conclusion: the value added of social integration through open access programmes 23 Appendices: 1. Data collection tools 24 2. Quantitative results from young people’s survey 30 3. Quote Bank 32 Executive summary Creative programmes that bring people together from diverse backgrounds benefit participants, the arts, and society at large. At the Roundhouse, a London-based arts organisation, creative opportunities for young people are acting as social levellers and enriching the experiences of the young people they engage. The Roundhouse is an arts organisation and performance venue which offers 11- 25 year olds opportunities to participate in projects, performances or engage in a range of volunteering or work-related activities in addition to independent hires of studio spaces. -

CAMDEN LOCK QUARTER Morrisons, Chalk Farm Road, Camden, NW1 8AA

CAMDEN LOCK QUARTER Morrisons, Chalk Farm Road, Camden, NW1 8AA A SIGNIFICANT CENTRAL LONDON DEVELOPMENT PROMOTION OPPORTUNITY Overview OVERVIEW • A unique Central London Planning Promotion opportunity • Substantial Freehold and Long Leasehold site extending to circa. 3.2 Hectares (circa. 8 Acres) • Located within the heart of Camden Town • A potential wholesale redevelopment site with opportunity to maximise site bulk and massing • Suitable for a range of mixed uses, including Residential and Retail, subject to gaining the necessary consents • An opportunity to work alongside one of Britain’s most established supermarket brands, Wm Morrison Supermarkets, to promote the site and unlock significant value. CAMDEN LOCK IS SITUATED WITHIN THE CENTRAL LONDON BOROUGH OF CAMDEN, LOCATED APPROXIMATELY TWO MILES TO THE NORTH OF LONDON’S WEST END LOCATION Location Camden Town is a vibrant part of London and is globally renowned for its markets, independent fashion, music and entertainment venues. It is home MILLIONS OF VISITORS ARE to a range of businesses, small and large, notably in the media, cultural and creative sectors attracted by its unique atmosphere. DRAWN TO CAMDEN EACH Camden is considered to be one of the major creative media and advertising YEAR FOR ITS THRIVING hubs within London. It has a strong business reputation and is a magnet to software consultancies, advertising firms and publishing houses. It is also MARKETS AND FAMOUS considered a key linchpin in the Soho – Clerkenwell media triangle. ENTERTAINMENT VENUES. Approximately 30,000 full time students live in the Borough of Camden, attracted by the large number of colleges and universities within close Unlike shopping areas such as Oxford Street and Regent Street which proximity. -

CAMDEN STREET NAMES and Their Origins

CAMDEN STREET NAMES and their origins © David A. Hayes and Camden History Society, 2020 Introduction Listed alphabetically are In 1853, in London as a whole, there were o all present-day street names in, or partly 25 Albert Streets, 25 Victoria, 37 King, 27 Queen, within, the London Borough of Camden 22 Princes, 17 Duke, 34 York and 23 Gloucester (created in 1965); Streets; not to mention the countless similarly named Places, Roads, Squares, Terraces, Lanes, o abolished names of streets, terraces, Walks, Courts, Alleys, Mews, Yards, Rents, Rows, alleyways, courts, yards and mews, which Gardens and Buildings. have existed since c.1800 in the former boroughs of Hampstead, Holborn and St Encouraged by the General Post Office, a street Pancras (formed in 1900) or the civil renaming scheme was started in 1857 by the parishes they replaced; newly-formed Metropolitan Board of Works o some named footpaths. (MBW), and administered by its ‘Street Nomenclature Office’. The project was continued Under each heading, extant street names are after 1889 under its successor body, the London itemised first, in bold face. These are followed, in County Council (LCC), with a final spate of name normal type, by names superseded through changes in 1936-39. renaming, and those of wholly vanished streets. Key to symbols used: The naming of streets → renamed as …, with the new name ← renamed from …, with the old Early street names would be chosen by the name and year of renaming if known developer or builder, or the owner of the land. Since the mid-19th century, names have required Many roads were initially lined by individually local-authority approval, initially from parish named Terraces, Rows or Places, with houses Vestries, and then from the Metropolitan Board of numbered within them. -

Roundhouse Annual Review 2012/13

TICKETS 0844 482 8008 ROUNDHOUSE WWW.ROUNDHOUSE.ORG.UK ANNUAL REVIEW 2012/13 ROUNDHOUSE CHALK FARM ROAD LONDON NW1 8EH ENERGY, ENTHUSIASM & INVENTIVENESS Christopher Satterthwaite Chairman, the Roundhouse Trust Nothing has inspired me more during my time at the Ron Arad, Anthony Gormley, Alan Bennett and Roundhouse than our work with young people and Sebastian Coe, among others. the way that work runs through everything we do. Since taking my seat around the Board table at the end From our very own Street Circus troupe performing at of 2010, I’ve been continually impressed by the energy, CircusFest, to the Broadcast Crew live-streaming bands enthusiasm and inventiveness of Roundhouse staff, from the Main Space, and 15 teenagers creating and especially in these challenging economic times. And, performing The Dark Side of Love as part of the World led by Marcus, they’ve shown that they possess the Shakespeare Festival, the participation of young people skills, experience and ambition to keep developing this is an essential element of the Roundhouse experience. wonderful organisation. Every year we work with thousands of 11–25 year-olds It only remains for me to thank everyone who, in one – many of whom have been excluded, marginalised or way or another, enables the Roundhouse to keep doing disadvantaged by society – offering them a chance to such extraordinary work and reaching out to so many discover the sheer joy of participating in the arts, find young people: Arts Council England for their continued their way back into education, gain confidence or, in funding; the many companies, trusts, foundations and some cases, truly transform their lives.